What’s required to realise meaningful change in the outcomes of critical and persistent public policy challenges?

I blogged here on the requirements for transformational changes in the public realm and development. This post will examine two less-discussed requirements - the importance of leadership, and sometimes the need for disruption. First about leadership.

Consider the following public policy challenges - improve student learning outcomes, increase agriculture productivity, change cropping patterns, acquire employability skills, improve public hygiene and sanitation, lower electricity losses, implement regulatory mandates, improve primary health care, improve nutritional levels, reduce tax harassment, improve ease of doing business, and so on. Success in all these requires painstaking and long-drawn efforts involving all the stakeholders.

There are two sets of requirements to move the needle on such complex public policy challenges. The first part is the technical part - the right set of instruments and policies. The second part is the human and institutional part - the leadership and the system capabilities.

Unfortunately, while the first part hogs all the attention, the second part is consistently glossed over. There’s something easy and very appealing about the adoption of ideas like workflow automation and technology solutions, data analytics and dashboards, outsourcing and privatisation, deregulation and process re-engineering, and so on to address complex public policy challenges.

These problems have elided solutions for a long time and are a source of continuous frustration. So anything that comes with even a small likelihood of success carries an appeal to hope. Besides, the approaches like those discussed above have a strong track record of success in the private sector. Therefore, the natural inclination to extrapolate to the public sector, notwithstanding the completely different and far more complex nature of the problems. Further, there is something technical and expertise-based about them that resonates with our norms on knowledge and politics.

It’s therefore commonplace to find systems expend all effort and attention on the technical aspects while ignoring the human and institutional aspects. In the process, the second part about leadership and state capability is taken for granted.

It’s however overlooked that leadership and state capability, and not technocratic ideas, are the binding constraints to transformational change. Given the nature of these policy problems, addressing them requires painstaking and long-term engagement. It’s necessary to conceptualise and design policies and programs, guide and monitor their execution, make necessary course correction decisions, and evaluate their outputs and outcomes. This requires a high level of commitment and good-quality leadership.

The essential requirements of good leadership in a complex context like public policy formulation and execution in a country like India are a lack of personal agenda, intrinsic motivation and a desire to improve the system, relentless focus, the willingness to listen and learn, and the ability to work as a team. Admittedly, these attributes are scarce. A succession of 3-4 such leaders over an 8-10 year period and implementing the same agenda can achieve transformational change.

A complementary requirement is capabilities within the bureaucracy for effective management of these processes and executing them with fidelity. This, in turn, depends on the robustness of the processes and the capabilities of the administering officials. These capabilities have to be developed and nurtured over time. A good bureaucrat should therefore not only pursue execution but also focus on developing system capabilities so that the agenda can be sustained even after his/her departure.

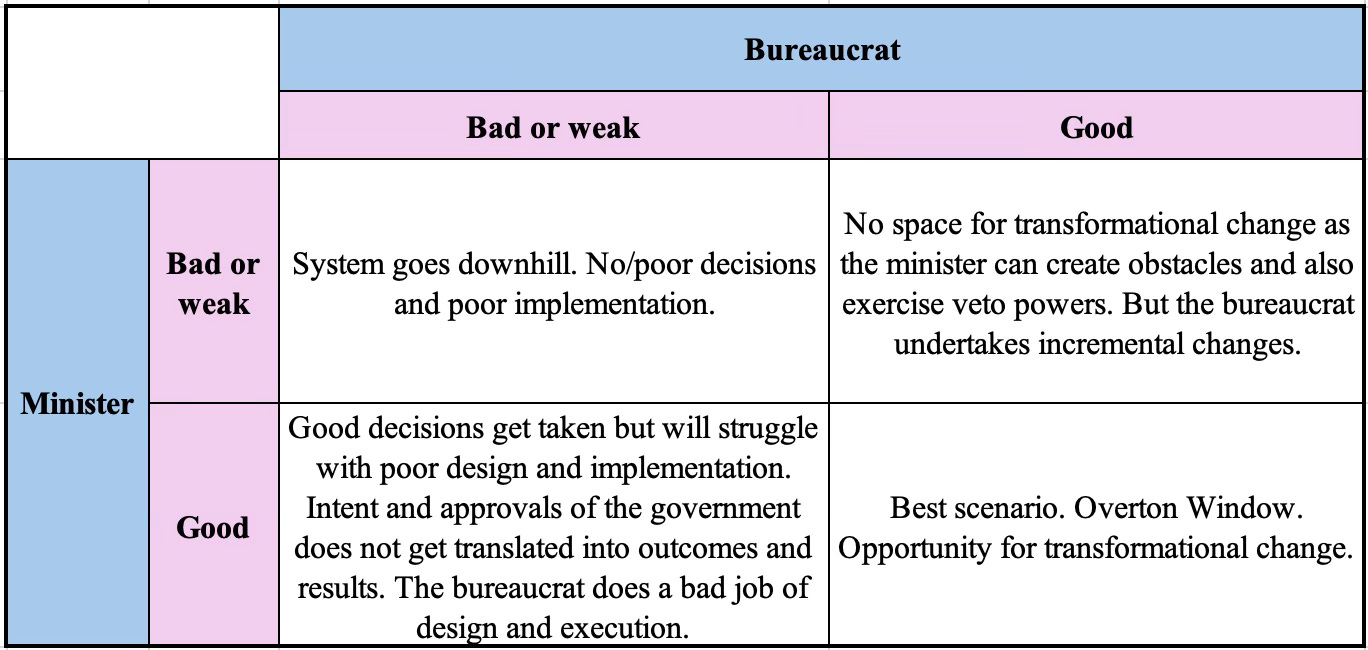

In most countries, leadership involves both the political executive and bureaucracy - the Minister and the Secretary/Head of Department. The role of the Minister would be to provide high-level political cover and guidance to push through the hard decisions. The Secretary/HoD are responsible for providing leadership in program design and execution. Neither can be effective without the other.

Now, about the other channel for transformational change, disruption.

In the case of certain kinds of policy challenges, meaningful change would require going beyond doing more of the same but better. Consider problems like improving power sector finances; reforms to subsidies like agriculture, food, and energy; changes to critical policies relating to agriculture, labour, and taxation; empowering cities and decentralisation of powers; reforms to state finances; reforms on human resource management etc.

Whichever way it’s looked, meaningful change in all these involves hard and disruptive choices with serious political consequences. They will either trigger public discontent or generate opposition among vested interests within the polity and bureaucracy or both.

For these reasons, in electorally fraught democracies such reforms have to be pushed through in the first few weeks and months of the tenure of a new government. The Overton window closes rapidly after this period.

However, apart from political commitment, such reforms require good bureaucratic leadership to ensure that the political commitment does not go to waste with poor policy design and bad execution. The promised good that comes with such reforms can be achieved only with good implementation. In its absence, we are left with a balance sheet of political ill will and a system worse off than before.

The other route for reform is to opportunistically ripen the conditions that bring the system close to collapse and make hard decisions inevitable. The power sector finances and state finances in at least some Indian states are at a stage now where the house is perhaps close to burning down.

No comments:

Post a Comment