The Government of India have recently concluded the first round of applications for accessing innovation funding through the $10.5 bn Research Development and Innovation Fund (RDIF) scheme. It has chosen the wholesale funding approach of financing alternative investment funds, development finance institutions, non-banking finance companies, and focused research organisations (FROs), which in turn give loans to or take equity in private firms and startups engaged in innovation.

What model of innovation funding generates the greatest bang for the buck in terms of achieving the primary objective of catalysing innovation?

The additionality from public funding of innovation is that it is risk-tolerant, concessional, and patient compared to commercial capital. It can be blended with commercial capital to derisk and thereby expand the envelope of investible startups. This can be done through two approaches.

One approach would be to fund startups by investing in a fund of funds (i.e., to be an LP in a startup fund). This approach would require only diligencing the fund and leaving it to diligence the individual investments. It would leave the portfolio building responsibility to the fund, albeit within the broad sectoral scope defined by the public fund. A flip side is that the fund could play it safe and avoid the riskier bets, and use the public funding to merely juice up its returns.

The other approach would be to co-invest with commercial investors. This would require significant in-house expertise in the due diligence of startups. In theory, it would ensure tight alignment with the specific policy objectives of the government and target investments to the riskier startups. But in practice, public decision-making processes are likely to detract from the objectives.

There are two possible objectives associated with public funding of innovation startups. One, to de-risk and expand the envelope of investible startups. Two, fund specific products or solutions that are considered strategically important.

In terms of these two objectives, the policy question is which one of the two approaches generates the greatest bang for the buck. An analysis of the experience of deployment of public funds through the two approaches reveals that the fund of funds approach is generally superior, except where it is required to target strategically important technologies or firms.

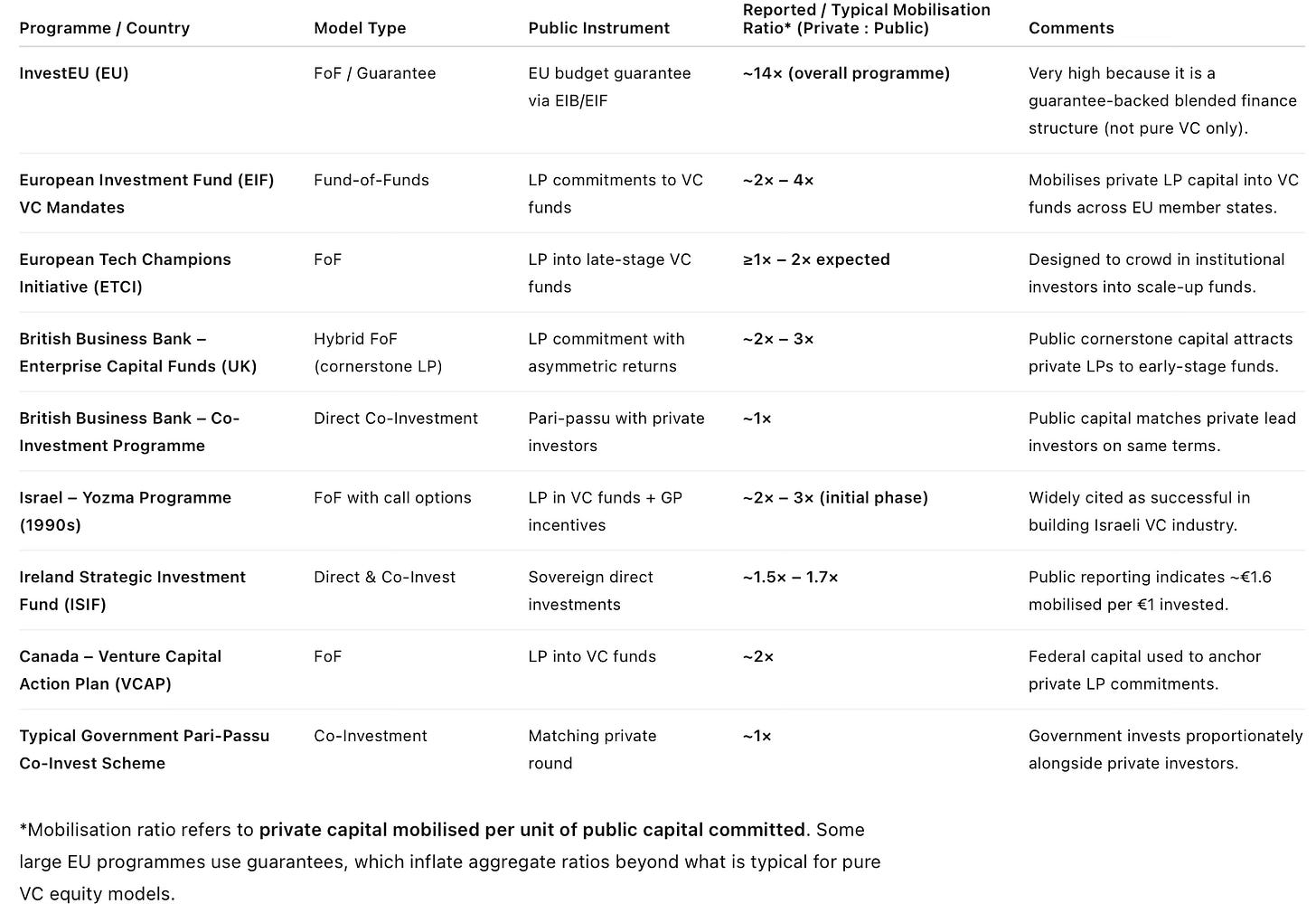

Here’s the list of a few such public funds from Europe and elsewhere, assessed in terms of their mobilisation ratios (or private capital raised per unit of public fund).

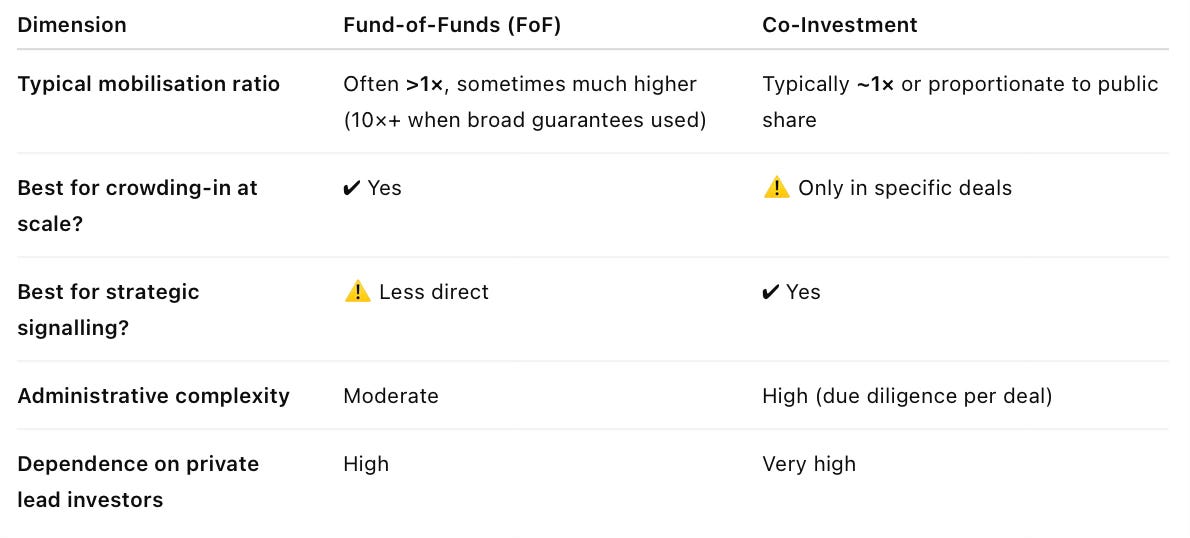

Here is a comparison of the two approaches in terms of various considerations.

Clearly, if the priority is to maximise the volume of private capital mobilisation and to catalyse the VC market, the fund-of-funds approach is superior. However, if the priority is to catalyse a few strategically important firms or technologies where private capital is reluctant, then co-investment is useful.

In emerging markets like India, where the domestic VC funding for genuine technology innovation (as opposed to imitating technologies already mainstreamed elsewhere) is negligible, there’s a risk that a fund-of-funds approach, at least for some years, could end up catalysing and unlocking the supply of venture capital finance, rather than the supply of innovative technologies. This risk will persist even with tightly prescribing the segments where the funds can invest, given the practical difficulties in monitoring, let alone policing, them. And commercial funds will have the incentive to prioritise the use of public funding to maximise the derisking of their capital instead of expanding the envelope of investible startups. This would be the long-route to catalysing innovation (or catalysing innovation primarily by catalysing risk capital funds).

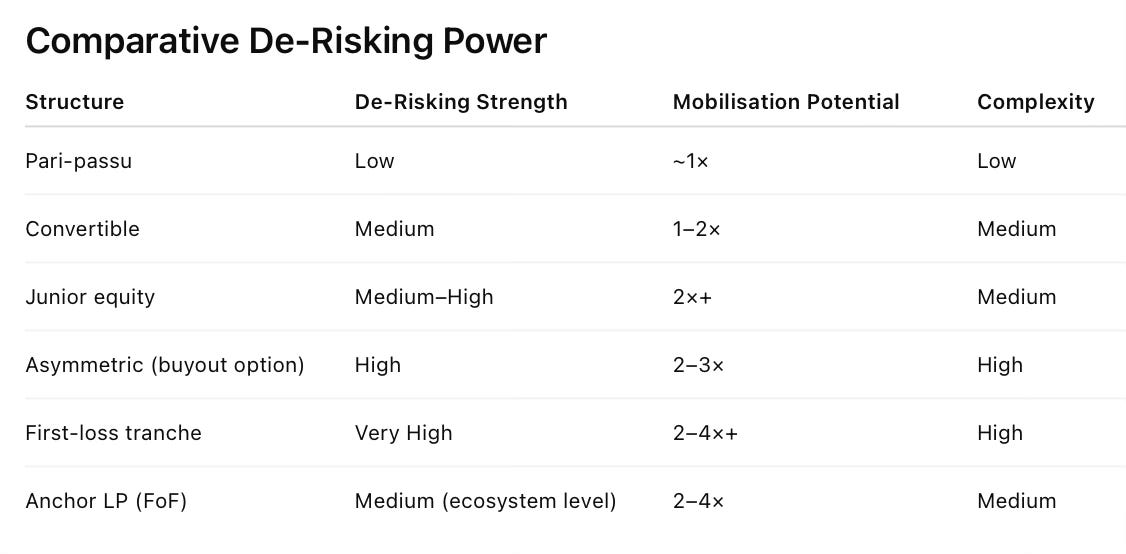

In the circumstances, it is important to consider the option of government co-investing directly in startups with private investors to provide sufficient de-risking of their investments. Such derisking can be done by public funds taking the first-loss equity buffer, offering higher liquidation preferences for private capital, capping public returns, anti-dilution warrants, offering buyout options at modest returns, equity conversion as subordinate capital or at a discount, etc. The graphic below captures the comparative de-risking effect of public capital.

The challenge with co-investment, of course, is the administration of such funds by a public entity and getting its governance right. While there are good examples of co-investment like the Israeli Yozma fund, European Innovation Council, and the British Enterprise Capital Fund, they have been exceptions to the generally adopted fund-of-funds approach.

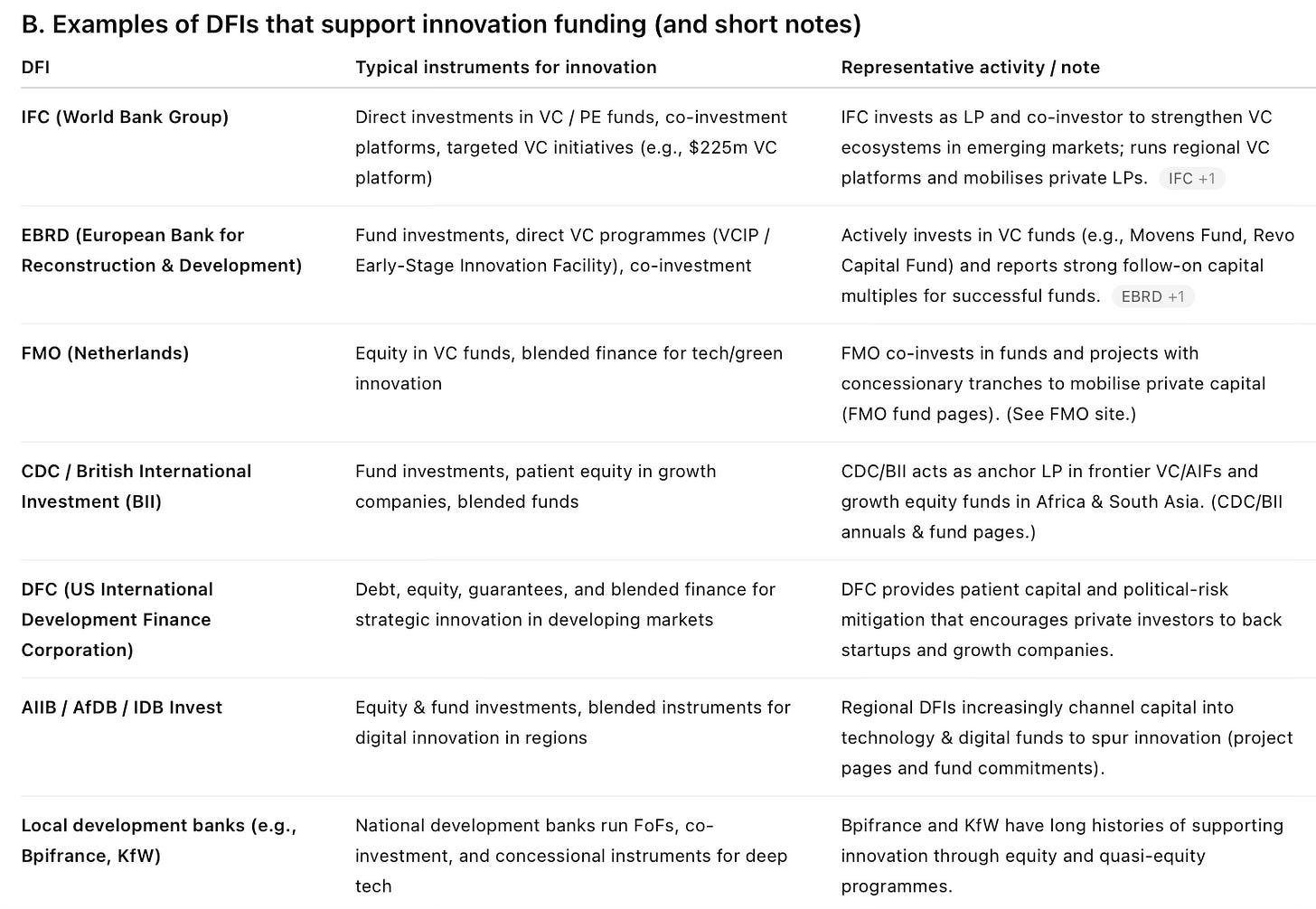

In the circumstances, DFIs are a good platform. While DFIs have traditionally focused on infrastructure financing and industrial growth, they are well placed to directly support co-investments by governments by deploying the full suite of instruments mentioned above, based on the specific nature of the investment proposal.

I am not sure how many of the above really invest in risky startup-driven innovations as opposed to investing in promising established SMEs in emerging industries.

As a note of caution, and this applies to the RDIF’s DFI window too, the experience of India’s infrastructure DFIs in actually derisking and catalysing infrastructure market segments has not been encouraging. Instead, they have most often been found chasing the market. See this and this.