There have been numerous estimates of the ultimate cost to the tax payer of the massive bailouts that have been announced by governments across the world.

NYT estimates the total funds committed for everything from the bailouts of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and those of the Wall Street firm Bear Stearns and the insurer American International Group, to the financial rescue package approved by Congress, to providing guarantees to backstop selected financial markets is a very big number indeed - $5.1 trillion, more than a third of the US economy! How much of this will be recovered and how much lost to the tax payer? How the bailout plan is administered and its details will ultimately determine the final cost to the economy.

This post had been written and got lost somewhere amidst the drafts. It is published without making changes and it captures how most of the predictions made by people like Nouriel Roubini have been proved right.

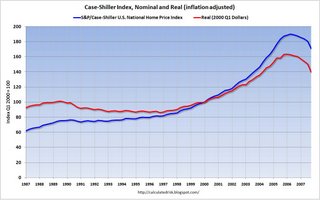

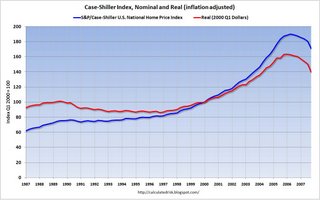

This post had been written and got lost somewhere amidst the drafts. It is published without making changes and it captures how most of the predictions made by people like Nouriel Roubini have been proved right. Calculated Risk claims that in nominal terms, the [Case-Shiller] index is off 8.9% over the last year, and 10.2% from the peak. However, in real terms, the index has declined 12.9% during the last year, and is off 14.6% from the peak. About the extent to which housing prices can fall, it writes, "If prices will eventually fall 30% in nominal terms, then we are only about 1/3 of the way there. But if the eventual decline is 30% in real terms, then we are about half way there."

Ben Bernanke estimated the sub-prime losses at just $100bn last July. On March 7, 2008, Goldman Sachs economists published an even higher estimate of mortgage-related losses, at $500bn, along with $656bn in other losses, for a total of $1,156bn. In reaching its conclusion, Goldman estimated a peak-to-trough house price fall of 25 per cent. Martin Wolf analysed that the aggregate financial sector losses amount to $1,000bn. He also claimed that this would be manageable, if painful, for an economy as big and a government as creditworthy as that of the US.

Prof Nouriel Roubini of New York University’s Stern School of Business argues that financial losses might amount to $3,000bn. Prof Roubini notes that a 10 per cent fall in house prices (relative to the peak) knocks off $2,000bn (14 per cent of gross domestic product) from household wealth. The first 10 per cent fall has already happened. What he sees as a likely 30 per cent cumulative fall would wipe out $6,000bn, 42 per cent of GDP and 10 per cent of household wealth. Already, falling prices are showing up in declining net household wealth. Prof Roubini also talks of a $5,600bn decline in the value of stocks and the possibility of additional trillions of dollars in losses on commercial property. Total losses might even equal annual GDP.

Martin Wolf argues that "the principal direct effect of such losses will be on spending, particularly residential investment and household consumption. In the third quarter of last year, personal savings were a mere 2.4 per cent of GDP, while the financial balance of the personal sector (the difference between its income and expenditure) was minus 2.1 per cent. These patterns do not make sense when asset prices are falling. But a sharp rise in household savings would ensure a deep and durable recession."

Worse, the bigger the damage to the financial sector, the more credit-fuelled personal spending is going to dry up. So what might such overall losses mean for financial intermediaries. In Prof Roubini’s 12 steps to meltdown, discussed here on February 20, 2008, he assumed that their losses on mortgages would be $300bn-$400bn, while losses on other assets (consumer debt, commercial real estate loans and so forth) would be another $600bn-$700bn, for a total of $1,000bn.The mainstream has caught up. But Prof Roubini has moved on.

In his comments on the FT’s forum, Prof Roubini suggests that, after price falls of 20 per cent from the peak, losses on mortgages could be as much as $1,000bn. With a 40 per cent fall, they could be $2,000bn. He adds another $700bn for other losses, to reach total financial sector losses of close to $3,000bn, or about 20 per cent of GDP.

So how does Prof Roubini reach these much higher figures? The difference between him and Goldman is not so much in assumptions about the house price fall: 25 per cent for Goldman Sachs and 20-40 per cent for Prof Roubini. Both also estimate that lenders would lose half of the loan value after repossession. But Goldman believes that just 20 per cent of households in negative equity would default, while Prof Roubini believes 50 per cent might do so.

For people with poor credit ratings and few assets, apart from their house, walking away does seem to make disturbingly good sense (“Jingle-mail rings alarm bells for lenders”, Financial Times, March 7). Buyers with no equity had an option to walk. Now they are exercising it. This was demented finance. Yet, so long as the economy remains reasonably robust, highly indebted people with good career prospects would surely not wish to wreck their credit rating. Nevertheless, markets are pessimistic: the prices of even AAA tranches of securitised loans are collapsing.

Suppose, then, that Prof Roubini were right. Losses of $2,000bn-$3,000bn would decapitalise the financial system. The government would have to mount a rescue. The most plausible means of doing so would be via nationalisation of all losses. While the US government could afford to raise its debt by up to 20 per cent of GDP, in order to do this, that decision would have huge ramifications. We would have more than the biggest US financial crisis since the 1930s. It would be an epochal political event.

Yet, Goldman argues that, after allowing for loan-loss provisions, the proportion of loss-making loans advanced by the non-leveraged sector and the ability to write off losses against tax, its $1,156bn comes down to $298bn. If a similar magic could be worked on the Roubini numbers, the effective losses to the leverage sector would fall to less than $750bn – huge, but more manageable.

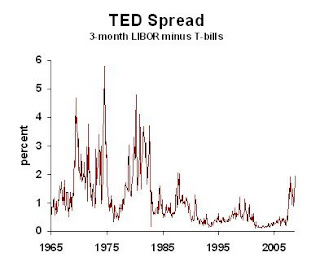

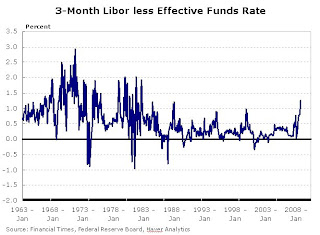

Much will depend on what happens to the economy. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of monetary policy is constrained when the worries are more about insolvency than illiquidity. Concern about credit quality is rampant, not least in the resurgent spreads on interbank lending. Monetary policy is further constrained when lower short-term interest rates fail to translate into long-term rates, partly because of worries about inflation.

Alas, worries are understandable. There are two ways of adjusting the prices of housing to incomes: allow nominal prices to fall or raise nominal incomes. The former means mass bankruptcy and a huge fiscal bail out; the latter imposes the inflation tax. In extreme circumstances inflation must be attractive. Even if it is not the Fed’s choice, it is what a reasonable outsider might fear, with obvious consequences for all asset prices.

I suspect Prof Roubini’s latest estimates are excessively pessimistic. But I am not certain this is so, given his record: just look at the vicious interaction between falling asset prices, financial stress and spending. We must pray that the Fed can clean it all up, without excessive collateral damage. Unfortunately, such prayers often go unanswered.