This post in the series on affordable housing discusses the importance of transportation investments in promoting housing affordability.

In an excellent 2014 paper, Katharina Knoll, Moritz Schularick, and Thomas Steger show that property prices remained constant in real terms for the major part of the development stages of 14 advanced economies (studied in the paper), driven in large part by transportation technologies and investments.

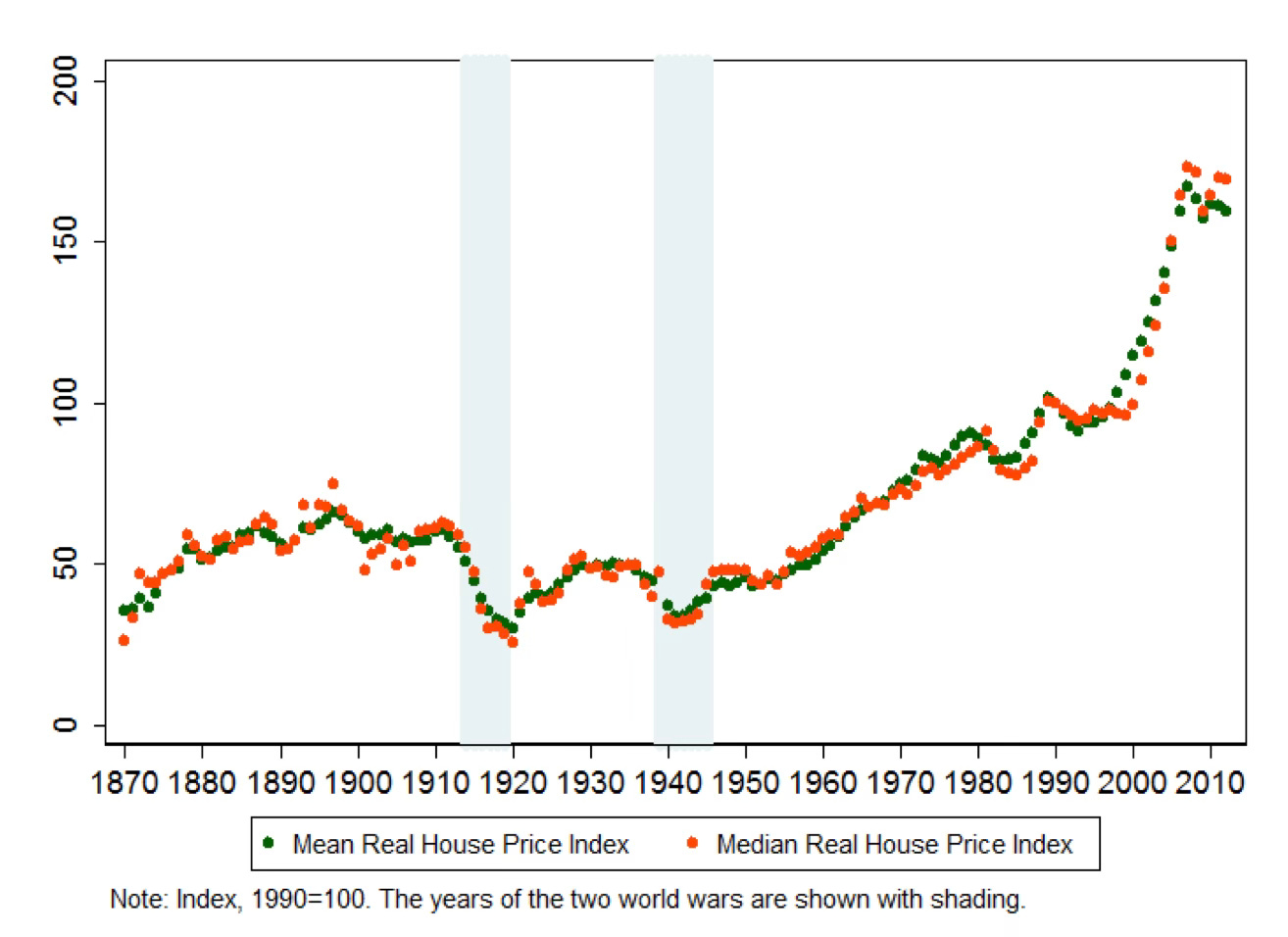

This paper presents annual house price indices for 14 advanced economies since 1870. Based on extensive data collection, we are able to show for the first time that house prices in most industrial economies stayed constant in real terms from the 19th to the mid-20th century, but rose sharply in recent decades… By the 1960s, they were, on average, not much higher than they were on the eve of World War I. They have been on a long and pronounced ascent since then. For our sample, real house prices have approximately tripled since the beginning of the 20th century, with virtually all of the increase occurring in the second half of the 20th century. We also find considerably cross-country heterogeneity. While Australia has seen the strongest, Germany has seen the weakest increase in real house prices in the long-run. Moreover, we demonstrate that urban and rural house prices have, by and large, moved together and that long-run farmland prices exhibit a similar long-run pattern…

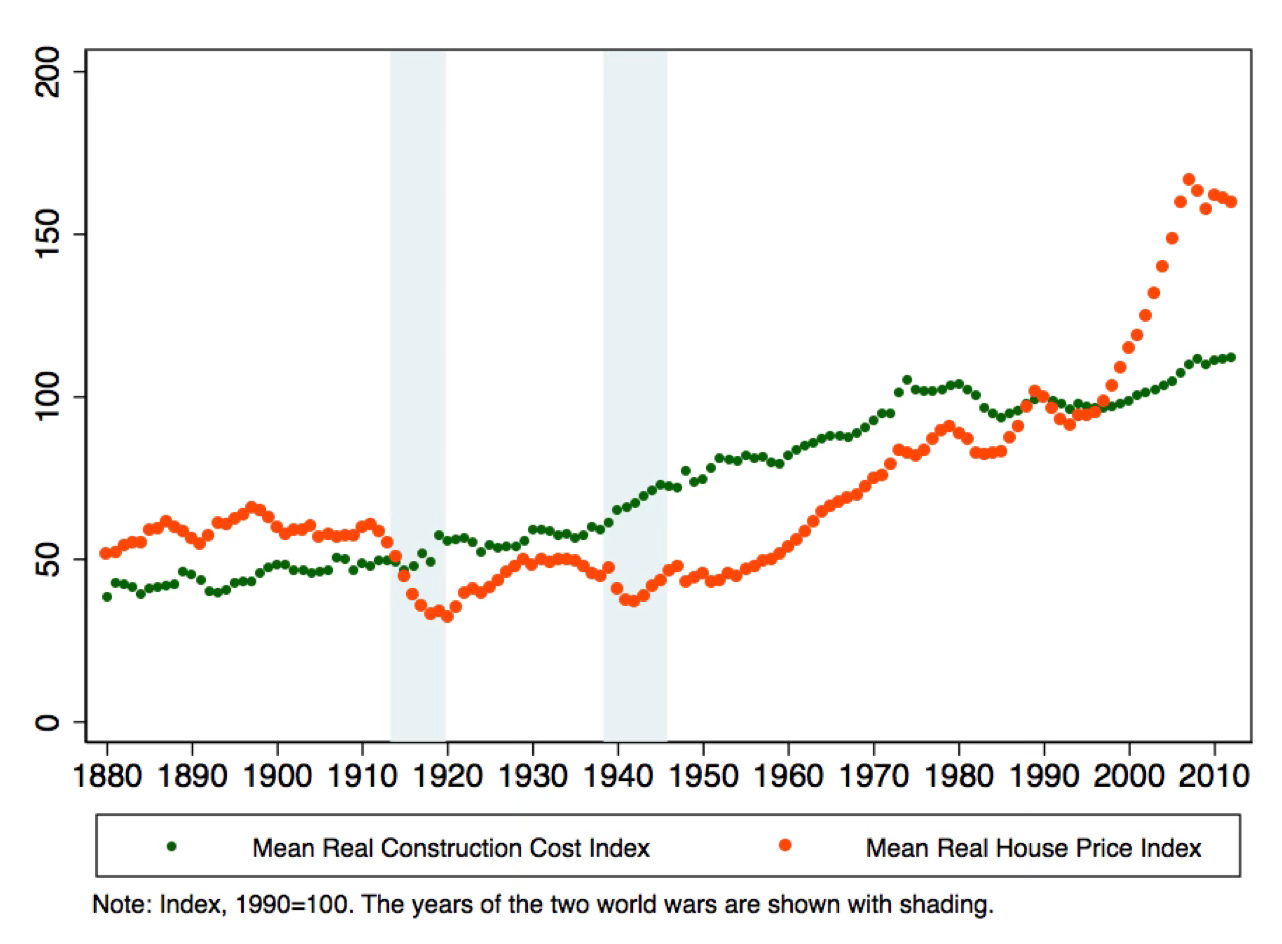

While construction costs have flat-lined in the past decades, sharp increases in residential land prices have driven up international house prices… During the past four decades, construction costs in advanced economies have remained broadly stable, while house prices surged… Our decomposition suggests that about 80 percent of the increase in house prices between 1950 and 2012 can be attributed to land prices. The pronounced increase in residential land prices in recent decades contrasts starkly with the period from the late 19th to the mid-20th century. During this period, residential land prices remained, by and large, constant in advanced economies despite substantial population and income growth…

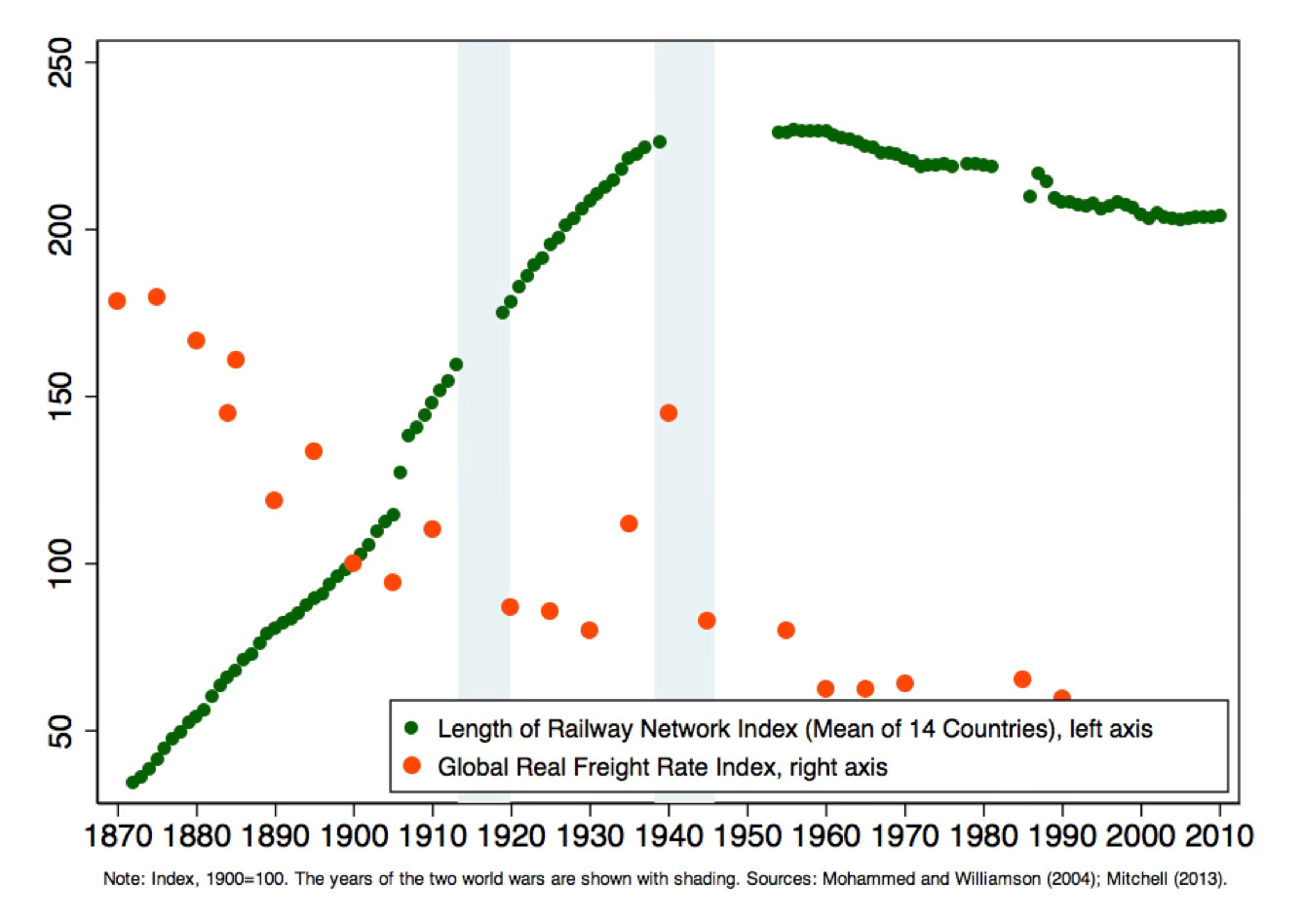

From the 19th to the early 20th century the transport revolution – mostly the construction of the railway network, but also the introduction of steam shipping and cars – led to a massive and well-documented drop in transport costs, often referred to as the transportation revolution. An important effect of the transport revolution was to substantially augment the supply of economically usable land… We show that this land-augmenting decline in transport costs subsides in the second half of the 20th century so that land increasingly became a fixed factor. At the same time, zoning regulations and other restrictions on land use also inhibited the utilisation of additional land in recent decades while rising expenditure shares for housing services added further to the rising demand for land…

Glaeser and Kohlhase calculate that the average cost of moving a ton a mile was 18.5 cents (in 2001 Dollars) in 1890 but had fallen to 2.3 cents at the beginning of the 2000s… The length of the railway network can serve as a proxy for the opening up of new territories over time. For our 14 countries, the length of the railway network peaked in the interwar period and has not grown materially since then… By 1930, essentially the entire world had been made accessible. Subsequent expansions of the transportation network through highways did not lead to a comparable fall in transportation costs… The dramatic efficiency gains in maritime transportation were also realized in the late 19th and early 20th century. The 19th century revolution in shipping rested on two developments: first, the fall of iron and steel prices that led to the introduction of metallic hulls; second, parallel advances in engine technology that led to much improved fuel efficiency Between 1870 and 1914 shipping costs fell by about 50 percent relative to the prices of commodities. By contrast, commodity-deflated real freight rates barely fell after 1950.

They offer a reinterpretation of David Ricardo’s hypothesis (made in the context of agricultural land, specifically where corn is grown) that, since land is a fixed factor, in the long run, economic growth will disproportionately benefit landlords. Further, given the unequal distribution of land, the rising land prices is likely to worsen inequality. They write,

The decline in transport costs kept the price of residential land constant until the mid-20th century. Yet the price surge in the past half-century could be an indication that Ricardo might have been right after all.

Illustrating the insights on the interaction between transportation developments and land prices, Binyamin Applebaum in the Times has an excellent article which shows how Tokyo has become a standout success in affordable housing on the back of a housing development strategy that revolves around mass transit. It has become the largest city in the world while also remaining affordable for its residents. Here’s a striking statistic.

Two full-time workers earning Tokyo’s minimum wage can comfortably afford the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in six of the city’s 23 wards. By contrast, two people working minimum-wage jobs cannot afford the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in any of the 23 counties in the New York metropolitan area.

This success comes with its costs and benefits

Maintaining an abundance of affordable housing has its downsides. Green space is scarce in Tokyo, living spaces are small by Western standards, and relentless redevelopment disrupts communities. But the benefits are profound. Those who want to live in Tokyo generally can afford to do so. There is little homelessness here. The city remains economically diverse, preserving broad access to urban amenities and opportunities. And because rent consumes a smaller share of income, people have more money for other things — or they can get by on smaller salaries — which helps to preserve the city’s vibrant fabric of small restaurants, businesses and craft workshops.

This is an important pointer to how Tokyo has managed a balancing act between urban growth and affordable housing.

From the air or from one of the city’s many observation decks, Tokyo appears as a vast sea of low- and midrise buildings laced with archipelagoes of high-rises, each island marking the location of a station along one of the city’s railroad lines.

This brilliantly captures the evolution of Tokyo’s housing landscape.

The Tokyu Railways Company developed the Den-en-toshi, or Garden City, line, which stretches southwest from the city center, in the 1950s as the backbone for a series of suburban neighborhoods of single-family homes… As Tokyo grew and demand for housing increased, the railroad has rebuilt the areas around its stations with condominium towers, shopping malls and office buildings. Around Futako Tamagawa Station, the largest of these new urban centers, Tokyu knocked down more than 100 homes to make way for more than 1,000 units in new apartment towers, as well as a new headquarters for the technology company Rakuten…

The communities around the stations have grown denser, too, with apartment buildings interspersed among single-family homes. The population served by the Den-en-toshi line has increased from 20,000 people to more than 600,000. And the railroad, which once ran two-car trains three times an hour, now runs subway-style trains every few minutes, many of which continue into central Tokyo on a subway line. “We consider ourselves as a city-shaping company,” Hirofumi Nomoto, then chief executive of Tokyu, said in a 2016 interviewafter the completion of the Futako Tamagawa redevelopment project. “In Europe, for instance, railways companies simply connect cities through their terminals. That is a pretty normal way of operating in this industry, whereas what we do is completely different: We create cities.”

In stark contrast to Tokyo, cities like New York and others have stopped investing in mass transit lines and have strict restrictions on development along existing lines. And the consequences are evident in terms of housing unaffordability.

This transit-led urban growth model has been supported by the city’s remarkably liberal zoning regulations.

In Tokyo, by contrast, there is little public or subsidized housing. Instead, the government has focused on making it easy for developers to build. A national zoning law, for example, sharply limits the ability of local governments to impede development. Instead of allowing the people who live in a neighborhood to prevent others from living there, Japan has shifted decision-making to the representatives of the entire population, allowing a better balance between the interests of current residents and of everyone who might live in that place. Small apartment buildings can be built almost anywhere, and larger structures are allowed on a vast majority of urban land. Even in areas designated for offices, homes are permitted. After Tokyo’s office market crashed in the 1990s, developers started building apartments on land they had purchased for office buildings.

Tokyo makes little effort to preserve old homes. Historic districts subject to preservation laws exist in other Japanese cities, but the nation’s largest city has none. New construction is prized. People treat homes like cars: They want the latest models. Between 2013 and 2018, new homes accounted for 86 percent of home sales in Japan, according to the most recent government data. In the United States, new homes typically account for about 15 percent of sales, according to data from the National Association of Realtors. One reason Tokyo looks forward is that little remains of the city’s past. Earthquakes, fires and American bombers destroyed much of the prewar city, and after the war, the rush to provide housing and the nation’s relative poverty produced a city that wasn’t meant to last… New buildings, and their occupants, also are more likely to survive the next earthquake… The ease of building in Tokyo means that new construction is not synonymous with luxury housing. Small workshops and factories are common…

Parks, too, are sometimes treated as unaffordable luxuries. Parks and gardens occupy just 7.5 percentof the city’s land, far below the figures for New York (27 percent) and London (33 percent). Mitake Park, once one of the few green spaces in the dense Shibuya neighborhood, is being transformed into a 26-unit apartment building. In the nearby neighborhood of Shinjuku, the government this year authorized construction of three high-rises that will eat into the Meiji Jingu Gaien, one of the city’s oldest and best-loved parks.

In another article in the Nikkei Asian Review, Benjamin Banzal and Jorge Almazan provide a nice description of Tokyo’s urban form.

After the firebombing of 1945, rebuilding was chaotic. Black markets flourished around train stations, while a severe housing shortage was often met with makeshift wooden homes on tiny plots, rather than large public housing. The government, constrained by weak institutions and scarce resources, was in no position to guide the city's recovery. When Japan's economic miracle took off in the 1950s, much of Tokyo's growth was driven by small, labour-intensive workshops embedded in residential districts. Zoning was flexible. Mixed-use, live-work arrangements were commonplace. Production chains were held together not by vertical corporate hierarchies but by horizontal social ties and local agglomeration economies. Subway expansion gradually allowed the city to grow outward, easing pressure on the center. Population density thus evened out across the metropolis. From above, Tokyo's vastness appears homogeneous, but its neighbourhoods remain distinct -- unified more by a shared set of local amenities than by architectural design.

These amenities -- sento bathhouses, mom and pop stores, small manufacturing workshops, construction and building material contractors, eateries -- were tightly interwoven into the urban fabric and often owned and operated by local inhabitants, anchoring employment in neighborhoods. This model proved both functional and socially cohesive. With little open space, residents placed planters on pavements. Festivals were organised block by block. Economic growth did not produce stark urban divides. Tokyo remained relatively egalitarian in spatial terms.

The compact neighbourhoods that emerged in post-war Japan resemble the lightly planned, dense, mixed-use localities with small plots, narrow roads, limited public spaces, and low-rise multi-tenanted housing that characterise the majority of localities across all Indian cities. They have emerged organically through development by the original small plot owners, and encompass both slums and lower-middle and middle-class housing colonies.

While in India, these colonies have largely remained stuck in time, with a slum-like quality of basic infrastructure. In contrast, Japan's provision of infrastructure and liberalised zoning regulations have allowed these colonies to become vibrant neighbourhoods that have retained their original character and social cohesion.

The foundations of what we call the "Tokyo model" include dense, low-rise neighborhoods of around 20,000 residents per square kilometer woven together by narrow streets, gradually upgraded over time. Urbanism was "emergent," that is bottom-up and responsive to local needs… Private railway conglomerates such as Tokyu, Keio and Seibu also played a central role. They captured real estate value along their commuter rail lines -- building commercial hubs around stations and housing developments further out. In turn, Tokyo's transit system became one of the most efficient in the world, and helped spread the neighbourhood model across the metropolitan region…

A mix of three phenomena around train stations added dynamism to this urban model. First, shotengaishopping streets, often covered arcades, branch off from station plazas and are filled with small, owner-run stores. Second, yokocho alleyways emerged when postwar black markets were regularised, allocating compact plots to bars and restaurants. These alleys still foster a strong sense of community. Third, zakkyobuildings -- narrow, multi-tenant towers on small lots -- stack diverse uses vertically, with their characteristic (neon) signage testifying to the vibrancy within.

Tokyo's urbanism has never been static. Over time, manufacturing gave way to services. Stricter environmental rules and broader economic shifts pushed industry out of the inner city. Height limits were relaxed, and taller apartment buildings began to rise along major thoroughfares. Since the 1980s, however, Tokyo's urban policy has increasingly tilted the balance toward top-down development. Floor-area-ratio restrictions were eased significantly. Special planning zones were introduced with looser urban restrictions. Tall, mixed-use towers -- especially near train stations -- became much easier to build, particularly since 2002… These towers often concentrate hundreds of apartments in a single building…

Unlike other countries that have incorporated tools for public participation, Tokyo's planning remains largely in the hands of powerful institutions: the central government, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and its 23 special wards all have a say in decisions and have systematically sided with developers. As public consultation is minimal, community voices are rarely heard or often overruled. Over 200 redevelopment projects have already been completed since 2002 -- mostly in central areas like Roppongi, Shibuya and Toranomon. Many more are in the pipeline, including a second Roppongi Hills. As central areas will inevitably reach saturation at some point, developers are looking further afield in search of yield.

This is a good summary of the balance Tokyo has achieved between renewal and social cohesion.

The Tokyo model deserves more recognition -- not out of nostalgia, but as a viable framework for future growth. Its buildings are constantly renewed. Its shops shift with demand. Its density supports both economic dynamism and social cohesion. It is a model built for change.

While I have quoted the trajectory of change in Tokyo’s urban form, the article itself cautions against the pace of change, which threatens the local character and social capital, replacing compact localities with homogeneous, gentrified high-rises.

This has important lessons for developing countries like India, where the largest cities are already bursting at their suburban seams, mired in traffic congestion, and housing affordability is an acute crisis, with urban growth prospects facing strong headwinds. Sample this FT long read on Bangalore.

The Tokyo example has strong relevance since Indian cities, too, are characterised by similar dense localities. Indian cities must create enabling mechanisms to allow them to shape and accommodate economic growth dynamically. It should allow, over time, pockets of high-rises to emerge so that the localities combine people from all economic classes.

This is important because the emerging landscape of India’s urban growth is that of older localities (both slums and middle-class colonies) frozen in time, increasingly congested, and with poor quality infrastructure (interspersed with pockets of affluent colonies), and suburban growth of homogeneous high-rise gated communities, interspersed with slums and squatter settlements. This is a deeply inefficient, unequal, socially dissonant, and growth-constricting form of urban development.

A fundamental insight in urban development is that, given the fixed extent of land available in any city, there are only two ways to increase supply. The first is to develop vertically by raising the Floor Area Ratios (FARs), a topic discussed extensively in this blog (also this paper). The other option is to expand outward to encompass suburbs, while simultaneously building transportation infrastructure that shrinks the suburban sprawl and lowers commute distances. Tokyo illustrates how the combination of the two can keep housing prices affordable.

Transportation has traditionally been a performative aspect of urban planning in India, confined largely to instruments like road widths, land-use, and transport infrastructure creation (roads, Bus Rapid Transit, and metro railways). Unfortunately, public policy actions have largely been a form of isomorphic mimicry by transplanting top-down technocratic institutional arrangements (like UMTA/MTA and concepts like Modal Integration and Transit Oriented Development) that have worked in the cities of mature developed economies, without any thought for their integration with the local urban planning norms and without any meaningful social and political engagement and ownership by those stakeholders of the need for such changes. Even when implemented, they have remained only in form and have had little to show as substance.

Accordingly, over the last two decades, we have seen that large transportation investments are made with limited changes to the master plan norms on land-use, FAR, and other measures to use the opportunity (presented by those investments) to shape urban growth and the future of the city. This is most egregiously manifest in the investments being made in new roads, road widenings, ring roads, BRT lines, metro-railway lines, and (now) the railway station redevelopment projects. In all these cases, there’s rarely any conscious, highest-level engagement to capitalise on the infrastructure investment’s geography-shrinking and housing supply-increasing potential by leveraging urban planning instruments.

I blogged here that instead of being stand-alone PPP projects undertaken by the Indian Railways, railway station redevelopment projects should be viewed as urban regeneration projects that lay the foundation for the future of the locality and the broader city itself. I blogged here on the need to utilise metro railway investments as an opportunity to shape urban form by densifying the well-connected localities around stations through higher FAR and mixed land use. This and this are illustrative examples of transit-oriented development from London.

In conclusion, Indian cities require policy action at two levels. On the demand side, municipalities should adopt liberal planning regulations, such as those in Japan, that encourage renewal and vertical development, where feasible. The development of infrastructure,ties should complement thi roads and utilis. On the supply side, all transportation investments, especially metro rails, BRTS, or bus routes, should be approved only after easing planning regulations to permit significantly increased FAR and mixed-use developments around mass transit stations. This post provides more details on how to achieve such renewal.