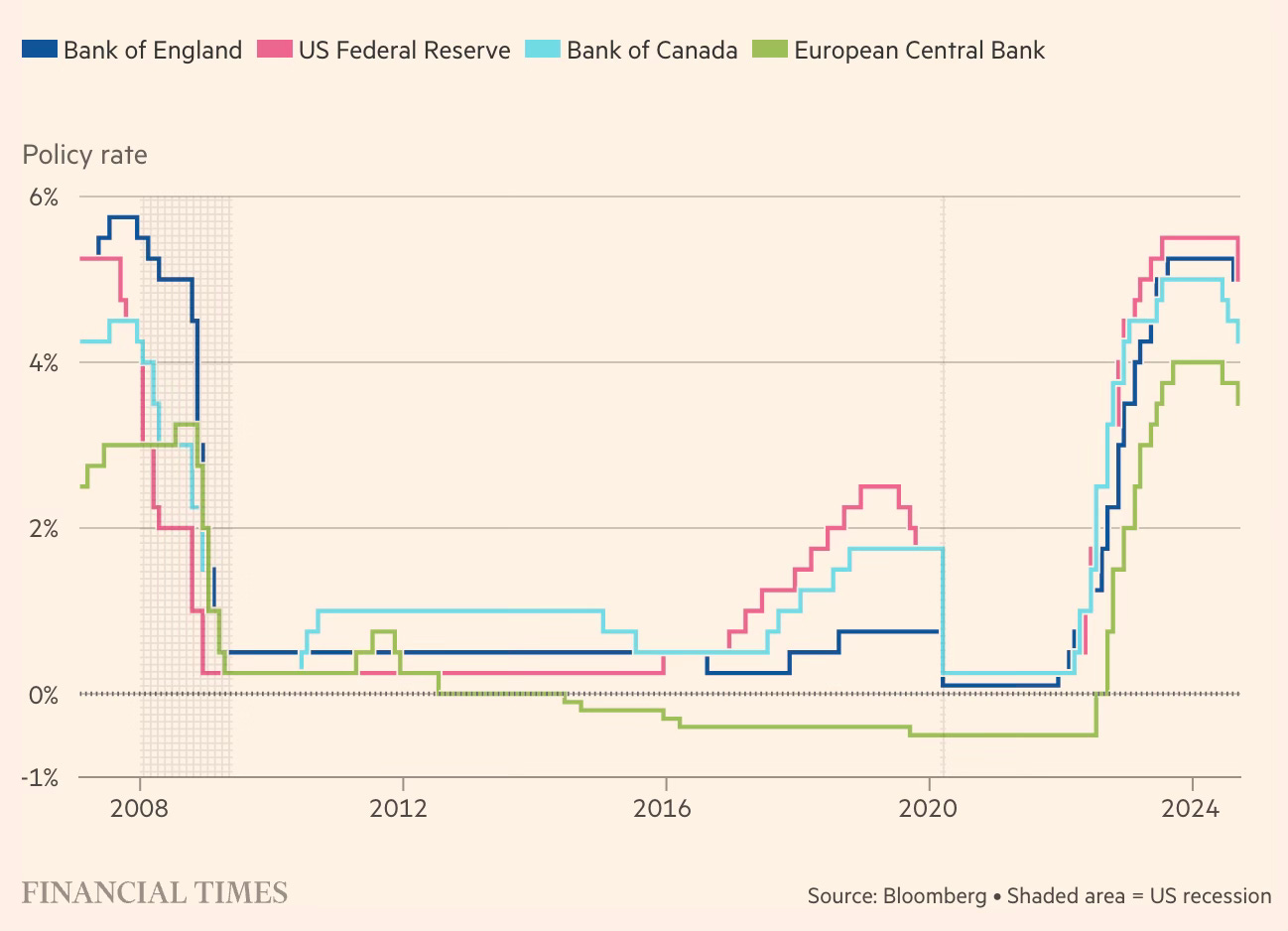

1. Changes in interest rates from June till 20th September 2024.

2. The long US equity market run.3. This is the graphic on how inflation was tamed.And this is the graphic on how monetary policy responded.Inflation across advanced economies exceeded 7 per cent in 2022 while nearing 10 per cent in emerging markets. As official interest rates surged in 2022, the World Bank was among the institutions flagging the risk of a global downturn. Analysis by Oxford Economics shows that of 42 rate raising cycles since the 1950s in the US, UK, Germany or the Eurozone, and Japan, those associated with recessions outnumber those without by two to one. Instead, the US has helped the world economy weather the synchronised rate-raising cycle unexpectedly well, with the IMF predicting global growth of a respectable 3.2 per cent this year. “This is a very different easing cycle than most other ones,” says Seth Carpenter, the global chief economist at Morgan Stanley who spent 15 years at the Fed. “Most other easing cycles happen because of recession.” The US economy is expanding at a solid clip, with the Atlanta Fed estimating this week that GDP growth will rise to about 3 per cent for the third quarter. The US labour market has lost some momentum as inflation has collapsed from a peak of about 7 per cent in 2022 to 2.5 per cent as of July, measured by the personal consumption expenditures price index. Demand for workers has cooled off at the margins as the unemployment rate has risen, but much of that increase has been driven by higher supply from rising immigration, economists say...

Yannis Stournaras, governor of the Bank Of Greece notes that Eurozone inflation has fallen from 10.6 per cent in October 2022 to 2.2 per cent now. “We brought it down in just 18 months and managed to have a soft landing in the economy.” The fact that the ECB from mid-2022 could raise interest rates by an unprecedented 450 basis points within 14 months without pushing the economy off a cliff is remarkable, says Piet Haines Christiansen, a ECB strategist at Danske Bank. “Two years ago, most economists would have said that such a dramatic increase would result in a deep recession.”

The Minerals Security Partnership, a coalition of 14 nations and the European Commission, will unveil a new financing network at an event in New York on Monday as they try to ramp up international collaboration and pledge financial support for a huge nickel project in Tanzania, backed by mining company BHP. A joint statement due to be published on the margins of the UN general assembly says the network will “strengthen co-operation and promote information exchange and co-financing”. It lists 10 critical minerals projects that have already attracted support from MSP partner governments. Representatives of BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Rio Tinto and Anglo American are scheduled to attend the meeting, amid a push to attract private investors and miners to invest further in the sector. Jose Fernandez, US under-secretary of state for economic growth, said a further 30 critical minerals mining projects are being evaluated by the MSP, as western governments race to secure the raw materials needed to make everything from electric vehicles to advanced weapons... The US, Australia, Canada, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Norway, Sweden, the UK, and the EU are members of the MSP.

5. An important part of Candidate Trump's Maganomics

A second term of Trump would see levies on imports supercharged to levels last seen during the 1930s following the passing of the landmark protectionist Smoot Hawley Tariff Act. After initially saying he wanted to impose 10 per cent tariffs on all imported goods, Trump has recently said they could be up to 20 per cent. For Chinese imports, he has talked about imposing a 60 per cent tariff. This month he said countries that planned to reduce their dependence on the dollar would also be hit with 100 per cent tariffs as punishment. Trump hopes the trade barriers will not only raise revenues, but lead to the restoration of US manufacturing...

If enacted, they represent a return to an era where substantial chunks of government revenue came from trade tariffs, rather than from taxes on people’s incomes and the profits of businesses... The Peterson Institute for International Economics think-tank in Washington calculates that 20 per cent across-the-board tariffs combined with a 60 per cent tariff on China would trigger a rise of up to $2,600 a year in what the average household spends on goods... PIIE senior fellows Obstfeld and Kimberly Clausing think that the maximum amount of additional revenue the administration can raise — by applying a 50 per cent tariff on everything — would be $780bn.

Chinese officials are now combining the heft of state spending and financial support with top-down directives to buy local tech, particularly in semiconductors. Late last year state buyers were directed to phase out computers powered by American processors. Since implementing the directive in March, central agencies have transitioned from exclusively purchasing laptops running on Intel and AMD processors last year to now acquiring three-quarters of their devices with chips from Chinese companies such as Huawei, Shanghai Zhaoxin and Phytium, according to public records. Huawei’s Qingyun L540 has won a majority of the orders. What kicked off as a campaign to cut foreign tech products out of the offices of governments and state-owned groups has gradually expanded into a wider array of products. Automakers, including major European groups that produce cars in joint ventures with Chinese state-owned firms, have been directed to step up their use of domestic semiconductors, according to four people familiar with the matter. Two of the people said they had been given a target to use Chinese chips for 25 per cent of the total by next year, though there were not yet consequences for failing to do so.

8. A debate rages in Australia on a Parliamentary vote to reform the Reserve Bank of Australia and establish a dedicated monetary policy Board within it to decide on interest rates. The vote has left parties sharply divided with the Greens' demand being the most interesting.

But the Greens said this week they would only support the bill if the government used its powers to override the RBA and force it to cut interest rates — or if the bank did so of its own volition — arguing that monetary easing was necessary to help renters and mortgage holders. Both major parties derided the Greens’ proposal, saying that forcing the RBA to cut rates would undermine its independence. “They’re economic terrorists and you can quote me on that,” Taylor said at the prospect. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said on Monday that acceding to the Greens’ demand would amount to undermining the independence of the central bank in order to pass legislation strengthening its independence. But the Greens questioned why the central bank should be treated as “above politics”. “The RBA board are not infallible high priests of the economy who are above criticism,” said Nick McKim, a Greens senator. On Tuesday, the RBA board kept its key cash rate at 4.35 per cent for the tenth straight month, saying it maintained its view that inflation was not yet under control.

9. Interesting article on the topic of walkability-workability from metro to office in Tokyo.

In a September 10 note to clients, Goldman’s real estate analyst, Sachiko Okada, took a look at office relocation trends within central Tokyo, overlaying that with a calculation of average walking distances between offices and the nearest station — a metric commonly used in Japan’s commercial and residential real estate markets and pivotal in a metropolis where the overwhelming majority of commuters travel by rail. Okada’s analysis comes at a time when the five innermost wards of Tokyo have never looked so frenetic, with Godzilla-scale office construction in prime locations. Around 1.2mn square metres of new space is due to come on to the market in 2025, she says... But the issue, as ever, is location. For offices within Tokyo’s five central wards, the average walk from a station is a breezy three minutes 42 seconds, with 64 per cent within the four-minute walk zone that even the heaviest-footed sloth cannot grumble about. But a significant amount — roughly 7 per cent — lies outside an eight-minute walk. Back in the days where Japanese companies were routinely able to make staff feel grateful to have a job, and surveys showed far higher ratios of people prioritising their work over everything else, that was less of an issue. But now, with priorities shifting, labour more willing to quit and companies increasingly unable to meet their staffing targets, proximity to stations is yet another battleground in the war to attract and keep good staff.

Just 7% of work commutes in Tokyo falls outside the 8 minute walking time from metro to office!

10. Global EV sales have stagnated this year.

11. Coffee chains in India.