There’s a debate in India on whether food prices should form part of the inflation index that the Reserve Bank of India uses for its inflation-targeting monetary policy regime. The current IT regime has a CPI (Combined) inflation target of 4% with a band of 2-6%.

There are at least two reasons for arguing against keeping food out of the headline index. One, food inflation is caused mostly by supply-side factors like rainfall and other weather patterns that demand-side measures cannot influence. Worse still, monetary policy tightening in response to such supply shocks can compound the problem by acting as a pro-cyclical measure. Two, keeping interest rates high in response to inflationary pressures driven by food prices has adverse economy-wide impacts.

These are universally valid arguments and have been made for long by those who oppose having food prices included in the CPI index. In general, there has always been a well-founded concern that interest rate hikes are blunt when faced with price increases resulting from supply shocks like weather, pandemics, wars etc.

A nuanced reason for keeping out food components is that it betrays a bias against farmers. While higher prices hurt consumers, it must be acknowledged that it does benefit farmers as producers. To this extent, the presence of food prices in the index (and consequent actions to bring them down) ends up hurting farmers. There’s an asymmetricity in this response given that monetary policy does nothing to stabilise the prices upwards if food price inflation is negative.

There’s merit in this argument since there’s enough evidence that the Indian farmers suffer from adverse terms of tradewhich is exacerbated by government policies like bans on imports, exports, open market sales etc. And now monetary policy adds to the set of such policies. This becomes especially relevant to agriculture crops which are prone to very high price volatility over the years.

However, there are several reasons to take these arguments with caution. For a start, there’s a large body of evidence that points to the strong causal link between inflation

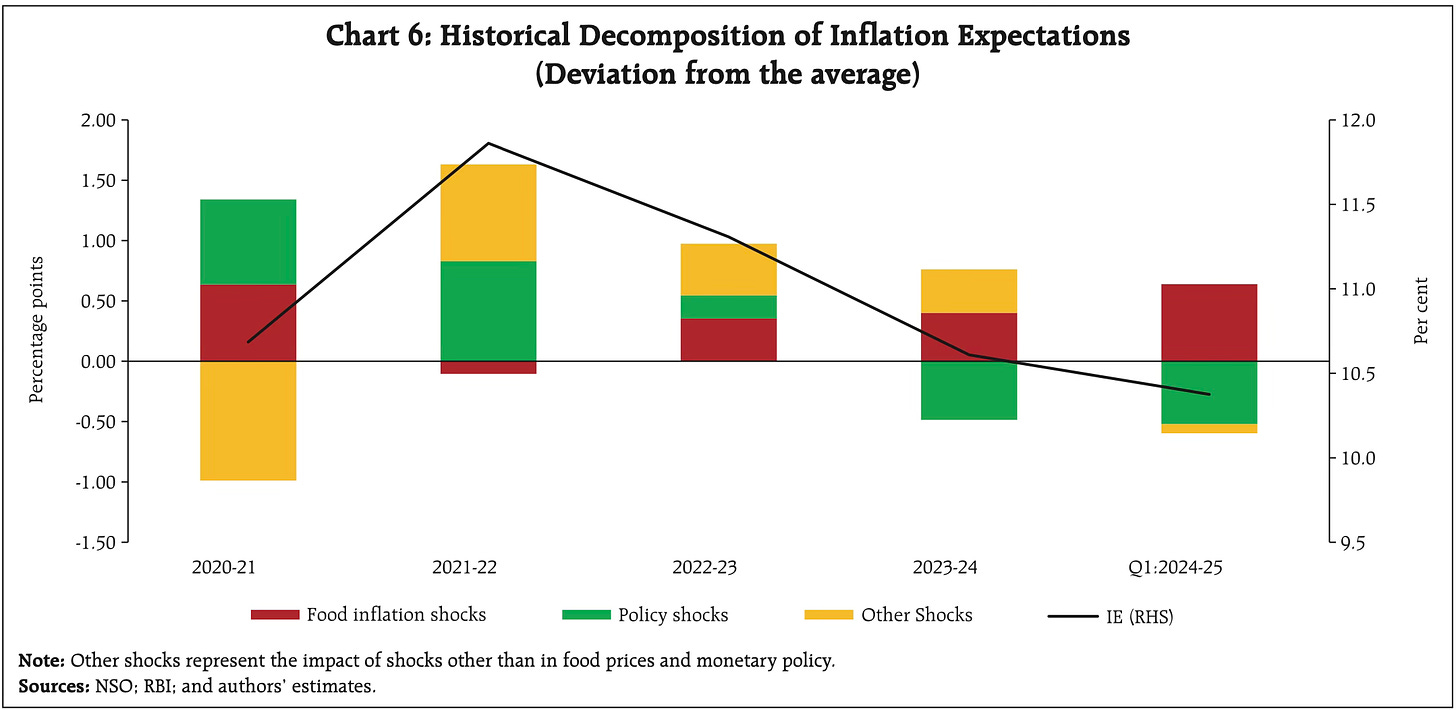

A very good case against any modification to the inflation index used by RBI is made here by the RBI economists themselves, and here. In fact, the RBI report shows how food inflation has come to have an increasingly high role in inflation expectations.

Besides, there are other empirical arguments to stay the course. Consider this analysis by Tulsi Jayakumar of the monthly CPI and food inflation data for April 2014 to July 2024.

We found that CPI inflation exceeded 6% in 34 of the 124 months studied (27% of the time), while in two months it was less than 2%. On the other hand, in 52 of the 124 months (42% of the time), food inflation was above 6%. Notably, in 20 months, food inflation was below 2%, of which seven months recorded negative inflation, while 13 months recorded positive but under 2% inflation… A more granular analysis reveals that food inflation was actually below the CPI-C rate in 64 of the 124 months, while in one month both were the same. Thus, in 52.4% of the months, food inflation remained equal to or below the retail rate, with the peak negative deviation taking a value of (-)4.01 percentage points; and 59 of the 124 months had food inflation exceeding the general rate, with a peak positive deviation of 4.8 points.

These figures show that food inflation has not been wildly distorting the CPI inflation data. It also underscores the tight relationship between CPI and food inflation.

The analysis also points to the dissonance between inflation and inflation expectations (median three-month ahead and median one-year ahead between December 2015 and July 2024) in India and how it could widen further if the food component is removed from the inflation index used in IT.

Interestingly, even in the months when food inflation was negative, inflationary expectations (for both time spans) were significantly higher than actual inflation. For instance, in June 2017, when current inflation was 1.46% and food inflation was -1.17%, inflation expected three months ahead was 7.5% and one-year ahead was 8.6%—5.1 and 5.9 times the actual rates. From December 2015 to July 2024, the average three-month ahead inflationary expectation has been twice the actual inflation, while the average one-year ahead expectation has been 2.2 times actual inflation… While inflation has moved away from the 2-6% target band’s upper limit set under India’s inflation-targeting framework only 27% of the time, inflationary expectations have remained ‘unanchored’ throughout this period, with expectations hovering above 7.2% and 7.9% respectively on both time-ahead scales. Over the span of December 2015 to July 2024, peak inflationary expectations for the three-month ahead and one-year ahead period touched 12.3% and 12.6% respectively. A central bank monetary policy that disregards food inflation, which so clearly drives inflationary expectations, will not be seen as credible, which could lead to those expectations getting unanchored even more. This would risk setting off a vicious cycle of high inflationary expectations followed by higher trend inflation.

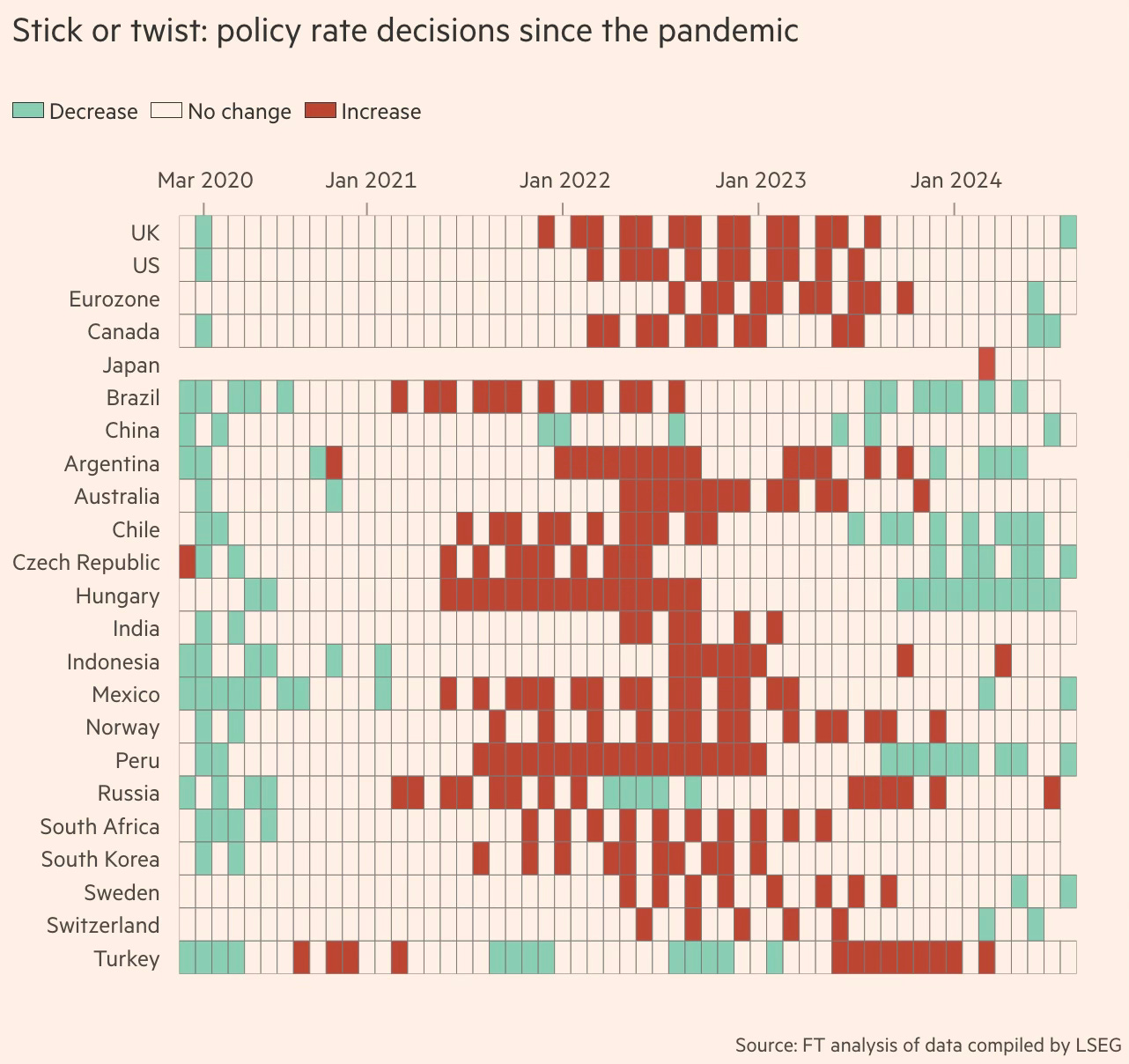

A second illustration shows that since the pandemic, apart from the Bank of Japan and the Swiss Central Bank, the RBI has undertaken the least number of interest rate changes. And rate hikes too.

While it’s arguable as to what’s responsible for such strongly anchored inflation, clearly the RBI’s current IT regime has been associated with remarkable monetary policy stability during the tumultuous period during the pandemic and its aftermath.

In addition, there are a few other points worth considering in favour of retaining the food components in the inflation index used for IT.

1. In a lower middle-income country like India where the vast majority of people survive at subsistence incomes, where at least 40% of the consumption basket consists of food, it’s important that governments keep food prices stability as a top priority. And the CPI inflation index is the salient indicator of inflation that feeds into public debates on price trends.

It’s therefore important for the political economy that that component of price level trends that impacts people the most is captured in the central policy framework that engages on the issue of inflation.

2. The theory of adaptive expectations informs that current inflation (and other macroeconomic trends) shape people’s expectations about future inflation. The increasing price levels as felt by consumers, irrespective of their source, will feed into inflation expectations. And if the price levels rise on the largest component of the consumption basket, it inevitably shapes expectations.

3. The classic pathway for inflationary expectations to take hold is the wage-price spiral. People feel the pinch of the rising costs of their consumption basket and demand higher wages. Irrespective of whether the CPI index consists of food or not, if the consumption basket feels inflated then it sets the stage for the wage-price spiral.

The reasons posited in the second and third points are empirically borne out in the vast body of research that explores the links between food prices and core inflation. In conclusion it can be argued that food consumption being essential is inelastic, and also forms a very large share of the Indian consumer basket, and therefore any food price increase invariably leaks out as economy-wide inflation.

It’s important to eschew any quick fixes and wish away the challenging struggle for price stability. A lower inflation figure achieved by stripping out the food component cannot overlook the reality of rising prices impacting the major part of the consumption basket for the vast majority of Indians. Likewise, it cannot also be used as the fig leaf by the central bank to lower rates. Any temporary relief achieved by such means is only likely to create bigger problems ahead.

In any case, the RBI is a professional technocratic institution. It clearly understands the limitations of using interest rates to dampen price rises arising from supply shocks. It does not pursue monetary policy based on a mechanistic application of headline rates into an objective function. It uses the collective judgment of the MPC on its interest rate decisions. It considers the contributors of inflation and its impact on the economy-wide aggregate prices, and whether interest rate decisions can influence those contributors (like with inflation arising from supply shocks).

For this reason, there is a distinction already existing between headline and core inflation levels. Central banks like the RBI consider the trends on both inflation indices while making decisions.

None of the arguments here should be taken to mean that there’s nothing wrong with the current IT regime nor it should not be tweaked at the margins. The short point is that deleting the food components from RBI’s IT regime may not be advisable.

No comments:

Post a Comment