Econ 101 informs us that R&D investments spur innovation and productivity growth, which in turn lower production costs and create newer products, boost consumption, drive further investments, job creation and economic growth. In short, R&D investments and innovation trigger a virtuous loop.

Gillian Tett points to an interesting paradox that questions this conventional wisdom that R&D investments invariably result in innovation, productivity growth, and expansion of economic output. Sample some numbers.

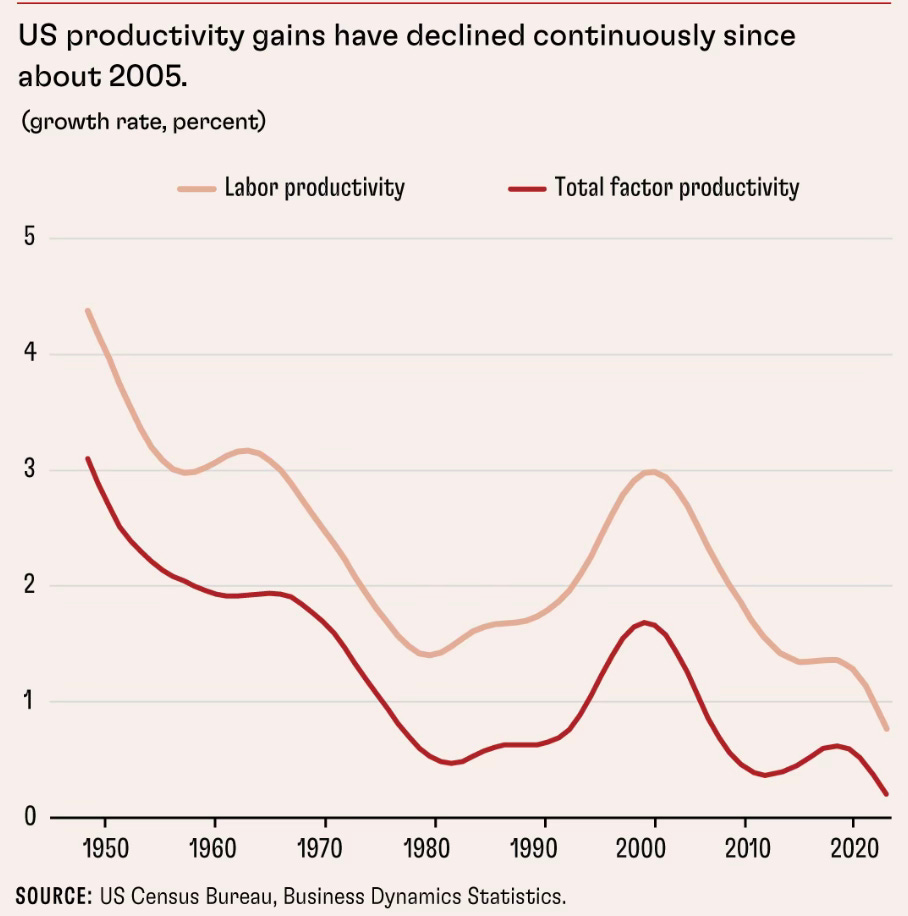

On the one hand, American R&D has risen in recent decades, from 2.2 per cent of GDP in the 1980s to 3.4 per cent in 2021. That reflects a doubling of private sector R&D to 2.5 per cent of GDP. Meanwhile, the proportion of the population involved in patent production nearly doubled in this period. But there is a big catch. Although “conventional economic models” imply that increases in R&D spending on this scale “should have led to accelerated economic growth”, this has not occurred. Michael Peters, a Yale economist, lays out the grim news: while labour productivity rose on average by 2.3 per cent between 1947 and 2005, between 2005 and 2018 it fell to 1.3 per cent. This cost America a putative $11tn of output, he calculates.

Micheal Peters in the IMF’s latest F&D magazine points to the US productivity growth being on a secular decline, that has become pronounced during the digital age since the turn of the millennium.

There is growing evidence that the US economy is not as dynamic as it used to be. A key aspect of business dynamism is new business formation. It is often measured by the entry rate, or the share of enterprises that started operating in a given year. The entry rate fell from 13 percent in 1980 to 8 percent in 2018, according to the US Census Bureau. In addition, US enterprises became substantially larger, with the average number of employees rising from 20 in 1980 to 24 by 2018. Older and bigger companies thus account for a much larger share of economic activity than they used to. These trends indicate significantly declining dynamism in the US economy over almost four decades…

First, the rise in corporate concentration has been shown to go hand in hand with expanding market power. The average markup by publicly traded US companies surged from about 20 percent in 1980 to 60 percent today. Large incumbent businesses thus seem to be shielded more and more from competition, allowing them to jack up prices and widen profit margins. A second line of research shows the flip side of rising corporate market power: the weakening of workers’ bargaining position. Since 1980, labor’s share of the US economy has fallen by about 5 percentage points. The plunge was faster in industries that experienced more concentration… Third, there has been a secular decline in business-to-business reallocation since the late 1980s, as shown in a series of papers by John Haltiwanger and other researchers. This suggests that the process of workers moving from declining to expanding businesses is not as fluid and dynamic as it once was.

Peters also explores the possible causes for this productivity decline.

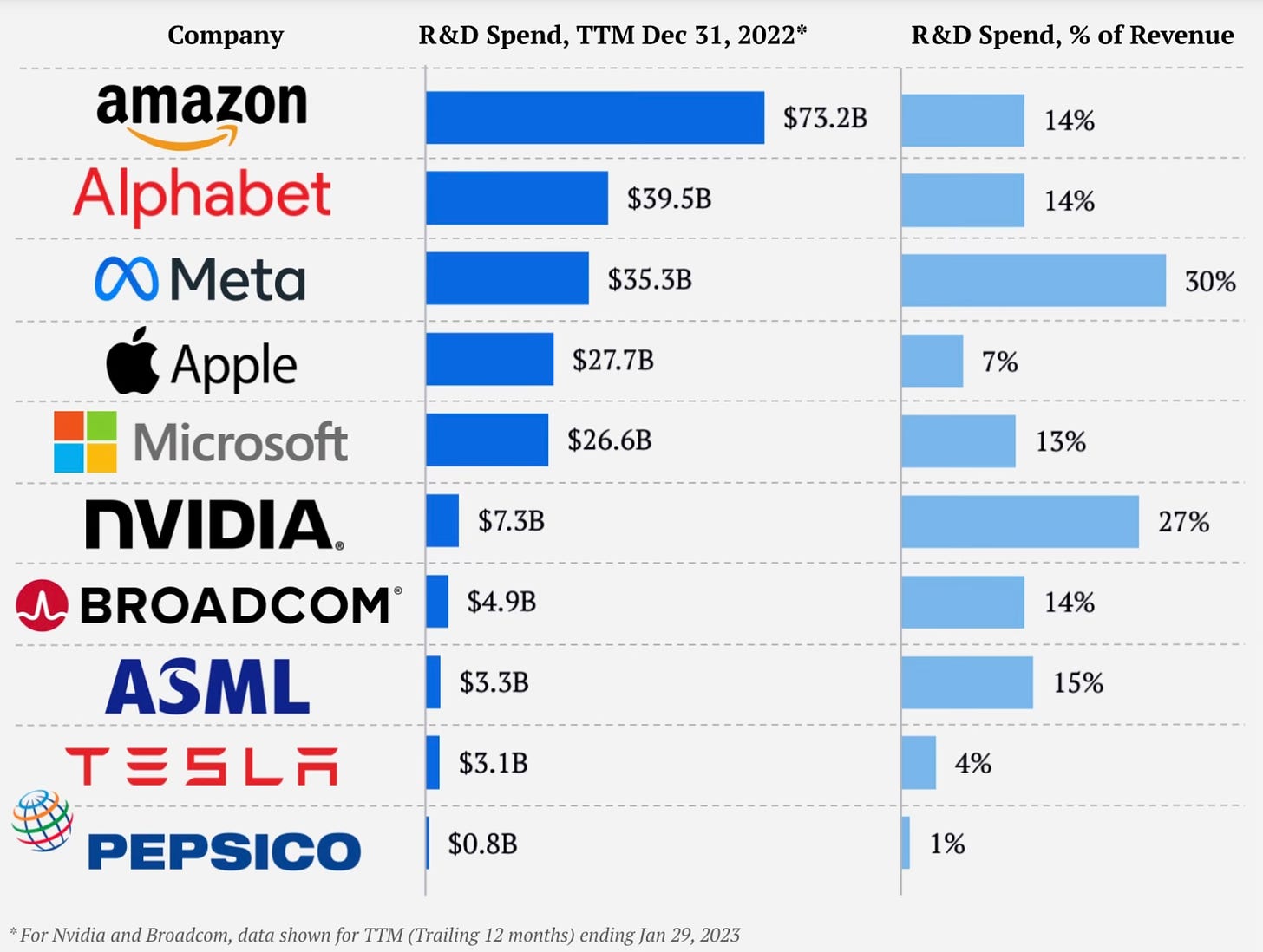

The ten biggest tech companies by capitalisation in Nasdaq spent a total of $222 bn in R&D in 2022, of which Amazon alone spent $73.2 bn.

Remarkably, these kinds of R&D expenditures have not been accompanied by job creation. As an illustration, even as Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet spent a record $139.3 bn on R&D, the three laid off 40,000 workers at the beginning of 2023.

Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon measured the evolution of dominant firms in the US since 1960 (top 20 firms by global sales and top 4 firms in each 3-digit industry) and globally since 1990 (top 100 firms by global sales in a given year and the top 20 firms in 25 industries), and found that their contribution to aggregate productivity growth has fallen by more than one-third since 2000.

In another paper Philippon writes

I estimate that markups in the United States have increased by about 12% since 2000. Such an increase in markups implies that wages and consumption are at least 10% below their potential… increasing markups in the United States have lowered labor income by about $1.44 trillion… the stars of the digital economy—Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft (GAFAMs for short)—are not as “special” as one might think… Along all qualitative dimensions, including profit margins and productivity, the stars of today are… they are smaller than market leaders of the past, and they matter less for overall GDP growth than General Motors, IBM, or AT&T did at their peak… rising market concentration since the early 2000s has produced market inefficiencies. Dominant firms have succeeded in erecting barriers to entry, which has resulted in lower investment, higher prices, and slower productivity growth.

Given the aforementioned facts, here are some observations:

1. Joel Mokyr has made the distinction of useful knowledge as one that promotes material progress. It consists of propositional knowledge (“what”) and prescriptive knowledge (“how”), with the former consisting of people who know things (savants) and the latter of people who make things (fabricants). He uses this distinction to explain why the Industrial Revolution originated in England and not in continental Europe. On the same lines, it may be useful to make the distinction within R&D investments and categorise some as useful R&D. Ditto with innovation.

Are R&D expenditure and innovation increasing the economic output? Is it creating jobs? Or is it being used to create moats around the markets served by the big technology companies? Given the nature of the digital technology markets, with their network effects and the advantages conferred by access to large data, are the large R&D expenditures conferring an unbridgeable advantage to the large incumbents?

There’s a case for distinguishing between defensive and productive R&D, with the latter aimed at protecting the turf/market. More on this latter in the post.

2. In the last 2-3 years, there has been a surge in AI-related R&D investments. As the graph above shows, each of the US Big Tech firms - Amazon, Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, Nvidia etc. - have been making AI-related investments in the tens of billions of dollars every year. So much so that the entire US equity market is now riding almost entirely on the AI investment boom. However several questions are being raised about the likely value generation from these investments. The vast majority of commentators view this boom as being driven by FOMO and disconnected from any value creation.

Is it then the case that the returns from R&D investments, or their productivity, have declined? Or is it that the technology will take time to mature and start to show its benefits? Or more generally, are large firms being inefficient in their allocation of R&D expenditures? Or a combination of all three?

Ufuk Akcigit writes in the same issue of the IMF’s F&D magazine:

In earlier research, Harvard’s William Kerr and I found that small businesses are more innovative relative to their size, suggesting they use R&D resources more efficiently. As companies grow and dominate their markets, they often shift their focus from innovation to protecting their market position. In a more recent study, Salome Baslandze, Francesca Lotti, and I showed using Italian data that larger enterprises tend to innovate less and instead engage in activities that limit competition. One such activity is hiring local politicians. As businesses climb the ranks among the largest 20 players in their industry, they hire more politicians, while their patent production declines. This highlights what we call a leadership paradox, where leading companies plow resources into maintaining dominance rather than fostering innovation… As dominant players prioritize strategic moves over genuine innovation, the economy as a whole is almost certainly missing out on potential growth opportunities.

3. Most importantly, it’ll be useful to examine where these R&D investments are going. These are astronomical sums, larger than the entire R&D expenditures of several large countries combined, including those like India. Are they actually going into research and development? Or is it some accounting trick to benefit from tax rules?

The primary reason to doubt these numbers is a palpable absence of their signatures on the products and services being delivered. Has e-commerce, social media engagement experience, and internet search got so much better in say, the last five years, to justify even a small part of these expenditures? Does building and maintaining data centres (whose buildings and operations are outsourced to PE funds and their boring infrastructure contractors) demand such levels of R&D expenditures?

It’s hard to imagine or rationalise that e-commerce, social media, and internet search (and advertising) can consume anything even remotely close to the amounts being spent on R&D. One associates with R&D in digital technologies to some equipment and software costs, and considerable manpower costs. Even at the higher end of such expenditures, $73.2 bn (and similarly high numbers in earlier years) appears mind-boggling. So where is this likely coming from (or what’s it going into)?

A comment on a discussion thread in Hacker News nails it:

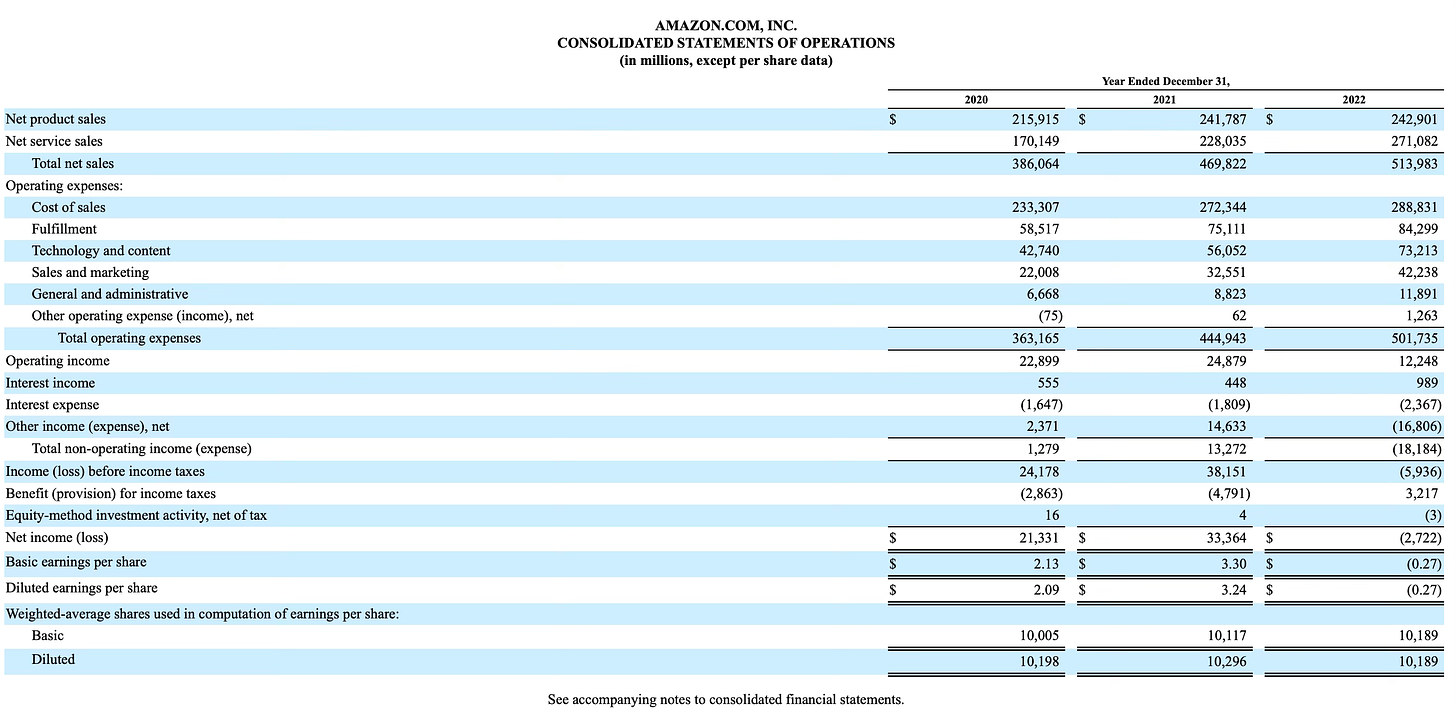

This $73.2B figure was pulled directly from their 2022 10-K filing under an operating expenses line item labeled technology and content, which includes R&D and then some. The devil in the details is buried in a footnote on p. 26:

Technology and content costs include payroll and related expenses for employees involved in the research and development of new and existing products and services, development, design, and maintenance of our stores, curation and display of products and services made available in our online stores, and infrastructure costs. Infrastructure costs include servers, networking equipment, and data center related depreciation and amortization, rent, utilities, and other expenses necessary to support AWS and other Amazon businesses.

At face value, to handwave this figure as just R&D and purport that it's directly comparable to other publicly-traded companies who report disaggregated research and development strikes me as somewhere between shotgun analysis and hoodwinking.

Read this Forbes article which says the same things, and see this.

Here is the table indicated above.

Amazon spends large amounts on its AWS data centres. All those expenditures are lumped together into the basket of technology and content. Even its prime Video content is classified under R&D. In short, it appears that Amazon lumps all its personnel, software and hardware costs under R&D.

Is all this disingenuous accounting motivated by tax minimisation strategies adopted by these companies? Is Amazon benefiting from the greater tax benefits accorded to R&D expenses? Akcigit again

The Federal Reserve’s Sina Ates and I examined market competition trends in the US over the past several decades. Since the early 1980s, there’s been a noticeable increase in market concentration and a decline in business dynamism… This period aligns with the 1981 introduction of the R&D tax credit, a component of President Ronald Reagan’s sweeping Economic Recovery Tax Act. The credit was intended to encourage businesses to invest in research and development. Minnesota was the first state to adopt a similar state-level R&D tax credit, in 1982, and many other states followed, expecting to promote innovation and economic growth. Which companies are most likely to take advantage of the R&D tax credit? Our research with Goldschlag shows that large businesses are much more likely to benefit than smaller ones. The policy—perhaps unintentionally—favors big companies, encouraging them to dominate in R&D spending… Our research provides direct evidence that businesses actively claiming R&D tax credits are more likely to engage in stifling hiring practices. These enterprises often offer higher salaries to inventors, and the inventors become less innovative after joining.

It’s therefore clear that all the so-called R&D expenditures are mostly about the general operational and capital expenses! So after all, real R&D expenditures might not have gone up as much as we imagine, which also explains the apparent paradox of low productivity growth.

4. In this context, it’s also worth making the distinction between the R&D expenditures of firms in digital technology and traditional economy sectors. Technology firms like those above are constantly iterating and improving their algorithms and user interfaces (and the logistics operations in the case of Amazon and advertising engine in the case of Google) as part of their regular operations. The nature of digital technologies (for example, with digital trails that serve as fuel for data analytics and AI-algorithms) ensures such iteration and refinement.

There’s an indistinguishable line between the R&D expenditures of technology firms and their operational expenses. It’s different from the distinct role of R&D in the traditional economy where it’s about inventing new technologies, products, and services. The likes of Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Apple etc., have not brought out any new product, but are only marginally refining their algorithms and at best moving into emerging adjacent markets (where too they have a head start due to the nature of their platform business models). They are, for all practical purposes, one trick ponies.

This raises the need for greater clarity in the accounting of R&D expenses of digital technology firms.

5. One of the surprisingly less discussed but widely known features of technology markets today is the stifling grip exercised by the big firms. This hold covers hiring and retaining critical personnel, patent acquisition, protection of their own patents, and even protecting themselves from being gobbled up. Big Tech (and large incumbents generally) firms employ armies of lawyers to engage in the likes of patent trolling, squatting, and hoarding to copy, steal and intimidate startups.

More from Ufuk Akcigit

Over the past two decades, there has been a notable reallocation of innovative resources toward large, established companies, Goldschlag and I documented in 2022. At the beginning of this century, roughly 48 percent of American inventors worked for these big incumbent companies—those that are more than 20 years old and employ more than 1,000 workers. By 2015, that figure had surged to 58 percent, marking a significant shift in where the nation’s innovative talent is concentrated… research shows a concerning trend: inventors that move to large firms become less innovative compared with inventors that move to young firms.

A specific practice identified in our research is innovation-stifling hiring. This occurs when big, established enterprises hire key employees from younger competitors, often by offering higher salaries. However, instead of using these new employees to drive innovation, the big businesses may place them in roles that do not fully leverage their skills. As a result, these individuals become less innovative, and the overall innovative capacity of the economy suffers. After 2000, there was a notable increase in the wage premium offered by established companies, compared with salaries paid by younger businesses. The pay differential widened by 20 percent, prompting many innovators to switch jobs and join larger, well-established companies. However, these inventors’ innovativeness dropped by 6 percent compared with that of their peers who joined younger employers… By hiring away top talent from rivals, these companies not only weaken their competitors but also prevent these individuals from contributing to potentially disruptive innovations elsewhere. This strategy may benefit the hiring business in the short term, but it poses a long-term risk to the economy’s overall innovation and growth.

Given all these, startups stand little or no chance of competing with large incumbents. It’s an open secret that the Big Tech firms unleash their lawyers and financiers to intimidate and squeeze any startup trying to compete with them. I don’t know whether the libertarians and tech evangelists who wax eloquent about digital utopia and lose no opportunity to argue for deregulation and getting government out of the way are being ignorant or disingenuous or plain dishonest when they overlook the egregious manner in which Big Tech firms unleash their lawyers and corporate brokers to intimidate startups.

Why are none of the economists in the big Economics Departments silent about one of the commonest market practices which is also the biggest threat to competition in digital markets?

I have written here (and here) about how Amazon uses anti-competitive practices to copy and forcibly buyout emerging startup competitors and then kill off their technologies or adopt them itself.

The final word to Akcigit

The evidence suggests that while the US is investing more in R&D, the concentration of resources among large businesses has led to diminishing returns in terms of productivity growth. This outcome challenges the assumption that simply expanding R&D spending will automatically lead to economic growth. Instead, it highlights the need for a more nuanced approach to industrial policy—one that not only incentivizes R&D but also encourages the effective reallocation of resources. To foster a more dynamic and innovative economy, the US needs to design policies that support not just large incumbents but also smaller businesses and start-ups, which often have a greater capacity for disruptive innovation. This could include targeted tax credits for small businesses, grants for early-stage innovation, and policies that encourage competition and reduce barriers to entry for new players.

No comments:

Post a Comment