The front end of the emerging new Cold War is trade. Specifically, the protectionist walls that are emerging around the world, led by the United States, against Chinese goods and services. It has naturally riled those who believe in the orthodoxy of free-trade.

In that context, Rana Faroohar asks a couple of incisive questions.

What’s the point of trying to tally up the potential economic costs of tariffs based on models that assume an even global playing field, when no country, certainly not a rich one with decent environmental and labour standards, could compete on price with China in any area of production? Why argue that the world should simply accept massive Chinese dumping of clean tech as a solution to global warming, when the true carbon cost of producing such goods with coal power, as well as the emissions involved in shipping them, aren’t even factored into those calculations? Transport emissions from durable goods are the second-largest source of global emissions after China itself.

This post will make the case that the conventional free trade theories don’t hold when we are talking about China.

The theory of comparative advantage refers to a country’s ability to produce a good or service more efficiently and competitively (or at a lower opportunity cost) than its peers. It informs that everyone benefits if countries produce those goods/services in which they have a comparative advantage and trade among themselves. The case for free trade rests on the theory of comparative advantage.

There are several assumptions implicit here. There are specifically five that concern me, each disturbed by the uniqueness of China.

First, the most important assumption in the case for free trade is that each country has a comparative advantage in some goods they can trade. But what if one country has a competitive advantage in too many goods, leaving others with a competitive advantage in too few? Would the former sacrifice its competitive advantages across industry segments and focus only on the few where its advantages are the highest?

It’s no good for an economy if all it does is import at lower prices from another economy and has little in turn to export. Michael Pettis makes an important point in the context of a Paul Krugman oped where he alludes to “cheap imports” making a country richer.

The wealth of a nation, as Adam Smith reminded us, is the value of goods and services produced by the residents of that nation, and the only thing that makes a nation richer is an increase in that value. "Cheap" imports help only to the extent that they increase the real value of goods and services produced domestically, but that can only happen if imports are paid for by exports of goods and services, and not by exports of claims on domestic assets. That is why comparative advantage makes everyone richer, while competitive advantage, based on suppressing domestic wages, makes the world poorer (although the surplus nation richer).

There’s overwhelming empirical evidence from across developed and developing countries that cheap Chinese imports have weakened, and in many cases decimated, the domestic manufacturing bases and inflicted massive job losses. While cheap imports benefit consumers with lower prices, their indirect benefits hardly offset the costs. While there is a David Autor et al study that anchors the argument in the case of the US, there will be several similar examples (however not yet rigorously researched and published) from across the world that bear testament to the damage done to local communities and whole industries by the flood of Chinese imports.

Simplistic concepts and toy models that work well in small and simple systems cannot be blindly extrapolated to explain the complex world economy and justify decisions that have far-reaching economic and political consequences for the world as a whole.

Second, a related assumption is that there’s a level playing field among competitors across countries, without trade-distorting subsidies. What if one economy unfairly subsidises its companies as to give them an unfair advantage over foreign competitors?

This issue manifests in the nature of Chinese subsidies. While it supports domestic manufacturers with copious direct subsidies, they are supplemented with indirect subsidies that amplify the problems.

China’s support for its electric-vehicle industry included clever inducements to demand, such as reduced parking fees and free licence plates. Buyers are still able to benefit from a tax break worth up to 30,000 yuan ($4,100). Other subsidies were not directed at consumers, but could be passed on to them through lower prices. Together, they increased demand as well as supply, bolstering capacity utilisation and profits. China’s purchases of conventional cars, powered by internal-combustion engines, used to soak up almost all domestic production. Owing to the success of electric vehicles, that is no longer the case, meaning subsidies in one area have contributed to excess capacity in another. Conventional carmakers, many of them including joint ventures with foreign firms, have therefore turned to customers abroad.

Third, it’s also possible that one country has an interest in keeping the playing field tilted. What if one country consciously pursues an industrial policy of global dominance in certain sectors for whatever reasons (for strategic reasons or to off-load its excess capacity)?

While all countries pursue industrial policy, China does it at a scale and discipline that no other country can match. Besides, over-capacity arising from investment and export competition is part of a conscious industrial policy strategy. It’s also aligned with the traditional Chinese policy of overshooting targets.

The Times has a good summary of the Chinese economic strategy

Regulators restrict the investment options of Chinese households, which have little choice but to deposit enormous sums of money into banks at low interest rates. The banks then lend the money at low rates to start-ups and other businesses. According to China’s central bank, net lending for industry swelled to $670 billion last year from $83 billion in 2019. Beijing instructs local governments to help the chosen industries. The assistance takes the form of cheap land for factories, new highways for freight trucks, bullet train lines and other infrastructure. The Kiel Institute for the World Economy in Kiel, Germany, calculated in a study that more than 99 percent of Chinese companies whose stock traded publicly received direct government subsidies in 2022. China keeps factory wages low, which helps the competitiveness of its manufacturers. Residence permits limit the ability of rural families to move permanently to cities, where they would qualify for better job benefits. Independent labor unions are barred, and would-be organizers are detained by the police.

This is a summary of how China built up its automobile manufacturing capabilities by pursuing the aforesaid strategy.

By 2011, Beijing had begun requiring Western companies to transfer key technologies to operations in China if they wanted consumers in China to receive the same subsidies for imported electric cars that were being offered for cars made in China. Without the subsidies, automakers like General Motors and Ford Motor could not compete with electric cars made in China. Multinational automakers responded by pressuring their South Korean suppliers, which at the time led the electric car battery industry to build factories in China. Beijing went further in 2016 and declared that even electric cars made in China would qualify for consumer subsidies only if they used batteries from factories owned by Chinese companies. Even automakers like South Korea’s Hyundai abandoned the Chinese factories of South Korean battery manufacturers and switched their contracts to Chinese battery companies like CATL. Chinese companies now produce the majority of the world’s electric car batteries…

According to a new report from the Atlantic Council, a research group in Washington, China’s exports of lithium-ion batteries leaped to $65 billion last year from $13 billion in 2019. Nearly two-thirds of these exports went to Europe and North America. Much of the rest went to East Asia, where the batteries are often assembled into products that end up being sold to Europe or North America.

This is a similar summary of how China came to dominate the solar panels industry.

A tenfold expansion of China’s solar panel manufacturing capacityfrom 2008 to 2012 caused the world price of solar panels to drop about 75 percent. Many American and European factories closed. Three of China’s largest solar panel producers suffered financial collapses of their own as prices plunged, saddling banks with losses on loans. Smaller rivals in China were able to buy their factories for fractions of the original construction cost. This second generation of companies was then able to make panels more cheaply and invest in cutting-edge research. Chinese companies make almost all of the world’s solar panels. The country’s exports of solar cells, which the Biden administration is raising tariffs on, have more than doubled in the past four years, to $44 billion last year. China is ramping up twice as fast its exports of solar wafers, a key component.

The brilliant graphic below shows “the family resemblance in China’s early high-speed train models with their respective foreign JV partners”.

The industrial policy is complemented with measures that only a country like China can pull off. Consider these examples. The government can informally direct the business priorities and strategies of its firms - to shift from one part of the value chain to another or pivot from one sector to another. It can mobilise consumer opinion to shift from a foreign brand to a domestic brand. It can nurture local champions with a wink and a nod to banks and local governments. It can issue informal diktats and have local party cadres across all levels of the multinational corporation, including in the Boards. All these are deeply distorting and anti-competitive, but not illegal only because such practices are so unimaginable in any other country that they were never even considered possible when trade laws were formulated.

Fourth, what if the nature of the technologies, skills, and market structure is such that the comparative advantage and market dominance in certain industries give a country a head start in dominating another industry? What if there’s a self-reinforcing dynamic to such dominance that also prevents any decoupling or even diversification from the dominant country?

China has perfected an industrial policy strategy where they entice foreign firms with the allure of the massive domestic market and limited conditions to start with, gradually insist on technology transfers and joint ventures, and finally promote their firms to dominance in the market segment.

Kyle Chan has a very good article on how Chinese firms have come to become important and potentially dominant suppliers in the iPhone supply-chain - YMTC in NAND flash memory (gradually displacing Samsung and SK Hynix), Sunny Optical and AAC Technologies in camera lens (gradually eating into Largan Precision and GSEO), and Lens Technology for cover glass (squeezing out Samsung etc). On contract manufacturing, Chinese firms like Luxshare and Wingtech are already strong competitors to the Taiwanese trio of Foxconn, Pegatron, and Wistron.

Luxshare began by making cables and connectors for Apple’s products and later moved into iPhone production by acquiring Wistron’s iPhone plant in Kunshan in 2020. Apple itself has been helping China turn Luxshare into a “national champion,” sending engineers to help train Luxshare’s staff for years. Today, Luxshare is not only Foxconn’s primary competitor for iPhone production but was also selected by Apple as the exclusive manufacturer for its Vision Pro… Chinese officials got Apple CEO Tim Cook to sign a secret $275 billion deal in 2016 to help Apple’s Chinese suppliers move up the value chain… As “China’s biggest smartphone assembler,” Wingtech began by doing assembly work for smartphone brands like Vivo and Oppo as well as laptop brands like HP, Dell, and Lenovo. Now Wingtech is starting to make Apple products in its rapidly expanding production facilities in Kunming.

This trend is also accompanied by a trend to move across industries.

Chinese contract manufacturers are also moving deeper into the supply chain, into areas such as semiconductors. Wingtech bought Dutch chipmaker Nexperia in 2019 and then bought the UK’s largest chipmaker Newport Wafer Fab in 2021, which it later had to sell due to UK national security concerns. Luxshare has been building up its chip packaging capabilities by hiring Taiwanese semiconductor engineers. AirPods maker Goertek recently spun off its own chipmaking unit. These efforts are aimed not only at winning a greater share of the smartphone market but also at gearing up for EV production. For example, Luxshare is already partnering with Chinese automakers like Chery to make EVs.

The Chinese prowess in carbon-intensive heavy industry has been a critical contributor to driving the country’s clean technology advances.

Electric vehicles rely on a lot of aluminum… Overall, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) and full battery electric vehicles (BEVs) tend to use around 25% more aluminum than traditional gas-powered cars due to its lightweight properties… Chinese EV makers benefit from access to China’s vast aluminum industry, which makes up more than half of global production. This helps lower material costs, which are a significant factor in keeping overall costs low. And Chinese EV makers benefit from being able to work directly with producers of aluminum and aluminum products to develop specialized alloys and ensure stable supplies. Chinese state automaker SAIC partnered with Chinese state-owned Chalco, the world’s largest aluminum producer, to “jointly develop technologies to apply new aluminum materials to automobile parts.” BYD benefits from its close relationship with its top supplier for battery enclosures, Chongqing-based New Aluminum Era… EV parts like windows, seats, door panels, and bumpers are typically made from petrochemical products, like fiberglass… EV charging infrastructure also requires similar heavy industry commodities, like steel, aluminum, and cement. EV factories themselves require a lot of specialized metal alloys, such as for industrial robots and machine tools…

The construction of wind and solar plants relies on large amounts of heavy industry commodities, like steel and aluminum. According to analysis by BloombergNEF, solar requires around 33 tons of steel and 15 tons of aluminum for every megawatt of output… examples of industrial policy spillovers is the connection between steel, shipbuilding, and offshore wind. China’s heavily state-supported steel industry benefits its heavily state-supported shipbuilding industry, which makes up over half of global shipbuilding. China’s vast shipbuilding industry, in turn, allows it to make highly specialized, supermassive offshore wind turbine installation vessels (WTIV) that are large enough to transport and install wind turbine blades that can stretch over 100 meters. Of the WTIVs under construction, close to 90% are being made in China. China’s strength in steel and shipbuilding also helps it build specialized roll-on, roll-off (RORO) car-carrier ships for exporting Chinese EVs around the world. Chinese EV makers such as BYD have already launched their own car-carrier ships to transport thousands of vehicles to markets like Europe and Brazil… we can see a virtuous cycle forming between China’s heavy industry and its clean tech sectors. China’s heavy industry enables the production of EVs, solar panels, wind farms, power lines, and batteries.

BYD, now the country’s largest car maker, was more famous as an iPhone supplier than as a car maker and is s large contract manufacturer of iPads. This article explains how Tesla helped China develop its dominant EV manufacturing ecosystem.

China agreed to make special concessions to convince Tesla to build a plant in China. China changed its rules to allow the Shanghai Gigafactory to be a wholly foreign-owned subsidiary rather than a joint venture with a Chinese firm, as was previously required for all foreign automakers… this deal also benefited China’s own domestic EV industry by building up Chinese suppliers, such as Chinese battery giant CATL… The case of LK Group serves as a striking example. Tesla worked with LK Group, a Chinese maker of manufacturing equipment, to produce gigantic casting machines for what Tesla calls “gigacasting.” These casting machines allow Tesla to manufacture large auto components as a single continuous piece, which saves time, factory space, labor, and materials that would normally be needed to weld together many separate pieces. LK Group then went on to sell similar “gigacasting” machines to six Chinese firms, likely other automakers. Today, 95% of the components used in Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory are from China, and Chinese firms make up almost 40% of Tesla’s global EV battery supply chain… Tesla’s plant in China helped to turbocharge its domestic industry, creating not only jobs for Chinese workers at the Shanghai Gigafactory but also an upgraded supplier ecosystem for China’s own homegrown EV brands.

Tesla was the rainmaker for China’s EV industry.

Chan writes about the decoupling conundrum.

As companies like Apple move lower-end production out of China, China is moving up Apple’s production value chain into high-tech, high-value components. This echoes a similar finding from a Rhodium Group report: “Diversification has been taking place for years in these industries, but it has been obscured by a concomitant expansion of manufacturing value chains in China.”… As China moves up the value chain, this might create room at the lower end for countries like India and Vietnam to step in. But will the competitiveness of Chinese firms in the middle levels of the value chain create a ceiling on how far up other countries can go?…

One last thing to note is the virtuous cycle between Chinese brands and China’s broader manufacturing ecosystem. Much has been written on why it’s so hard for Apple to move iPhone production away from China, citing China’s vast and nimble supplier base. This supplier base, which Apple and Foxconn helped to develop, later empowered China’s own smartphone companies like Huawei, Xiaomi, and Oppo. Apple’s suppliers in China—like Samsung, SK hynix, Sunny Optical, and Lens Technology—supply similar components to its Chinese smartphone competitors. The kicker is that even as companies like Apple try to move away from China, China’s manufacturing ecosystem will continue to be supported and pushed forward by its own homegrown smartphone companies. And now these same Chinese suppliers are already supporting China’s expansion into other industries, like semiconductors and EVs.

The Chinese industrial policy is generating multiplier effects across industrial segments.

China’s solar industry benefited from its R&D on semiconductors. China’s high-speed rail built on its aerospace research. Chinese EVs draw directly on China’s smartphone supply chain. Many of the Chinese suppliers to Apple I discussed in my High Capacity piece overlap with the EV industry. These supply chain overlaps and technological spillovers are only growing as Chinese EVs increasingly become “smartphones on wheels.”… the companies now producing China’s most competitive EVs emerged directly from its electronics industry. Xiaomi, after all makes 15% of the world’s smartphones. CATL - now widely seen as the world’s best EV battery maker - began as a spin-off of Amperex Technology Ltd, or ATL, which makes smartphone batteries. The iPhone is in a sense the younger sister of the Chinese-made Volvo EX30: Both are Western-designed consumer electronics that are made in Chinese factories, through Chinese engineering expertise.

Finally, what if there are national security and other strategic considerations that dominate economic benefits in trade and other relationships?

The Cold War 2.0 is already on us. Nobody doubts China’s aggressive intentions of global dominance. China’s actions on the foreign policy front - border skirmishes with neighbours, the now routine transgressions of international coastal boundaries in the South China Sea, bullying of countries like Canada and Australia, political and industrial espionage in the US and Europe, interference in the domestic politics of several countries, the clandestine influence activities of the United Front Work Department, Wolf warrior diplomacy etc., - raises serious doubts about whether any engagement on good faith with China is even possible. It’s already a power fully convinced that biding the time is over, and the time has arrived for China to step up and recover its Middle Kingdom role. It’s therefore difficult to imagine the struggle between the US and China abating.

Faroohar again

There’s the elephant in the room: the fact that China has thrown its autocratic weight behind some of the world’s most repressive regimes, from Russia to Iran. These regimes are the enemies of all liberally minded people. Given this, do we really want to count on Beijing for essential goods? And even if China’s communist party wasn’t taking this road, haven’t the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the threat of conflict around Taiwan, shipping blockages in the Red Sea and any number of natural disasters provoking supply chain chaos over the past few years shown us that it’s not a good idea for the world to keep all its production eggs in one basket?

The pandemic has made everyone acutely aware of the dangers and risks of excessive dependence on China for manufactured goods. The diversification away from China is already underway among all major economies and multinational corporations operating in China. These measures are only going to tighten going forward.

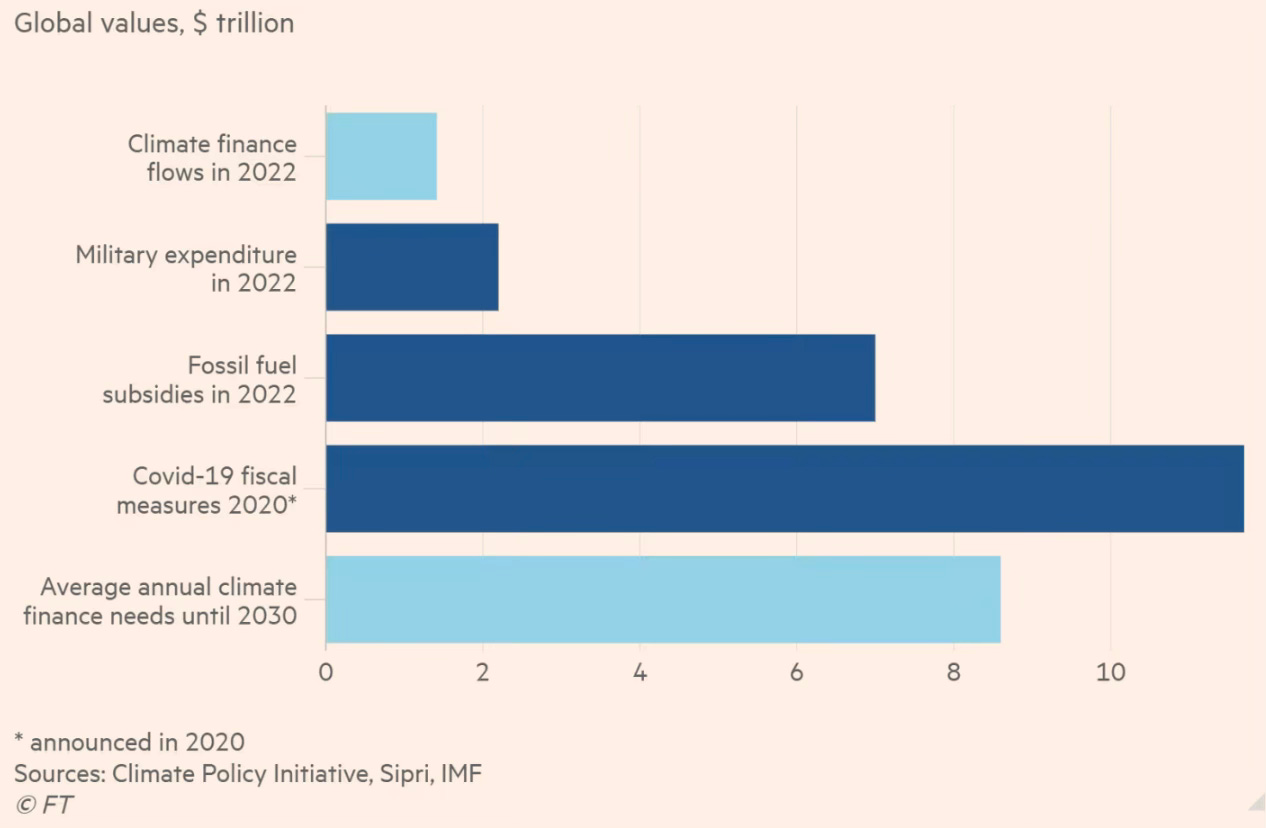

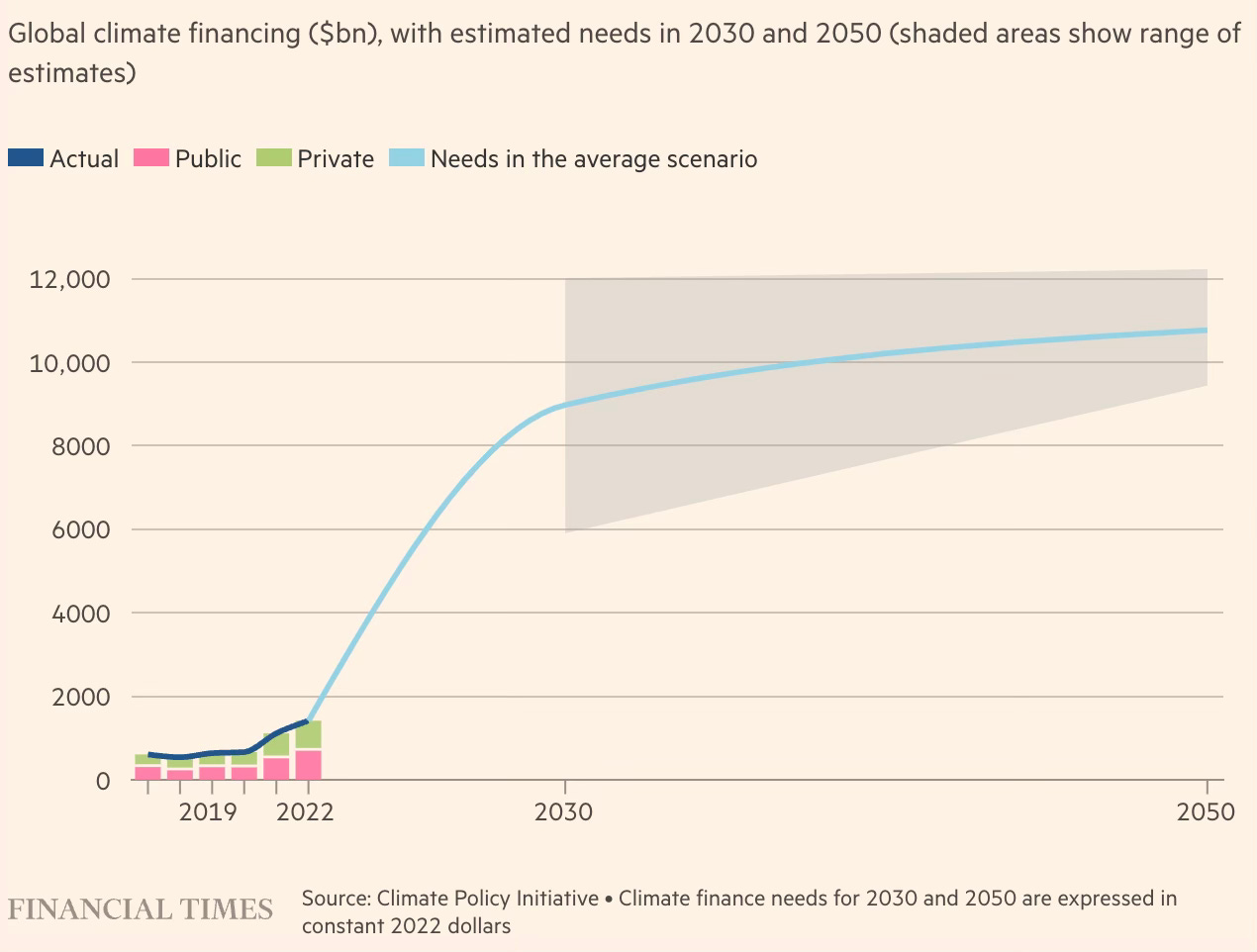

Amidst all this, there’s a popular view going around that Chinese subsidies and exports of green technologies are great for climate change and should therefore not be discouraged. Dani Rodrik critiques those who rail against Chinese green energy subsidies, arguing that they have dramatically reduced the prices of green technologies and expanded its access manifold. He argues that the need of the hour is more industrial policy and subsidies by all countries to make green technologies more affordable and accessible. He describes the case for subsidising green industries like China has done as "impeccable". However, he does acknowledge the problems with China's subsidies.

Countries have other interests besides the climate, of course. They can harbor legitimate concerns about the consequences of other countries’ green-industrial policies for jobs and innovative capacity at home. If they judge that these costs outweigh the climate and consumer benefits, they should be free to impose countervailing tariffs on imports, as trade rules already allow. It would be better for the world overall if they didn’t react that way, but nobody can or should stop them.

The problem is with the last line on overall benefits and costs. While the Chinese green power subsidies have achieved tremendous success in mainstreaming green technologies, it has come at the cost of destroying local green industries elsewhere and making all countries chronically dependent on China for green technologies. Given green technologies are a major share of today's and future manufacturing, the destruction of the domestic manufacturing bases across countries due to cheap Chinese exports is a prohibitive and unacceptable price to pay. It becomes a serious, almost existential, national security risk when there's a Cold War raging and the near-certain weaponisation of its dominance in these frontier technologies by the Chinese government.

The manufacturing trends in green technologies are an encore of what has happened across the manufacturing sectors in the last two decades. Thanks to the cheap Chinese imports, the manufacturing base that's essential to create the good jobs that Dani Rodrik frequently writes about has been seriously weakened across developed and developing countries. Besides, the world has become excessively dependent on China for even basic manufacturing, as the Covid 19 painfully exposed.

Economists should consider this trend in manufacturing as a failure of comparative advantage. If there's a strong Matthew Effect, whereby the dominant producer is able to strengthen their position with economies of scale and subsidies, and the nature of technology linkages across sectors, then comparative advantage and trade end up enriching the dominant producer while leaving the world economy worse off besides engendering unmitigable national security risks.

In the latest update on the Chinese economy, I blogged here that instead of rebalancing its economy China has sought to continue its investment-driven strategy, this time by exporting its way out of its current economic problems. Given the already rising suspicions and geopolitical tensions, this is bound to fuel protectionism in its trade partners.

Finally, since we discussed trade theory and China, I will conclude the post by drawing attention to the paradigm shift in the Western policies against China during the Trump administration, one that has continued and strengthened under the Biden administration. The views held by President Trump’s Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, were central to the shift. Derided by his own peers and influential experts then as a mediocre and journeyman economist, Litghthizer’s views have now become the bipartisan mainstream. He has said that it’s worth trading higher consumer prices for increased manufacturing employment.

“If all you chase is efficiency — if you think the person is better off on the unemployment line with a third 40-inch television than he is working with only two — then you’re not going to agree with me. There’s a group of people who think that consumption is the end. And my view is production is the end, and safe and happy communities are the end. You should be willing to pay a price for that.”

A recent WSJ article captured his views.

“I have migrated from thinking we need superficial fair trade to realizing that that is unachievable, and what we really need is balanced trade,” Lighthizer said in an interview in Palm Beach, Fla., where he lives a few miles from Mar-a-Lago. “Not balanced every year and with every country, but over time and globally.” He added: “Every country should be exporting in order to import. If you’re running chronic surpluses for decades, then you are by definition a protectionist. You’re engaging in industrial policy to help yourself, you’re transferring resources from your consumers to your producers, you’re trying to … acquire other countries’ assets.” These used to be called beggar-thy-neighbor policies, he said, “and they have to stop.”.. Mainstream thought has moved in Lighthizer’s direction. Even economists acknowledge that the shrinking U.S. manufacturing base, partly due to trade, has had collateral costs: “deaths of despair” in communities devastated by lost factory jobs, and dependence on China for products vital to economic and military security…

Lighthizer agrees that deficits reflect savings differentials, but not that they are natural. Rather, they result from other countries’ policies that suppress consumption and subsidize exports. An example: Germany’s early-2000s labor reforms which, along with the adoption of the euro, suppressed German wages and rewarded exporters. An important influence is Peking University finance professor Michael Pettis, who has written extensively on how China’s suppression of consumption dictates that it run a trade surplus and other countries run deficits. As deficit countries lose incomes, they must either accept higher unemployment or increase debt to replace lost spending power. Mainstream economists increasingly agree China’s surpluses are harmful. “When the global market is flooded by artificially cheap Chinese products, the viability of American and other foreign firms is put into question,” U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, an economist, said in Beijing last month… Lighthizer said a surplus results from a range of policies such as the banking system, the labor system and industrial policy. That’s why he backs Trump’s proposed universal tariff of 10% plus a higher tariff on China, not as a bargaining chip over a specific trade barrier, but to eliminate the U.S.’s structural deficit.

Lighthizer hardly gets the credit he deserves. In fifty years when we can take a more dispassionate view of what’s happening today, I’m inclined to believe that Lighthizer’s role in recalibrating the global views on China will be acknowledged.