One of the big macroeconomic debates after the pandemic has been on the trajectory of inflation. The team persistent, led by Larry Summers and Co., worried that the persistence of the extraordinary monetary and fiscal policies, long after the pandemic subsided, may have unleased inflationary forces that cannot be brought down without a recession. The team transitory, led by Joseph Stiglitz and Co., argued that the inflationary episode was due to negative supply shocks from the pandemic and the Ukraine war and would recede once the shocks subside.

As with everything in economics, it’s difficult to establish who’s turned out right conclusively. There are arguments in favour of both. The Economist has a good summary here that also points to a study by researchers at Allianz.

They conclude that the Fed played a vital role. About 20% of the disinflation, in their analysis, can be chalked up to the power of monetary tightening in restraining demand. They attribute another 25% to anchored inflation expectations, or the belief that the Fed would not let inflation spiral out of control—a belief crucially reinforced by its tough tightening. The final 55%, they find, owes to the healing of supply chains.

I’m inclined to agree with the Allianz conclusion. Even if the surge in inflation was completely driven by supply shocks, given the massive accompanying fiscal and monetary stimuluses, I don’t think inflation would have subsided on its own. In fact, it can be argued that inflation could have been lower if the monetary authorities acted earlier than they did.

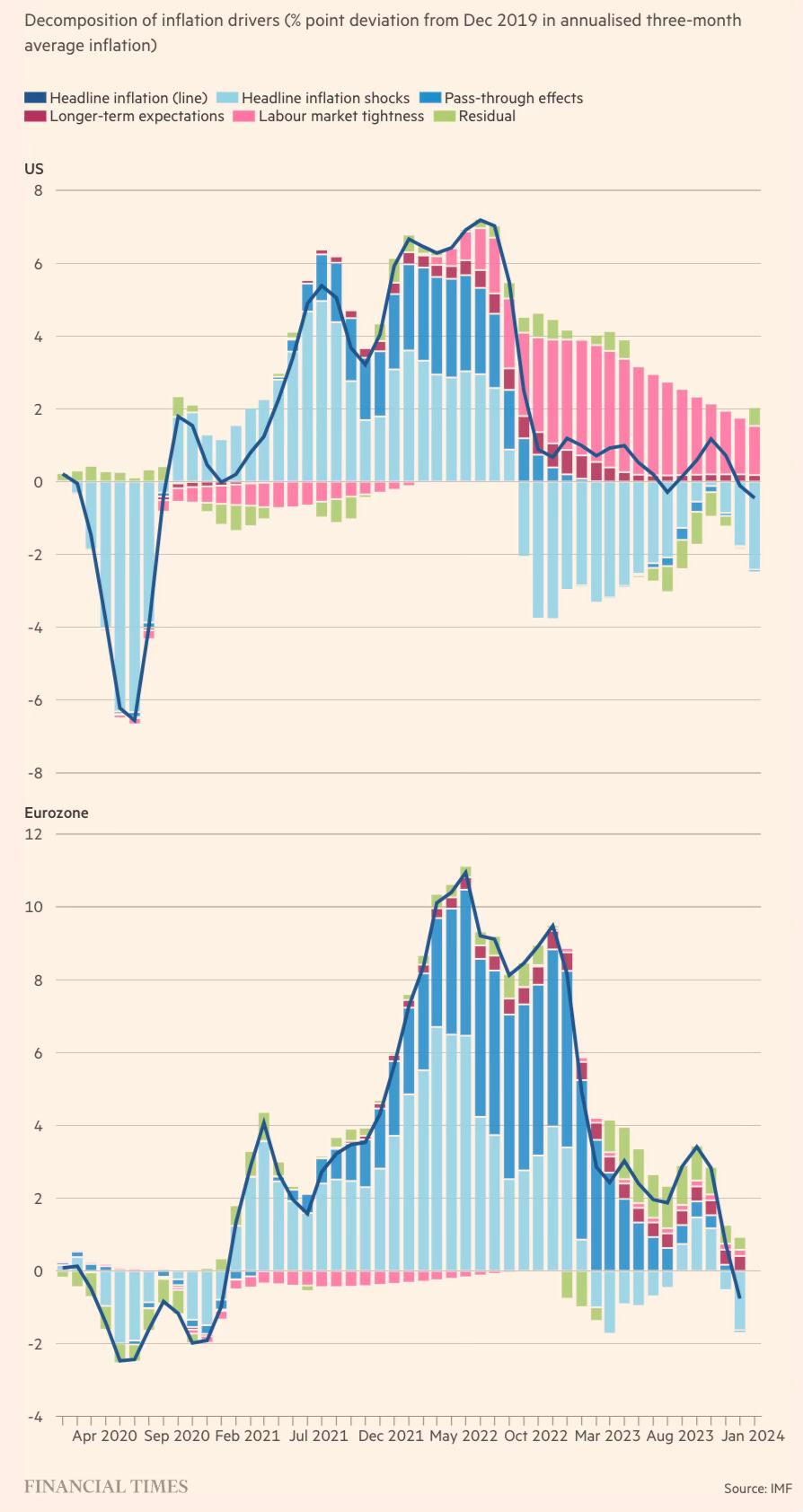

The latest World Economic Outlook has some useful pointers about the sources of inflation across advanced countries in the 2020-24 period. Martin Wolf has the same graphics that disaggregate the drivers of inflation in the US and the Eurozone.

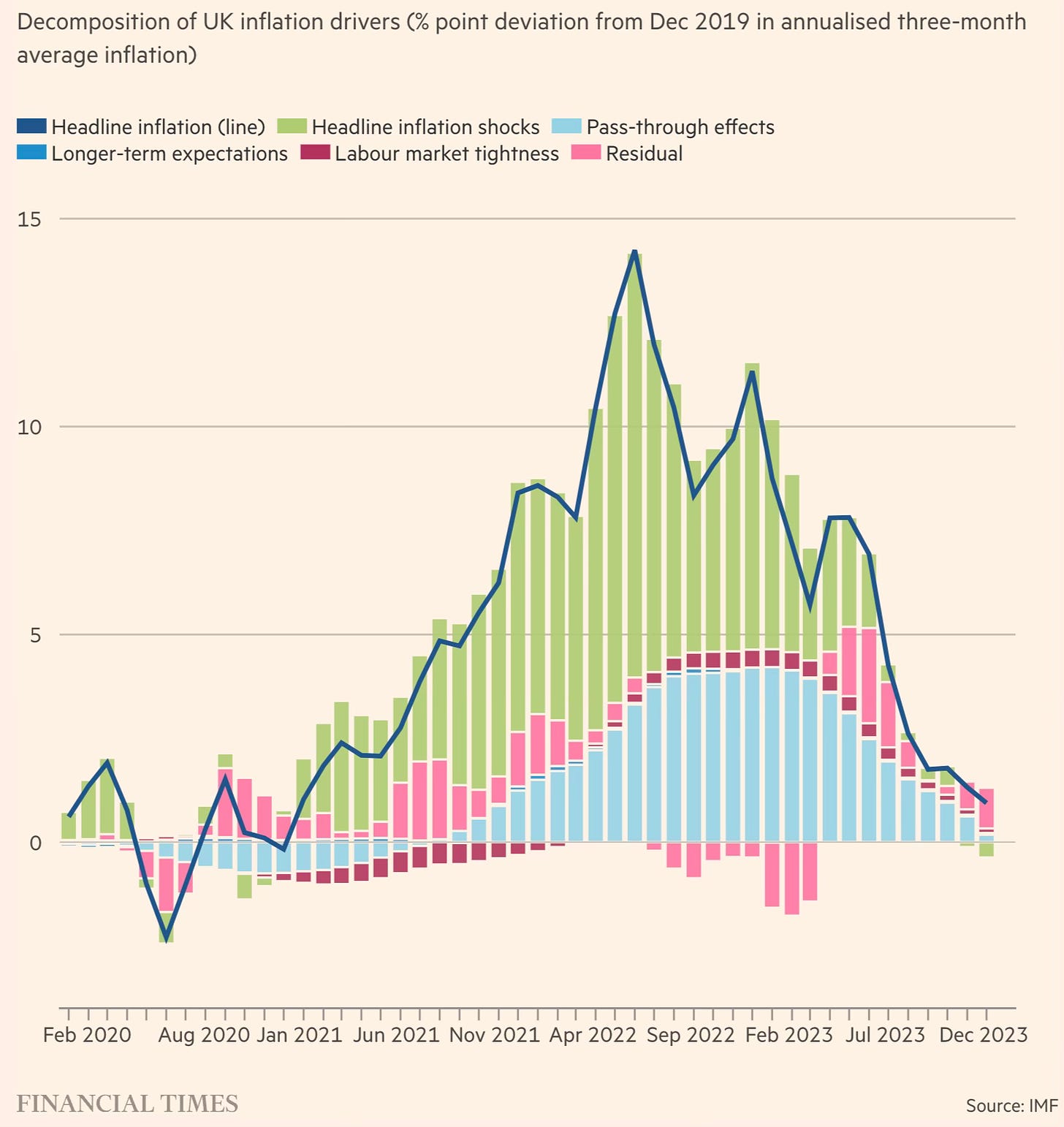

This disaggregates inflation drivers in the UK.

It’s clear that at least from early 2021 till about the end of 2022, all the advanced countries were deeply impacted by the supply shocks and the pass-through effects. These effects were more pronounced in Europe given its direct dependence on Russia for its energy needs. But the one standout feature is the rapid recession of the supply shocks and pass-through effects once the episodes themselves (the pandemic and the war) subsided. The difference though is that in the US a labour market tightness emerged to sustain inflation. The WEO writes,

The rapid fading of pass-through from past relative price movements––in particular from energy price shocks––has played a larger role in the euro area and the United Kingdom than in the United States in reducing core inflation. In the United States, labor market tightness and, more broadly, strong macroeconomic conditions, which partly reflect the effects of earlier fiscal stimulus as well as strong private consumption, are the main source of remaining upward pressure on underlying inflation. In the United Kingdom, labor market tightness predating the pandemic may partly explain why inflation has been higher than in the US or euro area following the onset of the pandemic.

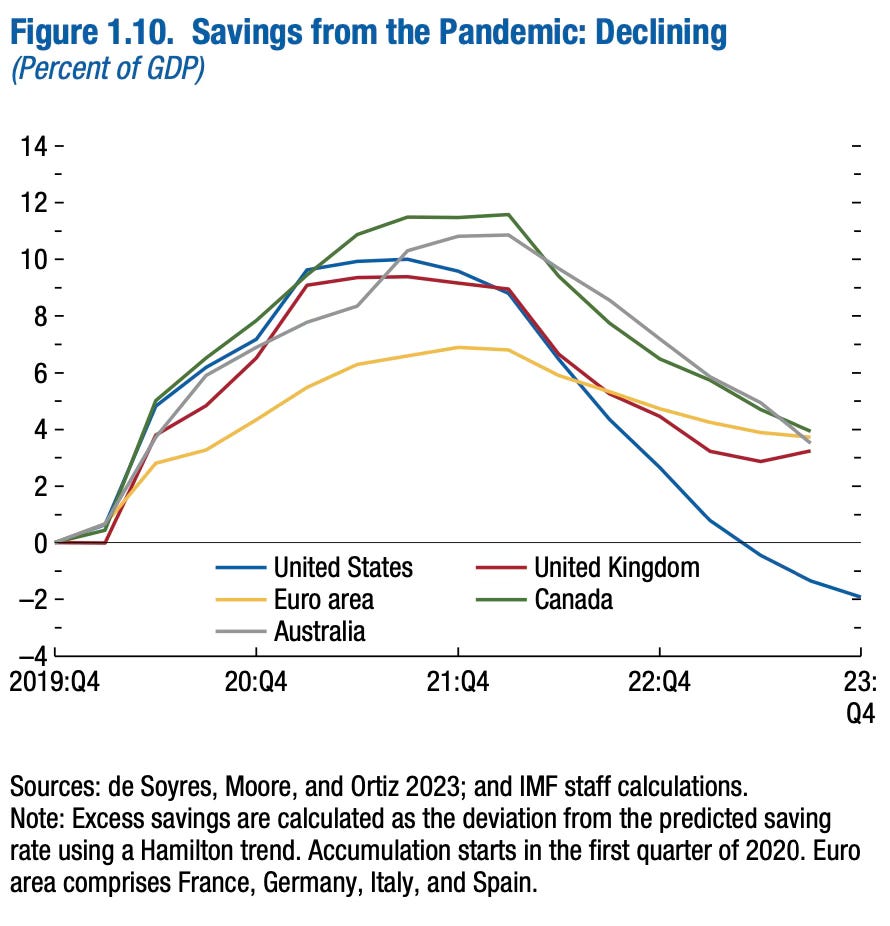

The WEO also points to the normalisation/depletion of the excess savings accumulated during the pandemic.

As the WEO writes, the massive fiscal stimulus especially by way of direct transfers coupled with the booming stock markets, and associated strong private consumption has been an important factor in keeping the labour market tight and inflation elevated in the US. While the supply shocks have long receded, the lagged effects of this stimulus still linger.

But there have been two additional factors stimulating the economy and consumption in the US - the strong equity and housing markets and associated wealth effects, and the investment boom (including government stimulus) in green technologies, semiconductor chip manufacturing, and AI. The investment boom is in its early phase and will play out over at least this decade, if not longer. There will be associated productivity improvements.

All this means that it’s unlikely that the US inflation will fall back to 2% anytime soon. In fact, as I have blogged earlier, the return to normalcy in inflation might not mean a return to the pre-pandemic 2% rate but a slightly higher band, perhaps 2.5%-3.5%. There has been a regime shift in inflation. If this is true, the US economy is far closer to its new normal inflation regime than the Fed imagines.

No comments:

Post a Comment