Following the debates on carbon emission reductions, one could easily come away with the feeling that the main issue in question was a technical challenge, how to find the resources to finance green investments. These debates skirt the important deeply contentious practical issues of who’ll bear the costs of climate transition and how to overcome the political economy opposition.

This is highlighted in the ongoing US Presidential elections where the Republican candidate is openly campaigning for expanding fossil fuel use. Here’s a snippet from a NYT report about one of President Trump’s fundraising dinners.

Mr. Trump repeated his public promises to delete Mr. Biden’s pollution controls, telling the attendees that they should donate heavily to help him beat Mr. Biden because his policies would help their industries… Mr. McKenna said the former president’s appeal to the fossil fuel industry could be summed up as: “Look, you want me to win. You might not even like me, but your other choice is four more years of these guys,” referring to the Biden administration… Karoline Leavitt, a spokeswoman for the Trump campaign, did not address the specifics of what Mr. Trump was described as saying at the dinner. In a statement, she attacked President Biden as controlled “by environmental extremists who are trying to implement the most radical energy agenda in history and force Americans to purchase electric vehicles they can’t afford,” and that Mr. Trump is “supported by people who share his vision of American energy dominance to protect our national security and bring down the cost of living for all Americans.”… the former president told executives that he was determined to squash what he considered anti-business policies, and that the oil industry should therefore want him to win and should raise $1 billion to ensure his success. He told the executives that the amount of money they would save in taxes and legal expenses after he repealed regulations would more than cover a billion dollar contribution, the people said.

The political challenges are mirrored on the economic/market side.

The much-hyped transition to Electric Vehicles has run into rough weather even before it has begun. EV car demand appears to have hit a plateau and sales have slowed everywhere (except China). Manufacturers have been cutting prices frantically in a race that has slashed margins. Competition from the heavily subsidised EV exports from China has only compounded matters.

Inadequate charging infrastructure and more importantly high prices have meant that the demand for EVs has peaked, at least for now, quickly. The limits to rapid energy transition in automobiles have been exposed.

The result has been a spike in the demand for hybrids, which were only till recently considered a needless distraction.

Global carmakers are stepping up their investment in hybrid technologies as consumers’ growing wariness over fully electric vehicles forces the industry to rapidly shift gear, according to top executives… Electric car sales growth slowed in the US and Europe last year, prompting carmakers to offer discounts… For many carmakers, the slower switch is allowing them to continue to squeeze profits from traditional engines while also providing more financial firepower to develop electric vehicle technology.

The lesson from the example of EV is important. Energy transitions cannot be squeezed into the short time frames we want. Legacy investments cannot be junked without someone bearing its costs. The green alternatives must become affordable enough for the customers to switch. These alternatives must develop the ecosystem required to become the new norm. Finally, the political economy of such transitions needs to be considered.

If the developed economies with their much higher levels of incomes cannot afford to rapidly and directly substitute away from ICE to EV, then it’s both unfair and unrealistic to expect the developing economies to undertake the ambitious energy transitions that are being thrust on them.

The EVs are only the latest example. The transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy generation is another example. Just as hybrids might be a practical intermediate stage in the green transition, substitution towards natural gas should be seen as a step in the right direction and encouraged.

Consider a few other data points. As this FT article shows, while climate change mitigation may be the professed policy of the US and other governments, there’s an increasing dichotomy between the policies and outcomes.

Biden made tackling climate change a central priority for his administration and vowed to crack down on America’s oil and gas industry. He has brought in environmental rules that range from endangered species protections and a clampdown on methane leaks to restrictions on offshore leasing and the suspension of new licences for the multibillion-dollar terminals needed to liquefy American gas and ship it abroad… On his first day in office he signed an order revoking a crucial permit for the Keystone XL pipeline — in effect killing an $8bn project designed to shuttle oil from Alberta, Canada, to Gulf Coast refineries. More policies followed: a temporary suspension of drilling on public lands; freezing and then scrapping leases in an Arctic wildlife refuge; and introducing a charge on methane leaks, the country’s first nationwide fee on a greenhouse gas, to the delight of environmental groups…

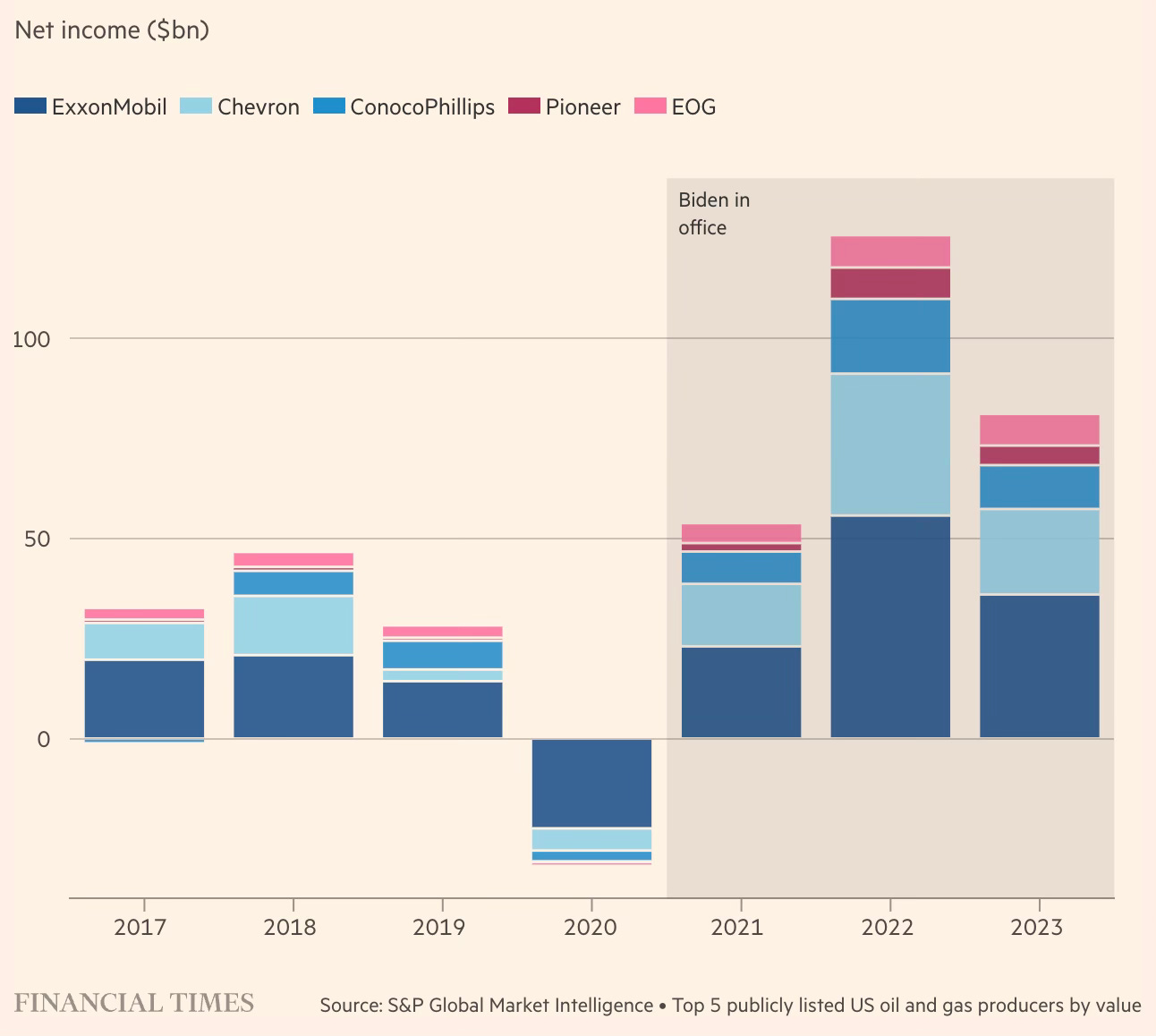

America’s oil and gas industry has flourished under Biden. At more than 13mn b/d, production is at record levels, exports of American hydrocarbons have surged and the scale of annual profits has been unprecedented — largely driven by a jump in commodity prices following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Investors in the industry have reaped rewards too, as cash-rich producers showered them with returns. Shares in ExxonMobil have more than doubled since Biden took office and, emboldened by high prices, the industry has also splurged on mergers and acquisitions, making some of the biggest deals in decades…. As a result of higher prices, 2022 was the most profitable year on record for publicly traded US oil companies.

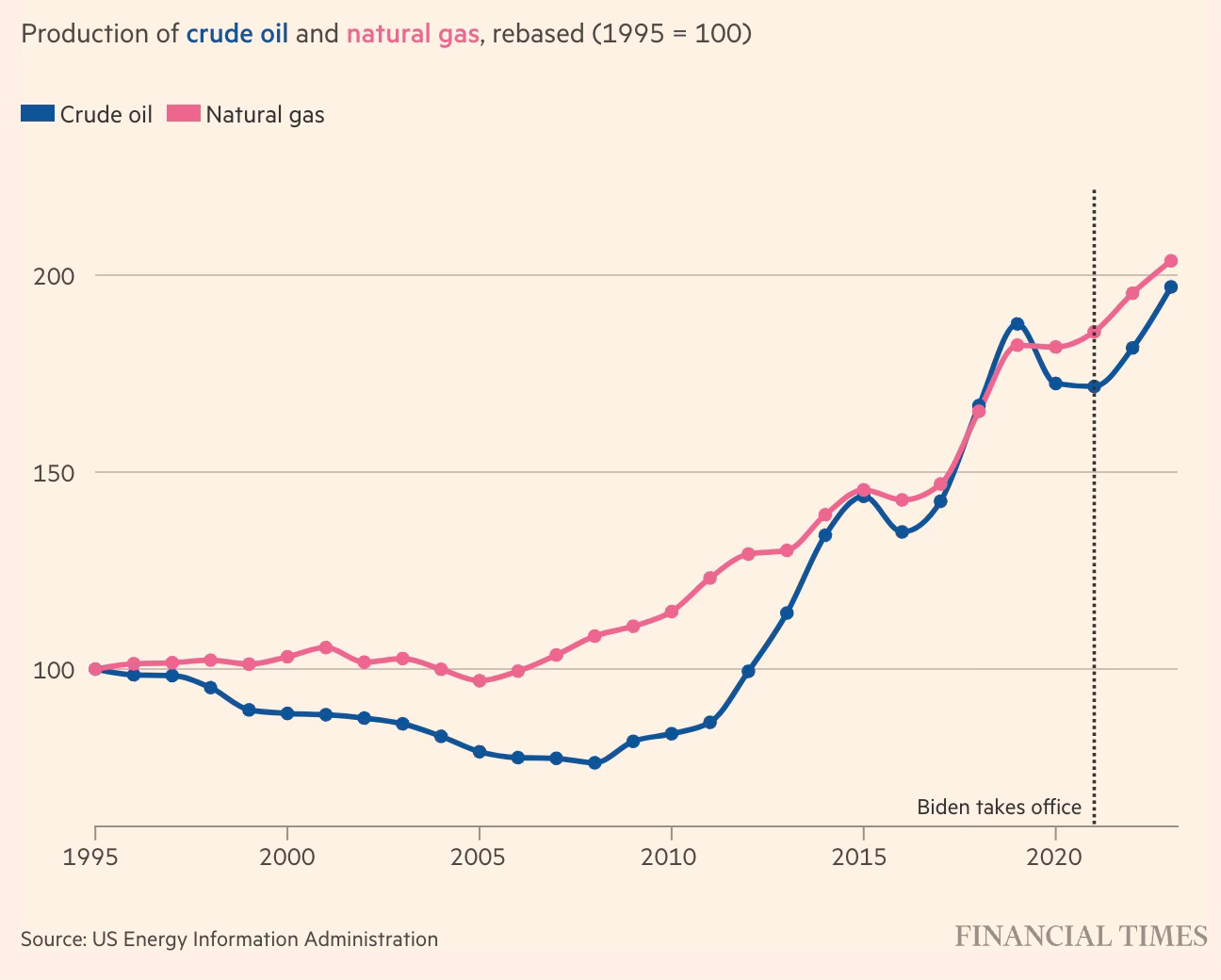

The first graphic informs that the US oil and gas production has been consistently rising since 2010 and is now at record levels.

The second graph shows that contrary to a discount on fossil fuels, the profits of the biggest oil companies have risen sharply.

There might be a problem with the framing of the technical challenge of mobilising finances for the green transition.

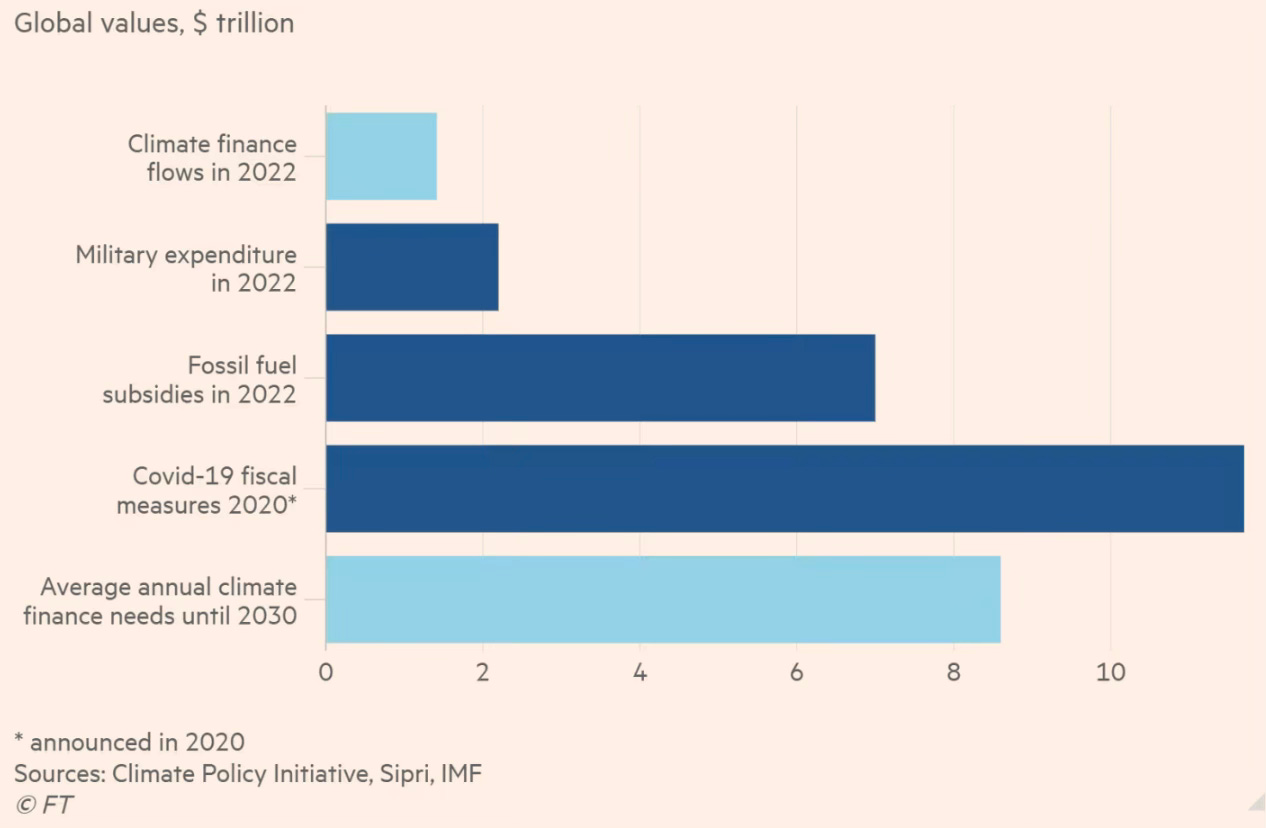

Two graphics below puts the climate finance mobilisation challenge in perspective. The first show the extent of climate finance currently available and how it compares with other expenditures and fossil fuel subsidies

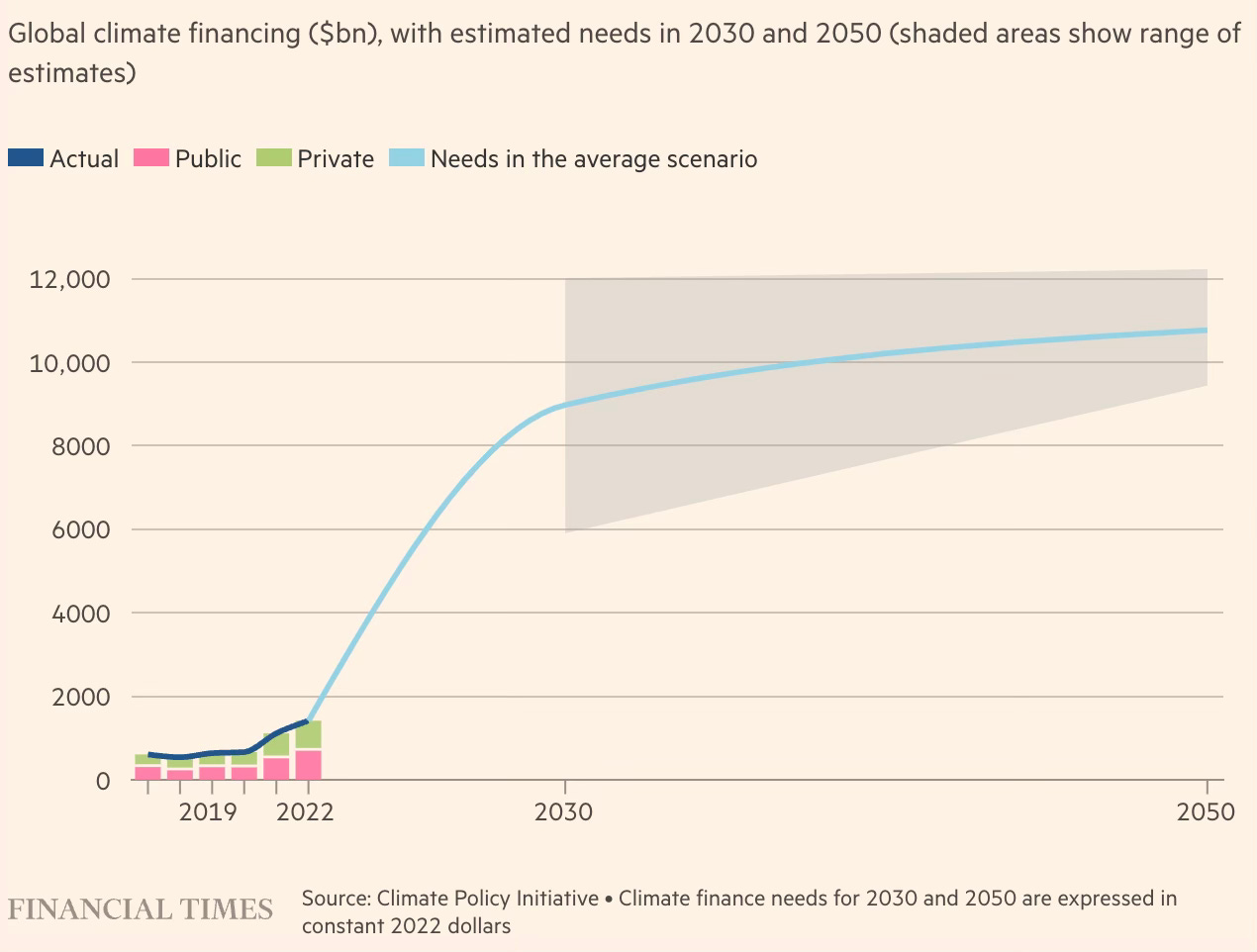

The second shows the requirement over the coming years.

The requirement estimated is staggering.

I’ll be very surprised if anything like the amounts indicated in the graphs can come in the foreseeable future. In this report, we highlighted the near impossibility of mobilising financing of this scale. I’m also not sure whether we even need such amounts. It may therefore be useful to revisit some of these numbers which may have emerged through high-level assessments of the kinds that consultants make.

It’s perhaps the case that at least some of the proponents of these numbers also see these numbers as a strategy to shock and awe governments to focus on resource mobilisation. But the size of the numbers being thrown around may also have made any meaningful engagement impossible. If a gun is placed on your head and you are asked to run 100 metres within 10 seconds, you are more likely to give up than even try the race! The sheer impossibility of the numbers in estimates like that in the Stern-Songwe report may have perversely enough turned off serious policymakers from even attempting to mobilise them.

No comments:

Post a Comment