The FT has three long reads assessing the programs initiated in 2019 in the name of “levelling up” to reduce regional inequalities. It included four central government regeneration programs for a five year period till 2025-26 with a total allocation of £10.4bn and covering mostly some form of construction.

The problems in the programs' design, implementation, and outcomes have strong resonance with similar central government programs in India like Smart Cities and AMRUT, for example.

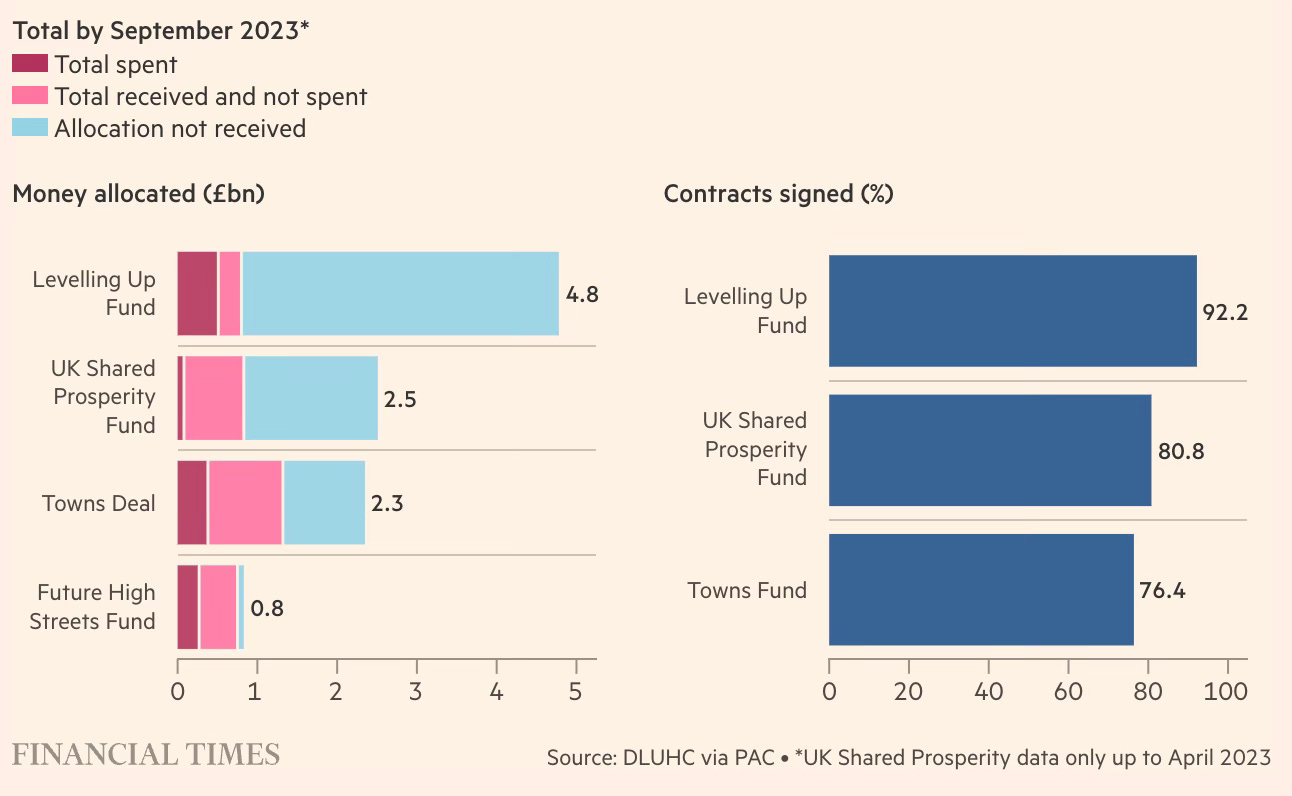

Data from nearly four years of implementation show that a disproportionately low share of the allocation has been released and a negligible share has been spent.

The programs have struggled with several problems.

Parliament’s public accounts committee concluded in a recent inquiry into the three main funds that it had seen “no compelling examples” of delivery to date. The committee’s Labour chair, Dame Meg Hillier, describes them as “a sticking plaster” over the huge reductions made to local government funding since 2010, with comparatively steady income streams from government grants and council taxes partly replaced with “a real top-down” approach. Local authorities complain of delays, moving goalposts, unachievable spending deadlines, costly bidding processes and opacity and unfairness in the way the cash was allocated. Higher inflation over the past two years has also pushed up construction costs, eroding the value of disbursements… half of the projects for which funds have been awarded have only just started being developed…

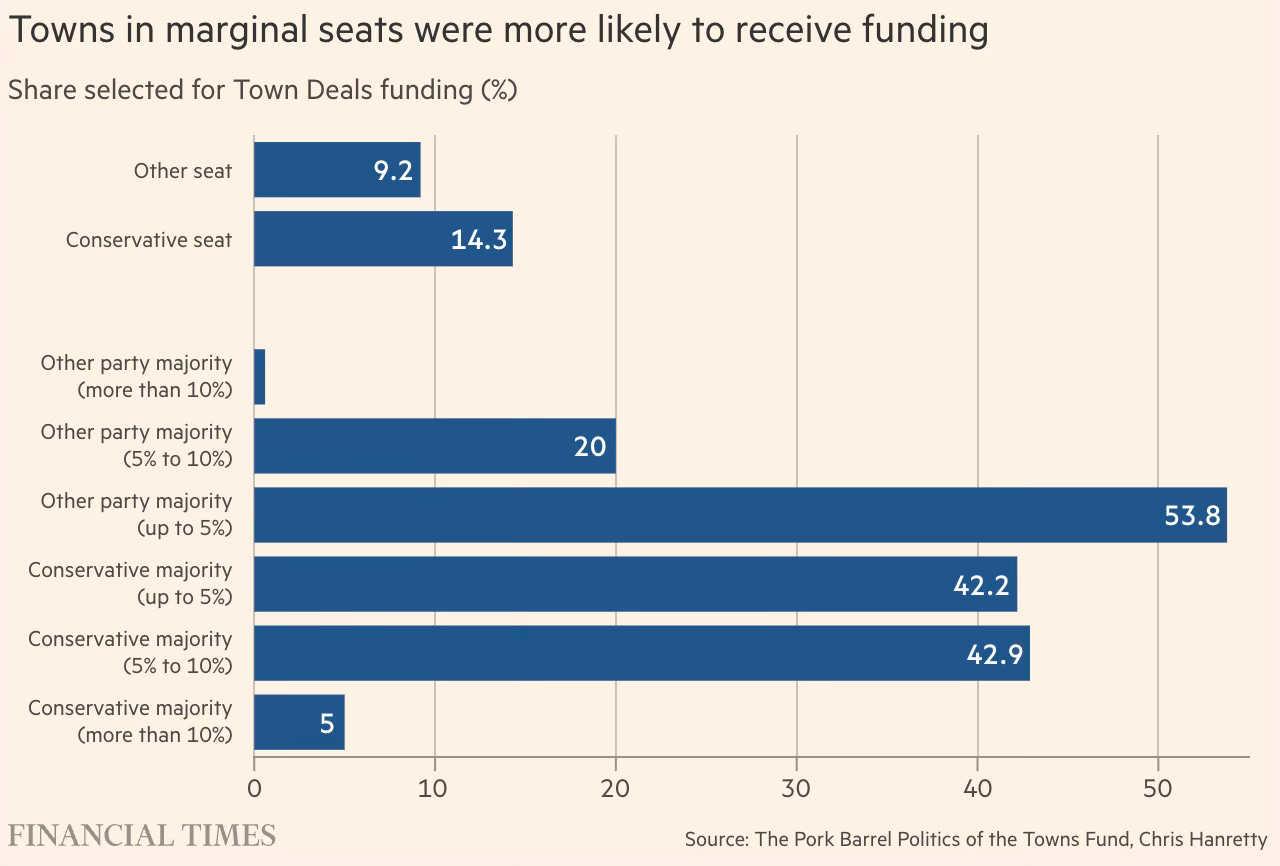

The funds were mired in controversy from day one. The first such pot, the £3.6bn Towns Fund, was launched by Johnson shortly before the 2019 election. Ministers selected 101 towns across England for one-off regeneration cash. A remarkably close correlation with Conservative electoral targets was quickly apparent, including some areas — such as Cheadle, a leafy marginal seat on the edge of Cheshire — with relatively low levels of deprivation. A public accounts committee report in 2020 found that the allocations had not been impartial…

(For the Levelling Up Fund) local authorities were required to draw up detailed bids for cash, including for transport, culture and regeneration projects. One council official in a deprived northern area compares the core document for their first unsuccessful bid to a “dissertation”, noting that the submission ran to more than 30,000 words without appendices and related reports. Such analysis is often beyond the capability of councils whose economic development teams have been whittled away by years of centrally imposed budget cuts. As a result, they have tended to hire consultants to draw up bids at an average cost of up to £30,000, according to the Local Government Association…

The Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) “had to assess multiple bids within a short timeframe”. “It could not do so as quickly as planned, and subsequent delays in making decisions on successful bids meant that announcements about funding allocations were made later than planned,” concluded the NAO… A further problem emerged in 2022, as inflation began eating into projects that had been costed months earlier. In Bury, the council secured £20mn each for two regeneration projects with the intention of providing the remainder of the projects’ expected cost itself. “But then you get inflation and costs and all of a sudden your £40mn project becomes a £50mn project and you don’t necessarily have that [extra] £10mn,” says O’Brien…

Interestingly, the problems mentioned in the context of these UK programs are present in India too.

Another aspect of such programs is the small amount each locality gets over a short period, which is inadequate to create anything transformative and with a long-term plan.

“The theory of levelling up should be good,” says Hopgood. But the money has ended up sprinkled across the country, she adds. “They might as well have called it ‘spreading it out’.”… “At the moment you can’t engage in investment in longer-term capital projects, and projects that are more transformational, because you have to get all the money out the door in 24 months, so unless it’s ‘shovel ready’ it’s a non starter,” he says. “Sometimes the things that make the difference and have value for money are things that are planned and delivered on a longer fuse.”

All this raises questions on the strategy of packaging all fiscal transfers from federal governments to sub-national entities in the form of national programs. Such transfers are appropriate in those cases where the objectives and means to achieve them are the same across the country. But it’s inappropriate for projects that require context-specific design or seek transformational area-wide impacts.

The latter kind of projects generally entail a comprehensive plan with multiple components, significant resources, and long-drawn implementation. They will involve local consultations, plan preparation, dovetailing resources from multiple sources including debt, and coordination among several stakeholders. Most importantly they require local ownership. They are not amenable to traditional programmatic funding, even with flexibility.

A more appropriate strategy would be to make block transfers tied to the transformation plan for implementing some components. The entities should be allowed the freedom to leverage this money in whatever manner it deems fit to mobilise the additional funding required for the transformation plan. An even more effective approach would be to increase devolutions or enhance the local government’s powers to raise additional revenues.

The UK levelling-up programs include devolution of funds.

The “common sense” approach that has emerged more recently is reflected in the beefed-up devolution deals granted to Greater Manchester and the West Midlands last year, he adds, featuring longer-term and more flexible devolved pots. These provide a mixture of revenue and capital, avoiding the scenario in which funding is advanced for construction of a building or facility that the council cannot then afford to run, says Hawksbee… More recently, the government has also allowed some local areas to roll together separate bids from different funds into one more coherent programme, working particularly closely with councils such as Blackpool.

Also this.

The government has struck devolution deals with a number of areas including North of Tyne, West Yorkshire, East Midlands and York & North Yorkshire. This means that nine out of 10 people in northern England are now covered by a devolution deal, while in the whole of England 64 per cent of the population lives under a devolved authority — up from 41 per cent two years ago — with powers over areas such as investment, transport and adult education.

This also raises the issue of leveraging budget transfers to mobilise debt that can supplement the scarce fiscal resources to finance large investments.

For example, the ongoing central or state government schemes in India in urban or rural areas can finance large projects in one city, village, or region. They require large financing upfront.

The local or state government must find resources from somewhere to finance such investments. It’s highly unlikely that they can mobilise the kind of fiscal resources required from internal revenues alone. The only way out would be to use debt to mobilise the upfront resources required to make these investments and repay from future budget transfers or revenues.

However, the prevailing budget accounting in India treats debts that are serviced partially or fully from budget transfers as direct liabilities of the government. These liabilities get deducted from the open market borrowings (OMBs) permitted to the state government under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act. State governments are loath to give up their cheaper OMBs for the more expensive project borrowings from banks or through bonds.

There’s therefore a compelling case to allow for such borrowings for certain kinds of projects without deducting them from the state’s FRBM limits. These borrowings can be mandated to be done through special purpose vehicles and shall effectively be off-balance sheet debts of the state government. There’s every risk of this provision being misused by some states. It’s therefore important to also place limits on the extent of such off-balance sheet borrowings permissible.

1 comment:

A better long term solution in Indian context would be to build local government level revenue streams with a US type federal plus state plus city level tax system ? Or even a three level gst with a component for city as well ?

Post a Comment