The case for free trade has been an article of faith in orthodox economics. It endures despite little evidence from the whole history of national economic growth. But notwithstanding orthodoxy, there has been renewed interest in industrial policy and trade restrictions in recent times.

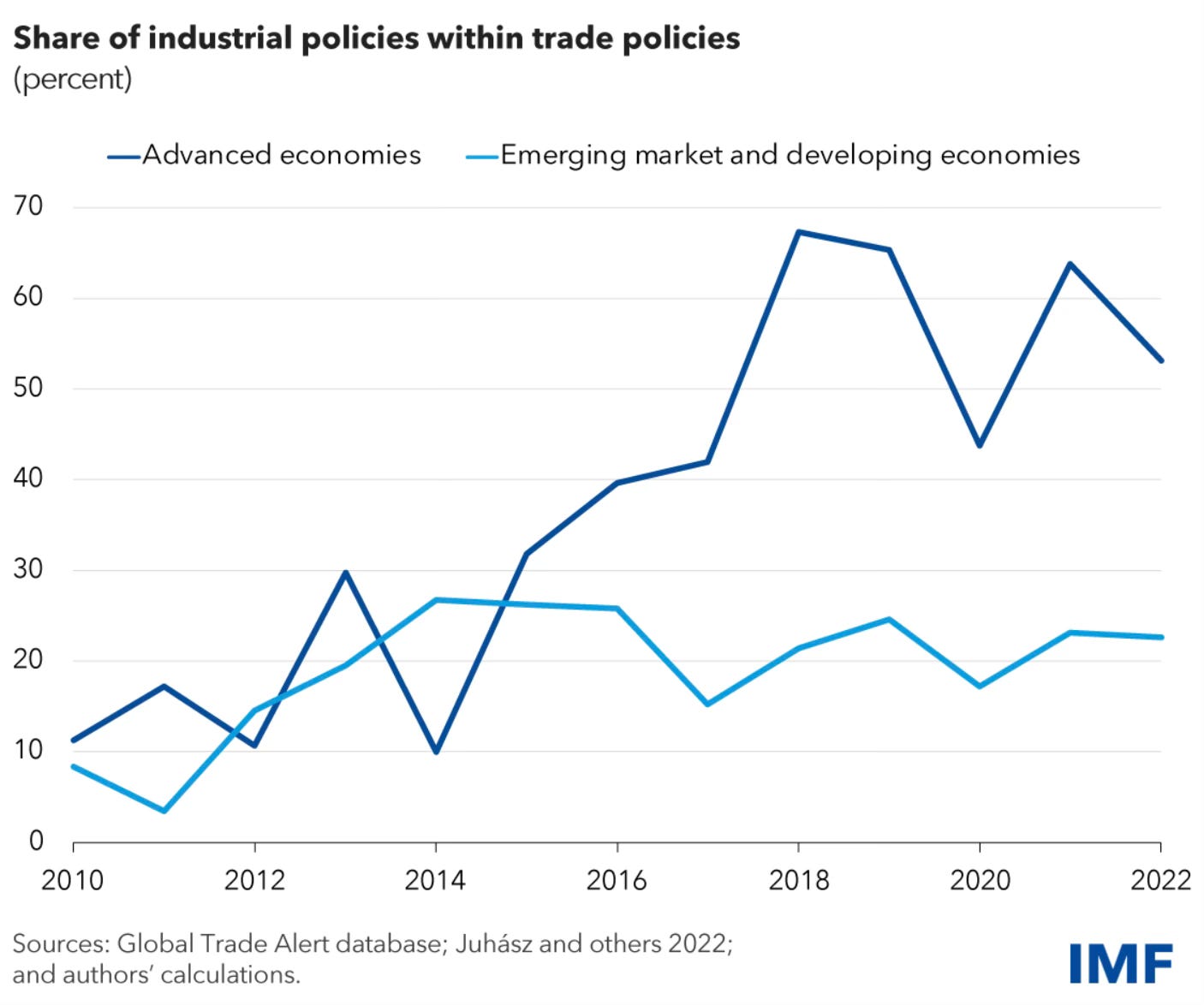

Gillian Tett points to a recent IMF report that describes no less than 2500 industrial policy actions globally in 2023 alone, and developing and developed countries racked up 7000 and 6000 industrial policy actions in the 2009-22 period. And industrial policies have spiked in developed countries, spurred by the threat from cheap Chinese imports.

The IMF report says that “well-designed fiscal policies that support innovation and technology diffusion more broadly, with an emphasis on fundamental research that forms the basis of applied innovation, can lead to higher growth across countries and accelerate the transition to a greener and more digital economy.”

Tett also draws attention to a paper written by IMF economists Reda Cherif and Fuad Hasanov on the return of industrial policy

There is an important difference between policies that try to create growth by shielding domestic companies from foreign competition and those which help those companies compete more effectively on the world stage. The former “import substitution” strategy was pursued by many developing countries in recent years, including India. It is also the variant favoured by Trump and the one being considered by some European politicians, for instance in the case of Chinese solar panels. But it is this latter approach that has given industrial policy a bad name. On the basis of copious data, Cherif and Hasanov argue that import substitution models undermine growth in the long term since they create excessively coddled, inefficient industries. By contrast, the second variant of industrial policy aims instead to make industries more competitive externally in an export-oriented model, while worrying less about imports. This approach is what drove the east Asian miracle, and is what creates sustained growth, the data suggests. The difference in approach is embodied by the contrasting fortunes of Malaysian automaker Proton car and South Korea’s Hyundai. The former was developed amid import substitution policies, and never soared; the latter flourished on the back of an export-oriented strategy.

Cherif and Hasanov distinguish true industrial policy from a Technology and Innovation Policy (TIP) and argue that, unlike others, the East Asian economies pursued TIP.

Although they were not hit with severe negative shocks or possessed some intrinsic characteristics for success, their high sustained growth was the outcome of the implementation of an ambitious technology and innovation policy over decades that kept adapting to changing conditions and moving to the next level of sophistication. The state set ambitious goals, managed to adapt fast, and imposed accountability for its support to industries and firms. We argue that first, TIP was based on the state intervention to facilitate the move of domestic firms into sophisticated sectors beyond the existing comparative advantage. Second, export orientation since the onset played a key role in sustaining competitive pressure and pushing firms to innovate. This strategy contrasts with import substitution industrialization strategies, prevalent until the late 1980s among developing economies, that led to inefficiencies, lack of innovation, and persistent dependence on key imported inputs. Finally, the discipline of the market and accountability were enforced in a strict manner… The more a country was willing to leap technologically beyond comparative advantage and the more this technology was produced by domestic firms, the higher the chances were to sustain high growth…

We argue that TIP offers broad concepts of a growth strategy, the modalities (e.g., tools) of which are yet to be defined… In terms of the role of state, TIP is the exact opposite of centralized planning, as it favors more competition and autonomy of the private sector, not less. The role of the state to intervene is to correct market failures where they exist and enforce a strict market discipline. As such, it is the exact opposite of indefinite support for under-performing, under-innovating and rent-seeking firms. We are not arguing that TIP is easy to pursue or that there is a cookbook recipe. For example, how to select sectors or enforce a strict market discipline is still an uncharted territory… TIP is not in opposition to the standard recipe of macro-stability, improving institutions and business environment, or investing in infrastructure and human capital. All these ingredients are necessary, but not necessarily sufficient for high sustained growth. Through the lens of TIP, policymakers can set clearer priorities for their growth strategies, and we argue that higher and more sustained growth is more probable. The Asian Miracles correspond to the most ambitious version of TIP, which led them from low-income to high-income status in a couple of generations. But there is a spectrum of possibilities depending on domestic and external conditions and how ambitious the authorities are and how willing they are to implement TIP.

Cherif and Hasanov have an updated version of their paper here. They argue that industrial policies failed in the past because the “true one was barely tried… among developing economies, very few pursued an export-oriented industrialization policy on a large scale as it was the case in the Asian miracles.” Cherif and Hasanov merely confirm what Joe Studwell has brilliantly illustrated here.

The pursuit of TIP is hard. Consider the example of India’s automobile industry which is facing the transition from internal combustion engines to greener alternatives. I came across this article by Ajai Srivastava who uses the examples of India and Australia to highlight the points made by Cherif and Hasanov.

The Indian auto sector took a leap in the early 1980s with a JV between the Indian Maruti Udyog Limited and the Japanese Suzuki Corporation. Japanese technology and India’s expertise in casting, forging, and fabrication enhanced the domestic auto sector’s productivity by 250 per cent over the next 20 years and set it on a high growth path. Subsequently, three government decisions shaped the industry: The imposition of high import tariffs ranging from 70-125 per cent on completely built cars and motorcycles, but a low 7.5-10 per cent tariff on parts and components to allow the import of inputs; not cutting tariffs under the free-trade agreements or FTAs; and allowing up to 100 per cent foreign direct investment through the automatic route. While high import tariffs sheltered firms operating in India from external competition, the presence of many top global firms making cars in India ensured intense internal competition… About 70 per cent of India’s passenger cars are made by companies controlled by foreign firms like Suzuki, Hyundai, Kia, Toyota, Honda, Ford, Skoda, Renault, Nissan, and Mercedes. Key Indian firms are Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra…

Many experts question the rationale of high tariffs. The example of the Australian auto industry, however, suggests an unwelcome outcome of tariff cuts. In 1987, Australia produced 89 per cent of the cars it used, protected by a high 45 per cent import duty. However, as Australia gradually reduced these tariffs, the proportion of locally produced vehicles decreased. Today, with import tariffs at just 5 per cent, Australia imports nearly all of its cars. Major manufacturers like Nissan, Ford, General Motors, Toyota, and Mitsubishi, which once produced vehicles in Australia, have since closed their operations there.

While industrial and trade policy helped India create a strong automobile manufacturing base, it could not make it globally competitive or innovative. This meant an automobile ecosystem primarily serving the local market and that too by foreign manufacturers. There was limited incentive to innovate, expand the technology frontier, become globally competitive, develop domestic brands, and serve export markets. It’s striking that Indian corporates have failed to leverage their massive domestic market to develop globally competitive brands in any major consumption goods and services.

As the article informs, there’s a danger that India might be committing the same mistake with its policies on electric vehicles. In particular, there’s a strong risk that the domestic EV industry will depend on Chinese components and be captured by foreign manufacturers. I blogged earlier on it here.

The example of Australia’s auto industry mirrors manufacturing in general across many developed countries, especially the US. The emergence of business models that prioritised outsourcing and services over manufacturing and the attractiveness of cheap imports, coupled with an ideology that scorned industrial policy and trade restrictions, meant that these countries allowed heavily subsidised Chinese exports to destroy their local manufacturing base.

In this context, here’s my summary of the case for a heterodox industrial and trade policy.

Certain industries are critical in the evolution of any country’s manufacturing capabilities - textiles, footwear, steel, consumer electronics, automobiles, pharmaceuticals and chemicals, etc. They catalyse manufacturing ecosystems with productivity spillovers that generate good jobs in large numbers. These sectors have backward and forward linkages that allow economies to start with less skilled activities and move up the value chain of skill and productivity. The North East Asian and Chinese economic miracle have been built on these sectors.

The standard macroeconomic toolkits of stable and predictable policies, enabling business environment, and investments in human capital and infrastructure are insufficient to develop dynamic and competitive manufacturing ecosystems. Instead, the realisation of these beneficial effects from manufacturing depends also on the industry structure and the nature of the demand.

So for example, a textile or electronics industry dominated by small and medium firms and manufacturing for a lower middle-income country's domestic market is unlikely to harvest the full gains from manufacturing. They are unlikely to generate the market discipline, competition, and ecosystem required to increase productivity and move up the value chain. They are similarly unlikely to have the incentives to innovate and invest in new technologies and push the frontier by moving up the value chain. Scale and export competition are critical.

Scale can be achieved either by a large multinational company or being a contract manufacturer for large global brands. The East Asian economies generally took the latter route in their initial years. It also meant that the firms had to maintain high competitiveness in productivity and quality. This created a solid foundation for the growth of the manufacturing sector in the region. They also benefited from favourable geopolitics, trade liberalisation, and globalisation.

Trade liberalisation and globalisation led to global value chains (GVCs) that integrated businesses and industries across borders. These value chains expanded in breadth and depth, resulting in greater economic integration of whole economies into the GVC with all its beneficial effects.

In stark contrast, India struggled to create globally competitive manufacturing ecosystems at scale in any of these sectors and failed to integrate with GVCs. For a long time neither could India produce multinational companies nor attract large contract manufacturing firms. The resultant lack of competitiveness and scale meant that India’s manufacturing base was largely aimed at making for India. The domestic companies could not compete with foreign competitors in wide swathes of the economy. The premium and higher segments were captured by foreign brands, leaving the low-margin lower market segments to the local manufacturers.

Successive governments in India missed the opportunities to use industrial and trade policies like adjusting tariffs to move up the value chain, subsidies and concessions linked to export performance, joint ventures, technology transfers, local content requirements etc. Indian private sector failed to seize the opportunities to create world-class companies and brands and emulate their counterparts in East Asia. Their failure to invest in technology upgradation and innovation, manifest in their low R&D expenditures, must count as a singular failure of corporate India.

It can perhaps also be argued that India may not have had the economic bargaining power in the early years of liberalisation to pursue such policies. Besides, unlike the East Asian economies, the global economic orthodoxy and institutions like the IMF have generally had greater influence on India’s macroeconomic policies.

A marked shift in recent years has been the willingness to break out of the orthodoxy and exhibit greater commitment and diligence to pursue heterodox industrial and trade policies. It has certainly helped that the Indian economy is now larger and a major contributor to global economic growth, thereby dramatically increasing its bargaining power. Finally, the global concerns with excessive economic reliance on China and the escalating Cold War between the US and China have been tailwinds that favour the Indian economy.

This willingness to shun orthodoxy also owes to the economic and national security threat posed by Chinese imports and its dominance of sectors and critical manufacturing inputs. The tense border situation with China supplements the increasingly evident security risks posed by that country’s beggar-thy-neighbour economic policies. The refusal to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and stiff restrictions on Chinese imports and capital inflows must be viewed from this perspective.

However, given China’s current dominance in important industrial sectors, it would be foolish and impractical for any country to abruptly and significantly cut itself off from China in the short term. Any policy to reduce reliance on the Chinese economy can only be nuanced, gradual and calibrated. It’s like sailing on two boats or pursuing two conflicting goals.

In the short term, it’s prudent to continue trade with China and benefit from the several advantages of such engagement. However, the evolution of such trade must be continually observed and policies tweaked to steer its course away. It would involve prohibitions on certain strategic sectors, imposing barriers on certain imports and continually adjusting them, encouraging the development of domestic capabilities, and diversifying away from China. Its success or failure cannot be evaluated based on short-term trends in imports from China.

It will entail significant costs by hurting local firms and the economy. This must be seen as the cost of national security against China. Economic interest groups and commentators who wail at the so-called protectionist policies aimed primarily against China would do well to keep this perspective in mind.

It’s undeniable that the cheap Chinese imports are great on a purely short-term cost-benefit assessment. In areas like renewables and new technologies, the Chinese subsidies have done more to mainstream innovation and technology and reduce costs. But they have come at the cost of the destruction of domestic industries across the world and created a very risky dependence on China across manufacturing sectors. This trend cannot be allowed to continue.

But India’s biggest challenge will be its ability and discipline to pursue well-calibrated and dynamic industrial and trade policies of the export-promoting kind that the East Asian economies did. Can it ensure that these policies prioritise export competition over import substitution? How do we ensure that such policies do not get captured by private interest groups that prevent the changes and adaptation required to move up the value chain? Specifically, can it ensure that the protection of domestic producers does not become an end in itself?

India’s private sector and mainstream commentators will by and large stoutly oppose such policies. Opinion makers will describe such policies as protectionist and retrograde. The central government ministries have disparate interests and would be far less committed to a national security narrative. More importantly, they will struggle to internalise that perspective required for the single-minded pursuit of such policies. Finally, there’s also the deficiency of the state capability needed to pursue such dynamic policies effectively.

No comments:

Post a Comment