The GameStop (GME) episode shines attention again on some dark corners of finance.

In short, for no particular reason a struggling physical retailer of video games attracted the attention of a Reddit forum WallStreetBets with 2 million subscribers. Investors pile on to the stock driving it crazily upwards. Incidentally, the same stock was shorted by some hedge funds, and their short positions may even have encouraged some of the Redditers.

To give a scale of the trading bubble, the stock rise from $3.5 in August, 2020 to $18 on January 2, 2021 and then took off to touch $347.51 on January 27. The stock, with 69.7 million shares outstanding, generated short interest (or short positions due for delivery) of 71.2 million shares, and on January 22, 194 million shares were traded, which is over twelve times its average trading volume. At one point in time, more than 100% of GME stock was on loan.

This crazy run forced online brokerages like Robin Hood to restrict trading on GME and other bubble stocks as they ran out of funds to finance margin trades and faced pressure from their investors. Interestingly, it also put pressure on hedge funds with short positions on GME, with at least one, Melvin Capital, being forced into a rescue package from other investors.

There were at least four loops at work, each of which went beyond their useful limits.

One, short-sellers bet against the stock by borrowing shares and selling short options. Sample this from a brilliant article by Matt Levine (HT: Ananth),

When you short a stock, you borrow shares and sell them, promising to return them later. You have to pay a fee to borrow shares, you have to post collateral based on the value of the borrowed shares, and you (generally) have to return the shares you borrowed if the lender asks for them back. When the stock goes up a lot, short sellers start feeling “squeezed”: Their borrow costs go up, they have to post more collateral, and lenders might asking for their stock back. Some short sellers might have to capitulate, and they will close their positions by buying back stock. There is a feedback loop: The stock goes up, short sellers give up, they buy stock to surrender, and their buying pushes the stock up more.

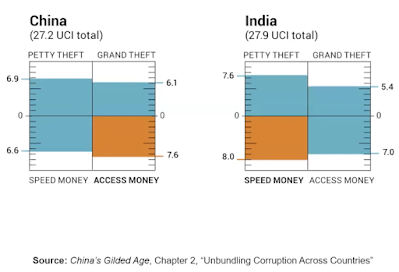

And this graphic.

Two, call buyers bet on the stock by buying options at a future strike price. This is great for small investors who want to bet on a rising stock. But if the stock price rises, the call option sellers are forced to buy more of the stock so as to cover their positions. This forces them into the 'gamma trap' of buying ever more quantities of the stock to limit their call losses.

Three, brokerages like Robin Hood and ETrade provide margin loans to traders, which allow the latter to trade multiples of their capital. The brokerages place the trader's stocks as collateral and borrow to finance margin loans. This trade starts to unravel when lenders to the brokerages step back as the collateral becomes evident as bubble stocks like GameStop. This, in turn, makes brokerages raise their margins. Such margin calls on short-sellers force them to borrow ever more (or sell part of their securities).

Finally, the brokerages themselves clear trades at the clearing houses (in the US, the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation for equities and the Options Clearing Corporation for options), which stand between two sides of a deal by managing the risk to the market if one side defaults (a trade takes upto two days to be settled). The brokerages need capital at hand not only to finance margin traders, but also to pay for the margin requirements imposed by clearing houses as insurance against trades on their platforms, so as to protect its members against market volatility. As bubble stocks inflate and volumes balloon, clearing houses raise the margin requirements from their members, brokerages and investment banks, to ensure that deals are honoured.

Finance 101 teaches us that the losses of option buyers are capped at their initial investment while potential profits are unlimited, and the losses of option sellers are unlimited. But a combination of short squeezes, gamma traps, and margin calls can destabilise entire markets.

In each case, perfectly fine strategies started to unwind. Two things were important - interconnectedness and speed of information (and misinformation) flows. Finance 101 considers both desirable attributes, in so far as they contribute to liquidity and efficiency in price discovery. But, as the GameStop episode shows, excessive liquidity and efficiency are dangerous.

A confluence of often unrelated factors like Covid 19 WFH, ultra-low interest rates, emergence of zero commission trading platforms like Robin Hood, financing engineering like fractional trading, and discussion forums like Reddit involving largely day traders have brought stock market investing to the masses, but perhaps with undesirable consequences. Sample this,

Throw in social media Fomo (fear of missing out), Reddit’s mantra of Yolo (you only live once), and a bull market driven by Covid stimulus, and the GameStop saga looks inevitable.

And worryingly, all these are largely unregulated and un-coordinated actions of millions of retail investors in supposedly efficient markets. It questions the very premise behind markets as self-correcting.

It was also a humbling moment for mighty hedge funds. They now realise that they could be at the mercy of the unforeseeable outcomes of an emergent collective.

To paraphrase Keynes, markets becoming more liquid and efficient increases the likelihood of participants becoming insolvent!

Matt Levine has this description of the driving force behind such episodes,

The stock of a micro-cap company called Signal Advance Inc... shot up 5,100% after Elon Musk tweeted something about an unrelated app named Signal. The error, as it were, was quickly corrected: Lots of news stories, and a tweet from the “real” Signal, clarified that Musk was not talking about Signal Advance. The stock kept going up. (It’s still trading at roughly 10 times its pre-tweet price, weeks later.) Perhaps the buyers were impenetrably ignorant, but I suggested another possibility: There is a mass of retail buyers who like to all buy the same stock, and Musk’s tweet gave them a Schelling point to coordinate around. They weren’t confused about what Musk meant; they didn’t care that much about what Musk meant. They just like to all have fun together, pumping some stocks. You don’t actually need a Schelling point to coordinate around. You can just go on Reddit and talk about what stock you’re all going to buy...Bitcoin is a financial asset with no cash flows. It has value purely because people think it’s valuable. Bitcoin is worth $34,000 because other people will pay you $34,000 for it, and they’ll pay you $34,000 because other people will pay them $34,000, etc. There is no underlying claim; there is just a widespread acknowledgment that people think it’s valuable... It is an amazing collective accomplishment to create a new thing, from scratch, that is valuable just because we collectively agree that it’s valuable. It is amazing to find a way to create that collective agreement from nowhere. Once you have it, you can actually do useful things with Bitcoin—as a store of value, a currency, whatever—that you couldn’t do before. Bitcoin created real financial value out of, essentially, the human imagination. That’s cool but it’s also a terrifying proof of concept. If pure collective will can create a valuable financial asset, without any reference to cash flows or fundamentals, then all you need is a collective and some will. Just hop on Reddit and create value out of nothing. If it works for Bitcoin, why not … anything? Why not Dogecoin? Why not Signal Advance? Tesla Inc.? GameStop?

Or this by Jason Zweig,

Decades ago, small investors might pay as much as 5% to trade a stock. A stockbroker was a 9-to-5 guy in a paneled office who picked your pocket on every trade. Nowadays, your stockbroker is in your pocket, as apps on your phone let you trade stocks at zero commissions, anytime you want. WallStreetBets is the ultimate stage of this evolution. Thousands of people can amass small trades into giant pools of capital and whip each other into a collective frenzy. In what neuroscientists call “dynamic coupling,” the brain activations of different people doing the same task converge, firing in sync. In such situations, says Princeton University neuroscientist Uri Hasson, “I’m shaping the way you behave and you’re shaping the way I’m behaving. And coordinated behavior across many, many individuals can generate dynamics that are larger than anything they could produce separately.”

Amen!