I had blogged here earlier about Yuen Yuen Ang's latet book, China's Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Growth and Vast Corruption. This podcast is a good summary of the book. And this and this book discussions too.

She classifies corruption using a framework as below. I had blogged here earlier about this framework.

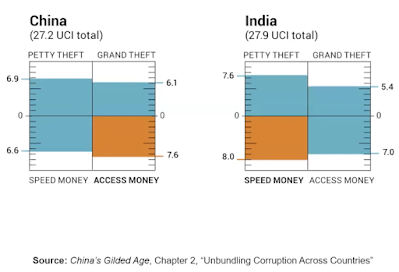

She makes the distinction between growth damaging and promoting forms of corruption. Theft like extortion and embezzlement belongs to the former and access money to the latter. She defines access money as the purchase of influence by the capitalists from those in power. Access money exacerbates inequality. In this model, state-business relationship are not extractive, but transactional.

She uses the framework to assess corruption in different countries.

In countries like India power is diffused across large and fragmented bureaucracies leaving officials with limited power to get things done on their own but with significant power to create obstacles, bribes are primarily paid to overcome the numerous hurdles created by the bureaucracy. In contrast, in China since power is concentrated in local leaders who have the power to definitively confer favours, bribes are made to win those favours.

Yuen's central point is that Chinese growth has been powered by access money, whereas the growth hampering forms of theft have declined.

Yuen describes China as a "capitalist dictatorships disguised as communist", with the dominant belief of each according to his needs, to each according to his ability and connections. Consistent with this, she also describes China as a "corrupt meritocracy".

But this, she argues, in turn, creates its set of distortions and risks. Xi Jinping thinks corruption is an existential problem, in so far as it can destroy both the Party and economic growth. He is worried about grand transactional corruption enmeshed with patron-client relationships among political elites and senior party leaders.

Yuen points to two fault lines on how corruption can impact the Chinese political system.

Chinese corruption can intensify factional rivalries. Fiefdoms amass astronomical rents and become ambitious and defiant of the top leadership. They also become powerful enough to take on central leadership when their interests are hurt. Such internal implosions are not non-trivial.

Another rupture point is when the structural risks linked to crony capitalism implode. For example the debt pile has the potential to deeply destabilise the system. This also explains Xi's focus on debt reduction and deflating the property bubble.

Another risk is that of corruption moving away from the traditional real estate, infrastructure, and manufacturing sectors. Take the example of Government Guiding Funds (GGF). As of end-2017, there were 1500 of them managing $1.4 trillion in funds, with the mandate of investing in technology and innovation sectors. It is a form of industrial policy that uses public funds as seed money to invest in these sectors. The GGFs are effectively funds of funds, allocating the funds to traditional venture capital and other investors to in turn invest in innovation and technologies. This could become the new source of corruption. It is not clear how these funds are disbursed, to whom, and why. Holding fund managers accountable for their investment decisions are in any case difficult.

Illegal embezzlement and bribery, and vote-buying are the traditional forms of corruption in developing countries. Undue influence and influence buying through lobbying to distort political outcomes. Such purchase of influence is often legitimate and its activities are perfectly legal. One example is revolving door. Even businesses (like say the tech firms) may not even view influence peddling actions to change the rules of the game as corruption.

Take the case of lobbying. It becomes corruption only when it crosses the line to advance narrow interests at the expense of society. But how we do know this is happening, especially when cause and effect are difficult or even impossible to disentangle? When does lobbying cross the line to become corruption?

How do we know that there was no corruption when Lloyd Blankfein and Co had such privileged access to Hank Paulson when he was designing a program to bail them all out? How do we know that there was no corruption when Obama met the Chief Executives of Honeywell and GE 30 and 22 times respectively in the 2009-15 period and those visits were accompanied by favourable regulatory or other benefits and abnormal share price increases for the respective companies?

Bribery is easy to identify as corruption. But less easily identifiable forms of corruption, which are likely more pervasive in developed countries, may actually be much bigger and more corrosive.

No comments:

Post a Comment