It’s not a hyperbole to argue that managing economic relations with China is the biggest problem facing the world economy. Its dominance of manufacturing sectors is so stifling that allowing any further deepening is undesirable while reducing the reliance is very hard.

For a long time, China’s manufacturing prowess was the subject of global praise - its exports of textiles, footwear, consumer durables etc., expanded consumption and lowered inflation globally, and its cheap solar and other green technologies expedited the green transition. But as Econ 101 reminds us, there are no free lunches. In the absence of concomitant import demand from China, these gains for the world economy were accompanied by a creeping de-industrialisation across China’s trade partners. As I blogged here, China became the country with a comparative advantage in everything leaving nothing to others. China's industrial policy is the mother of all beggar-thy-neighbour policies.

Its industrial policies that rely on massive subsidisation of critical industries have the effect of concentrating supply chains and control over critical industries, making local firms in developed and developing countries uncompetitive and forcing them out and generally de-industrialising economies. All this coupled with the country’s propensity to weaponise its dominance of these industries make it a severe national security hazard for developed and developing countries alike.

The narrative on Chinese manufacturing dominance has recently been dominated by its impact on the destruction of industrial bases in developed countries. There’s now evidence that its adverse impact on the manufacturing base is even greater for developing countries.

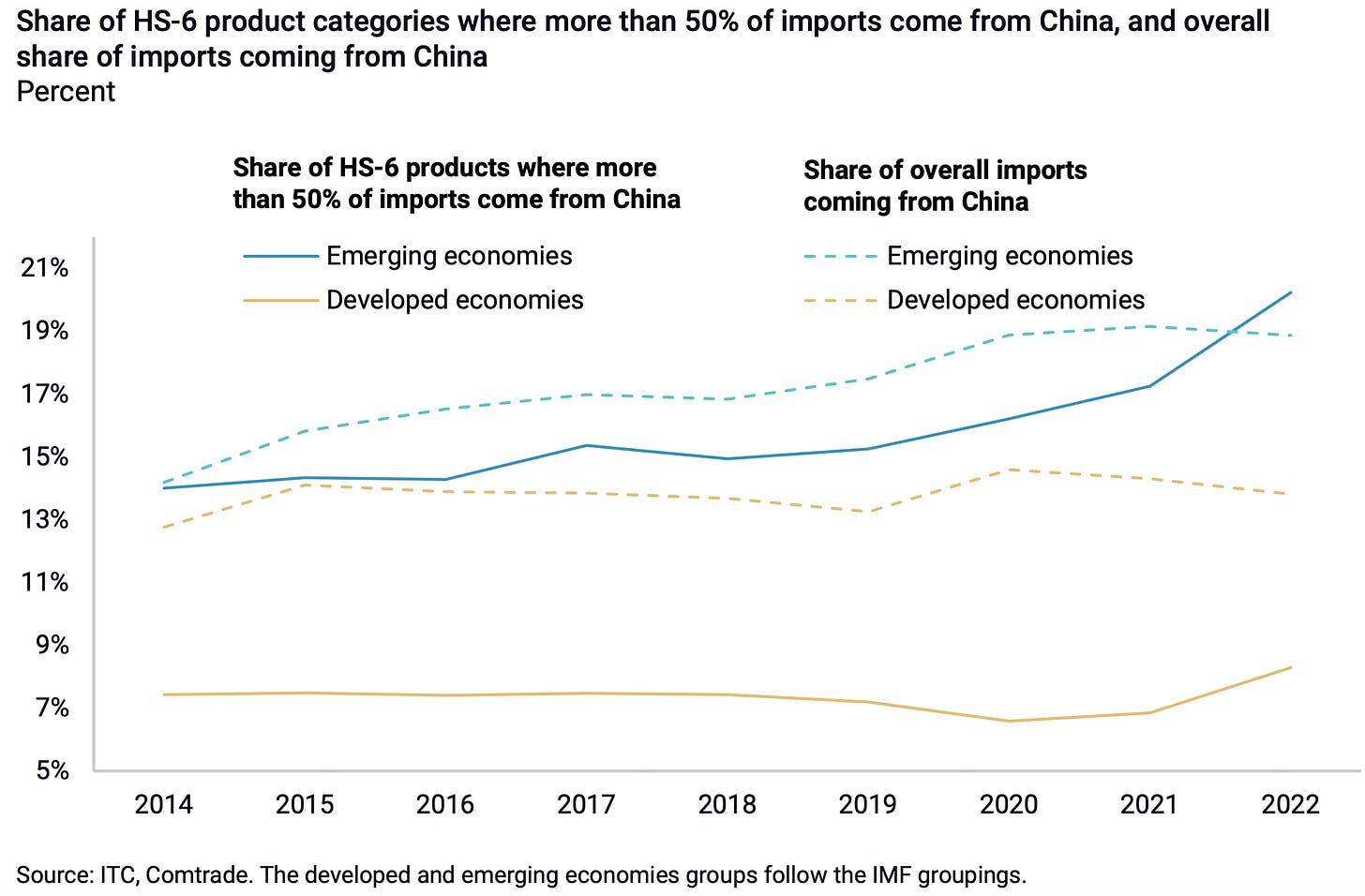

A recent report by the Rhodium Group discussed how China’s manufacturing overcapacity threatens to crowd out developing nations from manufacturing. It finds that emerging economies were reliant on China for more than half their imports in 20% of all HS-6 product categories in 2022, up from 15% in 2019.

In contrast to the increasing dependence of developing countries on Chinese imports, the developed economies’ reliance on China is lower and has risen less sharply. It rose by just one percentage point in the same period to 8%.

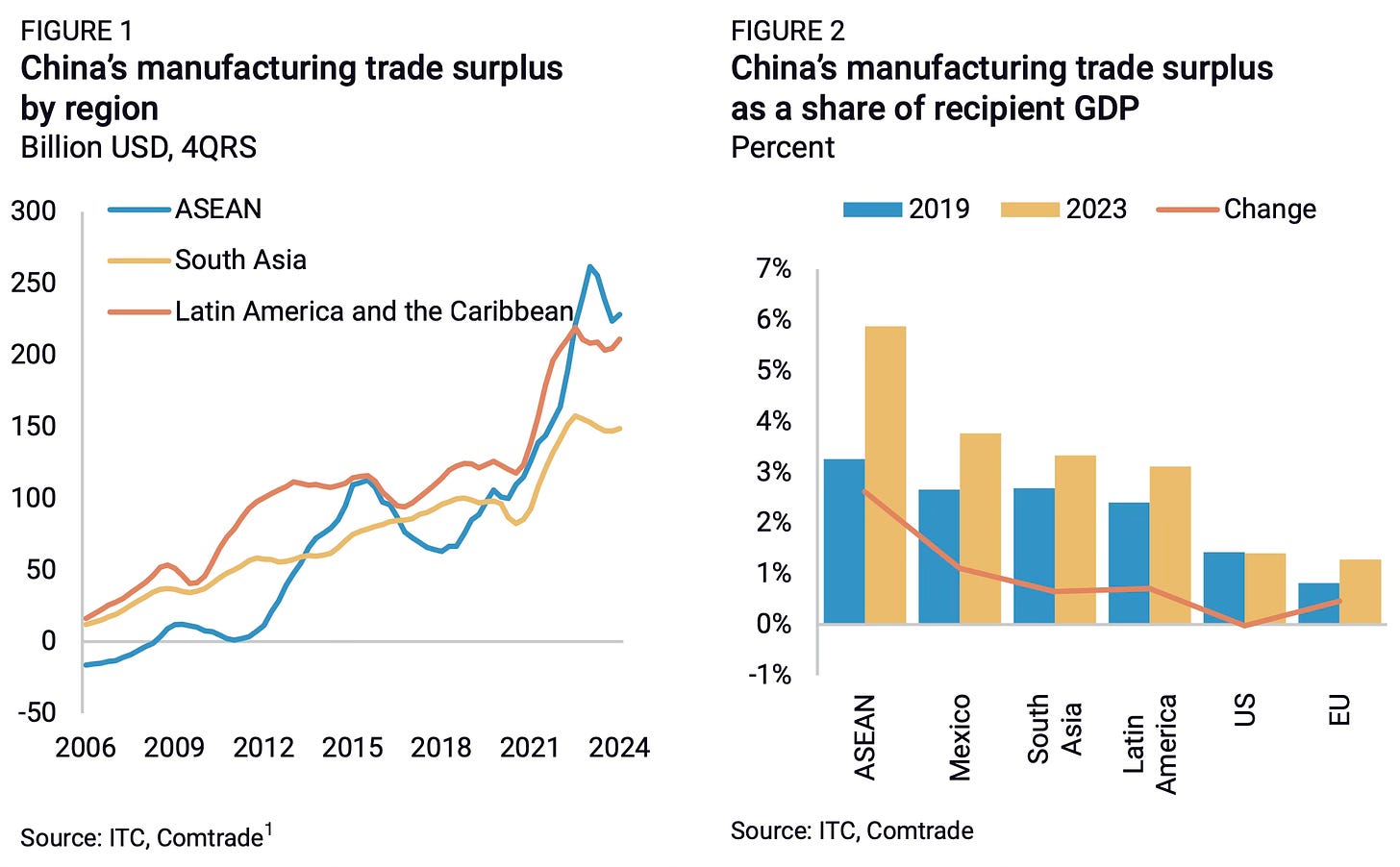

China’s manufacturing trade surplus with its favoured trade partners among developing countries is rising sharply, whereas those with the US and and EU are declining or stagnant.

The report nicely captures the problems with China’s manufacturing dominance.

China’s share of global exports has variously been surpassed by at least one other major exporter (such as the US, Japan, or the EU) over the last few decades, but no other country has had the same level of global dominance across product categories since the early 1970s. Moreover, achieving that level of dominance is more significant now than in prior decades, when trade represented a much lower share of global goods production and consumption. For comparison, the global trade-to-GDP ratio in 1970 was around 25%. By 2022, that had risen to 63%. China’s dominance over so many product categories creates, first and foremost, a risk of economic coercion, where the government restrains access to crucial inputs for political leverage. Examples already exist, from rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 to more recent export controls on solar panels and other technologies and reported denied access to solar equipment in India…

But compared to other leading trading nations throughout history, the Chinese state is heavily interventionist, managing competition between its domestic firms and their external trade relations. State-owned enterprises accounted for half of China’s top 100 listed firm market capitalization in 2023 and 70% of listed companies declared that they hosted Communist Party cells within the firm as of 2022. This means that the Chinese government can encourage companies to partner together, merge and consolidate, coordinate to gain market shares, raise prices, restrict access to products where they already have substantial market power, or favor domestic firms in their suppliers and client networks. As a result, China’s dominant position across so many product categories considerably limits the space for new entrants to emerge as new manufacturing powers.

Such a strong dominance in export markets also means that developing countries are vulnerable to changes within the domestic environment in China. Weakening domestic demand, combined with export-facilitating policies in products where China is the world’s dominant manufacturer, can cause prices to collapse globally and drive other national producers out of business. Consider the steel industry, where China accounts for more than half of global production. China’s property sector woes since 2021 caused vast overcapacity and led to a collapse in global prices, which now puts significant pressure on producers in India, Vietnam, Brazil, and other countries. China’s steel product exports are surging again—by 27% so far in 2024—after 35% growth last year…

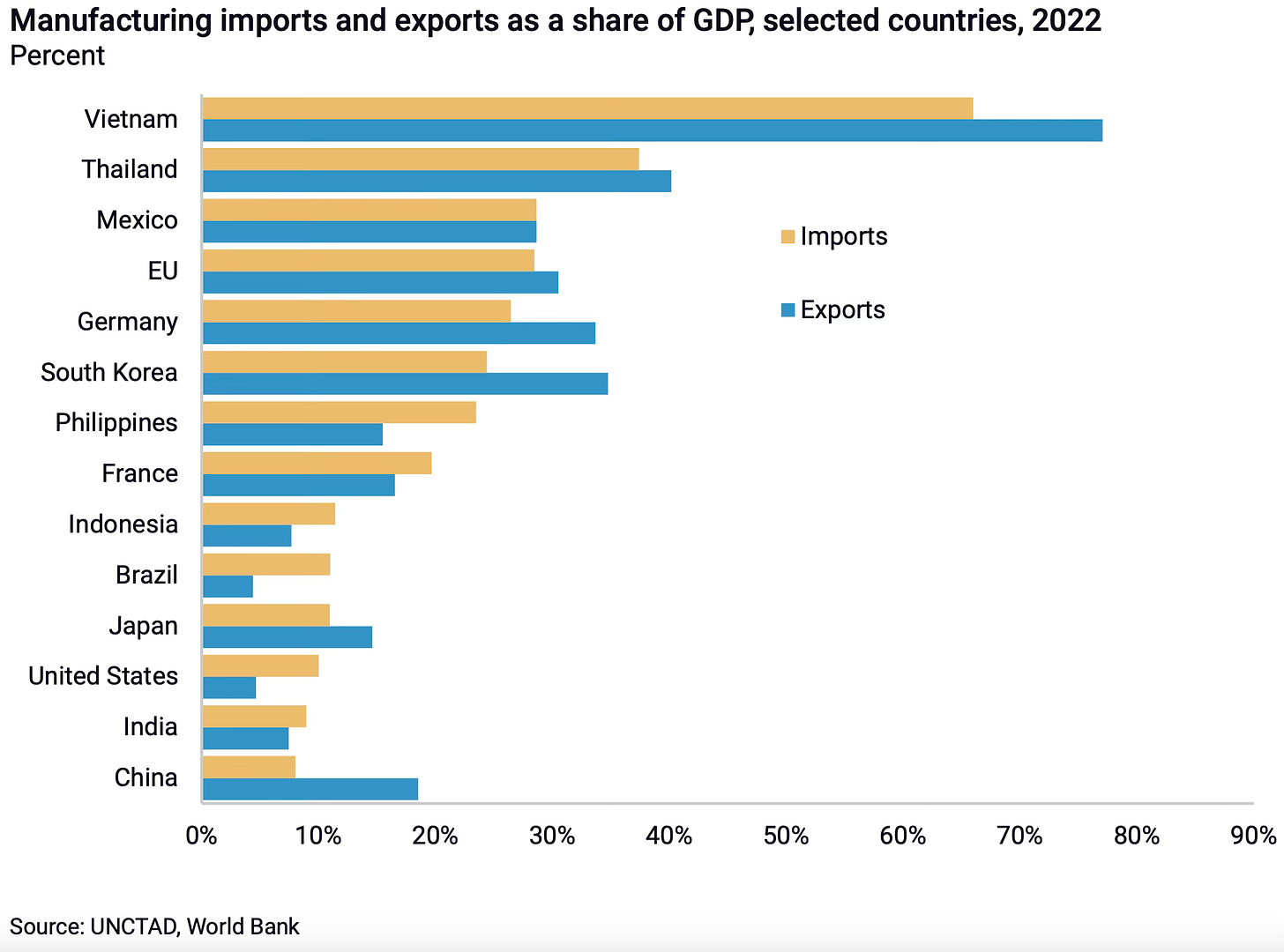

Despite the country’s economic heft and manufacturing prowess, its dependence on the rest of the world (as reflected in its imports) has been remarkably minimal. Its economic growth trajectory has deviated from the standard flying geese model of moving up the value chain and vacating the lower-skill sectors for other emerging economies.

Over the past two decades, China’s move up the global value chain was expected to create massive demand for low value-added manufactured goods. This underpinned expectations of industrial development in emerging economies. That assumption is now undermined by China’s weak domestic demand and the growing gap between its manufacturing exports and imports. This gap is by far the largest in the world, and almost an order of magnitude larger than that of the worst years of trade imbalances in Germany, Japan, and South Korea. More than export competitiveness, weak Chinese imports explain this imbalance. Given the size of its economy, China is not exceptional in its large volume of manufacturing exports, but China has seen lower import volumes of manufactured goods than all other large economies in the world. Much of that imbalance can be explained by the small contribution of China’s household consumption to economic growth, which is the result of Beijing’s systematic policy support for producers and weak fiscal support for consumers. China’s domestic demand for imported manufacturing goods has been weak for years but was somewhat obscured by China’s reliance on imports related to the processing trade for re-export, and commodities imports. Both of the latter categories are now under pressure, particularly because of the slowdown in construction activity.

Since 2019, China’s manufacturing imports from emerging economies, already weak relative to the size of its economy, have plateaued in absolute terms for countries like Vietnam, or outright declined in the case of Malaysia and Thailand. Put differently, if China had increased its manufacturing imports as much as its exports since 2019, it would have created an additional $363 billion in import demand in 2022, or the equivalent of 11% of total manufacturing exports from developing countries. If it simply imported manufactured goods as much as it exported them in 2022, the additional demand would be equivalent to 54% of developing countries’ total manufacturing exports… While China still needs to import high-tech products from rich industrialized economies, it imports very few low-tech goods, where developing countries would have a comparative advantage. This is largely a result of deliberate policy interventions, which have intensified in recent years. While the central government has long emphasized developing high-tech industries, local governments sought to sustain low-end manufacturing companies through subsidies and other types of state support, because they are a vital source of local employment.

… since 2021, China’s high-level economic strategy has shifted emphasis toward retaining low-tech manufacturing jobs and production… As Xi Jinping remarked in 2023, China must “insist on promoting the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries and cannot regard them as ‘low-end industries’ to simply abandon.” Many provincial five-year plans followed suit, outlining quantified targets for the share of manufacturing in the local economy. As a result, deliberate policy interventions to retain low-end manufacturing have multiplied, with visible consequences on manufacturing jobs and production. The result is that China provides fewer opportunities as an export market for emerging countries while competing head-on with them in the low-tech and mid-tech space.

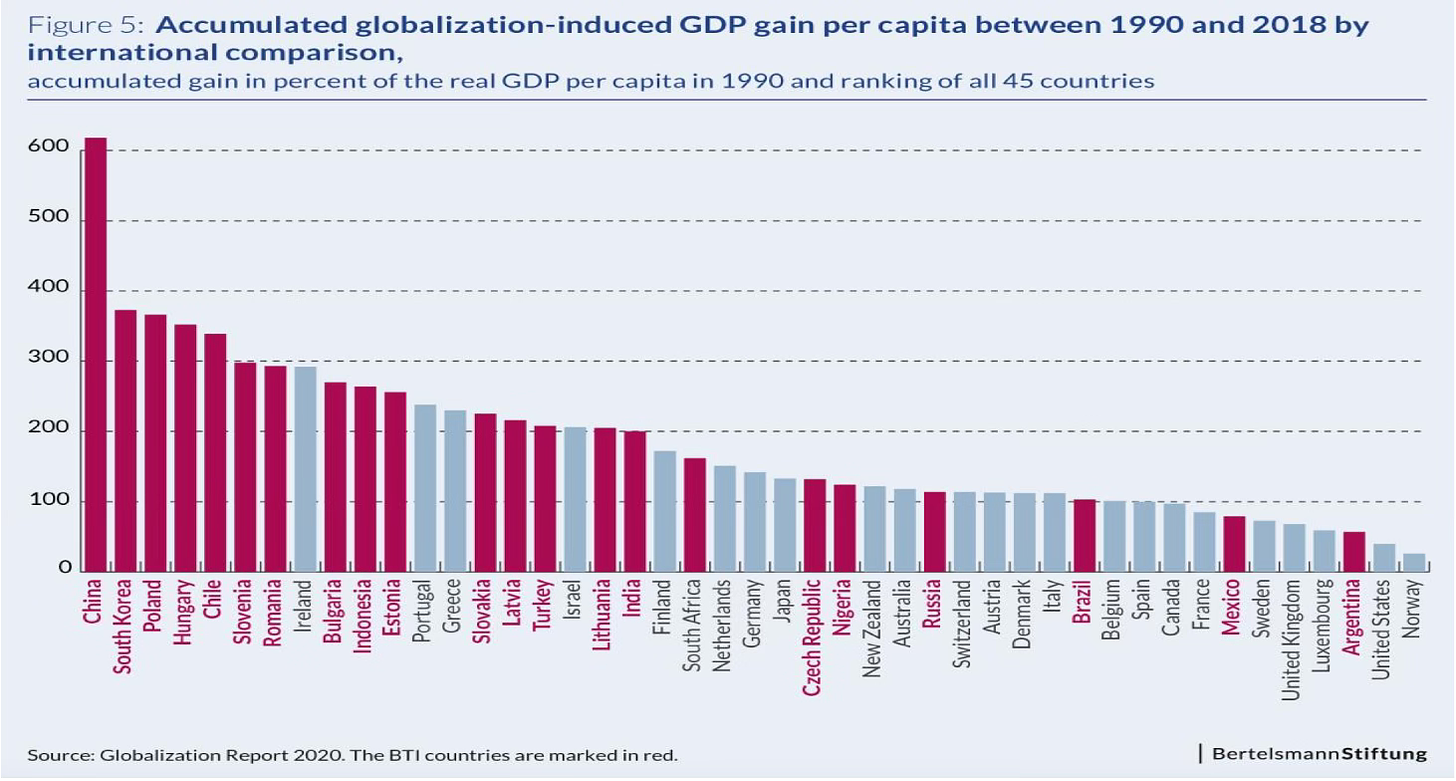

This graphic from a Bertelsmann Stiftung study shows that there has been only one mega beneficiary from globalisation and trade liberalisation, China! Others picked up the crumbs.

The result of large hidden subsidies is a competitive advantage that no country can match.

US-made crystalline silicon panels generate energy at an average cost of 29.5 cents per watt, while First Solar’s panels hover above 30 cents per watt and were less efficient, according to BloombergNEF. A panel sourced in south-east Asia, meanwhile, can cost under 16 cents per watt, and in China, it is 10 cents per watt.

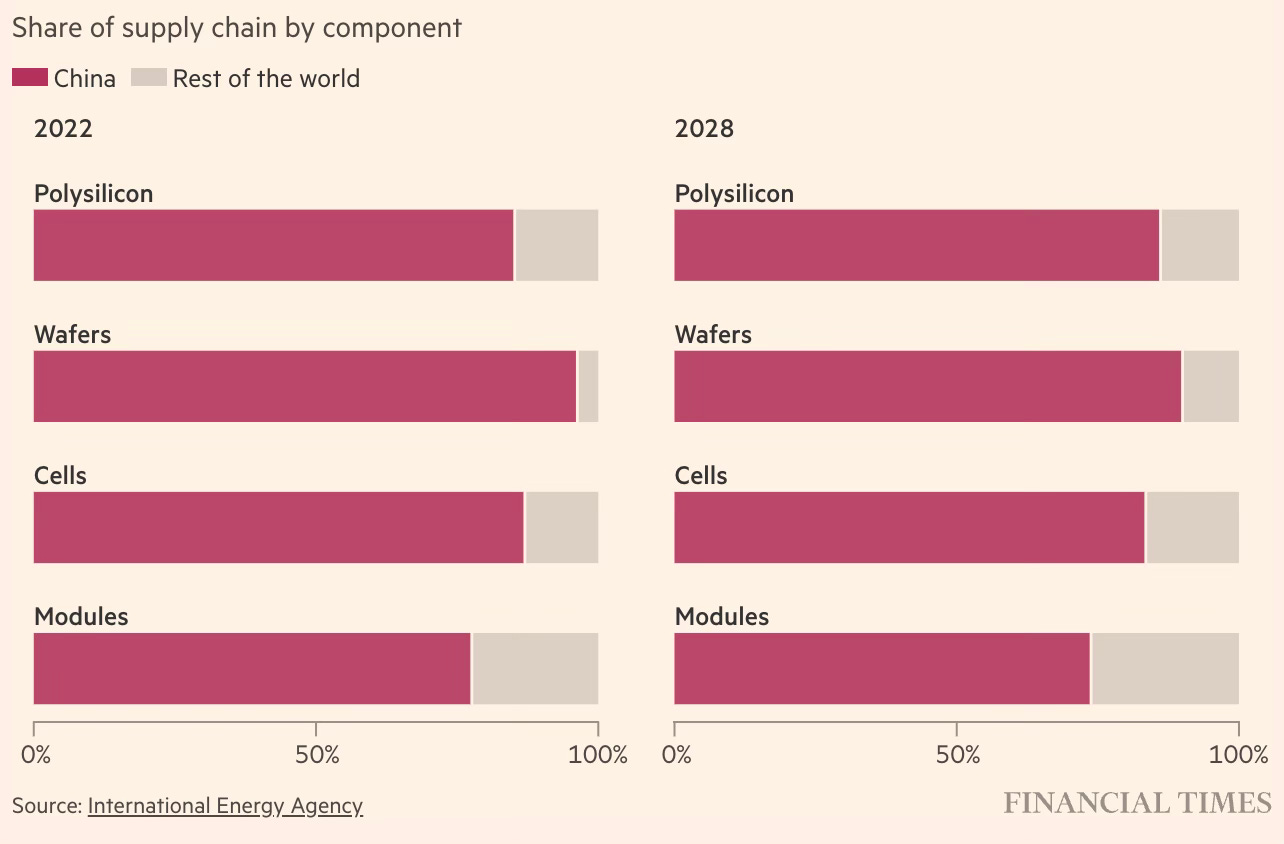

The result of this is a stranglehold on the solar industry supply chain that is nearly complete.

China's global dominance of the solar power generation market co-exists with companies making those wafers, cells, and panels, and their equipment losing money! Sample this from a story in NYT.

Nearly every solar panel on the planet is made by a Chinese company. Even the equipment to manufacture solar panels is made almost entirely in China... But China’s solar panel domestic industry is in upheaval. Wholesale prices plummeted by almost half last year and have fallen another 25 percent this year. Chinese manufacturers are competing for customers by cutting prices far below their costs, and still keep building more factories. The price slashing has taken a severe toll on China’s solar companies. Stock prices of its five biggest makers of panels and other equipment have halved in the past 12 months. Since late June, at least seven large Chinese manufacturers have warned that they will announce heavy losses for the first half of this year... Compounding the problems facing China’s solar energy companies is the rapid disappearance of local subsidies. Local governments are running out of money as a housing crisis makes it hard for them to sell long-term leases on state land to real estate developers — previously their biggest source of cash…

The West is raising barriers to China’s solar panels. Europe has begun barring their use in government procurement projects unless Chinese companies disclose their subsidies, which they refuse to do. Partly because of worries about Chinese subsidies, President Biden last month allowed steep tariffs that had expired to go back into force on solar products imported from Southeast Asia that use lots of Chinese components…

Solar manufacturers across China have been laying off thousands of workers to cut costs — and those workers may be the lucky ones because they qualify for months of severance pay. Other big solar companies have resorted to tactics like giving yearlong unpaid vacations or 30 percent pay cuts for employees who keep their jobs.

The article highlights the example of one solar panel manufacturer

The rise and fall of Hunan Sunzone Optoelectronics in Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province in south-central China, is a case study of how China’s policies work. Started in 2008, the solar panel manufacturer benefited early on from practically every possible subsidy. It got 22 acres of prime land in the heart of the city almost for free. One of China’s biggest state-owned banks arranged a loan at a low interest rate. The Hunan provincial government then agreed to pay most of the interest. Despite the financial help, Sunzone’s factory now sits empty... Sunzone epitomizes how lavish lending from state-owned banks and generous local subsidies have produced manufacturing overcapacity. Solar companies cut costs and prices sharply to maintain market share. That led to a few low-cost survivors while many other competitors were driven out of business in China and around the world. China’s banks, acting at Beijing’s direction, have lent so much money to the sector for factory construction that the country’s solar factory capacity is roughly double the entire world’s demand. Sunzone’s 360-employee factory was big when it was built. Within a few years, rivals elsewhere in China were building much larger factories...

The storyline in solar is being repeated in the automotive sector.

Annual car sales in China are around 25 million, more than any other country but barely half the country’s ability to make vehicles. So automakers in China are now following the solar industry’s lead in cutting prices sharply and ramping up exports. China’s approach can lead to big financial losses for local governments, state investment funds and state-supported banks, all of which bankroll companies in favored industries.

Another NYT article describes how Chinese EV makers and their imports are making rapid ingress into Thailand and shaping the country’s EV industry in the manner that China wants. The Chinese EV makers see Thailand as a beachhead and are therefore focused on first capturing the local market and then establishing themselves for exports. And they are trying to do it rapidly enough before the global squeeze on Chinese manufacturers led by the US and EU starts to bind in countries like Thailand too.

Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers like Aion are stampeding into overseas markets. Thailand is one of the first countries to experience the sudden influx of China’s automobile brands, and is confronting how their ambition and competitiveness are reshaping its car industry. The arrival of China E.V. Inc. is evident everywhere in Thailand. Billboards are blanketed with advertisements for Chinese cars. Land prices are soaring because so many Chinese firms are building car factories. The fast changes in the Thai auto market also show how Chinese companies are leaping ahead of their global rivals in Japan, which has shunned E.V.s, and the United States, where Tesla dominates the sector. Last year, sales of popular Japanese brands such as Nissan, Mazda and Mitsubishi plummeted as consumers bought new electric cars from Chinese manufacturers instead. Dealers that had worked with Japanese and American automakers for decades were now turning over showrooms to make way for Chinese vehicles. Amid an increasingly crowded field, Chinese brands are slashing prices on electric vehicles.

The overseas push is the next phase in Beijing’s long-term strategy to focus on new energy vehicles and upend the balance of power in the automobile industry. After years of government support for the sector, Chinese manufacturers are adept at mass-producing electric vehicles. They have established dependable supply chains, while working out the kinks to reduce prices. That international push has been met with tariffs in two major auto markets to prevent a glut of Chinese vehicles from crushing homegrown competitors. Last month, the European Union said it would impose tariffs of up to 38 percent on electric vehicles imported from China into the bloc. A month earlier, the United States quadrupled tariffs on E.V.s built in China. Thailand is small by comparison, but it is the biggest market in Southeast Asia. Known as the “Detroit of Asia,” it serves as a regional manufacturing hub. Its proximity and strong trade ties to China also allow Chinese cars to be imported quickly and inexpensively… In a market once considered a Japanese stronghold, a changing of the guard is already happening. Japanese automobile brands accounted for 86 percent of new car sales in 2022. That figure dropped to 75 percent last year, with China’s BYD, Great Wall Motor and SAIC Motor grabbing significant market share.

Realising the rapidly expanding squeeze on Chinese imports in developed countries, Chinese manufacturers across critical industries are adopting a two-pronged strategy to shed production from their massive excess capacity.

On the one hand, they are expanding aggressively with low-priced imports to developing markets like Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Africa. Countries like Poland, Hungary, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Thailand etc., are at the forefront of this rush to capture large and strategically important developing country markets. The local manufacturers stand little or no chance when faced with the heavily subsidised low-priced dumping of Chinese EVs. This capture of local markets is being complemented with efforts to form joint ventures and establish Chinese-controlled manufacturing facilities in these countries to use them as a base for exports to advanced countries.

A combination of these two would make it more difficult for US and European efforts to keep out Chinese manufacturers, besides also deepening the country’s hold on the global supply chains and the industry itself. And the Chinese manufacturers are pursuing this strategy at great speed to capture as much market leverage as possible before the US and EU-led squeeze tightens further.

“The window of opportunity for Chinese new energy vehicles going overseas will be relatively short,” said Ma Haiyang, general manager at Aion for Southeast Asia. “This is why we wanted to hurry up.”... Six Chinese electric vehicle companies are already selling cars in Thailand, and three more entrants are coming this year. BYD, Aion, Great Wall, Hozon Auto’s Neta and Chery are among those that have opened or are building factories in Thailand… Aion, in its first year in Thailand, has opened 41 showrooms and started production at a new factory this month. It has announced plans to open a plant in Indonesia and start selling its cars in nine countries across Southeast Asia.

The Chinese have been adept at dangling carrots and striking alliances with strategically important partners.

Japan’s dominance over Thailand’s automotive industry dates to the 1960s when Nissan Motor and its local partner, Siam Motors, opened the country’s first car factory. Japan’s support helped establish the Phornprapha family, which owns the privately held Siam Motors, as the first family of Thailand’s car industry. But even within the Phornprapha family, alliances are shifting. Pratarnwong Phornprapha and Pratarnporn Phornprapha, the grandchildren of Siam Motors’ founder, control Rever Automotive, which is the exclusive distributor for BYD cars in Thailand. BYD, China’s leading E.V. company, competes directly with Siam Motors’ longtime partner, Nissan. BYD sold more cars in Thailand than Nissan did last year, even though the Chinese automaker had only three models available… This month, BYD said it had acquired a 20 percent stake in Rever for an undisclosed sum. In less than two years, Rever has opened 110 showrooms across the country, with the goal of another 50 by the end of 2024. Pratarnwong Phornprapha, the Rever chief executive, said there had been no tension within the family, because Rever was focused on electric vehicles and Siam Motors made traditional cars.

An example of this creeping capture of a country’s manufacturing base is Indonesia’s nickel industry, which has come to be dominated by Chinese companies.

About 80 to 82 per cent of its battery-grade nickel output is expected to come from majority Chinese-owned producers this year, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. This stems from Jakarta banning nickel ore exports in 2020 to force processors and battery makers to invest in the country. Chinese companies came forward quickly with billions of dollars. The investments have transformed the economy and made the nation a critical player in the global EV transition. Indonesia accounts for 57 per cent of global refined nickel production, and its share is forecast to rise to 69 per cent by the end of the decade, according to BMI. Only a handful of foreign companies that are not Chinese operate in the Indonesian nickel industry.

The Indonesian government is now trying to reduce Chinese influence and is finding it a big challenge.

Indonesia is trying to reduce Chinese investment in new nickel mining and processing projects to help its industry qualify for tax breaks in the US… Generous tax breaks are available from 2025 under President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, but they will not apply to EVs containing batteries and critical minerals such as nickel sourced from “foreign entities of concern”, including some companies with more than 25 per cent Chinese ownership. That would hurt Indonesia’s industry, which has become the world’s biggest supplier of nickel on the back of a huge influx of Chinese capital over the past four years into mining and smelting projects. Indonesia’s government and industry are now working to structure new nickel investment deals with Chinese companies as minority shareholders… Last year, Indonesian government officials asked some Chinese companies if they would be open to taking a minority stake of about 15 per cent in nickel projects, according to an executive at a nickel producer.

Another example is Kazakhstan that has critical minerals like Nickel and where the Chinese are investing heavily to strengthen their control over the supply chain.

In this context, the Indian authorities should be watchful of the Chinese strategy in areas like solar panels and EVs. Like in Thailand, the Chinese have been quick to strike alliances with India’s big business groups. There are emerging partnerships between Chinese companies and the Ambani and Adani Groups, and other influential Indian corporate groups in the green technologies space. Indian groups are vulnerable to being allured into financially beneficial deals as virtual sleeping partners. It’s important that they be nudged or mandated to wrest significant technology transfers and local value addition in these partnerships.

In this context, India should be closely scrutinising the entry of Shein on the platform of Reliance Retail and JioMart. The cheap imports of Shein can become one more nail in the coffin of an already flagging local textile manufacturing base. It’s essential to have significant domestic content requirements that prevent wholesale import or cosmetic value addition in India. Shein can become the backdoor for the Chinese capture of what’s left of India’s textile and garment industry.

I’m also not sure about how far developing countries can go with attracting Chinese investments as FDI, for some reasons. One, China has preferred debt to FDI as the dominant means of exporting capital. This is clearly borne out by the BRI, which focused on debt-financed infrastructure creation and largely stayed away from manufacturing investments. Similarly, its several natural resource deals in Africa and elsewhere have focused on extraction and exports, and avoided mineral processing investments in the host countries.

Two, as the US and other advanced countries tighten their squeeze on China, it’ll no longer be easy for Chinese companies to access Western markets through the backdoor from other markets. This makes such joint ventures largely blunt as an export-promotion industrialisation strategy. Three, the Chinese companies don’t have a problem of large equity capital waiting to be channelled into investments in other countries. The country’s problem is not excess capital, but excess capacity that can be addressed only through exports. Given the well-documented profitability problems being faced by them, I’m not even sure they have the sort of risk capital to invest and expand in other markets on purely commercial considerations.

Finally, given that all major economic strategies are dictated by the Party based on national interests, I don’t see how investing in building manufacturing capabilities in countries like India can further Chinese interests. Even if such capital comes to India as FDI, it’s most likely tied with enough levers to limit technology flows and with limited value addition, besides posing unseen strategic risks.

No comments:

Post a Comment