The World Development Report (WDR) 2024 is out and it’s about avoiding the middle-income trap and presents a strategy for developing countries to reach high income status. The report has several useful insights and is a good documentation of the challenges associated with the middle-income trap.

This post comments on the report and questions a few important assumptions and conclusions in the report.

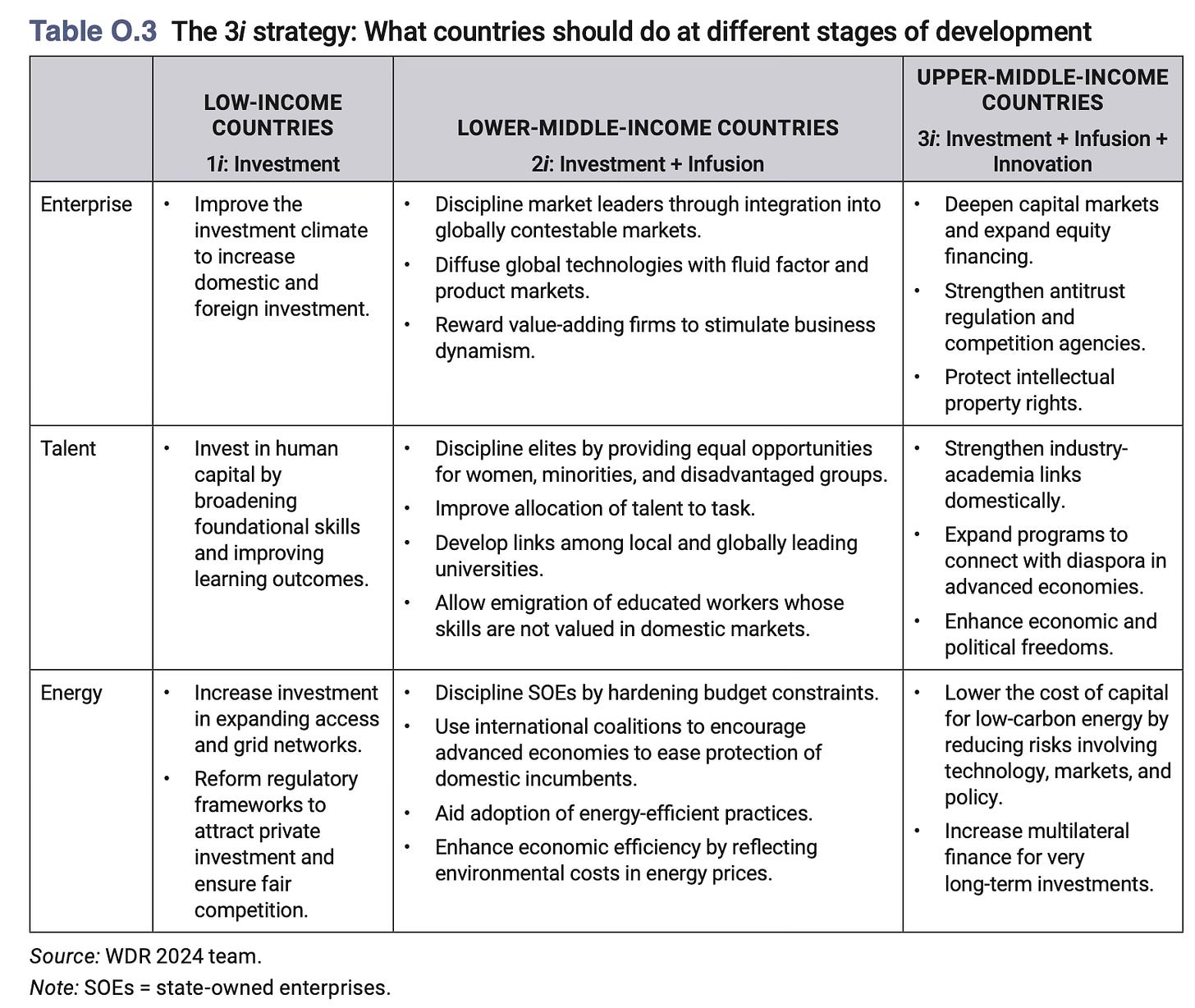

The report describes a three-stage path of transition to high-income status - investment, infusion, and innovation. Lower middle-income countries must transition from their predominantly investment-driven strategies to one where they “must also adopt modern technologies and successful business practices from abroad and infuse them across their economies”. This infusion is through the technology transfers embodied in the transfers of physical and financial capital. The upper-middle-income countries, in turn, should supplement infusion by adopting innovation and engaging at the global frontiers of technology.

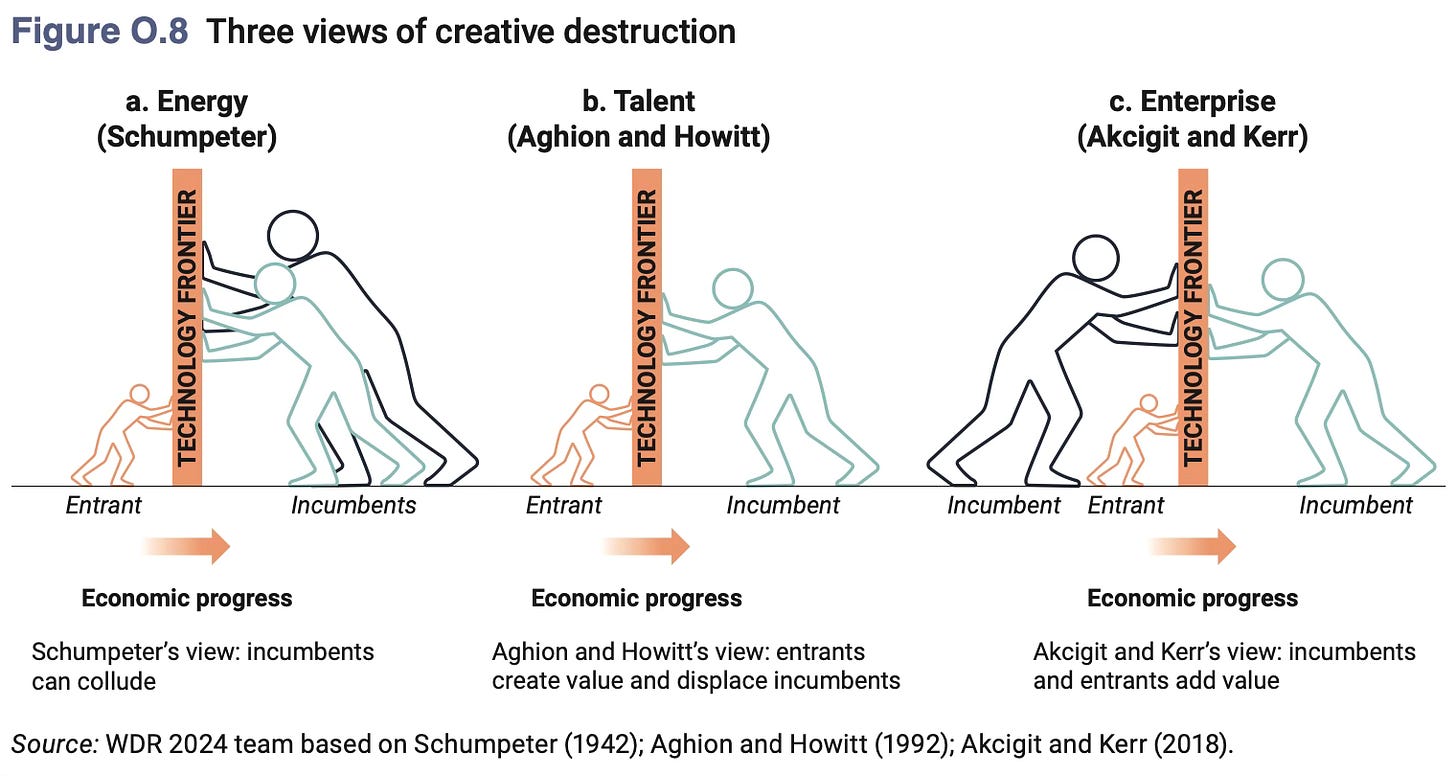

It uses the above framework to describe three processes essential for the Schupeterian creative destruction to play out - creation (where incumbents and entrants expand markets and technology frontiers), preservation (incumbents and elites tend to prefer the status quo and push back at change), and destruction (elimination of misallocated resources to free up the conditions that aid and resources required for creation). Middle-income countries currently face strong headwinds on all three processes.

The report says that achieving a balance between the three processes requires a complement of policies that seek to discipline incumbent vested interests through competition regimes that encourage new entrants, reward merit by becoming better at accumulating and allocating talent across individuals and firms, and capitalise on crises by using the opportunities presented by the climate change to pursue greater energy efficiency and emissions intensity. The first weakens forces of preservation, the second strengthens forces of creation, and the third rides opportunistically to aid destruction.

The table below captures the development strategy that the Report outlines.

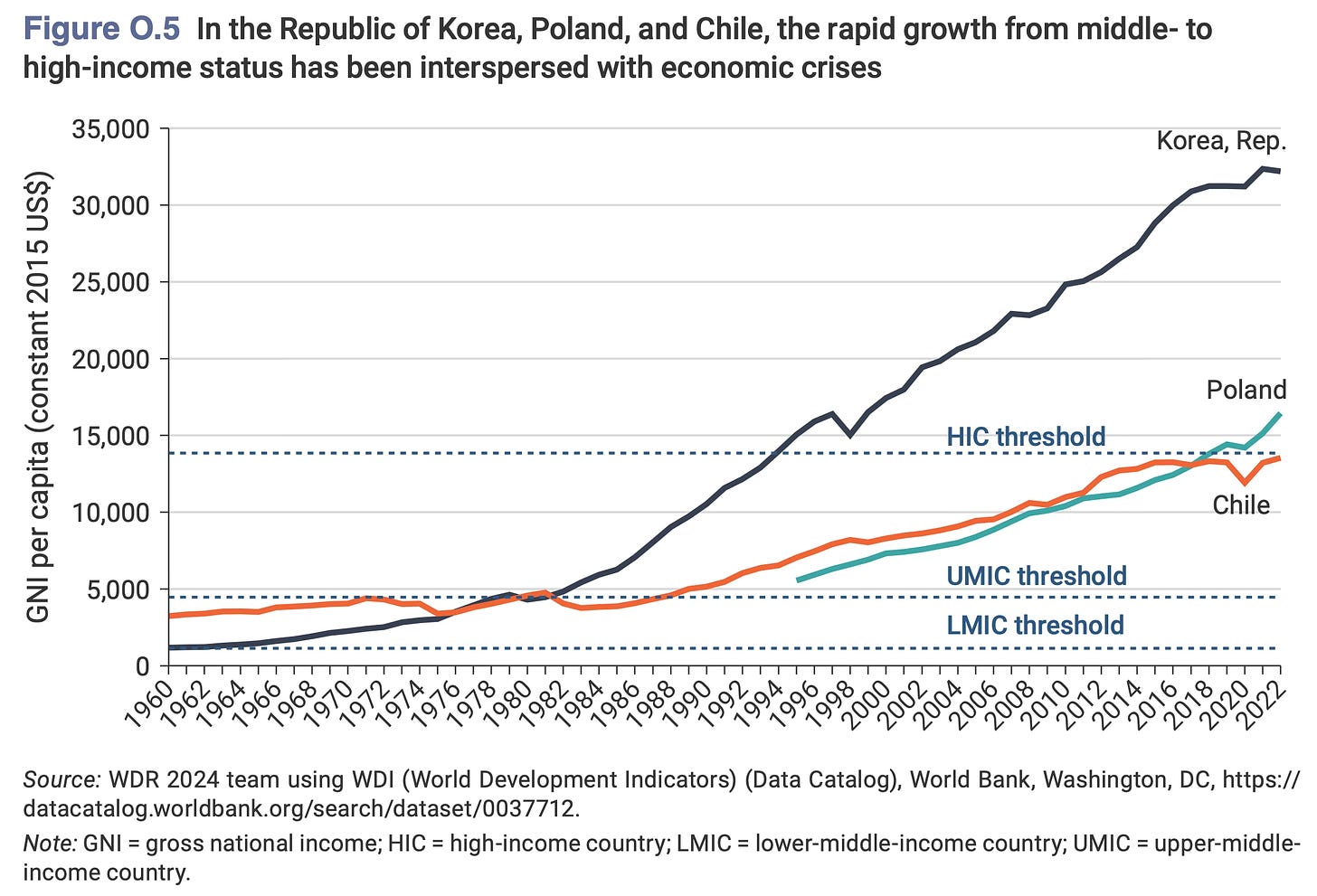

The report uses the case studies of three countries in particular to validate its case.

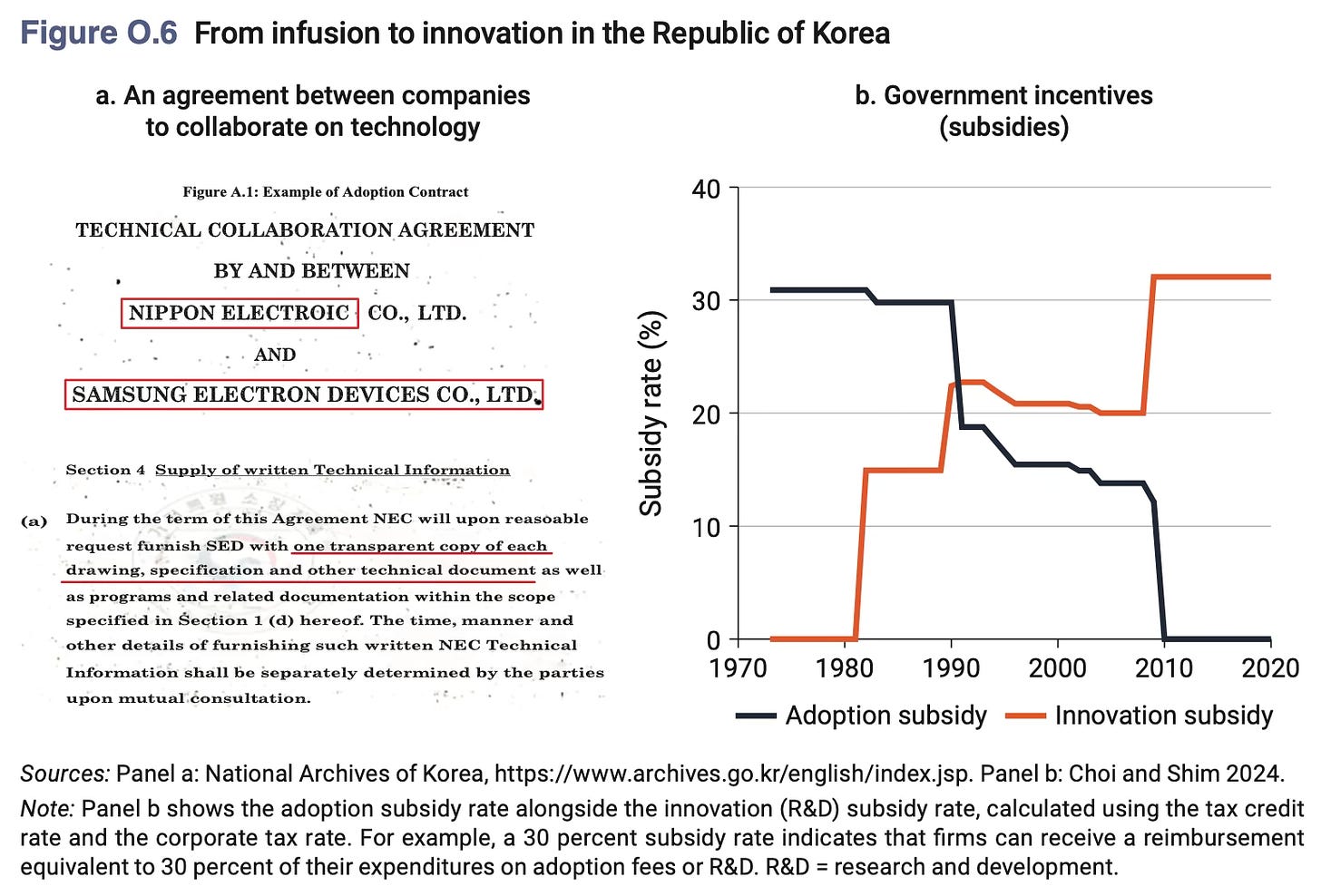

To the extent of the three case studies, the WDR 2024 is a ringing endorsement for industrial policy, albeit carefully calibrated and done in a very sophisticated and iterative manner. Sample this case study of South Korea

In the 1960s, a combination of measures to increase public investment and encourage private investment kick-started growth. In the 1970s and 1980s, Korea’s growth was powered by a potent mix of high investment rates and infusion, aided by an industrial policy that encouraged firms to adopt foreign technologies. Firms received tax credits for royalty payments, and family-owned conglomerates, or chaebols, took the lead in copying technologies from abroad—primarily Japan. As Korean conglomerates caught up with foreign firms and encountered resistance from their erstwhile benefactors, industrial policy shifted toward a 3i strategy supporting innovation. Then, as Korean firms became more sophisticated in what they produced, they needed workers with specialized engineering and management skills. The Ministry of Education, through public universities and the regulation of private institutions, did its part, setting targets, increasing budgets, and monitoring the development of these skills.

Or Poland

In the early 1990s, Poland underwent a transition from a planned economy to a market economy. It has since boosted its income per capita from 20 percent of the average for the European Union to 50 percent. What is Poland’s winning strategy? It began by disciplining the large state-owned enterprises (SOEs). It hardened their budget constraints by cutting subsidies, tightening bank loans, and liberalizing import competition—including at the iconic Stocznia Gdańsk shipyard, where the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement began. This discipline paved the way for comprehensive reform. In Polish SOEs, managers shifted their focus from production targets to profitability and market share, and they upgraded firms’ capabilities to prepare for privatization. Poland then built on this foundation to attract investment, focus on infusion next, and turn to innovation last. It followed this sequence largely by raising productivity with technologies infused from Western Europe—a process accelerated in the 2000s by its entry into the EU common market, which spurred foreign direct investment. Poland also increased tertiary education rates from 15 percent in 2000 to 42 percent in 2012. Educated Poles put their skills to work across the European Union, opening another channel to infusing global knowledge into the Polish economy.

All this is good theory and offers several useful insights. But the framework that the WDR 2024 hangs on struggles when examined with respect to empirical evidence. This post will use the example of India to highlight the point.

First some interesting insights. It does a good work of listing the policy requirements for middle-income transitions - exposure to global competition, connect local firms with market leaders, reduce factor and product market regulation, avoid coddling small firms or vilifying large firms, let go of unproductive firms, strengthen competition agencies, deepen capital markets etc.

The report has a Box item that describes incumbents in a comprehensive manner - firms, technologies, countries, elites, and men. This is an important insight, often forgotten in the analysis surrounding development and economic growth. These incumbents exert significant force of preservation that prevents everyone else from accessing opportunities and contributing to economic growth.

Preservation insulates members of social elites from the forces of destruction that, in a more open society with meritocratic institutions, might dissipate their advantages in wealth and privilege. The same forces ensure that, beyond elites, few children will get the chance to climb to a higher rung on a country’s income ladder than that occupied by their parents. So, income inequality remains high and social mobility remains low, transmitting inequality across generations, exacerbating the inequality of opportunity.

Three kinds of preservation forces perpetuate social immobility in middle-income countries, shutting out talent from economic creation. The first force is norms—biases that foreclose or limit opportunity for women and other members of marginalized groups. Next are networks—above all, family connections. And the last force is neighborhoods—regional and local disparities in access to education and jobs.

This is a very important insight to be kept in mind. Developing countries, and more so large ones like India, have little chance of sustained growth without broadening the base of those participating productively in the economy. This goes beyond firms and individuals to include gender, regions, castes, and religions.

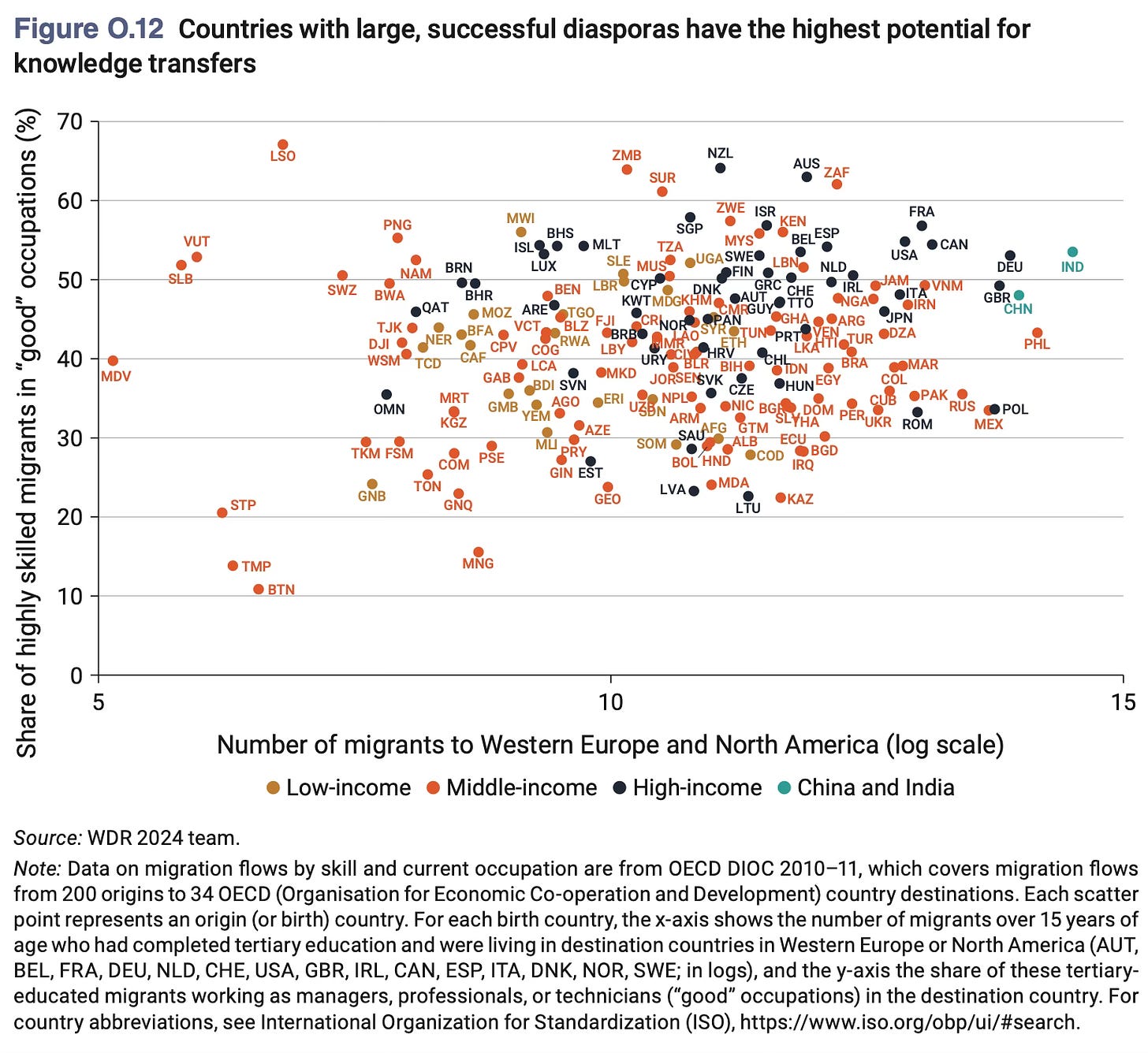

The report also points to the value of diaspora to a country’s growth prospects. An area where India appears well placed to capitalise is in the knowledge transfers from its vast diaspora. On this issue, it would be useful to cut through the clutter and get a sense of how much its large highly skilled and influential diaspora in the US, especially those in the highest echelons of finance and technology, have uniquely engaged with the Indian economy. What have been their contribution, over and above what would have happened anyways given the size of the Indian economy and its recent growth trajectory? What are the signatures of such engagement? How much of the high net-worth wealth and high-skill entrepreneurship have found their way back to investment and business creation in India?

While there are no studies that indicate so, despite its very large highly skilled and influential diaspora in the US, I cannot think of much by way of direct benefit to the Indian economy from the diaspora by itself. This contrasts with China, where many of the large manufacturing and industrial giants of today emerged from entrepreneurs who studied and worked in the US and elsewhere and returned to their homeland. As an illustration, while high levels of US corporate world is populated by a disproportionately high share of talented Indians, it’s striking that there are hardly any Chinese at those levels. Is it the case of the Chinese counterparts choosing to return to work in their country?

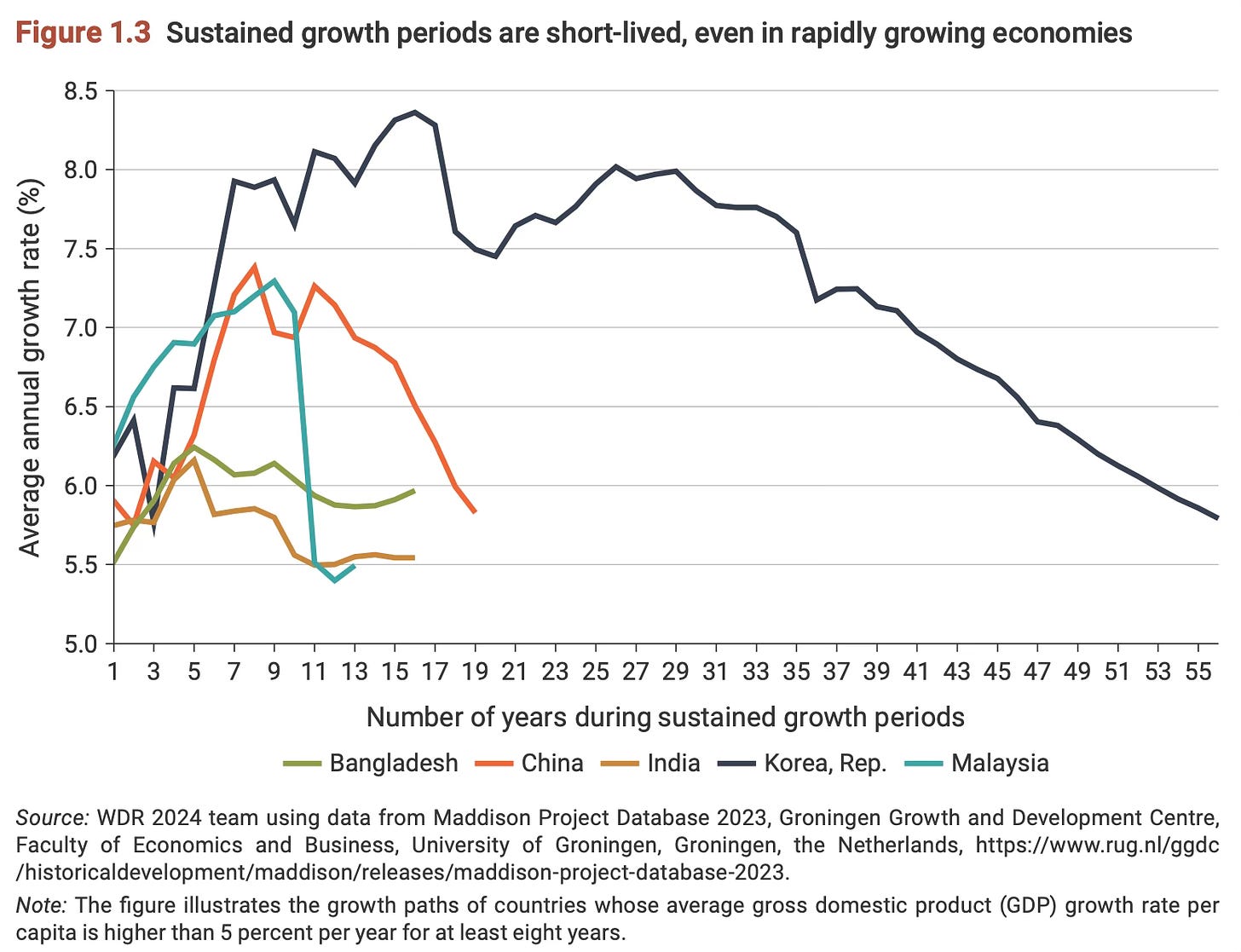

The report shows that sustained growth episodes are short. And India’s has so far been a lot shorter than that of others.

Now some critical observations about the findings in the report:

1. For a start, India’s current challenge is not so much escaping the middle-income trap as crossing even the upper middle-income threshold. The same is the case with most of the other large middle-income countries. By positing the middle-income trap, we are getting far ahead of the game.

2. I’m not sure about this

It is unlikely that industrial policy will enable countries to leapfrog from an investment- and manufacturing export–driven model to an innovation-oriented model or services-led model of economic growth. The development literature is littered with reports recommending a leap from investment to innovation, skipping the stage of painful reforms to attract foreign investment and ideas.

I’m not sure whether this argument has any empirical basis. There’s a strong element of ideology here, one where the orthodoxy of openness to foreign investment must be qualified with foreign investment that’s contingent on technology transfers and significant value addition.

This becomes especially important given the presence of China and its beggar-thy-neighbour industrial policy. In fact, I’ll venture out and argue that instead of accusing developing countries of not pursuing orthodox openness, the WDR should be accusing them of pursuing openness which does not place adequate safeguards against the decimation of local manufacturing bases by cheap Chinese imports. As I have blogged here, the problem of gradual destruction of the domestic manufacturing base arising from openness to cheap Chinese imports is a major problem facing developing countries today.

To put the China issue in perspective and the near impossibility of competing with them in many areas, consider this.

Starting production of solar panels in India from raw materials, such as quartz minerals, would be at least 40 per cent more expensive than in China. This cost difference reduces to 25 per cent if he uses imported polysilicon wafers and decreases to 3 per cent if he uses solar cells imported from China… producing solar modules from raw materials is too costly… This is similar to India’s smartphone sector, which relies on imported subassemblies, and the electric vehicle (EV) battery industry, which depends on imported lithium cells. Most manufacturing happens abroad in both cases, and more than 85 per cent of the components are imported. The high-cost difference between India and China is partly due to India’s higher cost of production inputs and China’s subsidies for its firms. For example, in India, the capital cost for businesses is 9-10 per cent, compared to 4-5 per cent in China. Industrial electricity in India costs $0.08 to $0.10 per kWh, while in China, it’s $0.06 to $0.08.

3. A related point made in the report is that about contestability of markets

Contestable markets—and the institutions that enable them—are vital for middle-income countries that aim to become global supplier and sustain rapid economic growth through sophistication and scale… A key part of contestability is openness to foreign investors and global value chains that give domestic firms access to larger markets, technology, and know-how and allows them to add value and grow. And they are encouraged to make use of that access, thereby exposing domestic firms to competition, but also inspiration, from international firms that operate at or near the global technology frontier. Firms at home can seize the opportunity to infuse technology, increase the sophistication of their operations, and scale up, or they can keep doing business as usual and be eased out.

Again, there’s a nuance missing. Yes, contestability and competition are essential. But it’s one thing to open the country to foreign investments but an altogether different thing to open up for imports. While contestability arising from trade liberalisation invariably follows the opening up, the same cannot be said about investments. Investment liberalisation takes time and effort to realise actual investments, if at all. FDI does not come merely by opening up the economy and requires efforts at multiple levels to relax entrenched economic and other constraints. Further, as developing countries are finding out, contestability arising from trade liberalisation is double-edged in so far as it ends up swamping the country with cheap Chinese products and destroying the local industry.

The examples of how Chilean and European companies in the period from 2000-07 benefited from Chinese imports are deceptive. For one, the Chinese competition was in its early stages then and not distorted to the same extent as now by subsidies. Besides, the Chinese competition then was in the less sophisticated products. And the European companies engaged from a position of high competitiveness given their strong manufacturing base. The situation is very different today and in the context of countries like India.

4. The report uses the Schumpeterian framework of creative destruction and the role that new entrants can play in triggering competition, creating value and displacing incumbents.

There’s nothing inevitable or market-driven about this dynamic. Economies can get stuck in multiple equilibriums. Instead, this dynamic requires an active government role in co-ordination and relaxation of constraints.

Take the example of India’s textiles, footwear, food processing, consumer electronics and durables, capital equipment, automobile, and solar manufacturing sectors. While there are a few large domestic firms in some of these sectors, I cannot think of entrants over the last twenty years that have grown to become dominant firms in their sectors, leave aside become large exporters. How many entrants have emerged as competitors in India’s entire consumer durables or capital equipment or textiles or footwear market? How many entrants are there to validate the Aghion-Howitt thesis that they create value, displace incumbents, and become protagonists of economic growth?

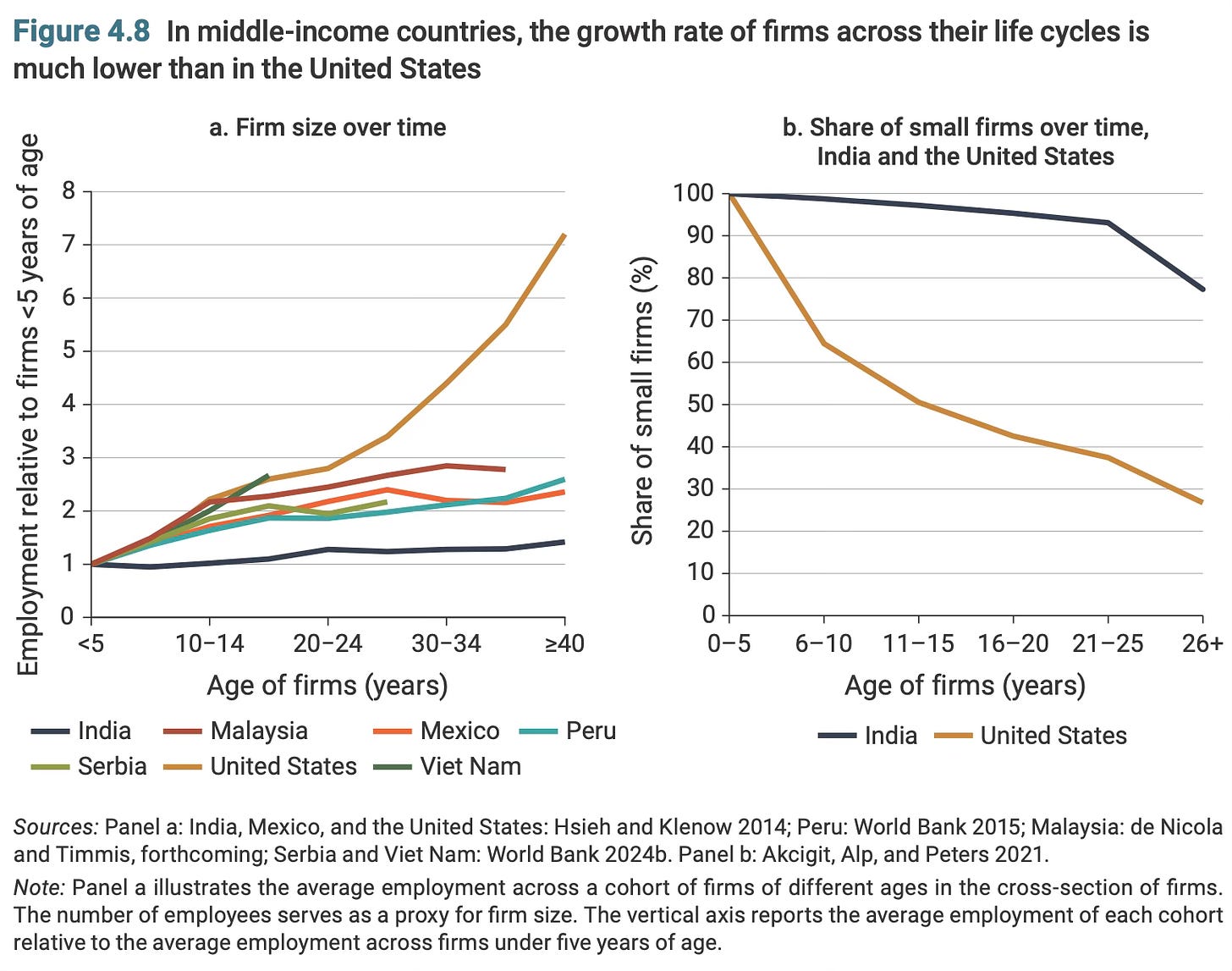

The creation and innovation parts are very hard. In an acknowledgement of the problem, the report points to one of the most important problems with the landscape of manufacturing and industries, the low rates of productive business creation and deficient dynamism among incumbents.

The forces of creation are weak in middle-income countries. In India, Mexico, and Peru, for example, if a firm operates for 40 years, it will roughly double in size. In the United States, the average firm that survives that long will grow sevenfold. For firms in middle-income countries, this implies a “flat and stay” dynamic: firms that fail to grow substantially can still survive for decades. By contrast, for US firms the dynamic is “up or out”: facing intense competitive pressure, a few entrepreneurs will expand their businesses rapidly, while most others will exit quickly. Among the majority who exit the market, many will become wage earners at the most flourishing firms.

In keeping with the flat and stay dynamics, firms in India, Mexico, and Peru tend to remain microenterprises: nearly nine-tenths of firms have fewer than five employees, and only a tiny minority have 10 or more. The longevity of undersize firms—many of them informal—points to market distortions that keep enterprises small while keeping too many in business. For example, a high regulatory cost attached to formal business growth may inhibit an efficient firm from gaining market share and driving out inefficient competitors. Such policy-induced distortions in middle-income countries result in misallocated resources, hampering creation and infusion at scale.

Given this, I’m not sure also about the third-generation Schumpeterian Akcigit-Kerr view of incumbents being spurred by competition from new entrants and foreigners, and increasing their productivity and innovating to the technology frontier. This view sees incumbent market leaders as bringing scale and advancing domestic industry towards the technology frontier.

As I have blogged here, India’s private sector incumbents (and startups) have been remarkably slow and deficient in operating at the technology frontier across sectors. This lag is reflected in their very low R&D spending compared to peers even among the larger middle-income countries. In fact, scale manufacturing (this and this) has been an enduring deficiency of India’s business landscape, and remains so.

For example, despite the head start enjoyed in pharmaceuticals, the Indian drugs industry has not managed to move up to pharmaceuticals value chain to formulations and drug discovery, much less emerge as large contract manufacturers of APIs of the kind their Chinese counterparts have become. The behemoth IT firms have struggled to come up with any major software products and are virtually absent in cutting-edge areas like cloud computing, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and data analytics. The established domestic manufacturing firms in areas like capital equipment, automobiles, and consumer durables operate distant from the global technology frontier. Finally, even the much-hyped startup ecosystem struggles to innovate at the technology frontier.

In areas like consumer electronics manufacturing, it has taken active industrial policy and nudging by the government through the likes of Make in India and Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme for even the limited breakthroughs that have been made.

Similarly, there’s nothing inevitable about the movement up the value chain. So, for example, the dynamics of market forces will not gradually push India up the manufacturing value chain of mobile phones or solar panels in terms of increasing domestic value addition. The Indian mobile phone and solar panel manufacturing industries can remain stuck in the low-value assembly part of the value chain for a long time. As the experience of the North East Asian economies shows, there’s a need for active industrial policy to guide and push industries and businesses up the value chain.

Orthodox economists will blame entry barriers and other constraints that prevent competition for the above problems and failures. But in a reasonably well-managed, macroeconomically stable, continental-sized economy, as India is, even with all constraints, there should have been at least a few Schupeterian examples. So what gives?

One explanation is that ideas and their adoption will be contingent on real-world challenges and constraints, many of which will remain no matter what. In these circumstances, active government engagement will be an essential requirement even with the Schumpeterian framework.

5. An area of ideological faith among opinion makers and commentators everywhere is the belief that there are large amounts of foreign and domestic private capital willing to invest in developing countries. The argument goes that it’s not so much the capital availability per se, but the absence of good projects and investment opportunities.

Instead, a more appropriate framing would be that private capital, debt and equity, and especially foreign capital, demand a rate of return that’s too high to be borne by the vast majority of investment opportunities available in any economy. There’s a circularity here - private investments are constrained by a lack of investment opportunities, and investment opportunities are limited by the prohibitive cost of capital and return expectations.

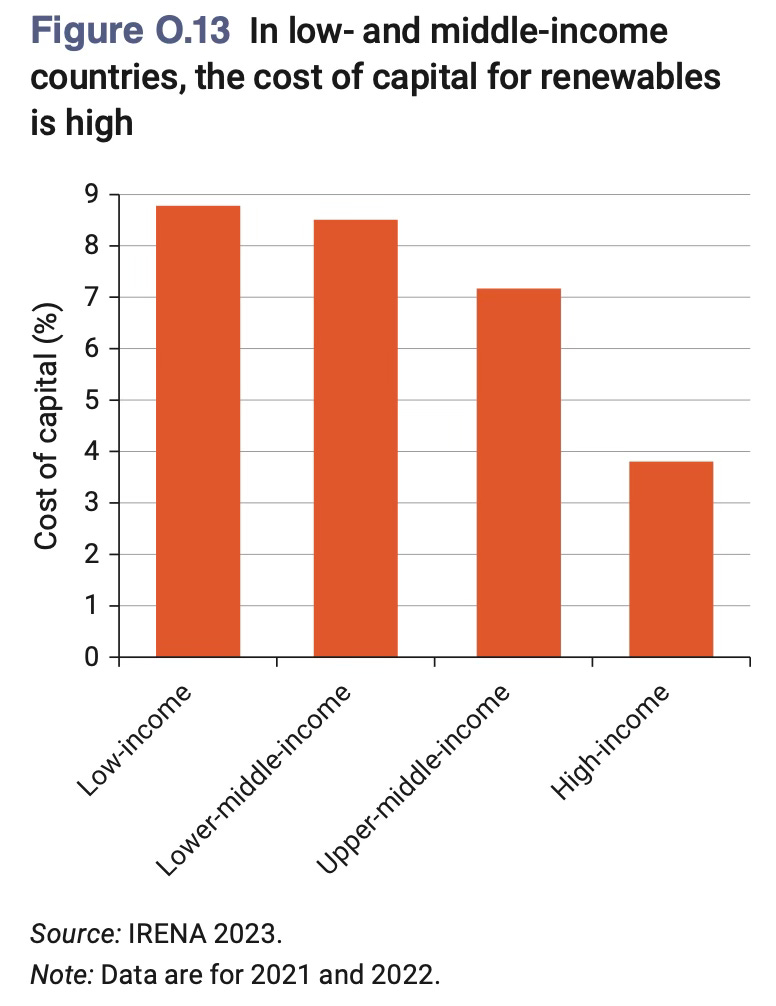

It can therefore be said that one of the biggest impediments to accelerated investment in developing countries like India is their cost of capital and high return expectations of investors. As the graphic below shows, the cost of capital in low-income and lower-middle-income countries is more than double that in high-income countries. This will be higher once you add the layers of country and currency risks that foreign capital must bear. This 8-10 percentage points differential is huge and renders many investments unviable.

Unfortunately, there are very few straightforward measures to bridge this gap. And, as I blogged here and here, the few that can bridge the gap somewhat require deep-rooted plumbing reforms.

Projects and ideas/opportunities that routinely attract investments in developed countries struggle to find investors in developing countries. And that will remain a reality until those countries reach similar stages of development and incomes.

6. The report sees the climate change crises as an opportunity for developing countries. Yes, in theory, there’s an opportunity in so far as it provides these countries new investment opportunities and that too which can operate at the technology frontier. But in practice, this opportunity can be misleading.

Consider the example of India’s solar industry. While the country has expanded its renewables generation capacity, it has struggled to gain even a toe-hold on solar and wind power manufacturing. And this is despite the leverage provided by the country’s massive capacity expansion potential. Econ 101 tells us that this context is ripe for the creation of domestic manufacturing facilities. Clearly, contrary to what’s being suggested in the report, openness and markets by themselves will not result in foreign investment and technology transfers. This example holds for several industries.

Then, there’s the issue of the costs associated with the green transition. I have written here in detail highlighting the serious limits to developing countries being able to use the green transition as an opportunity to boost their economic growth.

In conclusion, developing countries face a Hobson’s choice. On the one hand, trade openness threatens to swamp the country with cheap Chinese imports, and destroy the local industry. The idea of import competition to improve the competitiveness of the domestic industry falls apart when faced with cheap Chinese imports. On the other hand, investment openness is a long route to change with several capabilities requirements and the national security vulnerabilities of relying on Chinese FDI, whose coming itself is questionable.

I’ll argue that developing countries should pursue a three-pronged strategy, one shorn of any ideology or orthodoxy and which is grounded on strict prudence and realism. It’s also the one that Joe Studwell has very nicely articulated as the ingredients of the successful North East Asian economies.

One, internally they should pursue an industrial policy that promotes domestic industries and businesses and disciplines them with subsidies and concessions that are linked to export competition. This would necessarily involve picking specific sectors and less so, firms, and supporting them and calibrating policy continuously to ensure that they keep moving up the value chain. This industrial policy should be cautious of being captured by domestic vested interests.

Two, externally they should encourage foreign investment, but at terms that come with value addition and technology transfer. This would require policies that explicitly encourage joint ventures with big domestic companies, mandate domestic content requirements in the manufacturing investments and technology transfer conditions, and provide incentives that are linked to exports.

Three, trade policy should be responsive to the threat posed by cheap Chinese imports and erect tariff and non-tariff barriers against them. While there’s a thin line here between protectionism and capture by domestic vested interests, this risk cannot allow the domestic industry to be invariably destroyed by cheap Chinese imports.

There are serious limits to how smaller and even medium-sized countries can pursue such a strategy. But for large economies like India, there’s ample space to pursue the three-pronged approach indicated above. The danger though is its capture by vested interest and the lack of adequate state capabilities to implement them effectively.

No comments:

Post a Comment