1. On mangoes

India is the world’s biggest mango producer, with volumes greater than the next nine growers combined, according to Tridge, a data firm. Yet its share of the global export market by value is a meagre 7%. Mexico, which produces a tenth as much as India, accounts for a quarter. The reasons are many, writes Sopan Joshi in “Mangifera Indica”, a new book about mangoes. Chief among them are the delicate nature of the fruit, poor growing practices in India and strict standards in Western markets.

2. Interesting fact about the state where US companies are getting incorporated, Delaware stands out with over 70%.

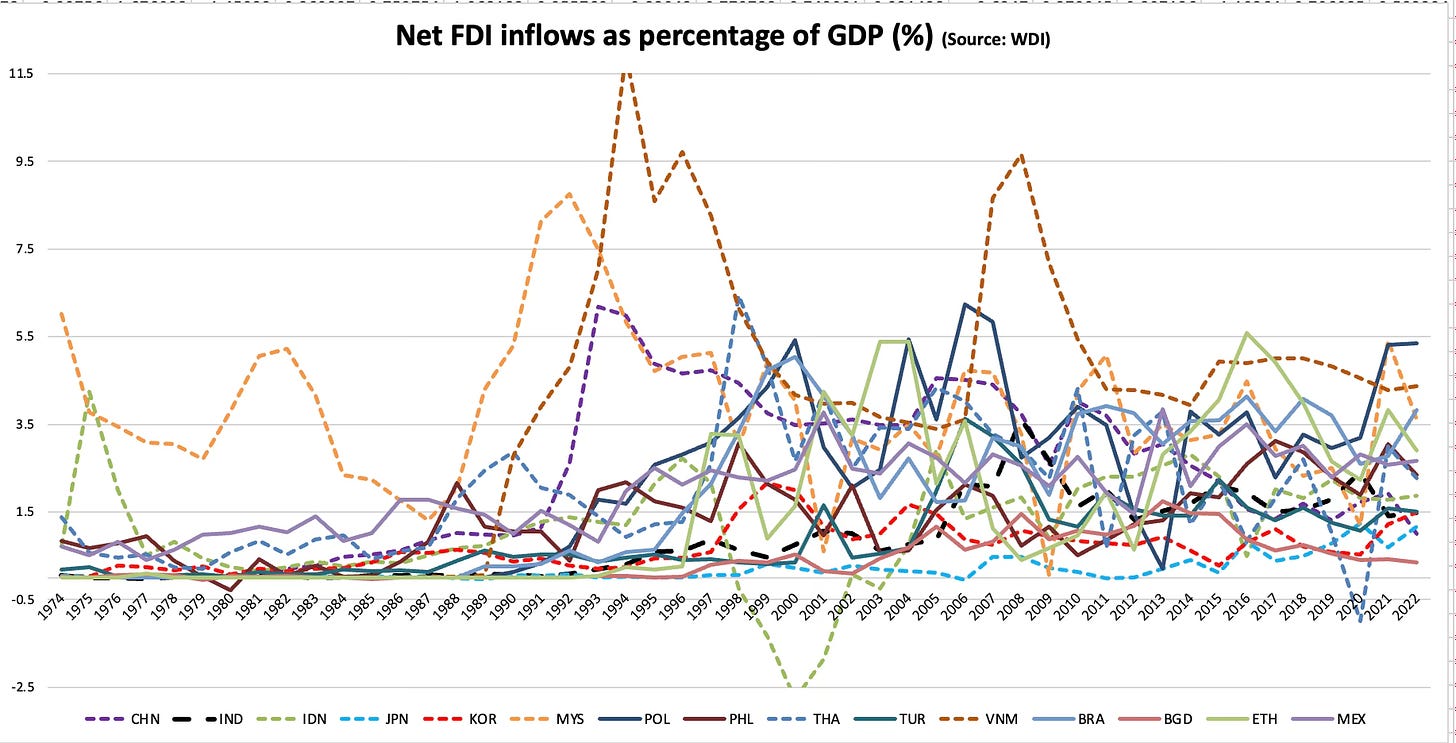

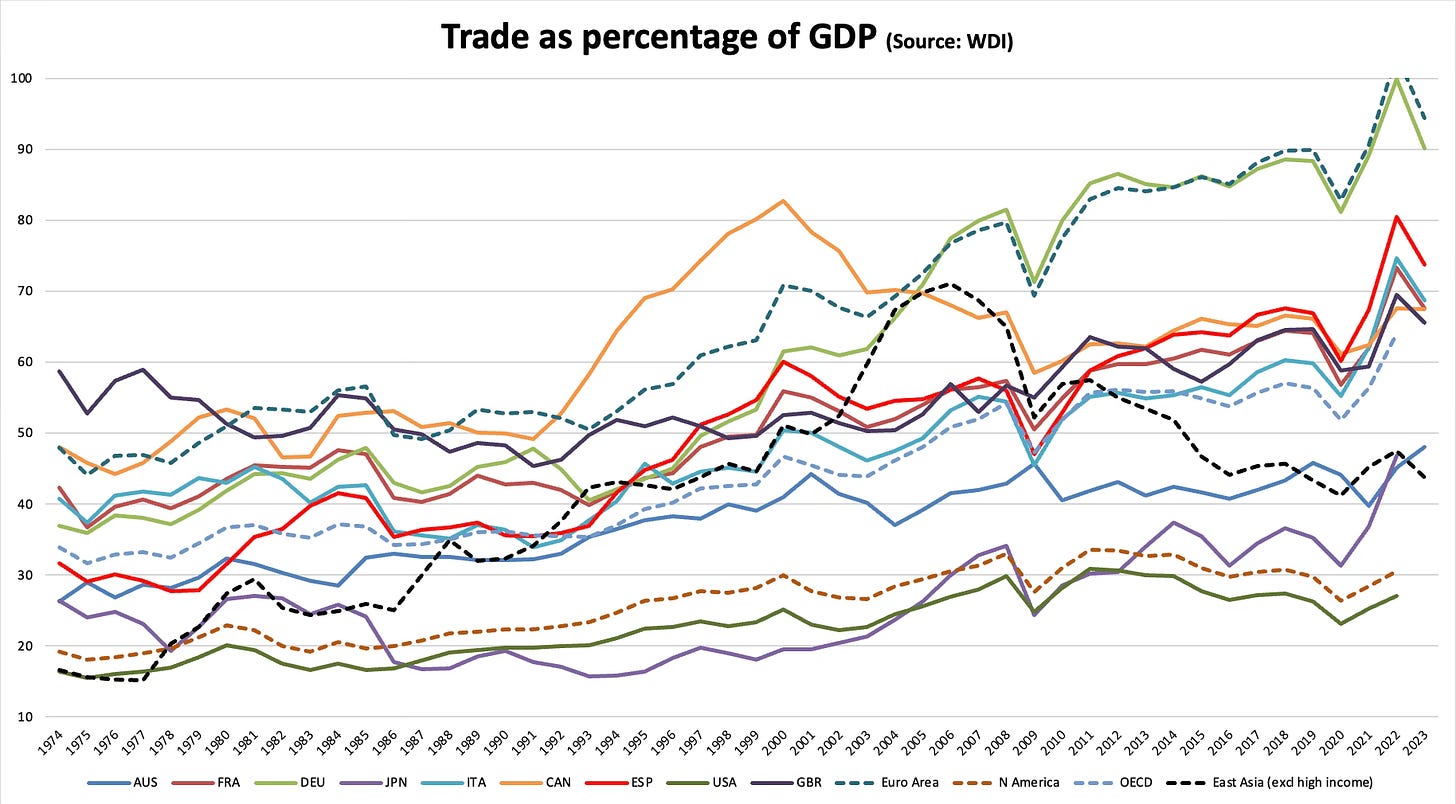

3. Data does not bear out signatures of deglobalisation.Since early 2019 the combined worth of the tech giants (Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, and Apple) has more than tripled, to $11.8trn. Add in Nvidia, the only other American firm valued in the trillions, thanks to its pivotal role in generative artificial intelligence (ai), and they fetch more than one and a half times the value of America’s next 25 firms put together. That includes big oil (ExxonMobil and Chevron), big pharma (Eli Lilly and Johnson & Johnson), big finance (Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase) and big retail (Walmart). In other words, while the tech illuminati have grown bigger and more powerful, the rest lag ever further behind...Since 2019 the five tech giants and Nvidia have doubled their capital expenditures, to $169bn last year. Tot up the 25 next firms’ capex and it was just $135bn—up only 35%. As for brain power, over the same period, the big six added 1m jobs, doubling their headcount. No one can accuse them of resting on their laurels. They have invested in ai startups, ploughed fortunes into building large language models and, in Meta’s case, created open-source offerings that almost anyone can use. This year they are doubling down on their ai spending if only to protect their flanks.

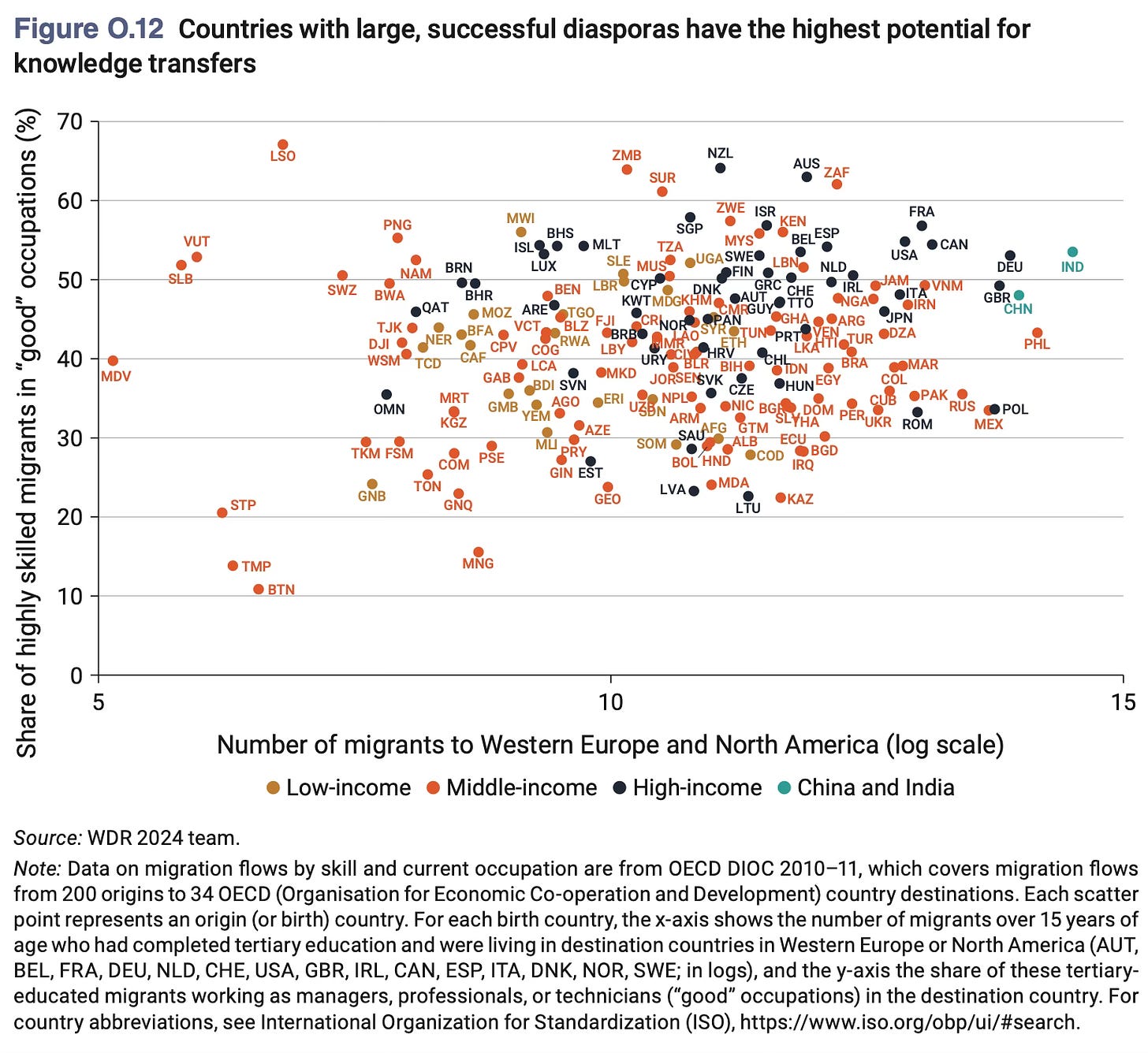

5. Striking facts about the importance of immigrants to the US economy.

Immigrants are 14% of the population in America, 16% of inventors and directly produce over 23% of innovation, measured by patents, patent citations and the economic value of those patents, the authors estimate. Taking into account how they make their native-born collaborators more productive, they are responsible for a staggering 36% of total innovation.

Researchers at Peking University... analysed surveys of household spending before and after the tutoring ban and found that low- and middle-income families were, on average, spending less on after-school education. The richest families, though, were spending more. Tutors were still active. But because they were acting illegally, they charged more, pricing most people out.

7. Very good summary of the performance of State Bank of India under Mr Dinesh Khara who stepped down as CMD after four years. These are very impressive numbers

Between October 7, 2020 and last week, SBI stock has delivered a 328.36 per cent return to investors, compared to Bank Nifty’s 122 per cent return and Bankex’s 122.9 per cent. During this time, the Nifty returned 111.4 per cent, and the Sensex 103.3 per cent. The largest private bank, HDFC Bank Ltd, saw its stock rise 39.9 per cent, while ICICI Bank Ltd rose 214.6 per cent in this period. For SBI, the return on assets (RoA) moved from 0.43 in September 2020 to 1.10 in June 2024. During this period, return on equity (RoE) increased from 8.94 to 20.98, and earnings per share (EPS) from 19.59 to 76.56... While the bank’s assets have grown over the past three-and-a-half years at a compounded annual growth rate of 10.56 per cent, from Rs 43.58 trillion to Rs 61.91 trillion, its gross non-performing assets (NPAs), as a percentage of total assets, have more than halved, from 4.77 per cent to 2.21 per cent. After provisioning, net NPAs have decreased from 1.23 per cent to 0.57 per cent. Meanwhile, the net interest margin (NIM) — loosely the difference between what it spends on deposits and earns on loans — has risen marginally from 3.31 per cent to 3.35 per cent.

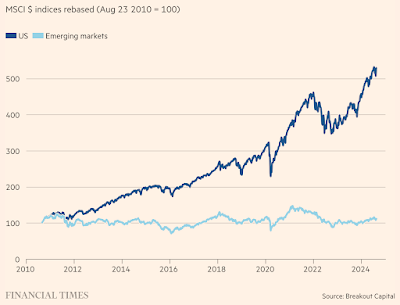

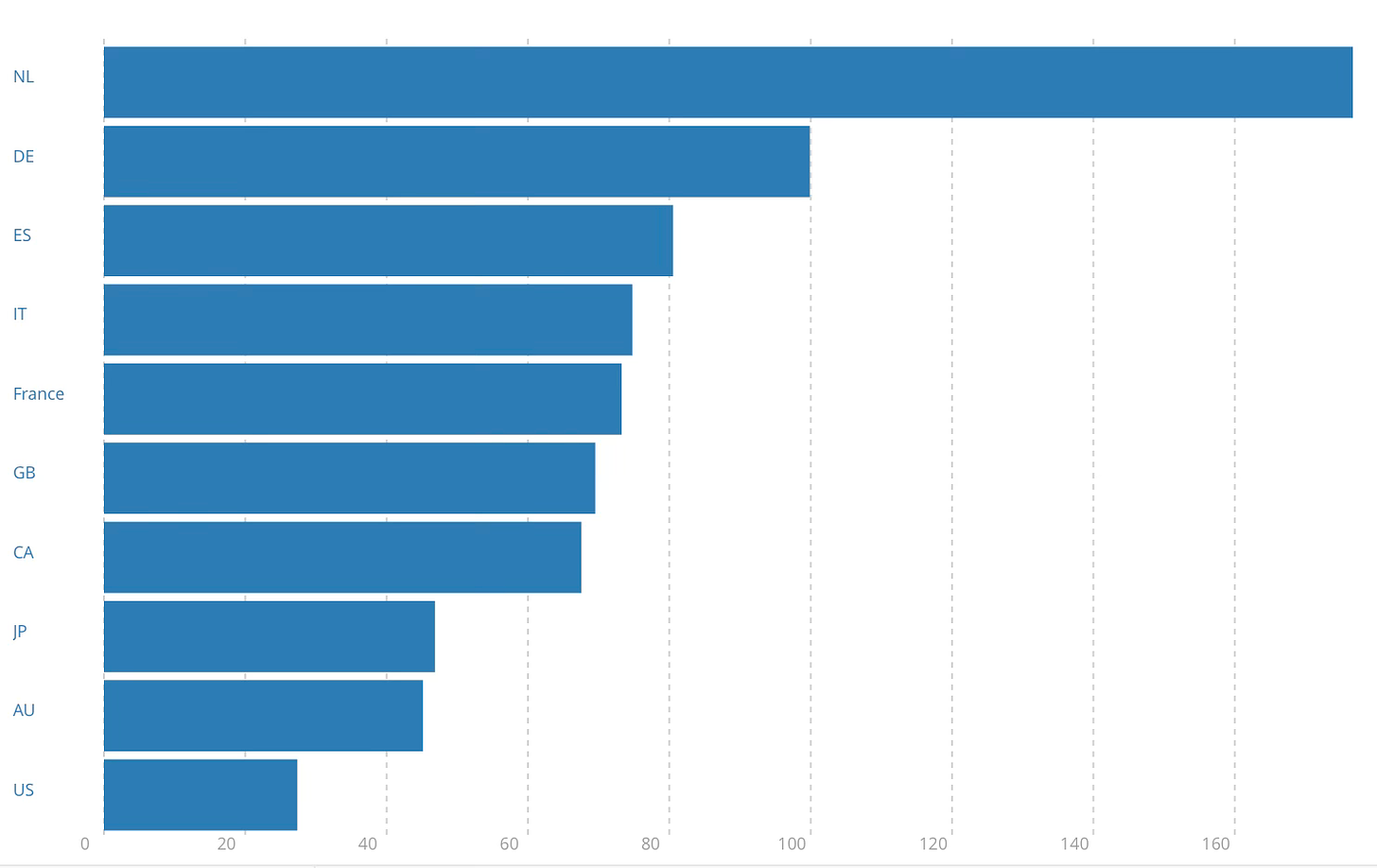

At the beginning of the 20th century, the US accounted for about 15 per cent of world market capitalisation, second only to the UK, which was at 24 per cent. By 1910, the US had crossed the UK to become the largest equity market in the world. It has since retained this title, unchallenged except for a brief period in the late 1980s when Japan held the top position. Japan peaked in 1989 at 40 per cent of world market capitalisation, while the US was second at 29 per cent. Today, the US remains unchallenged, accounting for more than 62 per cent of world market capitalisation. The next largest market is Japan at 6 per cent, followed by the UK at 3.7 per cent, and China at 2.8 per cent (all based on the FT World Index and free float adjusted). Just 12 markets, including India, account for 90 per cent of world equity market capitalisation. Looking at the longest available data series on equity market performance (1900-2023), spanning 124 years, we see that the US has delivered the best real returns, with an annualised rate of 6.5 per cent. The only market even close is Australia at 6.45 per cent in dollar terms, though there is no comparison in terms of size or absolute market capitalisation created. The UK has delivered 4.9 per cent real return, while Germany and France lag with return profiles of only 3.3 per cent and 3.16 per cent, respectively. Japan delivered 4.2 per cent (all in dollar terms). Compared to the 6.5 per cent real return of the US, the world ex-US, delivered 4.3 per cent, a gap of 2.2 percentage points compounded over 124 years. This leads to huge differences in terminal value. The US has undoubtedly been the right place to invest. If an investor had been exclusively invested in the US for the entire 124 years, their return would have turned one dollar into $2,443 in real terms. The same dollar invested in non-US markets would have grown to only $191, not even one-tenth of the US investment portfolio.

And about India

Over this 30-year period (ending July 30, 2024), MSCI India has delivered a nominal annualised return of 8.65 per cent in dollar terms, compared to 5.3 per cent for MSCI.

11. FT has a nice report from Panyu, a suburb in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, which is nicknamed the "Shein village" for its centrality in the retailer's business. The $66 bn valued firm, due for listing at the London Stock Exchange, has shaken up fast fashion with its $5 dresses and $2 T-shirts.

The article captures the reasons for Shein's competitive advantage.

But going to the heartland of Shein’s supply chain, it was clear that its low prices are in spite of, not because of labour costs, which have been rising in China as the working-age population shrinks and young migrant workers shun factory jobs for the lower-paid service sector. Factory workers that source to Shein typically get paid between Rmb7,000 ($982) and Rmb12,000 monthly, depending on how many clothes they finish. By contrast, the average wage for other blue-collar workers in the area is between Rmb5,500 and Rmb6,500. Part of the reason the clothes are cheap is, well, because they are cheap. One factory manager held up a baggy dress — probably destined for the US or UK — and joked that she would never sell such low-quality clothes to a more discerning Chinese clientele. She says she uses cheaper fabrics for Shein orders than for Alibaba’s Taobao, because the domestic platform gives more money to the factories to cover their costs.Shein has also cut out expensive middlemen by shipping goods directly from warehouses in China to shoppers in the west — a model that has the added benefit of the great majority of its packages bypassing import duties. Panyu highlights the attraction of Chinese manufacturing. Like other manufacturing hubs specialising in anything from socks to sex toys to steel pans, it has the entire supply chain concentrated in one district. That means factories can within half an hour place an order, take delivery of fabric or get an engineer to fix sewing machines with components made nearby... China’s migrant worker population also brings it an edge. While in Vietnam and Bangladesh workers tend to return home to their families at night, the labourers in Panyu sleep in nearby dormitories, cutting down commuting time and meaning they can work longer hours if a large order arrives.

12. Good graphic that shows how the markets over-react to economic news.

Robert Armstorng writes in Unhedged in FT.

Here is the futures market’s expectations for what the federal funds rate will be in December 2024, as well as the Fed’s projections from its quarterly summary of economic projections (the last SEP was released in early June)... One cannot help but notice the pattern of overreaction and correction on the market side. It’s like a car on an icy road. There is a whole sub-industry — Unhedged is part of it — that spends its time arguing about why the Fed is too loose or too tight. But in retrospect we probably overstate the importance of the current and expected level of rates. What matters is keeping expectations anchored on the one hand, and avoiding an unnecessary recession on the other.

BCG has admitted it paid millions of dollars in bribes to win business in Angola, and agreed to give up more than $14mn in profits from contracts it won with the country’s economy ministry and central bank. The consulting firm sent money to offshore accounts controlled by middlemen connected to Angolan officials and members of the ruling political party, according to a US Department of Justice investigation made public on Wednesday. The bribes were paid by BCG through its office in Lisbon, Portugal, between about 2011 and 2017, the DoJ said... BCG agreed to pay an agent with ties to Angolan officials between 20 per cent and 35 per cent of the value of the contracts it won, routing the money through three different offshore entities, the DoJ said... The period of the bribes coincided with the end of the rule of the late José Eduardo dos Santos, who stepped down in 2017 after 38 years in power... In total, BCG won 11 contracts with the Angolan ministry of economy and one with the National Bank of Angola over the years in question, bringing in $22.5mn in revenue. The firm will return the $14.4mn in profits that the contracts generated.

14. But KPMG and UK validates the adage that the more things change, more they remain the same

KPMG has won a UK government contract worth up to £223mn to train civil servants, the second-largest public sector contract awarded to the Big Four firm and agreed before the Treasury set out plans to drastically reduce Whitehall’s reliance on external consultants last month. Under the 14-month deal with the Cabinet Office, which commenced this month, the consulting firm will manage learning and development services across Whitehall, including overseeing courses on policymaking, communications and career development. The maximum value of the contract represents close to 8 per cent of KPMG’s annual UK revenues, making it the second-biggest public sector contract awarded to the firm, according to data provider Tussell. The most valuable piece of public sector work awarded to KPMG was a separate learning and development deal with the Cabinet Office worth £237mn, Tussell said. That four-year contract, which expires in October, involves the firm overseeing technical training for civil servants, such as professional qualifications. The lucrative contracts demonstrate a return to positive relations between the government and KPMG. The Big Four firm stopped bidding for UK government contracts in 2021 following a threat by the Cabinet Office to ban it from winning public sector work after its involvement in a series of scandals. It resumed bidding for public sector contracts in 2022. They also come as the Labour government has committed to halving Whitehall spending on consulting firms during this parliament, with chancellor Rachel Reeves last month ordering departments to stop all “non-essential spending” on external consultants. A government spokesperson said the KPMG contract was agreed before July’s general election. The Conservative party also pledged to halve Whitehall spending on external advisory firms in its election manifesto. The Treasury estimated in July that reducing the government’s reliance on advisory groups would save £550mn in the 2024-25 financial year and a further £680mn in 2025-26, when the policy to halve total spending on consultants came into force. The savings would, in part, help fund significant public sector pay rises, the chancellor said.

15. Very good article on how Nvidia is working to protect its domination of the high-end chips design market.

The key issue is when the main focus in AI moves from training the large “foundation” models that underpin modern AI systems, to putting those models into widespread use in the applications used by large numbers of consumers and businesses. With their ability to handle multiple computations in parallel, Nvidia’s powerful graphical processing units, or GPUs, have maintained their dominance of data-intensive AI training. By contrast, running queries against these AI models — known as inference — is a less demanding activity that could provide an opening for makers of less powerful — and cheaper — chips... Nvidia’s lead in this newer market already looks formidable. Announcing its latest earnings on Thursday, it said more than 40 per cent of its data centre sales over the past 12 months were already tied to inference, accounting for more than $33bn in revenue... But how the inference market will develop from here is uncertain. Two questions will determine the outcome: whether the AI business continues to be dominated by a race to build ever larger AI models, and where most of the inference will take place. Nvidia’s fortunes have been heavily tied to the race for scale... Yet it is not clear whether ever-larger models will continue to dominate the market, or whether these will eventually hit a point of diminishing returns. At the same time, smaller models that promise many of the same benefits, as well as less capable models designed for narrower tasks, are already coming into vogue.Meta, for instance, recently claimed that its new Llama 3.1 could match the performance of the advanced models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4, despite being far smaller. Improved training techniques, often relying on larger amounts of high-quality data, have helped. Once trained, the biggest models can also be “distilled” in smaller versions. Such developments promise to bring more of the work of AI inference to smaller, or “edge”, data centres, and on to smartphones and PCs... The range of competitors with an eye on this nascent market has been growing rapidly... The data centre market, meanwhile, has attracted a wide array of would-be competitors, from start-ups like Cerebras and Groq to tech giants like Meta and Amazon, which have developed their own inference chips. It is inevitable that Nvidia will lose market share as AI inference moves to devices where it does not yet have a presence, and to the data centres of cloud companies that favour in-house chip designs. But to defend its turf, it is leaning heavily on the software strategy that has long acted as a moat around its hardware, with tools that make it easier for developers to put its chips to use.

16. Finally, Japanese startup scene is finally waking up after long drawn persistent efforts by the Government.

The ambitions are charged with the faith that start-ups can drive GDP growth and productivity, rescue the country from a long-term innovative tailspin and channel its talent in the right — or at least less wrong — direction. It has a belated, even desperate feel to it, but start-ups now seem to be Japan’s core industrial policy. The extent of both central and local government backing is striking. In addition to the many subsidies now on offer, state-backed entities like the Japan External Trade Organization have been drafted into the effort by providing acceleration programmes and other services. The government-backed Japan Investment Corporation has invested close to $1bn into 32 private venture capital funds. Under heavy government pressure, Japan’s three biggest banks have recently begun offering start-ups loans backed against current and future cash flow, breaking their long, entrepreneurialism-crushing habit of only lending against hard collateral such as the property of a would-be start-up founder. By many metrics, all this is working. In 2013, said the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in a recent paper, the total investment into start-ups in Japan was a minuscule $600mn; a decade later, that had risen to over $6bn. Between 2014 and 2023, the number of university start-ups more than doubled to 4,288, with METI research showing that roughly half of university students would prefer to start their careers at one.