A constant theme of many posts in this blog is the lack of dynamism, the absence of scale manufacturing, and the deficit of genuine entrepreneurship in corporate India. More than three decades after liberalisation, corporate India's balance sheet is nothing to shout about.

Despite the massive economy and even three decades after liberalisation, corporate India suffers from an acute lack of world-class companies and brands in sectors like consumer durables and fast-moving consumer goods. Across sectors, Indian companies have made little headway outside India in the competitive and mature western markets. Even in sectors like pharmaceuticals and software, where the country's companies have had a head start, there's little to show for the global stage at the upper end of the value chain. There's not one Indian engineering company that's a top global manufacturing firm. India's much-hyped software industry continues to remain stuck at the lower end of the value chain and has struggled to make any world-class software products.

The country's high profile start-ups are faring no better than their predecessors. They are stuck chasing copycat innovations instead of being pioneers in cloud computing, IoT, data analytics, artificial intelligence and robotics. Despite having several serious development challenges in areas like health, education, nutrition, e-governance etc, and the associated market possibilities, there's nothing on the landscape with any promise to be able to make a meaningful impact on any of these problems. The story of the country's hyped Edtech companies that's currently playing out is a reminder.

For a continental economy with nearly 1.5 billion people and 60 million plus "entrepreneurs", it violates even statistical principles that we've not been able to produce even a few world-class companies or consumer brands or software products. At the risk of exaggeration but to make the point, every other major economy has something world-class on its corporate sector balance sheet. Even Bollywood remains stuck behind the likes of Korean movies and K-pop, and Brazilian telenovelas in making an impact in western markets. I could not identify even one Indian cuisine restaurant among the 139 restaurants listed as 3-star by the Michelin Guide, though it covered every other major global cuisine.

Now you could turn around and argue that serving the Indian market suffices, and there are large Indian companies across sectors that serve the Indian market. Corporate India making for India! Though there are several responses to the problems with that view, it's not relevant to the issue discussed in this post.

In this context, I came across Rama Bijapurkar's oped in Business Standard where she makes the point that instead of fretting about consumer demand, commentators should be worried about the inadequate supply side in the Indian economy. She makes the point that large companies serve the top 20% market (at the most) and the bottom 80% are served largely by the informal market. She exhorts corporate India to seize the opportunity and invest in this market segment, and feels that e-commerce marketplaces offer great promise.

She writes,

It is now the supply side that ails and lags. It needs to find/rediscover its animal spirits to serve existing demand and stoke demand growth. The explosion of consumption down the income pyramid when the value proposition is right is demonstrated by UPI, Amazon, smart phones at the lower end, and digital entertainment, among others. Consumer India is underserved not only at the bottom end of the income spectrum but also in the middle and at the top end. It can easily absorb more D Mart-type value retail chains, more Bajaj Finance-type consumption financers, many more truly full-service and full-spectrum consumer durable retail chains, more “no-frills” airlines, many more business class seats at prices not distorted by demand — supply mismatches, more truly affordable housing, more organic food, more differentiated brands of personal wear and care across price points, more brands that emulate high-priced brands at a lower price-performance point, more toy brands at all price points, and a multitude of services of all kinds.Big Indian companies, typically listed or invested in by private equity with a view to list, and MNCs restrict themselves to serving the top of the income pyramid, (richest 20 per cent at most) with only a handful of notable exceptions. Their belief is that the remaining Indian consumer demand is not worthy yet of being acknowledged as “real, grown up” demand. This explains the limited number of consumer-facing companies listed among the top 200 companies, and only three of them having a turnover above $6 billion.

Large Indian suppliers have restricted themselves by waiting for the majority of Consumer India to cross a certain arbitrary threshold of income in order to qualify as real customers. This amounts to saying that it is the consumer who should grow her income to be able to afford the supplier’s high costs, rather than the supplier figuring out business models that deliver to her price-performance criteria while remaining profitable. India Inc is yet to build the confidence to invest significantly in the fifth-largest economy in the world, where over half the gross domestic product comes from household consumption. If choosing not to serve mass markets is the strategic choice large suppliers make, then their influence on policymaking should diminish accordingly.

The remaining 80 per cent of Consumer India is mostly served by domestic small suppliers and expedient imports pushed through wholesale trade. In the past, small suppliers equalled shoddy quality, poor features, and cheaper prices. Today, this supply segment has dramatically improved. As an example, there are 10 times more local and regional small fast-moving consumer goods brands than large supply brands, offering better customer-perceived value. The trouble with small supply is that it has little resilience to weather environmental turbulence, and little surplus to invest in scaling up and improving its offerings and operations to better serve mass-market Consumer India. They need enabling conditions to help more capable small suppliers perform better and grow larger, and not protection through tariffs and subsidies.

Finally she points to the promise of e-commerce business model in serving the mass market segment.

A very promising new kid on the supply block is the e-commerce marketplace emerging in every category. They aggregate small suppliers and give them opportunities and benefits well beyond what their size can afford, such as wider market access and other services that they would not otherwise be able to access. Policies that support more such marketplaces to bloom while curbing exploitative practices would be a win-win for supplier, consumer, and the country.

Creating even a D-Mart requires large and patient risk capital, apart from serious entrepreneurship. There are very few such entrepreneurs in India even on the less risky consumer business side.

Someone should study e-commerce transactions across all major platforms for 3-4 years and analyse the numbers of customers transacting, the nature of products being purchased, the nature of discretionary consumption goods, respective shares of lower priced and higher priced brands in the same good, the proportion of buyers purchasing discretionary consumption goods as against regular consumption goods, and so on. I’m sure it would reveal the true nature of the Indian economy.

This is a good article on the ‘paisa vasool’ business model of Indian IT companies.

What has let Indian IT majors stick with their ‘paisa vasool’ (value for money) model is that the growth in salaries for Indian engineers has not kept pace with the growth in our economy. This is most evident in the starting salaries being offered by our IT majors to fresh engineering graduates. These packages have remained more or less constant for almost two decades, with insufficient correction for inflation.

This article compares the Indian IT majors with Accenture, and how the latter has continuously seized opportunities to become a leader across segments.

Accenture Plc shared with investors its new strategy, “The Reinvention Phase”. Accenture calls the current demand for technology services the “Intelligent Reinvention”, which will be scripted by the growth of Cloud computing, AI and robotics, metaverse, and Quantum Computing. After offering services in the areas generally classified as social, mobile, analytics, and cloud (SMAC) over the decade, Accenture’s entire thesis rests on the premise that a foundation for the digital core has been built inside the technology landscape of companies. Pillars of smart cloud computing platforms, cybersecurity solutions, and other experimental technologies like artificial intelligence tools and metaverse can be laid on this Digital Core.

… not a single homegrown IT giant has publicly articulated how they expect to build on generative AI tools… Back in 2014, Accenture became the first technology services firm to quantify the digital business… The firm has more than doubled its revenue to end with $64.1 billion in the year ended August 2023. TCS, since it articulated digital business in 2015, has grown its revenue by 81%, while Wipro’s revenue has jumped 52%. Cognizant and Infosys have seen their revenue expand 44% and 78.5%, respectively, since the two companies first disclosed their share of digital business in 2017.

Accenture’s faster growth has been fueled by its rapid expansion in the cloud computing business (which has recorded a 36% compounded annual growth between 2012 and 2023) and building a new ad and marketing business under Accenture Interactive. Accenture Cloud ended with $32 billion, and Interactive had over $15 billion in revenue at the end of August 2023… the company is threatening the leaders in not one or two but three industries. A strong consulting practice now makes Accenture a competitor to management consulting firms dominated by McKinsey and Boston Consulting Groups. A strong interactive practice, which is the digital ad and marketing arm, has helped it challenge the pure-play ad firms, such as UK-based WPP and the French agency Publicis Group. Finally, Accenture continues to offer coders and do the IT infrastructure work, thereby taking on homegrown IT firms like Tata Consultancy Services and Infosys Ltd.

Update 2 (18.12.2023)

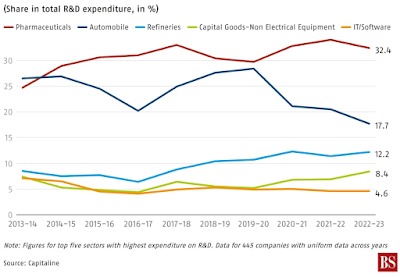

Business Standard reports that the R&D expenditures of Indian companies has been declining as a share of their net sales. It examined 445 S&P BSE 500 companies who spent Rs 651.3 trillion in the last decade of which less than one percent went into R&D.

Even this limited R&D expenditure has been skewed towards recurring costs (salaries, wages and maintenance).Companies in the United States spent the most on R&D (investing 8.1 per cent as a proportion of their net sales) in 2022. Chinese companies were the second biggest spenders (3.8 per cent) and the Japanese (3.8 per cent) came third. It was 1.7 per cent for Indian companies, according to data from the Economics of Industrial Research and Innovation.

No comments:

Post a Comment