FT has an excellent long read in the context of Bangladesh that highlights several policy challenges with the implementation of industrial policy and the green energy transition.

When Sheikh Hasina came to power in 2009 in Bangladesh, the country was suffering from electricity blackouts. She responded with policies that encouraged new fossil fuel plants like generous capacity payments and protection from legal challenges and prosecution, and eased imports of LNG.

Electricity generation capacity soared from 5.5GW in 2009 to 23GW currently, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a think-tank. As a result, Bangladesh’s entire population of 170mn now has access to electricity, compared with less than half in 2009. Prioritising gas helped limit the country’s dependence on coal. While coal imports have also grown, it accounts for 12 per cent of the country’s generation capacity compared to 50 per cent for gas, according to the BloombergNEF, a commodity research service. In 2021, Sheikh Hasina cancelled plans to build 10 new coal-fired power plants.

However, the reliance on imported natural gas and capacity expansion has now created a set of problems. On the one hand, is the problem of high gas prices and large capacity addition,

Yet Bangladesh now faces problems of a different nature. Electricity demand did not keep up with the building frenzy, and total capacity now exceeds demand by as much as 50 per cent. The lack of investment in new domestic hydrocarbon exploration also means the country’s domestic gas reserves are running low. That has left it at the mercy of global LNG prices. Unlike piped gas, LNG can be transported anywhere there are regasification facilities and cargoes tend to gravitate to the markets where prices are highest. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, that market was Europe — prices rose so high that traders were willing to pay penalty clauses to Asian countries in return for diverting their cargoes westward. Fuel shortages and a surging energy import bill pushed Bangladesh into one of its worst crises in years, with rolling blackouts and painful inflation. Foreign currency reserves have fallen about 20 per cent this year, according to rating agency Fitch, and the country has taken out a multibillion-dollar IMF loan to steady its economy.

On the other hand, there’s the issue of generous fiscal commitments made by the government to incentivize these investments

This means that even as Bangladesh struggles to afford fuel, more money goes towards capacity payments for projects that have in some cases been idle for more than a year. Bangladesh’s power sector subsidy burden jumped to Tk297bn (about $2.7bn) in 2022, the IEEFA said, 150 percent higher than a year earlier. The Summit Group has been a leading beneficiary of Bangladesh’s energy policies. Along with its upcoming plant in Meghnaghat, it is building several new LNG projects in addition to about 15 existing power plants. Of the Tk1tn ($9bn) of capacity payments by Sheikh Hasina’s government since it came to power, Summit has in recent years been the largest private beneficiary. Muhammed Aziz Khan, Summit’s founder, argues that Bangladesh has no choice but to import more LNG if it wants to avoid burning coal… to critics, the continued gas buildout shows that the interests of these powerful and politically connected conglomerates have long since overtaken considerations about energy security.

Rashed al Mahmud Titumir, an economist at the University of Dhaka, summarises the problem

Overcapacity, high retail prices, fuel shortages and now a struggle to pay energy bills — while subsidising an oligarchic clientele.

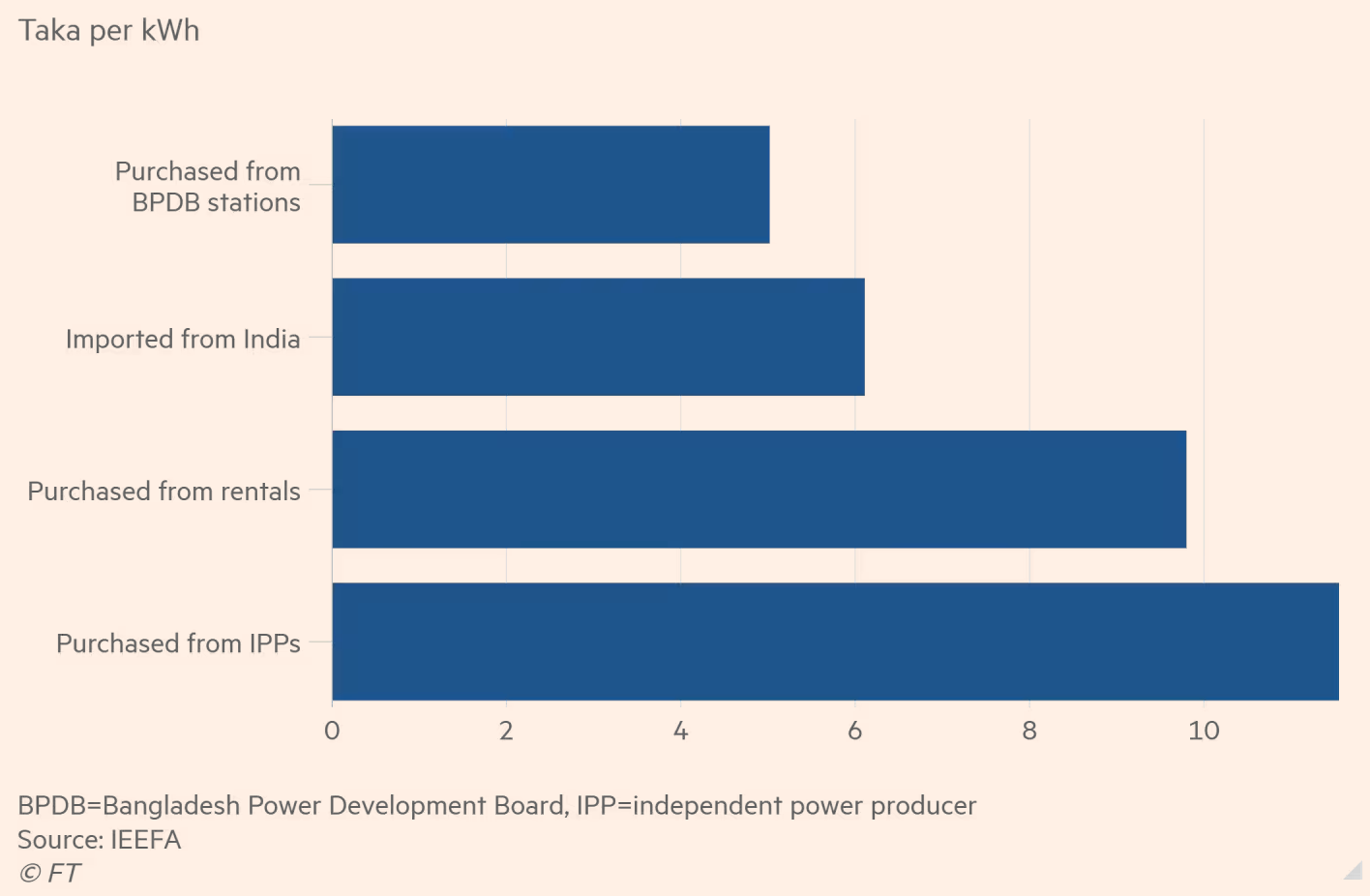

The private plants generate power at about Tk10 per kilowatt hour, roughly double the cost of that generated by state-owned companies.

The obvious option of renewable generation faces several problems

Analysts say land is in short supply in the densely populated country, while financial incentives continue to make fossil fuel projects more attractive to the private sector, resulting in a shortage of funding for renewables… Laurent Ruseckas, executive director for gas at S&P Global Commodities says that the lack of local supply chains for the construction of renewable capacity means that it’s not “seen as plausible to skip gas” in countries like Bangladesh. “You still need gas in those markets. The challenge for those countries is how to fit it into the energy system and make prices work.”

No comments:

Post a Comment