The ongoing debate in Japan over a foreign corporate takeover attempt makes for a good case study on capitalism.

The Canadian convenience store giant Alimentation Couche-Tard, best known for its Circle K brand, had made an unsolicited offer to Seven & i Holdings the owner of Japan’s iconic and much-loved konbini stores chain 7-Eleven. It emerged late last week that the Board of Seven & i Holdings rejected the $39 bn cash takeover offer for being “grossly undervalued”.

Western commentators and investors have long held that Japanese companies suffer from corporate governance failures, allocate capital inefficiently, and are generally run inefficiently. They want Japanese companies to embrace the shareholder value maximisation approach that dominates the Western corporate world. They blame Japan’s long period of economic stagnation on the failings of the country’s corporate management culture.

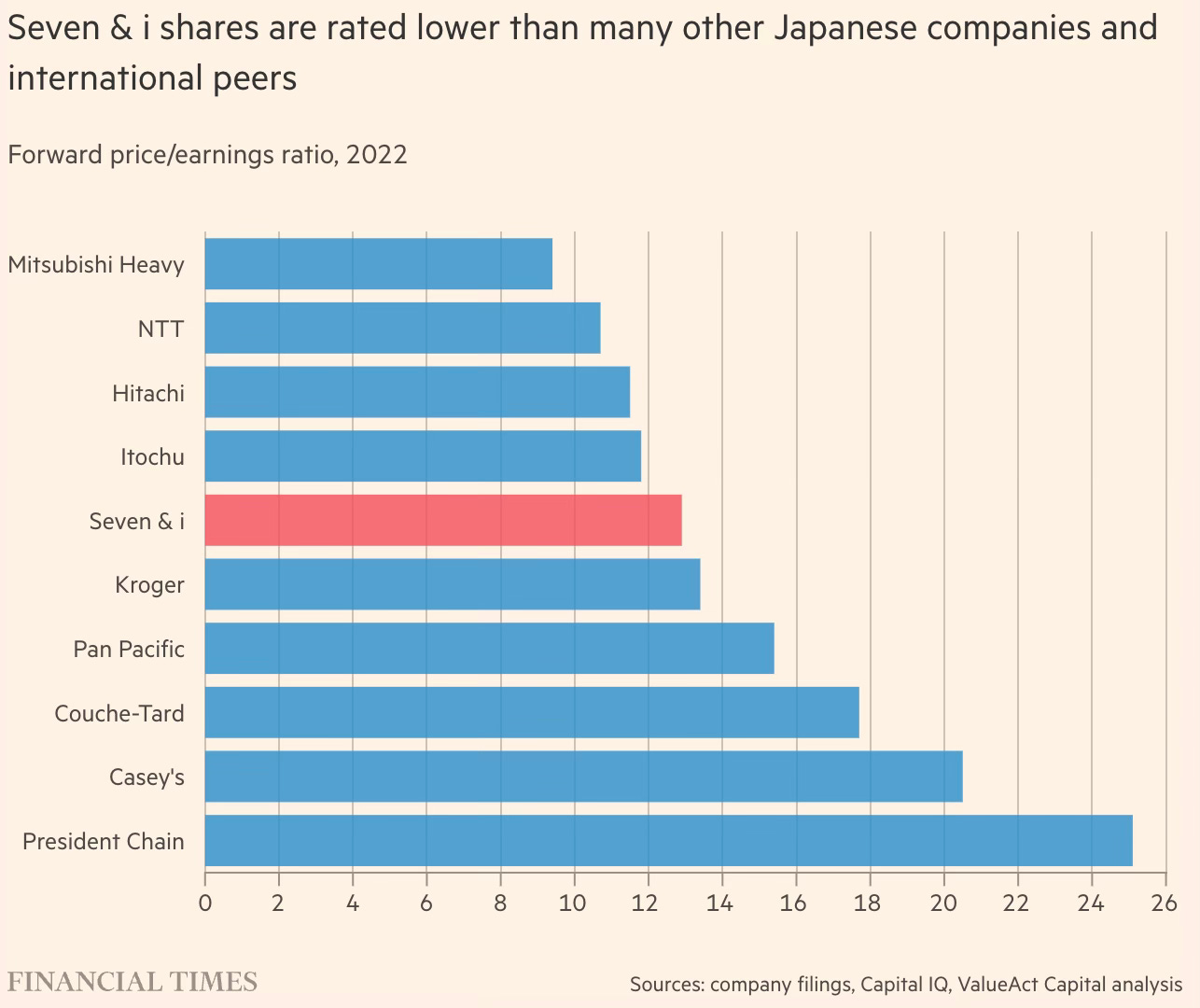

They point to the generally depressed valuations of Japanese companies and argue that there’s considerable value to be unlocked by Western-style corporate governance reforms. Such reforms involve prioritisation of operational efficiency and profit maximisation over other concerns and relationships involving labour, customers, and communities.

There are two contrasting corporate philosophies at work here - the Western shareholder value maximisation one and one where the objective is to maximise the stakeholders’ value.

The US and Japan are totemic examples of each version, and both have their share of corporate governance and other failings. In the US, the excesses of shareholder value maximisation have shortchanged customers and societies and corporate governance failures are manifest in executive-level aggrandisement. In Japan, the deficient focus on efficiency and diversification over unrelated activities and businesses lower shareholder value, and opacity-increasing cross-holdings (the conglomerate discount) weaken corporate governance standards. In other words, both approaches suffer from their respective shares of inefficiencies. In the general equilibrium, the adverse consequences of Japanese corporate management is no worse than that of US corporate management.

This is a good summary of why the konbinis are so prized in Japan

Convenience stores or konbini are the pinnacle of what Japan does best. They sell fresh bento, reasonably priced Cabernet Sauvignon, gelato, shirts, funeral offerings, cosmetics, metal dinosaur kits and concert tickets. Customers can pay their tax bills there, or do their banking. They have strived to become indispensable and won. Behind the scenes, the operation is powered by automation, robots, finely tuned supply chains and efficient distribution logistics… konbini have evolved into Japan’s most powerful conduit of consumption, temptation and retail innovation. After years of consolidation, the country now has three significant competitors: 7-Eleven, Family Mart and Lawson, who together control more than 50,000 stores in their home market. Almost half of those are run by Seven & i, and pull in 22mn customers a day.

These two testimonials from two consumers sums it all

“I think foreigners should be able to buy Japanese companies,” says the customer buying cat treats. “But I do not believe a foreigner could run this particular company.”…“I probably spend more money in 7-Eleven than in any other shop, they are just always there, they are part of life and the food has kept getting better,” says the coffee-and-croissant purchaser. “I heard they might be sold, but I don’t think that can happen, can it?”

The conclusion of the article has an excellent summary of the two competing corporate philosophies.

The primacy of shareholder value, largely unquestioned in other large developed markets, is still very much up for debate in Japan. Ogawa, at Nippon Active Value Fund, describes it as “the eternal question: for whom is a Japanese company run?”There appears little doubt about the bidder’s views on the matter. Couche-Tard is “the thing that was always missing”, according to the veteran investor. “Someone to step up and accept the risk of becoming known as a horrible person, an aggressive bidder prepared to take a reputational hit in Japan. But Couche-Tard hasn’t got anything else it will ever want in Japan, so what has it got to lose?”Travis Lundy, an independent special situations analyst who publishes on the Smartkarma platform, says the Canadian group “is very aggressive and religious about costs, while Seven & i is religious about customer experience, offering multiple kinds of delicious onigiri, freshly made sandwiches, fluffy bread, yoghurts, the lot”. For many Japanese, that is what the takeover battle could ultimately boil down to. “If Couche-Tard’s goal is to increase margins,” says Ogawa, “it’s hard to figure out how that can happen without a degradation of customer experience.”

This is a very good case study. A retail chain like 7-Eleven can legitimately be thought to target three objectives - serve its customers well, run its operations efficiently, and in the process generate good returns for its investors. 7-Eleven stands alone at the top in the first, does part of the second great (the 7-Eleven part) but not so the other part (its corporate holdings and capital allocation), and struggles badly in the third. In contrast, western retailers tend to prioritise efficiency and financial returns over customer service.

The outcomes of these two models too are different. The US version has created a system where the equity markets and the top executives are in charge (in the private equity model, it’s the fund managers in charge). This creates perverse incentives that distort the principal-agent relationship between shareholders/investors and executives/managers. It manifests in grossly excessive executive compensation, low job security and worker morale, aggressive cost minimisation, lower customer service standards, forms of asset stripping, prioritisation of short-term considerations, and so on. All these are invariably aimed at boosting the bottom line and valuations, and aggrandising executives/managers.

Instead, the Japanese version of capitalism has avoided or limited these undesirable practices and trends (though it has its set of returns lowering inefficiencies and poor capital allocation). Its focus on product quality and customer service, managerial accountability, corporate pay structures, concern for employees, technology adoption, and so on are admirable. This Japanese version of capitalism is a reflection of its cultural and social norms.

The Japanese caution in the acceptance of American-style capitalism is therefore understandable and desirable. Instead of framing the problem as that of adoption of US-style corporate practices, its challenge should be about addressing its corporate structure inefficiencies and generally improving corporate governance, while retaining the several good features it currently possesses. In any case, it should not allow its capitalism to become disconnected from the values that underpin its culture and society, no matter what the returns.

1 comment:

Hi Mr. Natarajan, great case study.

What do you think is the reason behind Japanese conglomerates being unable to do both - exit their loss-making ventures and serve customers well at the same time?

While customer satisfaction and shareholder interest may be odds (especially in the retail business case here), I'm not sure how this conflict forces companies to subsidise their losing businesses at the expense of their winners.

Post a Comment