A widely held misconception about infrastructure finance is the belief that bonds are a major source of infrastructure debt finance. In reality, even in developed countries (excluding the US), banks are the overwhelmingly major source of debt mobilisation. Historically, bond markets have been small contributors even in Europe. I have blogged extensively on this.

In India this belief has led to several years of intense debates and policy making efforts at broadening and deepening bond markets. Influential opinion makers weigh in with theoretical arguments about why bond markets are critical to infrastructure financing and how our reliance on banks have been the bane of the banking sector. In sharp contrast, efforts to enable banks to overcome their asset-liability mismatches, lower their cost of financing infrastructure, and improve their quality of due-diligence of infrastructure projects have received disproportionately less attention.

This post will point to an important regulatory constraint arising from Basel III framework that raises the cost of capital for bank financing of infrastructure.

Before we get to the main point, let me point to a few more illustrations of the marginal role of bonds in infrastructure finance.

Bonds have been a very small proportion of all lending specifically to infrastructure projects.

In 2022, fresh private investment by way of equity and debt in greenfield and brownfield projects globally was around $350 bn, of which bank loans made up 72% of the debt mobilised and bonds made up just 19%. The share of bonds would have been even lower but for green bonds.

As mentioned earlier, despite this reality, a disproportionate amount of policy effort in India and elsewhere goes into bond market reform. It's in this context that there should be more policy efforts at making it easier for banks to lend for infrastructure projects. Such reforms should try to reduce the cost of funds for banks and address the critical issue of asset-liability mismatch that banks face from lending long-term.

First, there will be a tightening of the large exposure rule, i.e., how much a bank can be exposed to a given borrower or project. Given that infrastructure projects are typically large, this might prevent lending especially by smaller banks. Second, under Basel III, there is a tightening of capital requirements for infrastructure projects which makes lending for such projects costlier. A third constraint comes through liquidity requirements, newly introduced under Basel III, under the so-called net stable funding ratio (NSFR) and liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). These requirements will force banks to (i) match longer-term lending (such as for infrastructure) with longer-term funding, which, of course, implies that banks have access to this type of funding, and (ii) hold more cash-like assets for project funds. Both requirements are more difficult to fulfill for banks in many EMDEs. Finally, there might be reluctance to commit to longer-term funding structure given the increased uncertainty over further regulatory tightening. Since the 2008 crisis, there have been frequent changes to regulatory standards, ranging from Basel II.5 to Basel III to recent additional reforms to Basel III (sometimes referred to as Basel IV) and discussion on another round in a few years (sometimes referred to as Basel IV or V).

Cross-border syndicated loans to developing countries — often used as a way to get foreign bankers into projects in emerging economies — fell as a proportion of the total from almost 90% in the 2000s to just over half by 2014. New ways of weighting the risk attached to various assets — such as those the Basel III endgame proposes to implement for US banks — threaten to penalize the poorest countries the most. One study by the G-20’s Global Infrastructure Hub found that if banks used actual historical data instead of the new mechanisms, it might make a 37% difference in how they evaluated their possible losses from loans to infrastructure in developing countries, but only 11% in loans to high-income ones... In the 2000s, banks could lend to infrastructure abroad at margins of 50 basis points; that rose by 2016 to 250 to 300 basis points. When you add this much friction, bankers stop looking for the best projects, only the safest ones — and lazy banking means that savers earn less... Policymakers should consider how endless restrictions aimed at preventing a future financial crisis are worsening a climate crisis that threatens devastating impacts now.

The Base III endgame, or the last round of the Basel III reforms finalised in December 2017 and now getting implemented, involves the following:

A key objective of the revisions … is to reduce excessive variability of risk-weighted assets (RWAs) … [and] help restore credibility in the calculation of RWAs by: (i) enhancing the robustness and risk sensitivity of the standardised approaches for credit risk and operational risk, which will facilitate the comparability of banks’ capital ratios; (ii) constraining the use of internally-modelled approaches; and (iii) complementing the risk-weighted capital ratio with a finalised leverage ratio and a revised and robust capital floor.

The study by the Global Infrastructure Hub referenced in the Bloomberg article writes about how Basel III norms raise capital costs for infrastructure borrowers.

As banking regulations are not explicitly defined for the infrastructure asset class, they impose higher capital charges and equity investment than appropriate. These higher financing costs either translate into higher prices for infrastructure services (straining consumer affordability), or higher government support (impacting the already record-high global government debt levels)... The lack of recognition in the Basel Framework of infrastructure as an asset class or its subset means that the regulatory rules applied on infrastructure loans are not attuned to its risk sensitivities. The risk weights used for infrastructure loans are typically based on the credit profile of the issuing entity (government, multilateral development banks (MDBs), or corporates). This is problematic mainly for infrastructure loans given to project finance entities which are newly created for a given infrastructure project and have no credit history. The project finance route is taken so public and private sectors can work together for infrastructure development. Current risk weights applied on project finance loans are much higher than those seen in historical risk profiles of infrastructure projects. A GI Hub data assessment finds there is scope to reduce regulatory capital charges by 60% if historical data are used to define risk weights for the infrastructure asset class.

The GI Hub study also writes about the incentive problem with the IRB approach.

Ensuring internal ratings based (IRB) outputs are not less than 75% of those from the standardised model, the output floor was introduced for consistency between the different approaches used by banks. Prior to the introduction of the output floor, the lack of treatment of infrastructure as an asset class was not a major problem. Through the IRB route, banks could use actual risk values observed in the historical performance of infrastructure loans. While banks can still use IRB models, the output floor reduces the incentive to do so. As infrastructure projects do not constitute a large share in their total asset portfolios, banks may not adopt the IRB approach just for the infrastructure asset class. Under the standardised approach, it will be more costly for banks to finance infrastructure projects due to high capital charges.

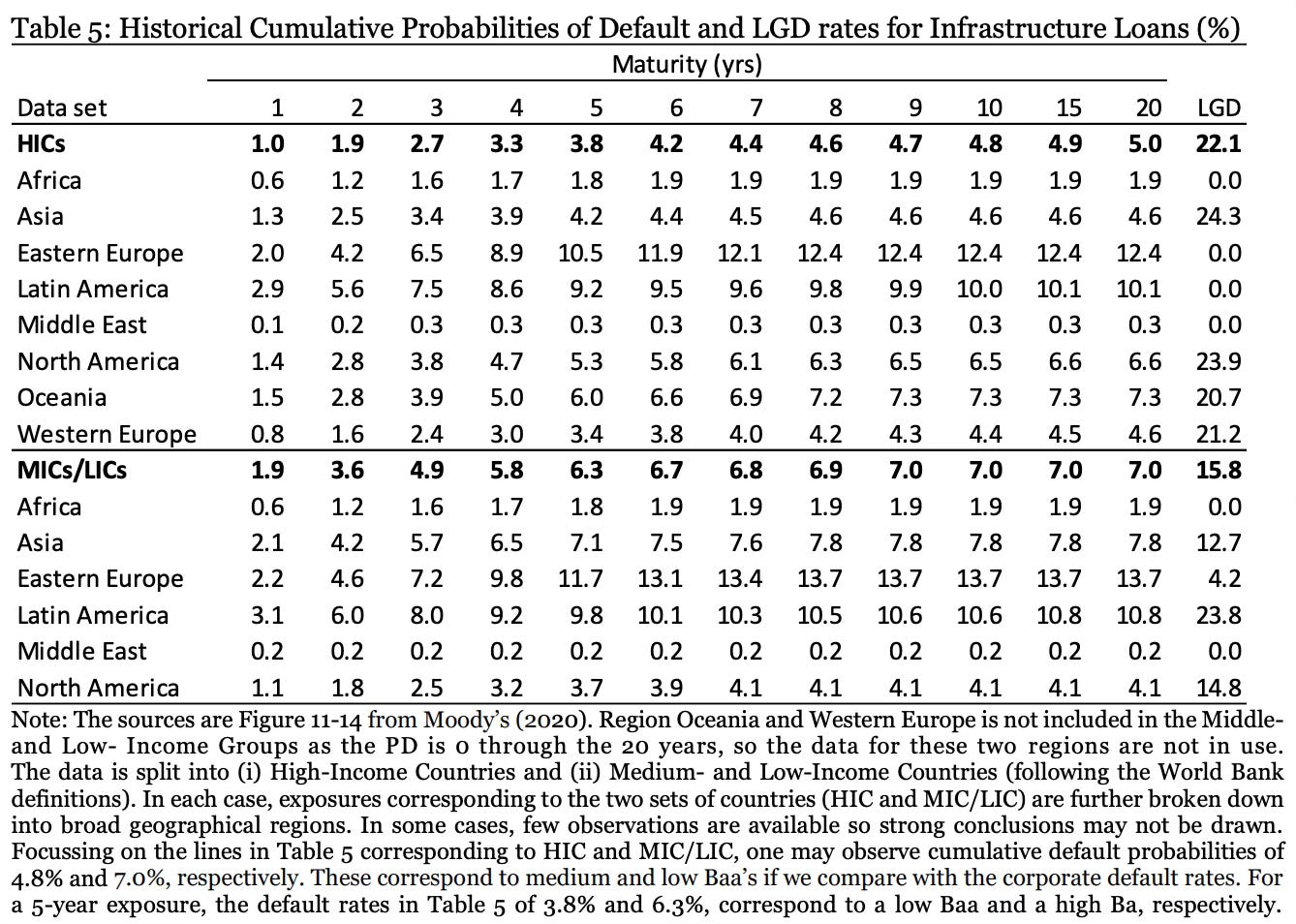

It finds that use of actual historical data instead of Basel III standards would lower loss estimations from infrastructure by 37% for middle and low-income countries.

For the IRB approach, the Basel Framework has defined Loss Given Default (LGD) input floor by asset class. As regulatory rules are not specifically defined for the infrastructure asset class, the default LGD input floor of 25% for unsecured lending applies. Historical data shows that average LGD values for the infrastructure asset class are highly attractive at less than half that for non-financial corporates. The estimated capital charges based on historical LGD data from actual infrastructure projects are lower than the charges implied by the 25% LGD input floor.

A comparison of the actual infrastructure project defaults covering 7047 project loans originated from 1983 to 2018 across several sectors reveals interesting insights. There were 19 defaults in 1006 social projects, 97 defaults in 1114 transportation projects, 18 in 305 water and waste projects, 46 in 395 media and telecom projects, 17 in 278 oil and gas distribution projects, and 240 in 3881 power generation and transmission projects. It had 335 defaults in 5909 projects in high income countries and 107 in 1138 projects in low income countries.

The right-hand column of Table 5 shows Loss Given Default (LGD) estimates for defaulted infrastructure loans. The figures for the broad categories of HIC and MIC/LIC are 22.1% and 15.8%. These LGDs (of approximately a fifth and a sixth) are extremely low compared to corporate bonds for which LGDs of 50% are more standard. Corporate loans are often presumed to have LGDs of around 45-40%. LGDs of half or a third of those for say senior unsecured bonds mean that the expected losses on infrastructure loans are comparable to relatively highly rated corporate debt securities. To illustrate, a 10-year unrated, HIC infrastructure loan has an Expected Loss equal to 4.8% x 22.1%, i.e., approximately 1%. Assuming a 50% LGD as is common for a senior unsecured bond, this represents the same EL as a 10-year A-rated bond (which, from Table 4, has a default rate of 2.1%).

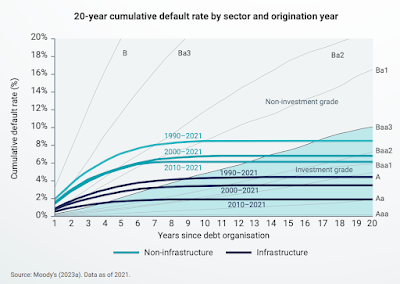

The GI Hub’s Infrastructure Monitor Report 2023 has a graphic which shows that with lower default and higher recovery rates, the average expected loss on infrastructure loans are only a fourth of that for non-infrastructure loans in both high-income and middle- to low-income countries.

Default rates on infrastructure loans are lower than that for non-infrastructure sector and have been decreasing over time across all infrastructure sectors.

The GI Hub report draws from research which is cited in this note by Allianz Research. As pointed out above, infrastructure projects have a much lower default probability than corporate loans over the long term.

The research note’s conclusion is encouraging

Our findings based on new data from Moody’s Investor Services and Standard and Poor’s (Jobst, 2018a) suggest sufficient scope for lower capital charges to be applied to infrastructure investment—through project loans—without altering the current (or planned) calibration methods. While the initial default rate exceeds the level for investment-grade corporates, it steadily declines as the loans mature. After about five years, the marginal default rate is consistent with solid investment-grade credit quality, creating a distinctive “hump-shaped” risk profile (Figures 6 and 7). The recovery rate is high, comparable to that of senior secured corporate loans. This favorable credit performance is even more pronounced for projects in sectors that would fall within the scope of the eligibility requirements for green bonds (Jobst, 2018b). In fact, on a global basis, green infrastructure projects seem to default only half as often over a 10-year period as “brown” projects, with a greater difference in emerging markets relative to advanced economies. Capital charges that recognize the declining downgrade risk of infrastructure debt over time could potentially free up capital; this would help mobilize resources to finance infrastructure—thus promoting the green transition.

The study points to other ways in which Basel III discourages infrastructure lending by banks.

In the Basel Framework, the benefits of credit-risk mitigation instruments can be availed if the legal language of unconditional, continuous, and irrevocability is met. Project finance contracts are not straightforward and have legal obligations defined for all parties for different categories of performance outcomes and risk categories. Such contractual complexity curtails the benefits of credit-risk mitigation instruments (i.e. lower capital charges and better terms of finance) for infrastructure project finance loans... the complexity of project finance contracts makes ratings difficult and expensive to obtain - despite the Basel Framework’s high reliance on them. Additionally, many rating agencies do not follow a recovery-based approach, which should be used to rate infrastructure projects given their superior recovery rates over most other asset classes.

It’s clear that given the predominance of bank loans in infrastructure financing, it’s important to examine the problems associated with bank lending to infrastructure projects and remove the bottlenecks and make it easy to undertake such lending. In this context, here are some thoughts on infrastructure financing through banks.

1. For a start, the GIHub article itself refers to changes by way of lower regulatory capital requirements for infrastructure in Europe, South Africa, and China.

The International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) - the international standards-setting body for the insurance sector - conducted an extensive definition and data review for infrastructure investments and is reforming the Insurance Capital Standard to introduce risk-sensitive regulations for the infrastructure asset class. In Europe, the Solvency II regulations were amended in 2016 to lower capital charges for ‘Qualifying Infrastructure Investments’, and the same followed in South Africa. China’s Risk-Oriented Solvency System (C-ROSS) also has distinct capital charges for infrastructure exposures. The European Banking Authority (EBA) introduced ‘Infrastructure Supporting Factor (ISF)’ to provide a 20% regulatory capital discount to eligible infrastructure investments. EBA found that the market adoption of ISF was lower than expected.

I confess to not having researched India’s own regulatory treatment of infrastructure. But assuming that it has not made any significant changes to the Basel III framework, India would do well to examine and develop its own appropriate regulatory capital requirements instead of adopting Basel III endgame in full. This is most essential given its direct role in the determination of cost of capital for infrastructure project loans.

The Government could collect historical data on infrastructure loans from banks and analyse them for actual default related parameters across sectors and banks. It should then be compared with the regulatory capital requirements prescribed for banks to decide on the nature of changes required to be made to the existing regulations.

2. India should also engage at the Basel Committee on Banking Regulation to revisit the regulatory requirements under Basel III for infrastructure, especially in light of the prioritisation of efforts to attract private capital from developed countries to finance climate change adaptation and mitigation projects. This is important to increase lending by foreign banks to developing countries which has fallen alarmingly since early 2000s.

3. In an earlier post in the context of sovereign credit ratings, I had suggested that Government of India should support the development of a data repository on ratings and few other parameters. On the same lines (and similar to the Moody’s Analytics Data Alliance Project Finance Consortium), the GoI should make a data depository that tracks all infrastructure projects, their financing structures, and their life-cycle outcomes. This would require engagement with all financial institutions and a mechanism to facilitate contiuous sharing of information. This has to be a project in itself and cannot be done by a Department within the government. One option is to mandate NIIF to do this as part of its infrastructure market development role. This database can serve as invaluable decision support for several important decisions on policy making as well as financial structuring of individual projects.

4. Infrastructure financing combines two distinct and qualitatively different kinds of risks - construction and operations. As shown above, the life-cycle risk profile of an infrastructure project is hump shaped, with the initial construction risks being high often rising further, only to decline sharply and stabilise at very low levels during the operations phase. This deters private capital from investing in greenfield projects which invariably have construction risks. It's essential to acknowledge this while structuring infrastructure financing. Accordingly, bank loans should be structured to finance construction and O&M as distinct activities with different pricing and terms. It’s required to examine the banking regulations in this regard and remove bottlenecks that deter such structuring.

5. Finally, banks grapple with the problem of asset-liability mismatches when lending to infrastructure projects. It’s required to actively engage with policy facilitation that address this problem. One way is the aforementioned changes to the Basel III norms to recognise infrastructure as a distinct asset category with its long-term and illiquid nature. Another way to ease this is to make it easier for banks to raise resources by issuing long-term bonds and then using it to make loans to projects. A third option is to make it easier for banks to securitise infrastructure loans and free up their balance sheets. This would require policies that encourage and facilitate demand for securitised infrastructure debt assets. A fourth option is to make it easier for banks to come together and provide syndicated loans. Syndication arrangements like takeout financing should be incentivised.

No comments:

Post a Comment