This blog will look at the data on the trends associated with credit allocation and their sources in India how it compares with other major economies. The data is sourced mainly from BIS.

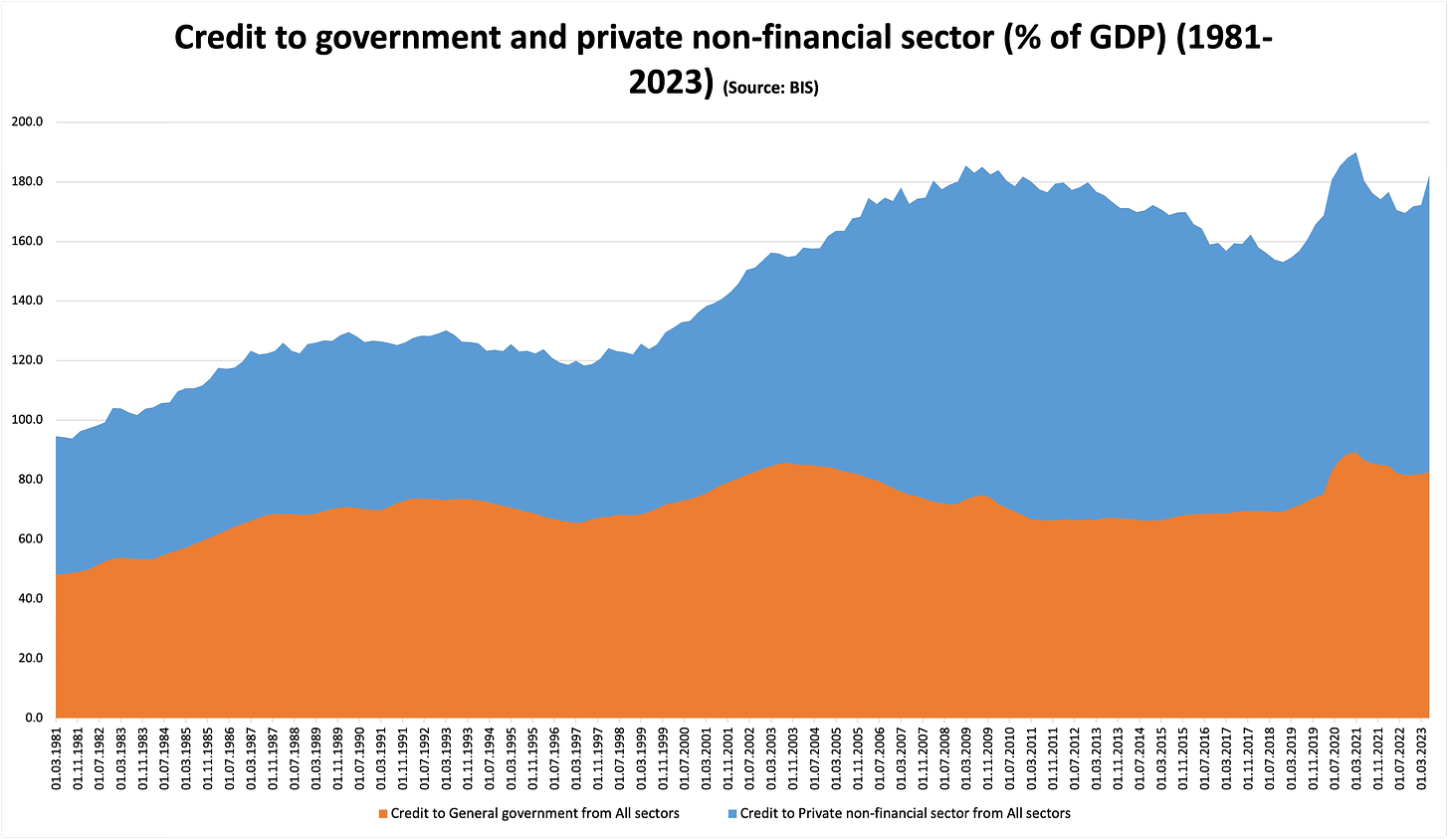

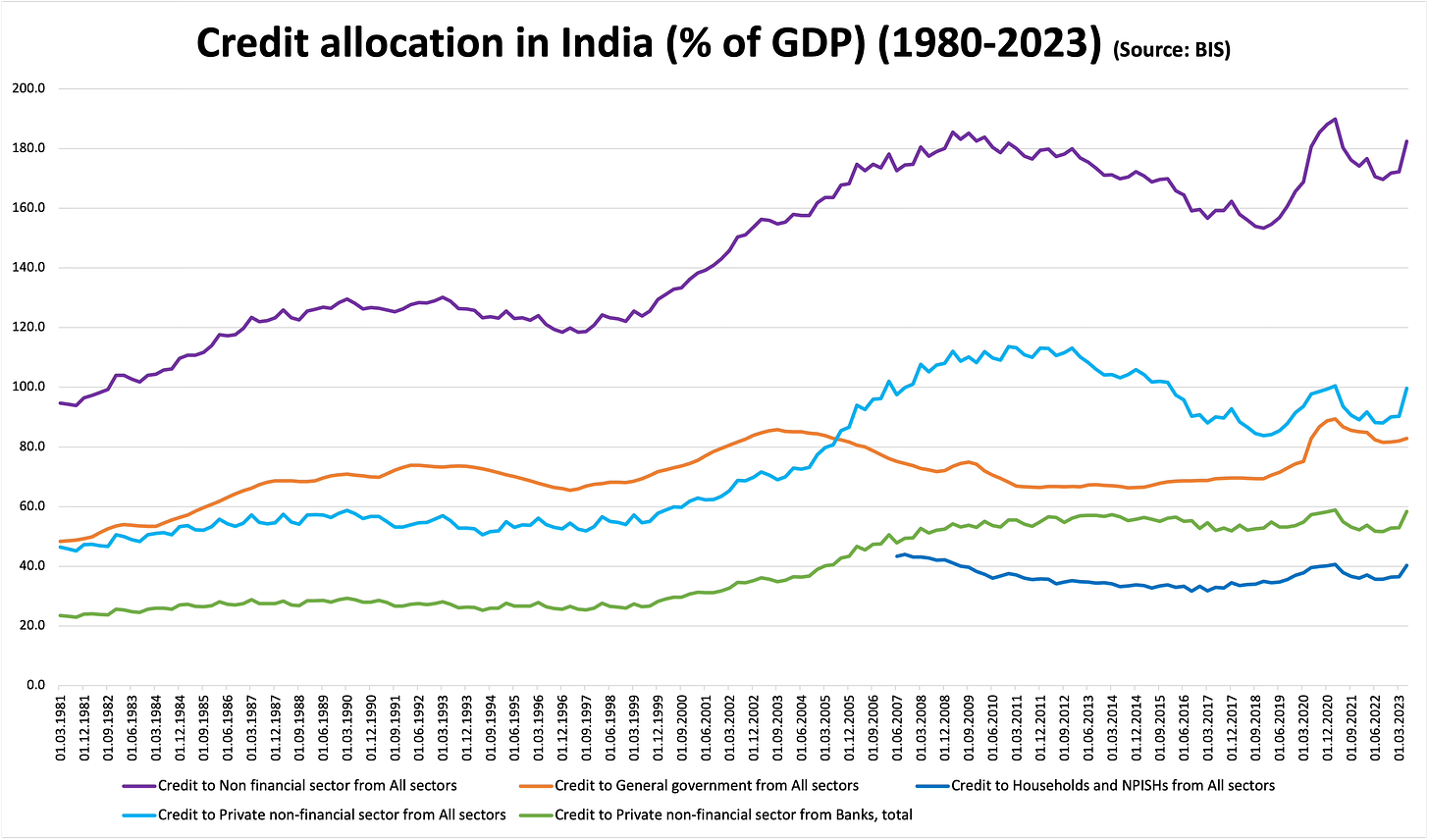

After rising slowly since 1980, credit to government as a share of GDP declined since about 2003 and has been at a stable 65-70% from 2010-18. But it started climbing before the pandemic and rose sharply during the pandemic to 89% of GDP in Q1 2021. While credit to private non-financial sector too followed the same trend, there was divergence since early 2000s when it started to rise sharply to peak by the rime of the global financial crisis. It then declined, only to rise again since 2019. The increased share of credit to private non-financial sector coincides with the increased role of non-bank institutions like capital markets, non-banking finance corporations (NBFCs), external commercial borrowings, private debt etc in raising debt.

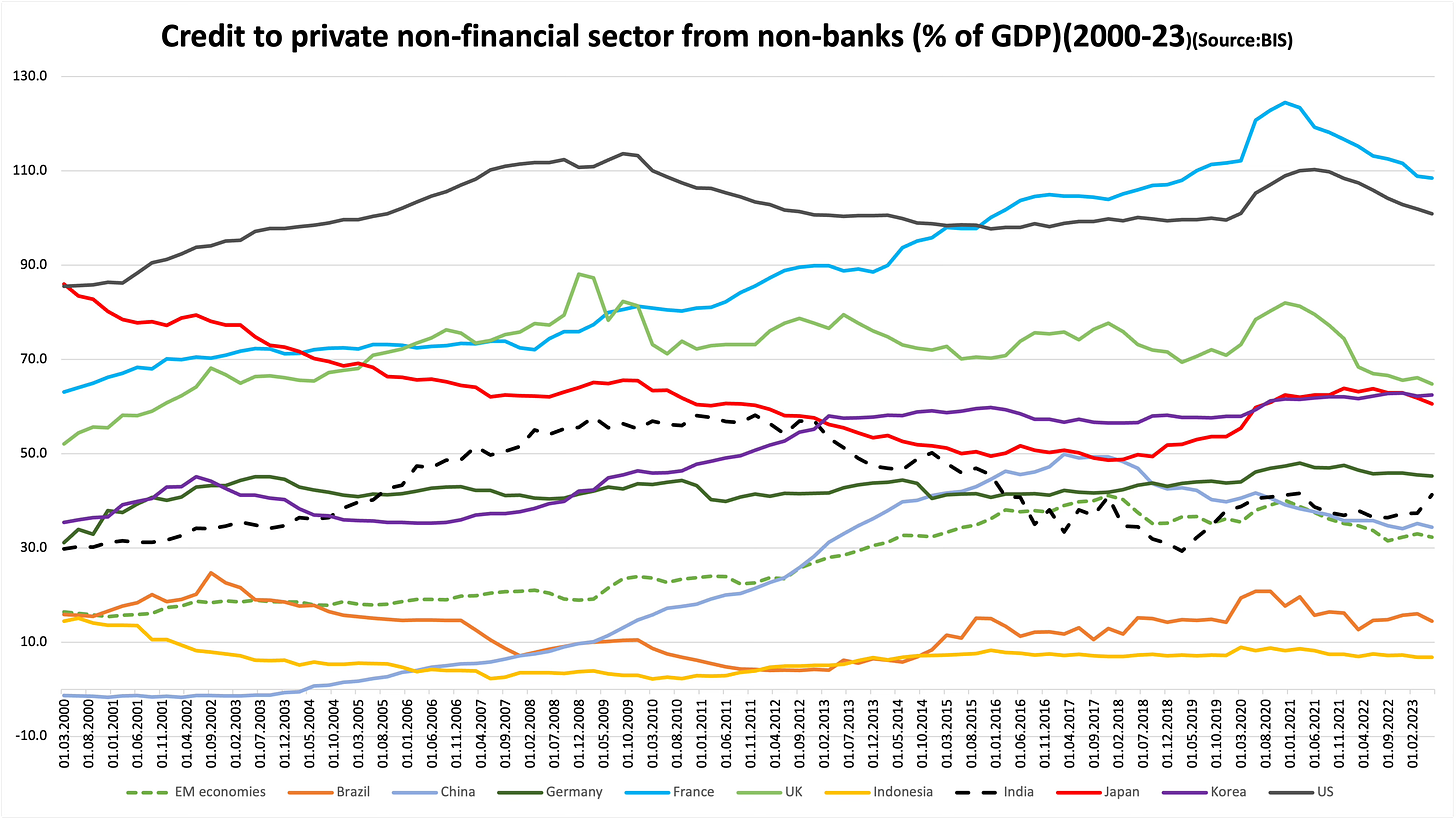

But there was surge in credit from non-bank institutions (bonds, shadow banks, ECBs, private debt etc) to private non-financial sectors from the beginning of the millennium. However, it peaked by 2012-13 and has since declined and stabilised. This trend is in line with the increased use of capital markets and NBFCs in India to raise debt.

Bank credit has mirrored the trends in private non-financial sector credit as a whole. While it has nearly doubled to about 55% of GDP over the last two decades, it appears to have plateaued since 2008 in the 50-60% range.

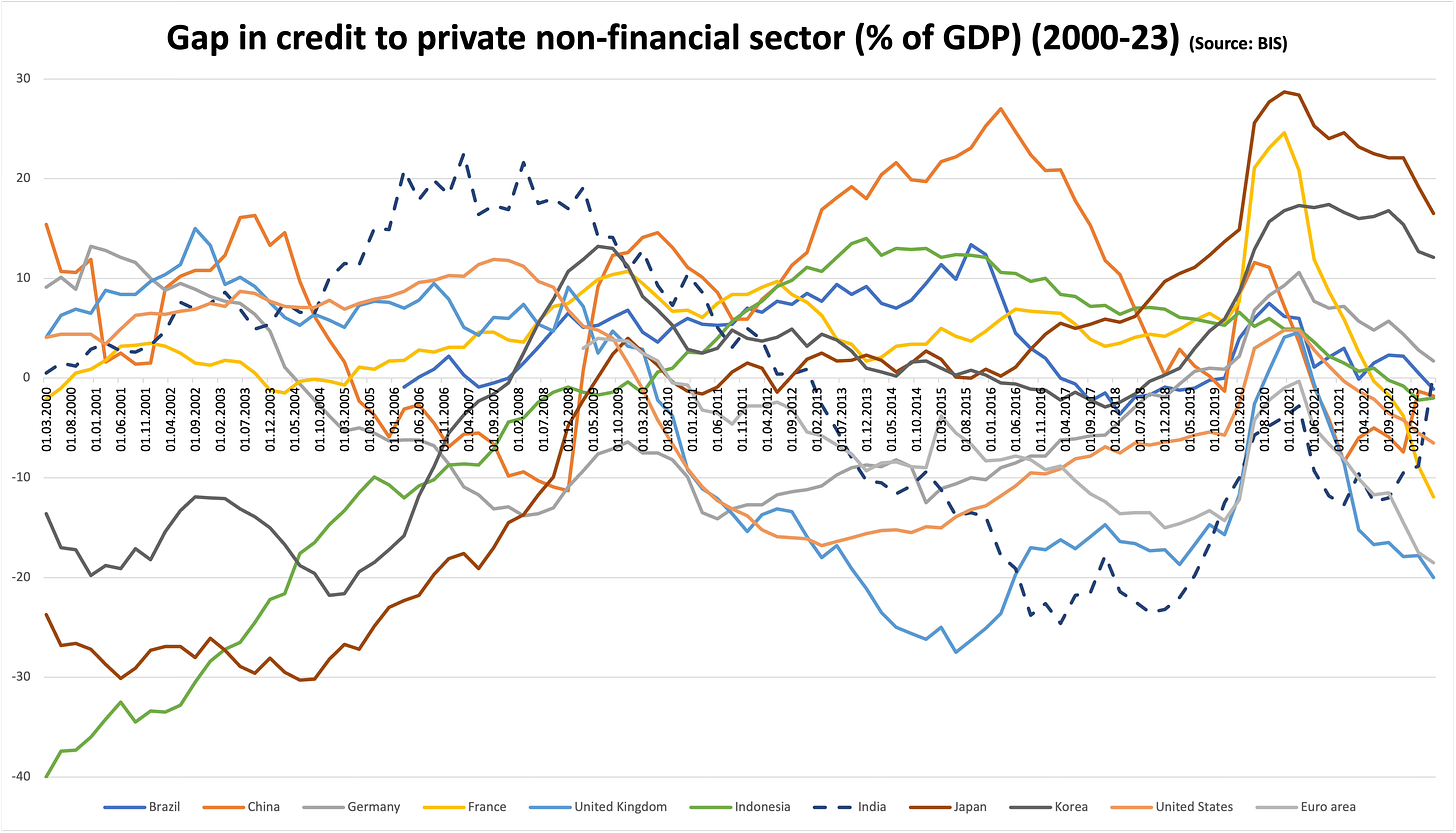

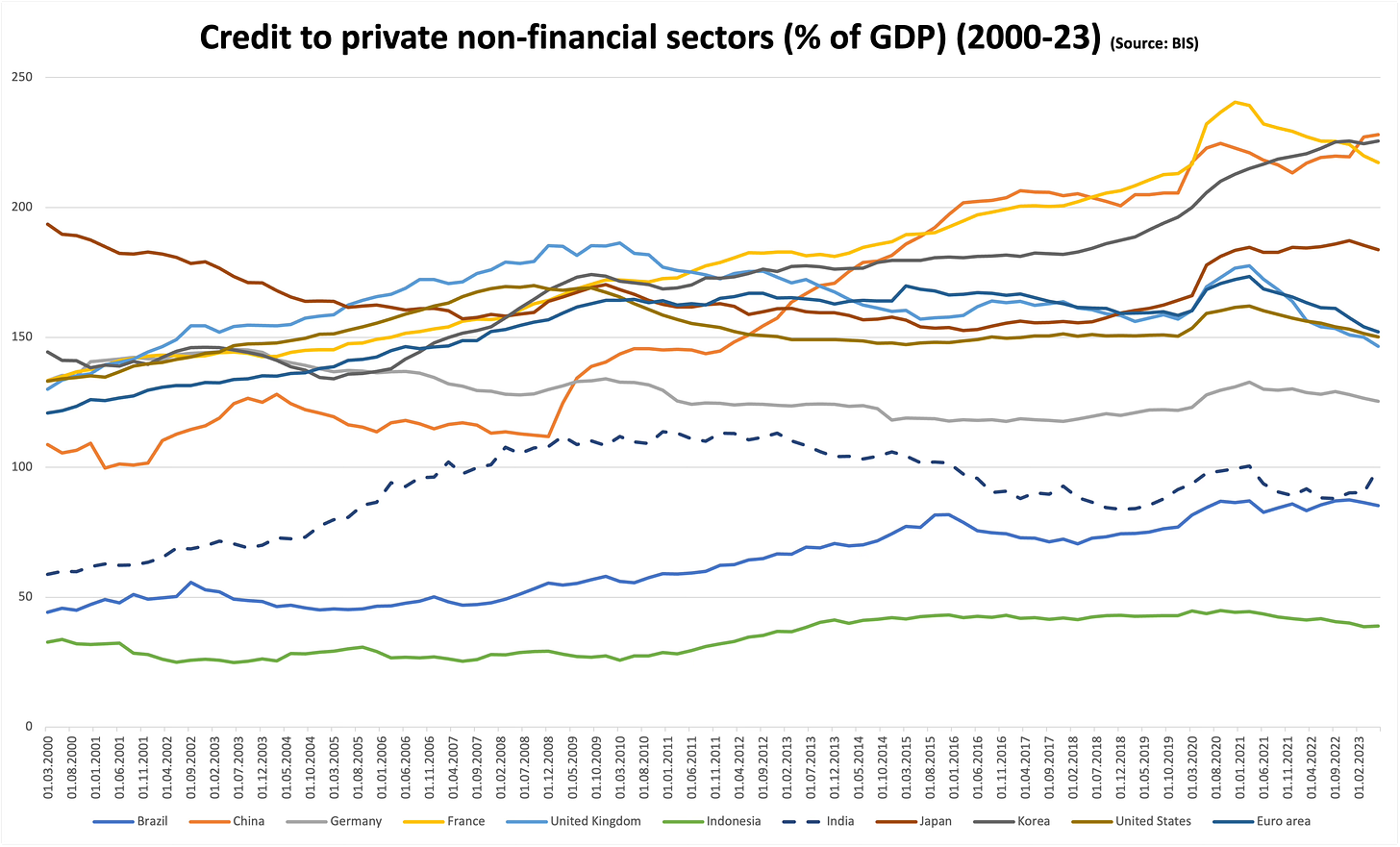

Credit to private non-financial sectors has been on a declining or stagnating trend as a share of GDP in India since the global financial crisis compared to other countries.

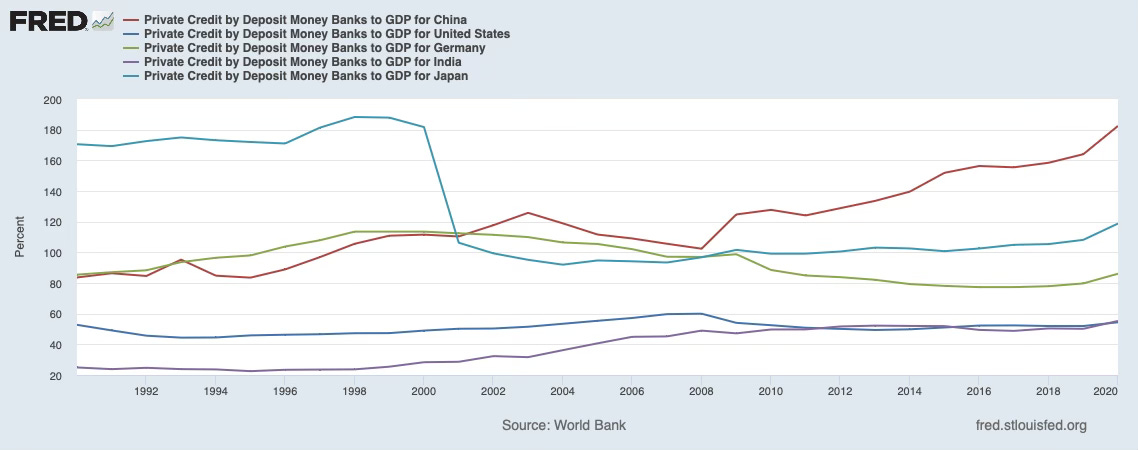

Despite all the hype around the rise of fintech and the talk of decline of deposit taking banks, bank credit to the private sector continues to remain stable as a share of GDP. In India it has nearly doubled to about 55% of GDP over the last two decades, though it appears to have plateaued since 2010.

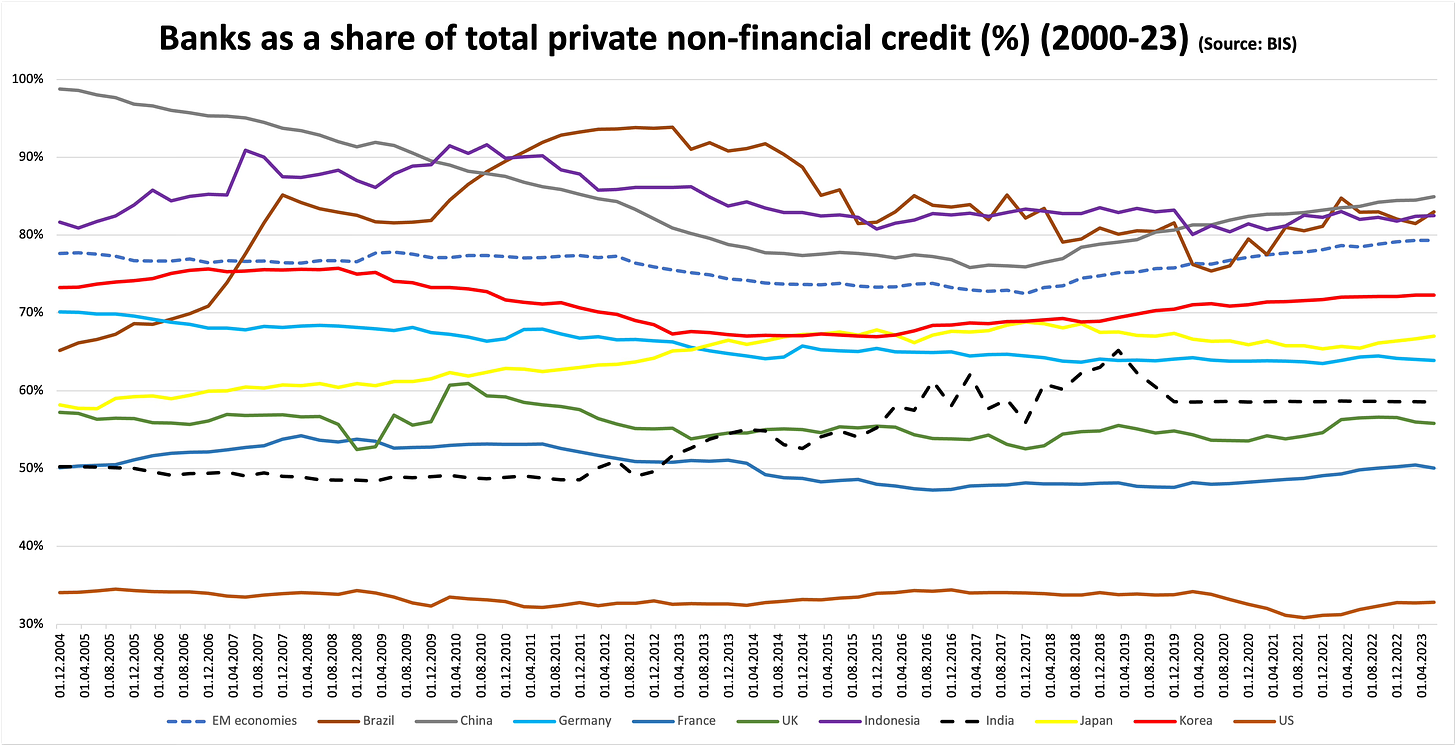

In fact, bank’s share of total private non-financial credit has remained stable across countries, developing and developed, despite the rise of alternative non-deposit taking bank credit institutions (bond markets, shadow banks, private credit etc). In India, its share has risen by about 10 percentage points since 2012 to make up slightly less than 60% of total private non-financial credit.

Credit from non-banks has sharply declined from a peak of 58.1% of GDP at the end of 2010 to 41.3% by end of H1 2023, briefly touching 31% by end of 2018. This runs counter to the widely believed story on the diversification of Indian economy’s credit allocation universe.

Unlike its developing country peers, India has been suffering a credit gap since the beginning of 2012.

|

Availability of affordable capital, equity and debt, is one of the biggest constraints to business formation and expansion in India. The graphics clearly indicate that India has a lot of catching up to do on the debt intermediation side. It’s reflected in the stagnation at low levels of credit to private non-financial sector and the prolonged credit gap for more than a decade. For all the hype about it displacing bank credit, the share of non-bank credit to private non-financial sector has been on a declining trend, even as the share of bank credit has been rising. In this context, notwithstanding the hype around bond markets, I had blogged here about the central role of banks in financing of infrastructure.

In this context, we should be careful not to be misled by misplaced enthusiasm about fintech and other financial innovations, and disdain for boring old-fashioned banking. For those who claim that the future of finance is going beyond banks, the graphs above show that bank lending to private non-financial sector is several multiples higher in developed countries than in India and also they have been on a rising trend. Further, credit to private non-financial sector from non-banks has been on a declining trend since about 2020. This trend is unlikely to change given the end of the era of ultra-low interest rates and return to normalcy in interest rates.

As I have blogged here and here, in the absence of access to financing resources, fintechs can at best be a means to help banks improve intermediation breadth, effectiveness and efficiency. Here too, given the struggles faced by fintech with big-data based credit scoring and limited headway with micro-credit/savings/insurance products there remain several questions. After all the iteration over the coming years, we are likely to converge to a universe where banks partner with fintechs on services like customer acquisition, credit scoring, and payment collections. The core areas of banking like mobilising capital, loan origination, and loan book management are likely to remain with banks. This way banking would have become more efficient and effective. But this is not the future of finance posited by many experts today.

No comments:

Post a Comment