There are several arguments put forth to explain Industrial Revolution. Why did IR take-off in Europe and not elsewhere, and more specifically in UK and not elsewhere in Europe itself? The more common arguments concern Britain’s commercial successes, its more advanced institutional developments, and its greater urbanisation compared to European peers.

John Burn-Murdoch points to Joel Mokyr’s argument that it was broader cultural change that made Britain the pioneer of IR. The Enlightenment thinking’s rationalism and empiricism, science and experimentation, and a progress-oriented view of the world are held as drivers behind this cultural transformation.

Burn-Murdoch points to a recent IZA working paper by Ali Almelhem, Murat Iyigun, Austin Kennedy, and Jared Rubin.

The researchers analysed the contents of 173,031 books printed in England between 1500 and 1900, tracking how the frequency of different terms changed over time, which they use as a proxy for the cultural themes of the day. They found a marked increase in the use of terms related to progress and innovation starting in the early 17th century. This supports the idea that “a cultural evolution in the attitudes towards the potential of science accounts in some part for the British industrial revolution and its economic take-off”.

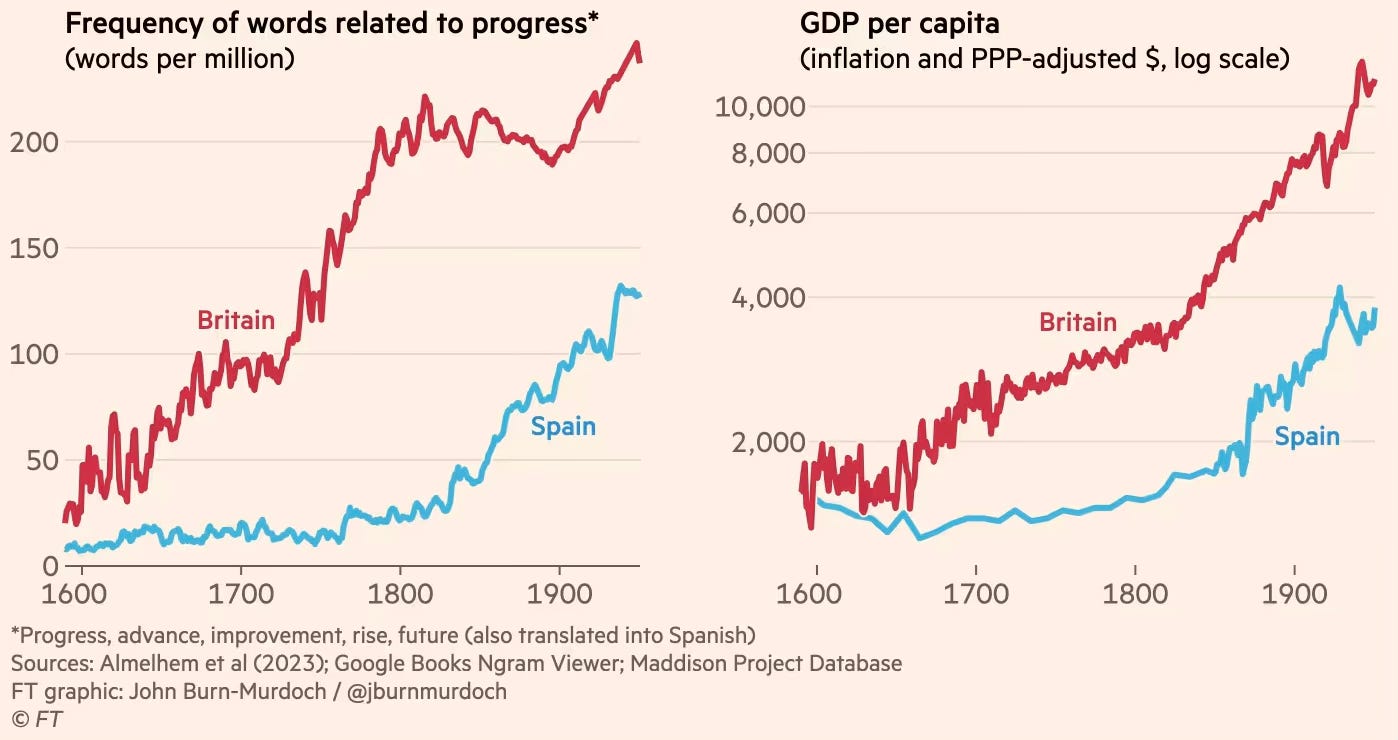

To explore whether this holds for other countries, I have adapted and extended their analysis to include Spain, which was economically competitive with Britain well into the 17th century, but then fell behind. Using data from millions of books digitised as part of the Google Ngram project, I have found that the upsurge in discussions of progress in British books occurs about two centuries before the same uptick in Spain, mirroring trends in the countries’ economic development.

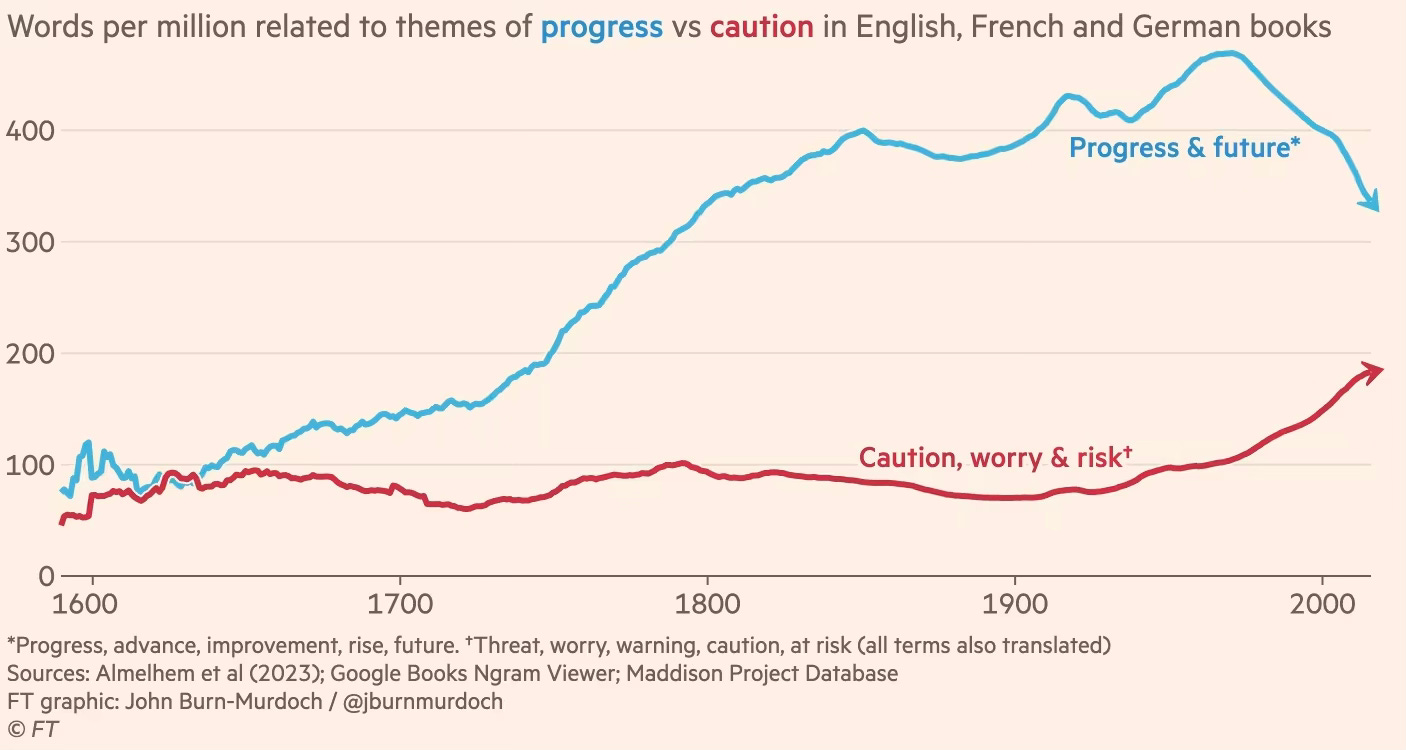

Burn-Murdoch goes further and finds that in contrast the language and culture of today appears to be regressive,

Extending the same analysis to the present, a striking picture emerges: over the past 60 years the west has begun to shift away from the culture of progress, and towards one of caution, worry and risk-aversion, with economic growth slowing over the same period. The frequency of terms related to progress, improvement and the future has dropped by about 25 per cent since the 1960s, while those related to threats, risks and worries have become several times more common.

That simultaneous rise in language associated with caution could well be not a coincidence but an equal and opposite force acting against growth and progress. Ruxandra Teslo, one of a growing community of progress-focused writers at the nexus of science, economics and policy, argues that the growing scepticism around technology and the rise in zero-sum thinking in modern society is one of the defining ideological challenges of our time.

The authors of the IZA paper have three findings,

First, there is little overlap in scientific and religious works in the period under study. This indicates that the “secularization” of science was entrenched from the beginning of the Enlightenment. Second, while scientific works did become more progress-oriented during the Enlightenment, this sentiment was mainly concentrated in the nexus of science and political economy. We interpret this to mean that it was the more pragmatic works of science—those that spoke to a broader political and economic audience, especially those literate artisans and craftsmen at the heart of Britain’s industrialization—that contained the cultural values cited as important for Britain’s economic rise. Third, while volumes at the science-political economy nexus were progress-oriented for the entire time period, this was especially true of volumes related to industrialization. Thus, we have unearthed some inaugural quantitative support for the idea that a cultural evolution in the attitudes towards the potential of science accounts in some part for the British Industrial Revolution and its economic takeoff.

Joel Mokyr has written about the sudden and miraculous explosion of science and technology in one part of the world and the creation of conditions for long-term economic growth, a development that cannot be explained by institutions alone. He points to the importance of culture - beliefs, values, and preferences that can change behaviour - in laying the foundations (in the 1500-1700 period) for the scientific advances and pioneering inventions that would instigate explosive technological and economic development.

I concentrate primarily on the one element in cultural beliefs that economists have so far neglected almost entirely, namely the attitude toward Nature and the willingness and ability to harness it to human material needs. Ultimately the relations with makom, or the physical world around us in the end determine the growth of useful knowledge and eventually that of technology-driven growth.

Technology is above all a consequence of human willingness to investigate, manipulate, and exploit natural phenomena and regularities, and given such willingness, the growth of the stock of knowledge that underpins and conditions the exploitation of knowledge. The willingness and ability to acquire, disseminate, and harness such knowledge are themselves part of culture and thus determine the intensity of the search for knowledge of nature, the agenda of the research, the institutions that govern the community doing the research, the methods of acquiring and vetting it, the conventions by which such knowledge is accepted as valid, and its dissemination to others who might make use of it.

It is in this general area that the roots of modern economic growth should be sought—specifically in events and phenomena that precede the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution in the centuries that are known, for better or for worse, as “early modern Europe,” roughly speaking between the first voyage to America by Columbus and the publication of the Principia Mathematica by Newton. It is the basic argument of this book that European culture and institutions were shaped in those centuries to become more conducive to the kind of activities that eventually led to the economic sea changes that created the modern economies.

He points to the different ways in which cultural beliefs create the conditions for adoption of technology.

The most direct link from culture and beliefs to technology runs through religion. If metaphysical beliefs are such that manipulating and controlling nature invoke a sense of fear or guilt, technological creativity will inevitably be limited in scope and extent. If the culture is heavily infused with respect and worship of ancient wisdom so that any intellectual innovation is considered deviant and blasphemous, technological creativity will be similarly constrained. Irreverence is a key to progress… so, as Lynn White has pointed out, is anthropocentrism. In his classic work, White stressed the importance of a belief in a creator who has designed a universe for the use of humans, who in exploiting nature would illustrate His wisdom and power… social attitudes toward production and work (and leisure) are another major factor in determining the likelihood of innovation.

Technologically progressive societies were often relatively egalitarian ones. In societies dominated by a small, wealthy, but unproductive and exploitative elite, the low social prestige of productive activity meant that creativity and innovation would be directed toward an agenda of interest to the elite. The educated and sophisticated elite focused on efforts supporting its power such as military prowess and administration, or on such topics of leisure as literature, games, the arts, and philosophy, and not so much on the mundane problems of the farmer in his field, the sailor on his ship, or the artisan in his workshop… The agenda of the leisurely elite was of great importance to the lovers of music in the eighteenth-century Habsburg lands, but was not of much interest to their farmers and manufacturers. The Austrian Empire created Haydn and Mozart, but no Industrial Revolution. As McCloskey has stressed, the bourgeois societies of the Netherlands and Britain of the seventeenth century, in contrast, were prime candidates for technological advances.

I’ll blog longer about Mokyr’s book that I just finished reading in another post. His analysis, coupled with that of Tirthankar Roy, have interesting implications if we examine India’s historical industrial development pathway.

No comments:

Post a Comment