1. NYT has an article on how the Russian government facilitated a massive wealth transfer in the process of facilitating the sale of western multinational corporation's businesses in Russia in the aftermath of the Ukraine invasion.

Mr. Putin has turned the exits of major Western companies into a windfall for Russia’s loyal elite and the state itself. He has forced companies wishing to sell to do so at fire-sale prices. He has limited sales to buyers anointed by Moscow. Sometimes he has seized firms outright. A New York Times investigation traced how Mr. Putin has turned an expected misfortune into an enrichment scheme. Western companies that have announced departures have declared more than $103 billion in losses since the start of the war, according to a Times analysis of financial reports. Mr. Putin has squeezed companies for as much of that wealth as possible by dictating the terms of their departure. He has also subjected those exits to ever-increasing taxes, generating at least $1.25 billion in the past year for Russia’s war chest.

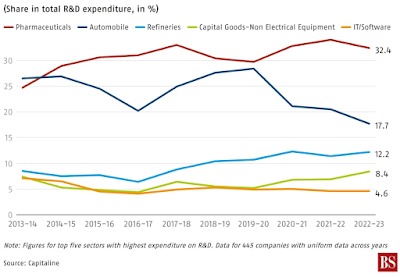

2. Business Standard reports that the R&D expenditures of Indian companies has been declining as a share of their net sales. It examined 445 S&P BSE 500 companies who spent Rs 651.3 trillion in the last decade of which less than one percent went into R&D.

Companies in the United States spent the most on R&D (investing 8.1 per cent as a proportion of their net sales) in 2022. Chinese companies were the second biggest spenders (3.8 per cent) and the Japanese (3.8 per cent) came third. It was 1.7 per cent for Indian companies, according to data from the Economics of Industrial Research and Innovation.

3. TN Hari in Livemint has a long read where he questions the incremental value of big data in most contexts. He illustrates the example of BigBasket.

On an e-commerce platform like BigBasket, when you scroll down the list of ‘frequently purchased items’ to place your order, there would be a couple of items that are ‘recommended’ for you. Typically, the number of recommendations is around 5% of the items in the frequently purchased list of items. And the success rate—defined as the per cent of recommended items actually purchased by the customer—is around 2%. In other words, the increase in the order value because of recommendations is nearly a tenth of a per cent (2% of 5%).Therefore, if your basket size is a thousand rupees, all that this data crunching and insights engine is achieving is to increase it by a rupee. Doing anything that increases the basket value of a customer is perfectly understandable as long as the cost of doing it is insignificant. Hence, it is not a bad idea to make a small one-time investment to build a recommendation engine, but making a big noise about how crunching big-data can transform your business, at least in this context, is a bit far-fetched.

He questions the value of data analytics in the well-known settings.

The ad-income model has created some wildly successful companies such as Facebook and Google. Amazon has also monetized its customer base to generate a decent income. The truth though is that companies like Google and Facebook are somewhat of an exception and a rarity. Building a business with the hope of monetizing, à la Google or Facebook, is extremely risky and naive. All other platforms with a customer base (or reader base) have struggled to earn ad-income. Most readers tend to skip ads, and the effectiveness of algorithms that drive the real-time placement of ads is highly questionable. There is also a growing realization that the only beneficiaries of Facebook and Google ads are Facebook and Google.The ability to personalize ads is questionable. This writer has come across many friends and colleagues who continue to be highly amused by the jobs that LinkedIn keeps recommending for them based on its interpretation of their profiles and online activity. The recommendations don’t come anywhere near what they would be interested in... The business model of most fintech companies hinges on being able to evaluate the creditworthiness of borrowers accurately and quickly. The belief is that it would lower defaults. Successful lending has always been a trade-off between not lending to good borrowers (because of some wrong red flag) and lending to bad borrowers (because no red flag came up).

His summary is brilliant,

Crunching big data is somewhat akin to creating better image resolution... Unless the enhanced resolution results in recognition of new patterns that were not discernible at lower resolution with lesser data, there is no advantage of crunching this humongous data. And even if you assume that some additional patterns do show up, there is the non-trivial problem of monetizing them. This is where the universal Pareto principle kicks in, which is, 80% of patterns are evident with 20% of the data. Beyond this is the valley of severely diminishing returns. When you have a hammer in your hand, everything looks like a nail. In this case, the hammer is computing power.Nothing can substitute for a deep understanding of your target group of customers and good execution. Someone wise had once said that when there is a gold rush the ones who make money are not the gold diggers but the ones selling shovels. And ironically, it is the gold diggers who always make the most noise about how the power of the new shovels would make them all very rich. When there is a rush to create and monetize customer data, the ones who make money are not the companies that wish to monetize their customer data but the ones selling computing capacity.The science of thermodynamics is based on the premise that everything that matters about a gas can be understood without having to crunch data on the positions and velocities of the individual molecules.

4. Brilliant set of graphics on the power of compounding and other financial savings insights. This graphic on the percentage of gains required to recover from a loss.

My research shows that a rate of growth in the working-age population of at least 2 per cent is a necessary condition for “miracle” economic growth, implying a sustained pace of at least 6 per cent. As of 2000, 110 countries had a working-age population growth that fast, nearly half in Africa. Now there are just 58, with 41 or more than two-thirds in Africa... Over the past five years, only three of the 54 African economies have grown at an annual rate of more than 6 per cent: Ethiopia, Benin and Rwanda. That is down from 12 in the 2010s. Not a single African economy has seen a transformative gain in average per capita income, and half have seen a decline, including three of the continent’s five largest countries — Nigeria, South Africa and Algeria. Africa is adding workers but not increasing output per worker.

6. Interesting snippet about donor funding of US universities

The US Council for Advancement and Support of Education calculates donations to US universities in 2022 were $60bn, including 14 per cent from those who gave at least $25mn each... the funding of American higher education, with once state-funded public institutions increasingly reliant on powerful donors like their elite, private, non-profit peers in the Ivy League... a longer-running discussion about the operation of university boards, including who is selected, how long they should serve, what their responsibilities should be, and how their relationships should be managed with a larger circle of donors...

Many universities have established sprawling boards with dozens of members, partly to cultivate and engage donations. MIT has 74 board members, while Cornell has 64. Harvard has a 12-strong corporation and a broader board of 32 overseers. Board members sometimes come from a narrow range of fields and many do not have academic backgrounds... Penn’s board has 48 voting participants, and a further 36 longstanding emeritus members who have reached the retirement age of 70 but are still allowed to attend and speak at meetings. Most are drawn from finance, including many who made large fortunes on Wall Street... “they are people especially from private equity and the hedge fund world who are used to getting their way in life”, and are “clubbable types” who frequently interact with each other and other donors, making them vulnerable to pressures beyond the Penn boardroom. “Trustees do have a bit of a conflict between their business, social and personal lives.”

Given how needlessly beholden the universities have become to Wall Street interests and the questionable governance structures, no wonder that US universities are now being blackmailed by vain and loud donors like Bill Ackman and Marc Rowan.

This is a good long read on the issue.

7. Is TSMC contributing to Dutch Disease in Taiwan?

As of December 8, TSMC accounted for 26.8 per cent of the Taiwan Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation... Ko Wen-je, the former Taipei mayor who is challenging Taiwan’s largest two established parties, the DPP and the opposition Kuomintang, in the presidential race, also claimed that Taiwan was suffering from the “Dutch disease”. He pointed to a growing gap in investment and incomes between its tech sector and the rest of the economy... Economists agree that Taiwan’s economy is growing too lopsided. In the past two years, semiconductors accounted for almost 42 per cent of exports, up from about 33 per cent in 2016 when president Tsai Ing-wen and her Democratic Progressive party came to power...

The services sector which provides the majority of jobs — it employs 4.8mn people compared with just 663,000 in the chip industry — is languishing because sluggish consumption during the pandemic has weakened its mostly small companies... According to TSMC’s 2022 ESG report, the company, including a handful of overseas plants, consumed 21,056GWh of electricity, equivalent to 7.5 per cent of Taiwan’s entire power consumption last year.

8. Pharmaceutical drug of the year should undoubtedly be Novo Nordisk's Wegovy and Ozempic. This is a very good profile of Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen, the understated CEO of the company. The company's blockbuster diabetes treatment drugs have become game changers in obesity treatment and have the promise to prevent heart attacks and also treat Alzheimer's disease by reducing inflammation in the brain.

Fatima Cody Stanford, an expert in obesity medicine at Harvard Medical School, says the drugs will be “highly influential” and may lead to a decline in the need for treatment for conditions such as hypertension, kidney disease, fatty liver disease, diabetes and sleep apnoea. Novo Nordisk is running a late-stage trial to see if semaglutide could treat the widespread neurodegenerative disease Alzheimer’s, and external researchers are also intrigued about the potential for the drugs to be used to treat alcohol addiction.

The article points to the long-gestation of the development of these drugs,

The drugs began life at Novo Nordisk 32 years ago — by coincidence, when Jørgensen joined the company. Wegovy and Ozempic are both made from semaglutide, a version of an appetite-reducing hormone called GLP-1. But in the body, the hormone only lasts for minutes, so Novo’s scientists spent years making it stable enough to use as a medicine. Jørgensen’s time at the company has coincided with a long-term bet on the potential of this new science. The first real breakthrough came 14 years ago, when the drugmaker got its first approval for a GLP-1 drug for diabetes in 2009. Another version followed in 2015, targeting weight loss. But it only helped patients lose about 5 per cent of their body weight. It would take six more years until Wegovy was approved, after a trial showed an average of 15 per cent weight loss.

And how the company ownership structure allowed it to take the long-term view.

Novo Nordisk could invest for the very long term partly because of its unusual ownership structure. Initially called Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium, the company was founded in 1923 by the Danish Nobel laureate August Krogh, pharmacist August Kongsted and scientist Hans Christian Hagedorn. The Canadian scientists who discovered insulin granted the pair permission to produce it in Scandinavia, with a caveat: the proceeds from its sale should be reinvested in research. So they set up the Novo Nordisk Foundation, which thanks to the company’s growth is now the world’s largest philanthropic foundation by assets. Novo Holdings, which manages the foundation’s wealth, has 77 per cent of the voting rights of Novo Nordisk. Martin Jes Iversen, an associate professor of strategy and innovation at Copenhagen Business School, says the structure kept the company committed to its broader purpose beyond profitability. It also ensured Novo Nordisk was not for sale.

This is a list of other medical conditions that such semaglutides like Ozempic might be able to treat. They include alcohol abuse disorder, polycystic ovary syndrome, liver disease, cardiovascular issues, sleep apnea, and kidney disease.

9. If the proposal by Nippon Steel to buy the ailing US Steel for $14.9 bn is rejected on political grounds, as is being demanded by leading US politicians on national security grounds, then it should count as protectionism becoming mainstream in the US politics. As an FT columnist wrote,

The now bipartisan American backlash against Nippon Steel’s $14.9bn purchase of US Steel — a deal driven by robustly commercial motives and for which the Japanese buyer is shelling out roughly twice what a US bidder was prepared to pay — appears to be shaped by the idea that even close friends merit suspicion... If Nippon Steel’s deal is approved, it will draw a mid-ranked American company under the umbrella of one of the world’s top three steelmakers, none of which is American. Specifically, it will make that company more competitive with Chinese rivals (that are genuinely state-owned) in an era where that battle is the greater threat. The tougher question, though, is that of trust. If Japan does not count as a legitimate buyer of assets in the US, who does?

10. Finally, Martin Wolf has a set of sobering graphics about the indebtedness among the 75 low income countries eligible for assistance from the World Bank's soft-loan arm, IDA. The risk of debt distress has soared among these countries, with 28 countries eligible to borrow from IDA now at high risk of debt distress and another 11 in distress.

No comments:

Post a Comment