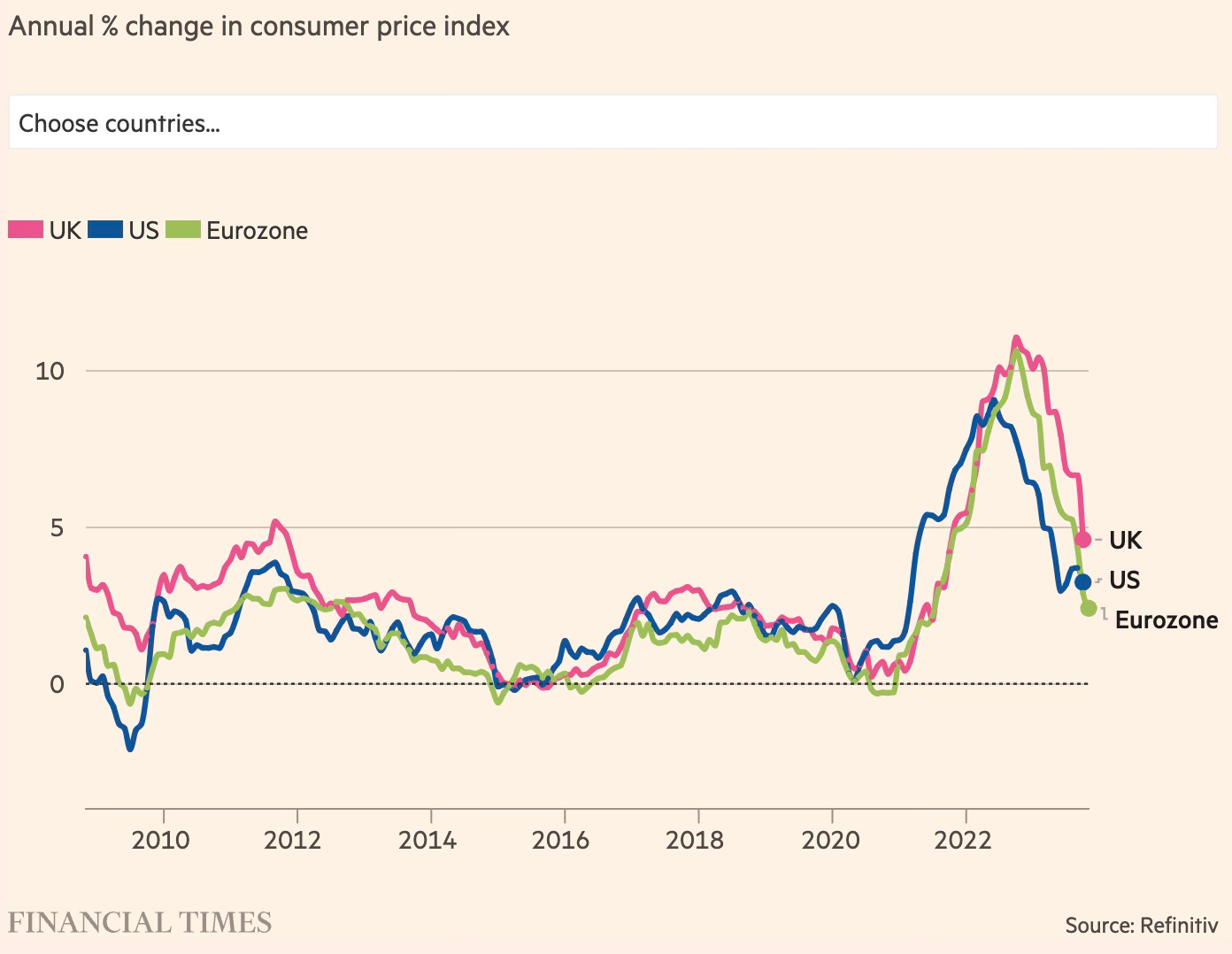

As the year winds down, it's becoming clear that inflation is trending downwards. This has in turn posed inevitable questions to central bankers. Is the downward trend definitive and sufficient enough to merit rate cuts? And if so when should the rate cuts begin? And once they begin there would be questions about the pace and extent of cuts. These questions will all acquire great significance in 2024, as much as questions about how many more rate rises that central bankers faced in the first half of 2023.

From hindsight, it's now clear that the central banks under-estimated the inflation impulses that emerged from the combination of pandemic and Ukraine war induced supply shocks and the demand resilience/spurts from the massive pandemic fiscal stimuluses and post-pandemic revenge spending. They went along with those group of economists who believed that the spike in inflation would be transitory and would reverse on its own once the shocks receded. But as we know now, the stimulatory effects more than offset the contractionary supply-side forces. The shocks while temporary had sowed seeds of a wage-price spiral. Complementary trends like the reduction in labour market participants (the Great Resignation etc, even if they were temporary as it appears) amplified the spiral.

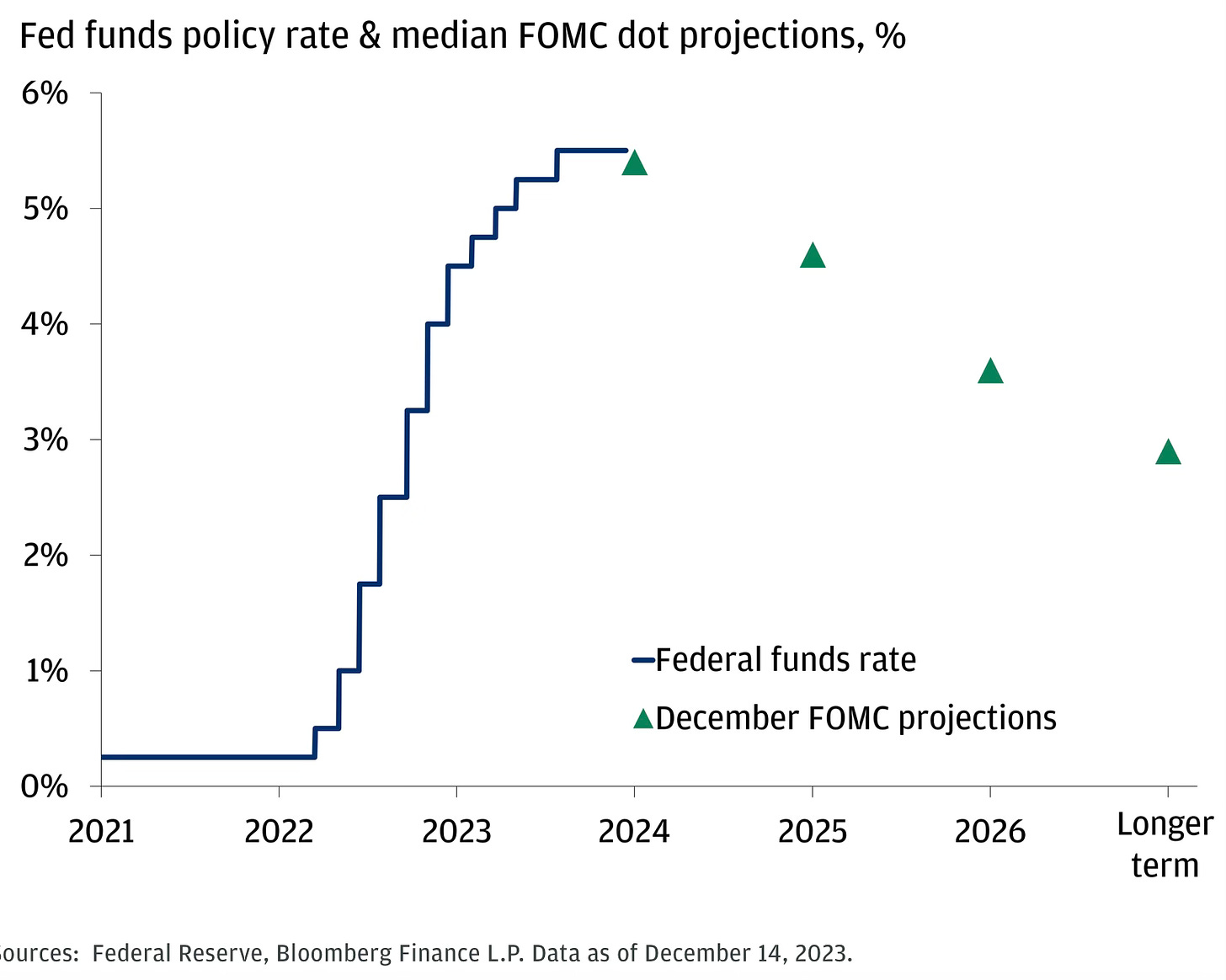

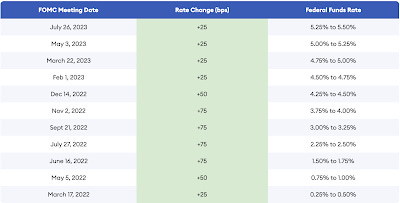

Once inflation continued to surge and hopes of any immediate reversal receded, the US Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) started raising rates from mid-March 2022 and immediately signalled six more increased during the year. And it undertook 11 consecutive rate rises over 16 months till late-July 2023 when it signalled pause. It included four increases by 75 basis points and two of 50 basis points. The rates rose from the 0-0.25% band to 5.25-5.50% band, the highest since 2001.

While the Fed was clearly behind the curve in responding to the rising inflation, it made up with an impressive display of resolve with its rapid response since March 2022. Therefore, as Larry Summers has commented, if there's a soft landing, the Fed should take all the credit for its decisive, rapid, and large enough rate increases by 5 percentage points. Summers has described the Fed's actions "in the two years after 2021 were a less than 1 per cent probability set of actions relative to what the market expected".

It now faces the challenge of not falling behind the curve in cutting rates.

But while it seems to have got right the decision to call the rates have peaked, there's a strong argument that its forward guidance on this count may have gone too far prematurely. Mohammed El Erian made the point that the Fed's dovish remarks in the latest FOMC may be leading it down a slippery slope of shaping market expectations that favour accommodation.

The more the Fed gives in to investor expectations for sizeable and early rate cuts in 2024 — including getting closer to the six cuts priced in for next year — the more the markets will press for an even more dovish policy stance. If investors price in additional rate cuts, it is harder for the Fed to pursue its mandate without a big market reaction. The Fed’s divergence with the market will prove hard to fix quickly while its policy divergence with the Bank of England and European Central Bank will widen. The more this continues, the greater the risks to economic wellbeing and financial stability.

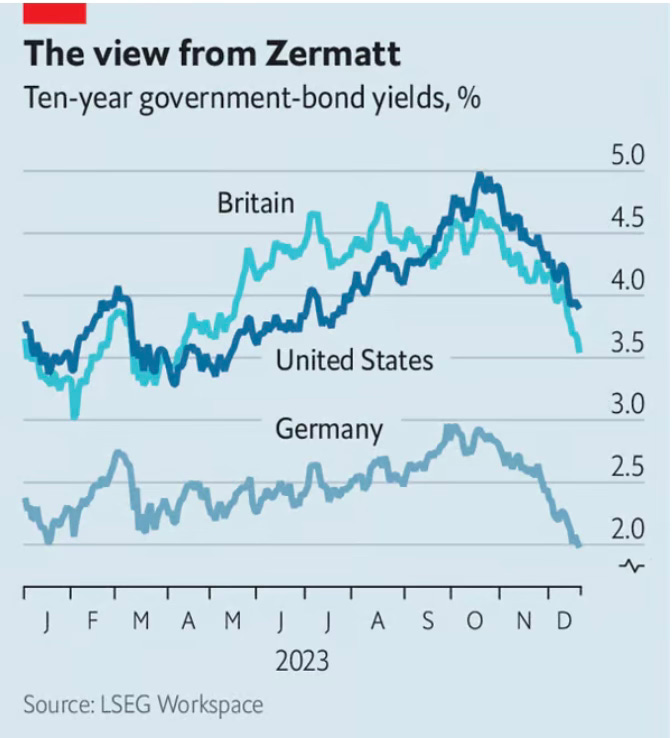

In fact, there are already signs of heightened expectations among market participants. Following Jerome Powell’s last FOMC press meet on December 13, the markets have surged and bond yields have dived.

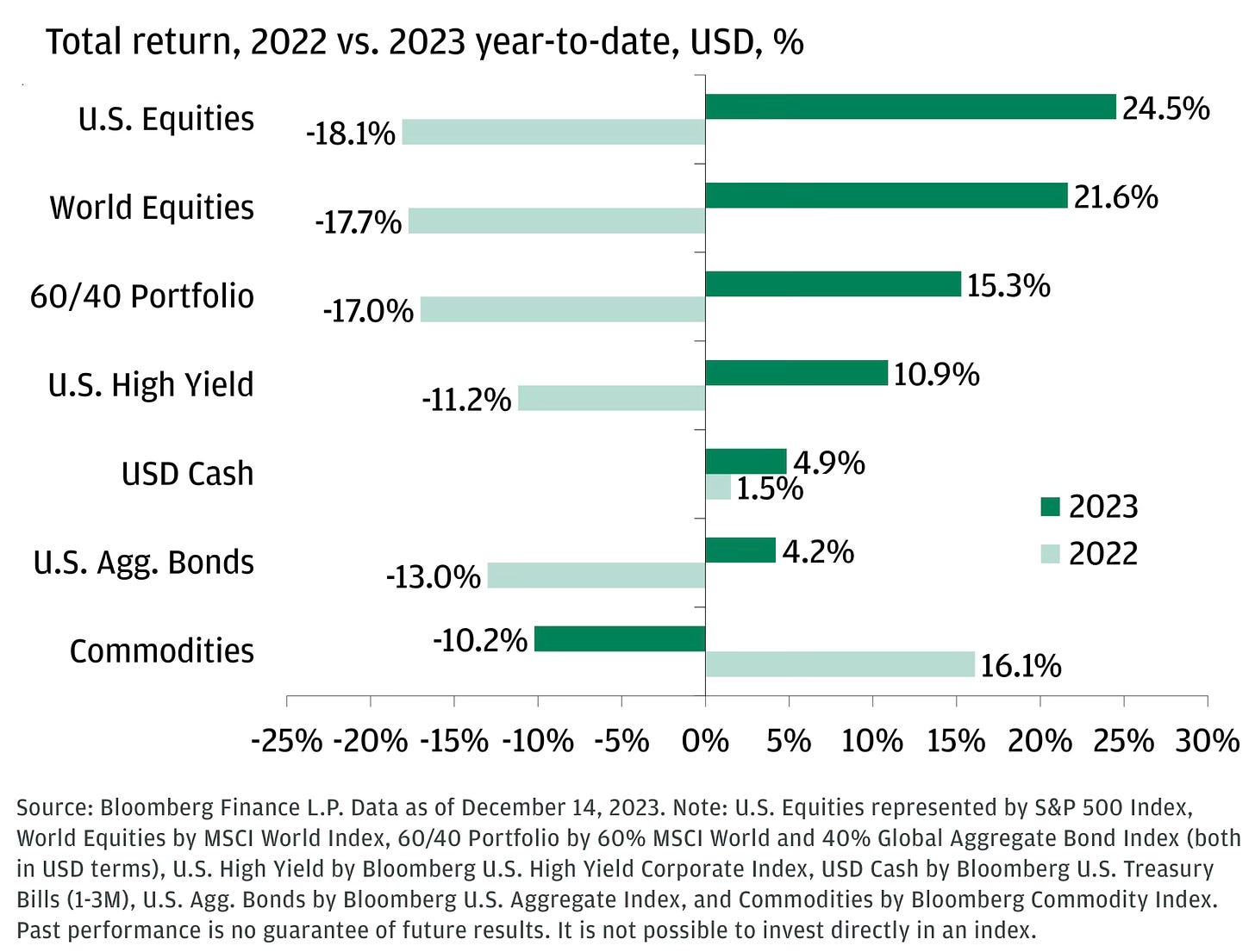

Analysts and investors scrambled to catch up, pencilling in rate cuts earlier than they had previously predicted, and in much greater number. Subsequent efforts by Fed officials to cool market exuberance have had little impact. Swaps markets show some investors are looking for six quarter-point rate cuts next year, against guidance from the Fed for a potential three. Such market measures are not perfect, and could mean that most investors are anticipating two or three cuts but a smattering of hedging for extreme outcomes is bending the median out of line… Since those pronouncements from the Fed, yields have lurched lower, sinking well under 4 per cent and blasting through many of Wall Street analysts’ forecasts for where they might end 2024. The impact fanned out across other major government bond markets and sent stocks motoring higher. “What the Fed delivered in terms of message was not a big shock. The market reaction was more of a shock,” said Vincent Mortier, chief investment officer at Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager… Days after Powell’s comments Goldman Sachs, which had already set a target of 4,700 for the S&P 500 for the end of 2024, raised that forecast to 5,100, seven per cent above prevailing levels.

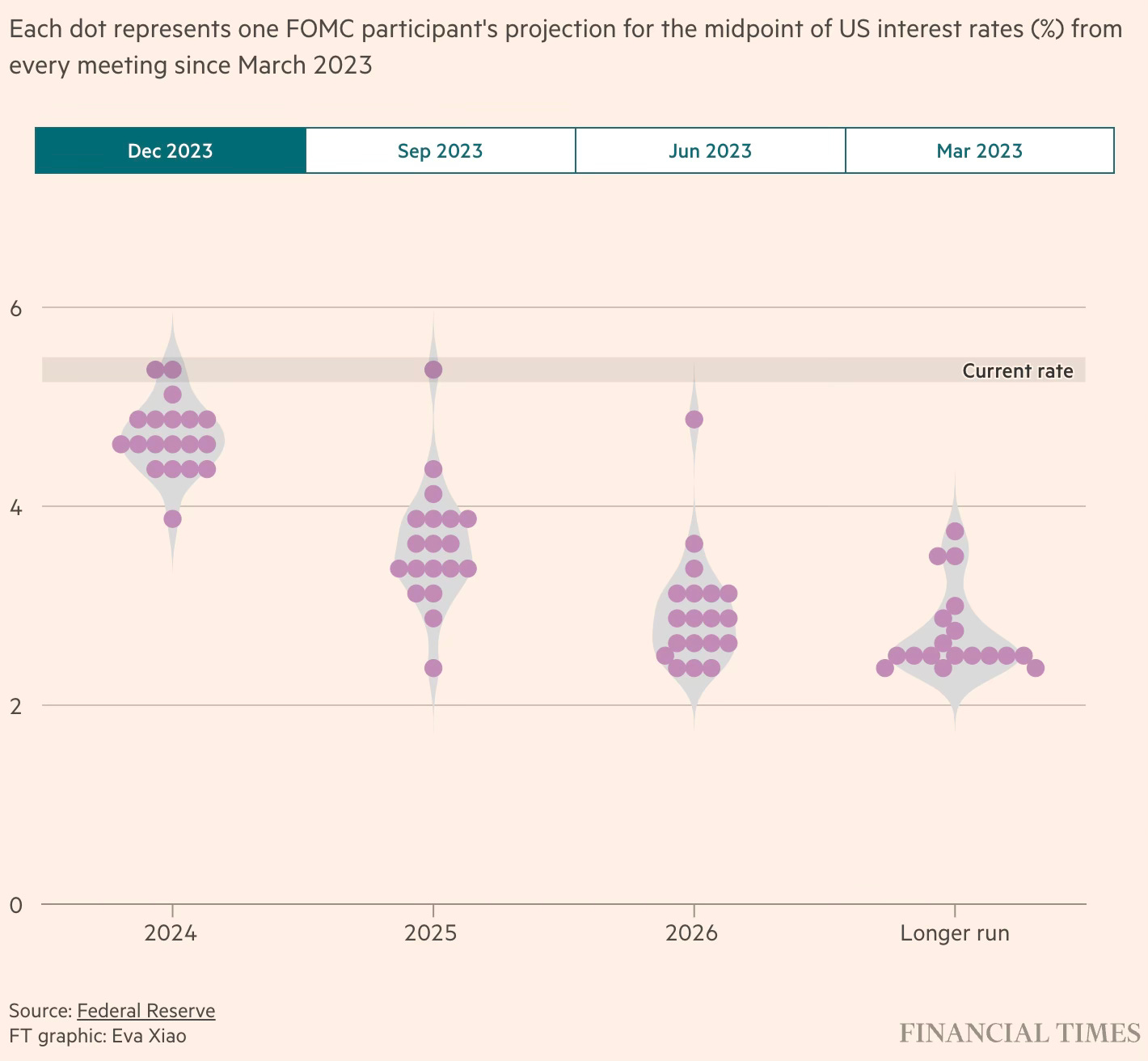

In this context, Summers questions the wisdom of forward guidance and says that it's a case of transparency gone too far with monetary policy communications.

I think the Fed has done itself considerable damage by putting as much emphasis on forward guidance and transparency as it has. I [prefer] the Volcker/Greenspan approach, which is to recognise that the Fed is a little bit like the Delphic oracles. People regarded them as omniscient and omnipotent, but they were in fact neither. So the oracles kept their pronouncements vague and oracular, not concrete and specific, because it was impossible to be concrete and specific without being wrong frequently and undercutting credibility. So I think that the Fed has had a problematic approach to financial communications.

The two most successful bits of financial communications in the last generation, I would argue, were both of an entirely non-dot-plot or forward guidance variety. They were Mario Draghi’s statements about “whatever it takes”, and Bob Rubin’s “the strong dollar is in the national interest”, both of which qualified as general and oracular. So I would be endeavouring to not constrain myself substantially with any set of predictions or attempt to lay out my reaction function, because I would recognise that events would come in ways that I wouldn’t anticipate, and that I would run the risk of trouble. Another way to say it is: forward guidance is a bit of a fool’s game. The market doesn’t especially believe it and the Fed feels constrained by it down the road.

But on the issue of Fed falling behind the curve in combatting inflation, academic and outside critics may be discounting the real-time practical challenges faced by central bankers as they were forced to respond to the emerging inflation trends. Sam Fleming in FT has a good interview of Charles Goodhart, where he highlights the problems faced by central banks in responding quickly to the rising inflation in 2021.

In Bank of England policymaker Jonathan Haskel’s excellent speech he says that they had to wait until December 2021 because they feared that there would be a massive increase in unemployment when the workers came flooding back after the furlough. And Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell makes much the same argument... Haskel’s work on this uses the modelling that former Fed chair Ben Bernanke and former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard developed — transposing it to the UK. It says there was an initial burst of inflation during the spring and summer of 2021, and that was from energy prices and shortages, and that the labour story kind of picks up later. And so it was reasonable of them to say this is transitory...

They didn’t see that Covid had itself reduced the likelihood of a large return of labour. And they didn’t see that the underlying trend was strongly against a significant increase in the labour force... the decisions they made in the summer of 2021 that they could hold interest rates at very low levels. It was in the second half of 2021 that inflation really began to get going quite rapidly and well before the Ukraine attack by Russia... I think that Blanchard and Bernanke, and Haskel and his colleagues overstate the supply side shortage argument. It’s my guess that quite a lot of what they attribute to shortages actually is much more attributable to the fiscal expansions that were occurring at more or less the same time.

Goodhart also questions the central bank's dot-plot forward guidance,

With the dot plots is this what they would like to happen? What they think will happen? Do you estimate future interest rates depending on how you think your colleagues are going to vote or do you estimate the future interest rates on what you think ought to happen? Exactly what do they represent? It’s not really clear.

Goodhart makes a point on short-term inflation trends.

There’s absolutely no doubt that inflation got exaggerated by the supply shocks, oil and particularly gas in Europe and the UK, which America didn’t suffer to anything like the same extent. So when that reverses, you’re bound to get quite a sharp decline. But the underlying core and labour market inflation has not yet got down to the target level. My expectation is that 2024 will look very nice because we’re having a reversal of the upsurge in energy prices. And if, as I think is quite possible, there is some kind of truce in the Ukraine war, energy prices might come down even further. And I think 2024 will look good. I think the central banks will declare victory and at some point will start lowering nominal interest rates. My concern is the catch-up argument. The desire of households to restore living standards to what they were earlier, will mean that particularly if interest rates do go down, the labour market will remain tighter than is consistent with underlying target inflation. So 2025 will actually see some reversal, with inflation going up again, maybe even towards the end of 2024...

The concern about catch-up is cumulative. It’s not just ‘did we misestimate inflation now?’ It’s a question of ‘how far have our living standards fallen, compared to a reasonably recent past, which we thought in some sense was normal?’ So it’s a cumulative decline in living standards that I think is crucial. You’ve only got to look at what the striking doctors and nurses, railwaymen and so on say now, to realise it’s cumulative. Moreover, UK real living standards have been further reduced by the fact that effective tax rates have been increased in the meantime by keeping the thresholds constant. So if you take real post-tax living standards, many, particularly in the public sector, are suffering a considerable cumulative reduction in their standard of living. I would argue that the actual variable that [Haskel et al] use to model catch-up is not, in my view, sufficient or satisfactory...

It’s a very difficult period for central banks. If headline inflation gets down to or below 2 per cent, as is perfectly possible during the course of 2024, and unemployment is rising, and you have got general elections coming along so politicians are unhappy if you don’t cut interest rates, I think the pressure on central banks during 2024 to cut nominal interest rates will be overwhelming. And I would understand entirely if they do so. I think my only comment would be that if and when — and I think it’s a question of when rather than if — inflation then starts rising again towards the very end of 2024 or into 2025, as the reduction in energy prices itself falls out of the headline CPI, they’ve got to be ready to reverse tracks again.

Given all these some thoughts:

1. I'm a bit surprised by the debates on inflation revolving so tightly around the 2% target. As has been well documented, the 2% target is not based on any objective scientific principles and owes its current importance to Ben Bernanke's decision in 2012 to make it the stated inflation target. This has since taken the nature of something sacrosanct. Not even the problems with deflation last decade appears to have shaken this 2% inflation target.

As economies were stuck with deflation and the zero lower bound in interest rates, Olivier Blanchard had led a small group of influential economists to question the wisdom of the 2% inflation target and suggested instead that it be raised to 4%. The IMF too expressed its sympathy with this view. In fact, in August 2020, in a small concession, the FOMC adopted a flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT) regime wherein the objective means achieving an inflation target (the same 2%) which is average over time. It implied that if the inflation was running persistently below the target, the FOMC will aim at an inflation moderately above the target for some time to return to the target of 2%. But now with inflation declining and debates raging on when to start cutting rates, the 2% inflation target appears to have resurfaced with a vengeance.

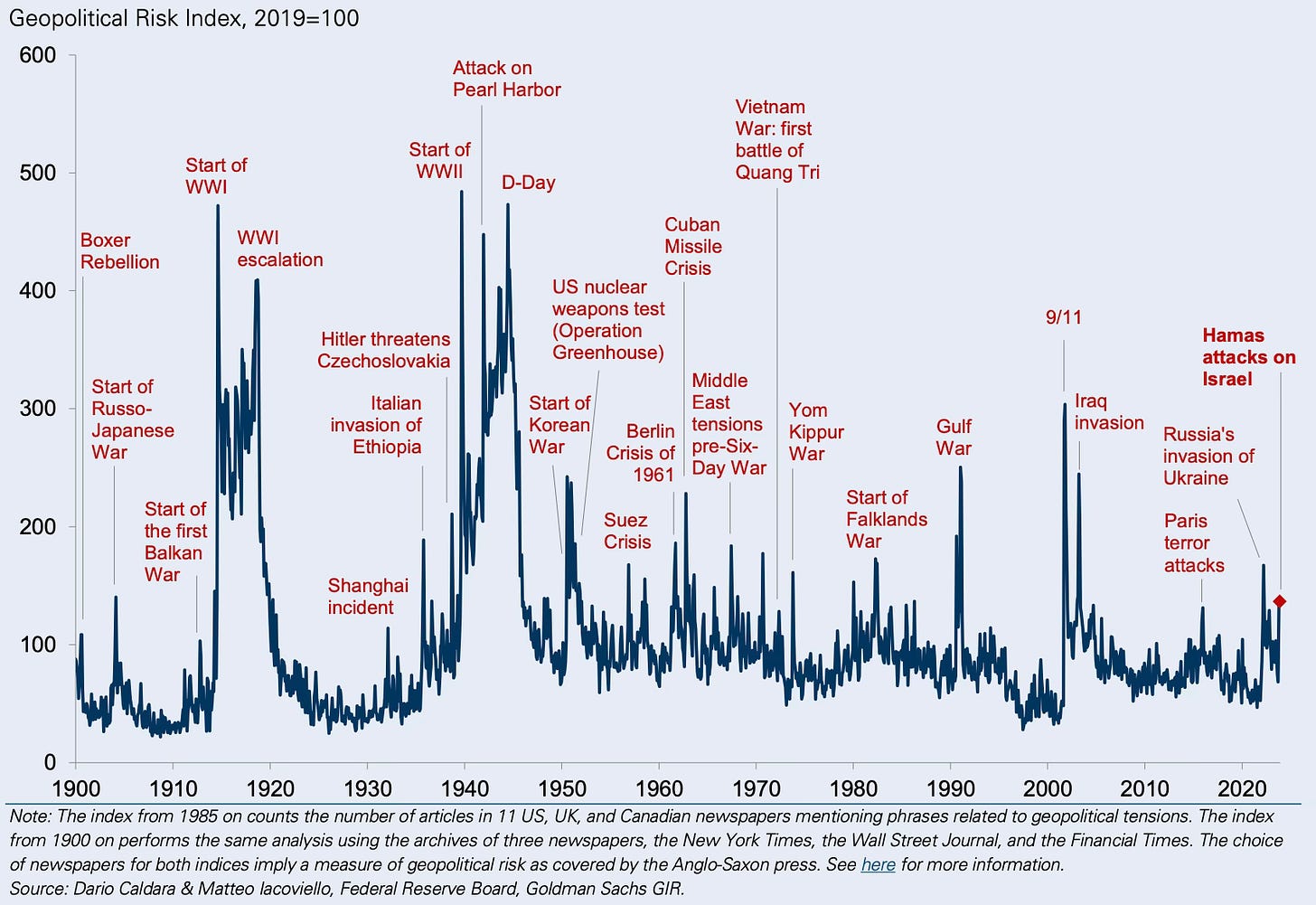

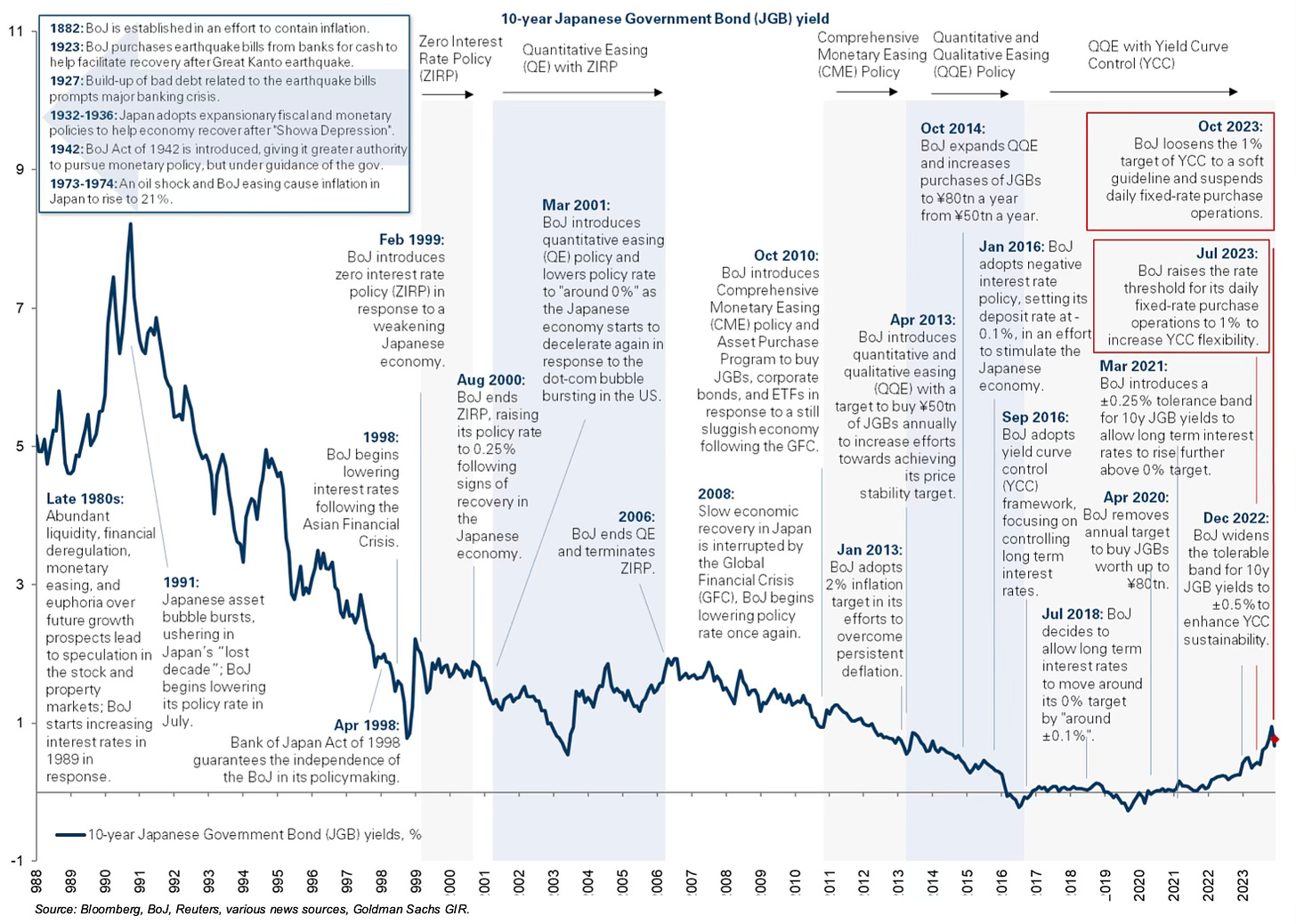

The persistence of the 2% inflation target may be a reflection of the hankering of the markets and policy makers to get back to the economic conditions of the last two decades and the belief that ultra-low rates, low inflation, high growth rates, and booming financial markets can all co-exist together. This goldilocks state of the world economy may have been an exception and we may now be seeing a reversion to the norm. There are several factors pointing to the normalisation of inflation trends - end of the China effect and globalisation on inflation, rising protectionism, increased labour market tightness, rising geopolitical uncertainties especially from the new Cold War etc.

2. Also surprising is the absence of financial market stability considerations in the debates on monetary policy actions despite all the convulsions of the last four years. The commentary on monetary policy response to inflationary trends continue to be dominated by the macroeconomic indicators - labour markets, consumer sentiments, goods and services output etc. Where do the financial market conditions fit into the objective functions of central banks? Even as inflation rate declines and other macroeconomic indicators point to a cooling economy, how does the Fed view the resurgent financial markets which appear to be clearly irrationally exuberant? Where does it fit in the Fed's objective function on rate setting?

This will become even more important as the rate cuts start. The markets having internalised the ultra-low rates as the norm will invariably demand a return to those levels. Assuming inflation remains range bound or even falls to below the 2% target, the pressure will mount on the Fed to keep cutting below what's required and to levels that will engender financial instability. The over-leveraged governments and policy makers too will favour such rate cuts. In the circumstances, where does the Fed draw the line on what's an acceptable interest rate?

It's therefore important that the Federal Reserve factor in financial market conditions in its monetary policy decisions also because a likely soft economic landing coupled with the ongoing frenzy on new technologies like artificial intelligence may be creating the conditions for further increases to an already heavily over-priced equity markets. The financial markets may have internalised expectations that the Fed will not allow major convulsions in the run up to the 2024 elections and will lose no opportunity to pressure the Fed before every FOMC meeting next year to be a bit more accommodative than it would otherwise have been.

It's ironical that Fed may have become even more beholden to financial market signals despite all the events of the last couple of years and the volatility surrounding them.

3. The point here is that the Fed’s decision on rate cuts should not be premised on the 2% inflation target which was decided in a period of low inflation rates, but a slightly higher inflation rate consistent with a return to more normal inflation rates. Further, especially given the extent of influence that financial markets appear to exercise over Fed decisions, it may be time to think about the possibility of explicitly factoring in some range-bound parameters of financial market conditions in the Fed’s rate setting decisions.

4. There is a strong case that the most important factor for Fed to consider while deciding when to cut rates may be the financial market conditions. The wealth effect from rising equity markets and cheaper lending from falling bond yields risks fuelling inflation. In other words, the financial market conditions may drive the reversal of the current declining inflation trend.

5. There are other problems with forward guidance than the one highlighted by Summers. For one, uncertainty may have some virtues. The former Fed Governor Donald Kohn has argued that through its forward guidance the Fed may be communicating more certitude to the markets than may be appropriate.

Mr. Kohn believes that some of the ways the Fed now communicates to markets—by way of its “dot plot” of interest-rate projections, as well as its other forecasts—have come to be viewed as more certain than they are. He believes the Fed, both in the presentation of these views and in the remarks of officials, has reinforced the certainty of its outlook, even when officials already know much about the future is unknowable. The Fed’s quarterly forecasts should be aligned with “the rhetoric of uncertainty and data dependency and the true state of economic knowledge,” Mr. Kohn said. The Fed should stop summarizing key projections with medians, and portray the amount of uncertainty the Fed has around its various forecasts.

There may be merit in asymmetric ignorance of monetary policy in disciplining the financial markets and ensuring that investors exercise vigilance and due-diligence in their investment decisions. Forward guidance appears to be getting blunted in an age where expectations are baked in that central banks will backstop equity markets. For example, “it took months of persuasion for investors to get the message from monetary policymakers that rates would stay high, particularly after a clutch of US regional bank failures, only for market rates to collapse shortly after the message from central banks had been absorbed.”

Besides, markets have an asymmetric tendency to overshoot its expectations when faced with signals of good news and quickly price them in (the surge in equity markets and drop in bond yields following Powell’s press conference is the latest example), even as it under-estimates negative signals. And this asymmetry is further exacerbated by the market tendency to respond even more positively in relief when an anticipated negative news does not materialise. I have blogged here on the psychology of financial markets and here on the overshooting forward guidance and good news.