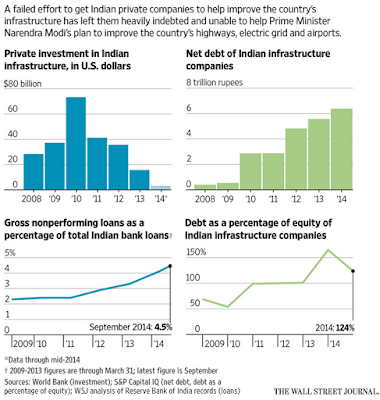

Massive infrastructure requirements, alarming decline in private infrastructure investments, rapidly growing debt burden of infrastructure companies, rising debt-to-equity ratios for projects, and rising gross non-performing assets of banks. This, captured in the WSJ graphic below, constitutes the perfect storm that the Indian economy tries to weather in its attempt to regain the high economic growth trajectory.

Despite the optimism, the ingredients for the short to medium-term just do not look promising. In fact, even if growth recovers (forget the new series), it is unlikely to be sustained for beyond 2-3 years. Household savings are declining, widening the gap between supply and demand for investment resources. In the absence of massive recapitalization, and that may not be forthcoming, bank lending is unlikely to be anywhere near sufficient to finance high growth rates.

For sustainable growth, India needs to get the ingredients right. It needs a broad enough platform of skilled labor, productive job creating industries, and consumption demand, none of which are easy to create, leave aside in a short duration. Consider each ingredient. Less than 5% of Indian workers receive some form of skill training, compared to 80% for Japan and 96% for S Korea. This compounded with the woeful school education standards means we have a 17 million strong semi-employable workforce entering the labour market each year. Less than 30% of women are employed, a distant last among any large economy. Supply of skilled labor is already a major constraint faced by businesses.

Jobs get created and broad-based economic growth sustained by the growth of formal sector small firms into medium sized ones. But India's industrial landscape is characterized by the 'missing middle', a result of firms starting small and informal and remaining so. The ease of doing business should have as much to do with improving the business environment for domestic small and medium enterprises as with large and foreign manufacturers. The former requires that the mundane issues of getting land registered, building plans approved, utility services connected, and accessing credit should become hassle-free. Unfortunately, all these run into issues of state capability.

Finally, India's consumption story too is characterized by yet another 'missing middle'. Contrary to the popular estimations of the 200-300 m strong middle class, recent domestic and foreign surveys points to a far smaller sized and not very rapidly growing middle-class. Further, rural demand, hitherto supported by the boost from various welfare programs, may no longer be able to provide the demand that supported the high growth rates of 2003-08.

China's massive investments in infrastructure were complemented with policies that promoted hundreds of thousands of town and village enterprises, rising rural incomes, well educated and skilled workforce and strong female participation in labour markets. India has none of these in place and unfortunately, there are no quick-fixes for any of these deficiencies. They require long-drawn and relentless action at multiple dimensions, especially at the level of state governments. Acknowledging the same would be a good place to start.

No comments:

Post a Comment