For some time, the Chief Economic Advisor has been pointing to corporate India’s failure to supplement the central government’s efforts to boost economic growth. The lack of dynamism in corporate India has been a recurrent theme in this blog. See this and this on the balance sheet of corporate India.

I’ll point to six ways in which corporate India is (not) contributing to broad-based and long-term high-enough economic growth. They have all been discussed on various occasions in this blog itself, and there’s compelling evidence on each.

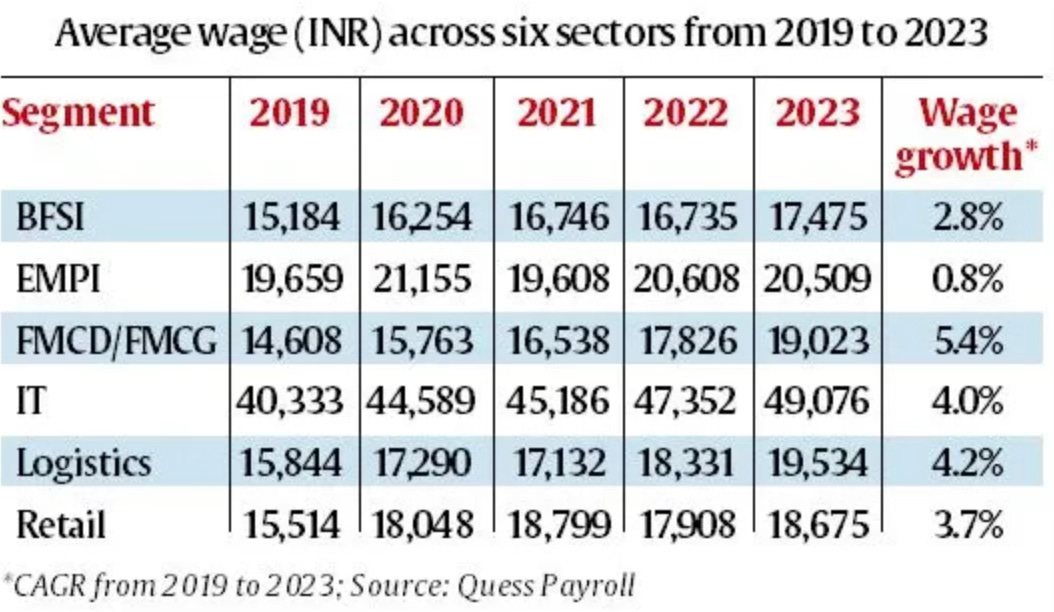

1. Wage stagnation. Even as corporate profits have been growing at a strong pace, rising four-fold in the last four years to a 15-year high (4.8% of GDP for Nifty 500 companies in 2023-24), wage growth has stagnated.

2. Jobless growth. Corporate India was already deleveraging before the pandemic. The pandemic incentivised them to automate extensively. All the while, as mentioned above, profitability continued to rise sharply. The net result was very slow job creation. As a representative sample, consider the statistics from FY24 of the top six groups of corporate India consisting of 69 listed companies employing 1.73 million people - revenues grew 7.3%, profits 22.3%, market capitalisation 43.8%, and headcount declined by -0.2%! And the trend is longer term - in the 2012-19 period, while the gross value added (GVA) grew at an annual average rate of 6.7% the employment growth rate was just 0.01%. Job creation in the manufacturing sector has been stagnant in recent years.

3. Strong preference to hire workers on a contract basis instead of regular recruitments. In the 2001-02 to 2022-23 period, while the number of workers in formal manufacturing rose from 5.96 million to 14.61 million, the share of contract workers rose from 21.8% to 40.7%.

4. Reluctance to invest, despite good profits, de-levered balance sheets, and reasonable/stable economic growth prospects. An analysis of 408 non-financial corporates who make up the BSE 500 and form 94-95% of the net fixed assets of the index companies over the 2014-24 period reveals that their share of fixed assets (as a percentage of total assets) declined from 66% to 59% and the ratio of net fixed to financial assets declined from 1.95 to 1.49.

5. Abysmally low expenditure on R&D, even by the largest companies in the knowledge sectors like pharmaceuticals and IT. Indian firms invest just 0.3% of GDP in in-house R&D, compared to a world average of 1.5%. It has just 23 firms among the global top 2500 R&D investors, whose total spending was just 4.7 billion euros, compared to 596.15 bn euros among US companies, 222.01 bn among Chinese, 116.3 bn among Japanese, 103.77 bn among German, 37.02 bn among S Korean, 35.92 bn among British, 31.66 bn among French companies.

6. A distinct preference to focus its efforts on expanding toplines through import substitution instead of export competition. This is borne out by the absence of any major consumer brands or globally competitive manufacturers from India. Public policy may have unwittingly played along by not insisting on export competition in the Production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme.

Supporters of corporate India will argue that these views are efforts by the government to deflect attention from its failings and broader factors beyond its control. They’ll point to the elephant in the room: consumption demand growth. They’ll argue that unless there’s robust aggregate demand, it’s futile, even wasteful, to throw money at the supply (or investment) side. They’ll also point to the uncertainties posed by geopolitical tensions, technology developments like Artificial Intelligence etc.

Critics’ and supporters’ claims are not mutually exclusive. Both are right. Yes, there are genuine aggregate demand concerns, but that cannot absolve corporate India of short-sightedness and unwillingness to contribute to broad-based and sustainable economic growth, especially when their balance sheets are in the pink of health.

Surprisingly, there’s such a paucity of serious research examining these trends and surfacing them for public debates. It’s also due to the dominance of a lazy ideological narrative on India’s economic growth that lays all the blame and responsibilities on the government while overlooking these important failings of the private sector. It’s time that this narrative be questioned.

No comments:

Post a Comment