Lord Keynes famously said that the equity markets are like a beauty contest. Instead of buying those stocks that you think have the best fundamentals, you buy those that others think are the best. Much the same applies to the electoral markets in democracies. And here narratives have an important role to play. And, as I blogged here, narratives can be in dissonance with reality.

France and the US are two examples. As Simon Kuper writes, the French economy is doing its best in decades, combining both economic dynamism (it has become the favoured destination for investors and a crop of tech unicorns have emerge; the unemployment rate at 7.5% is the lowest since 1982; three of the five largest EU companies are French luxury companies; it produces energy with the lowest carbon intensity of any large economy etc.) and social welfare (its social protection spending at 23.8% is the highest in the EU). Its social outcomes are far from dismal - its streets have got safer and murder rate has halved since 1993; it has the highest EU birth rate etc.

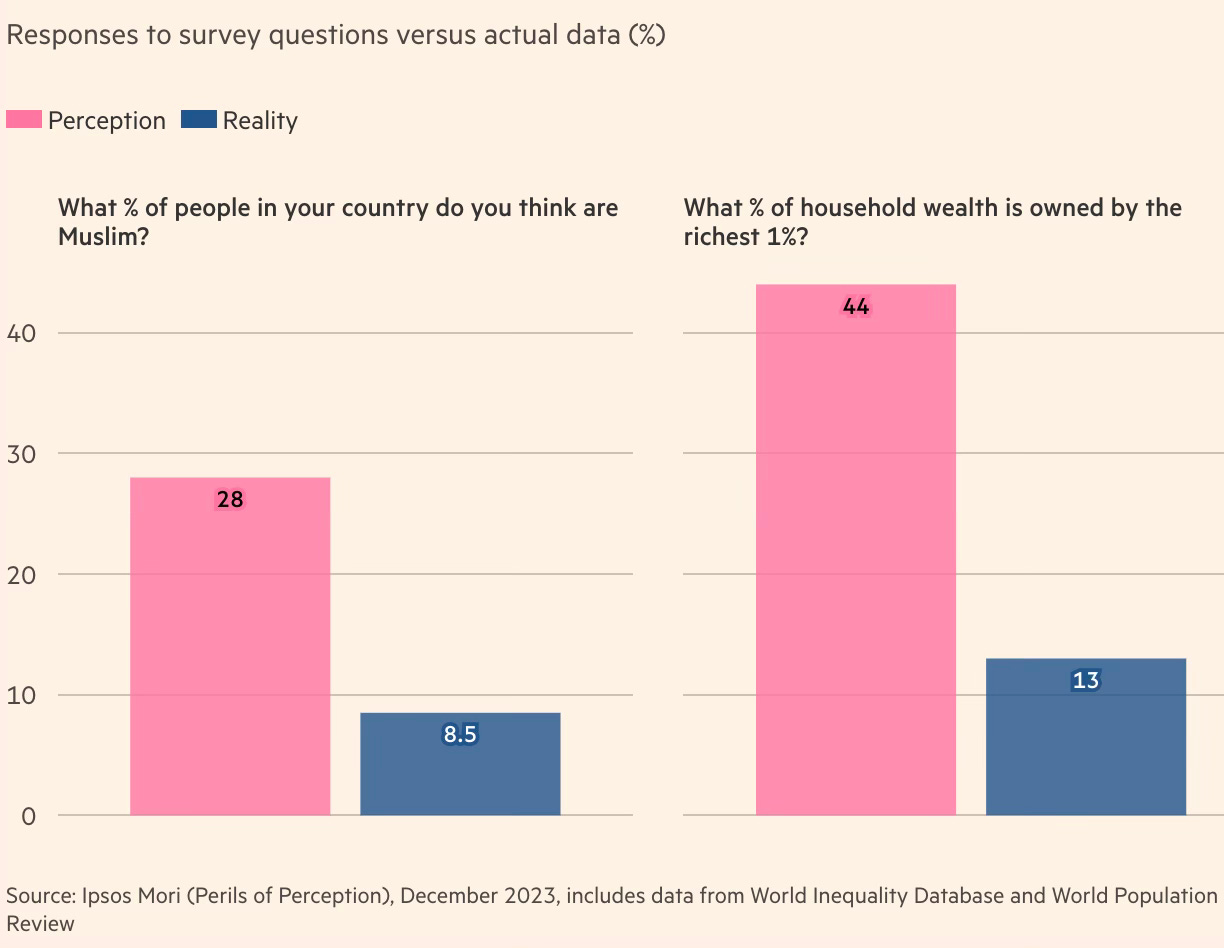

But there’s gloom everywhere. An October 2023 poll by Ipsos-Sopra Steria found that 82% of respondents agreed with the statement that “France is in decline”. Another poll in 2021 indicated that 45% of the people think the country could enter a civil war. Consider the perception-reality gap in France on certain survey questions.

The situation is the same in the US. The economy is in great shape - fastest growing advanced economy, unemployment at its lowest level in 50 years, strong wage growth, surging manufacturing investment, stock markets at their peak and showing no signs of relenting, inflation almost back to normalcy etc. It’s the best-performing major economy. But Gillian Tett points to the perception-reality gap

A Guardian-Harris survey last month shows that 56 per cent of voters think the country is in recession, 49 per cent think that the stock market has fallen this year and 49 per cent think unemployment is at record-high levels. Ouch. Unsurprisingly, that leaves only 32 per cent of voters who trust Biden to run the economy, compared to 46 per cent who trust Donald Trump, according to an Ipsos poll. This is ominous given that 88 per cent also cite the economy as the top factor influencing their votes.

The dissonance between perception and reality on the economy in the US has been described by some as a “vibecession” - a case of acute deficit of good vibes in the economy. Paul Krugman points to the findings of the US Federal Reserve’s latest annual survey of economic well being of households.

The (results of) Federal Reserve’s annual survey of economic well-being of American households… show that… most Americans continue to say that they’re doing OK financially, but they think the national economy is doing badly — while they’re being considerably more positive about their local economy… As the report notes, “the gap between people’s perceptions of their own financial well-being and their perception of the national economy has nearly doubled since 2019.”… according to the latest Quinnipiac University poll of Wisconsin, 65 percent of registered voters there say that the national economy is not so good or is poor, while the same percentage say that their own financial situation is good or excellent. Then there’s the new Harris Poll survey conducted for The Guardian. The headline is that 56 percent of Americans believe that our economy — which is adding jobs in the hundreds of thousands each month — is in a recession… What’s harder to rationalize is that roughly half of respondents believe that unemployment, which remains close to a 50-year low, is at a 50-year high or, even more startling, that stock prices — which have been hitting records, and are reported everywhere, all the time — have been falling.

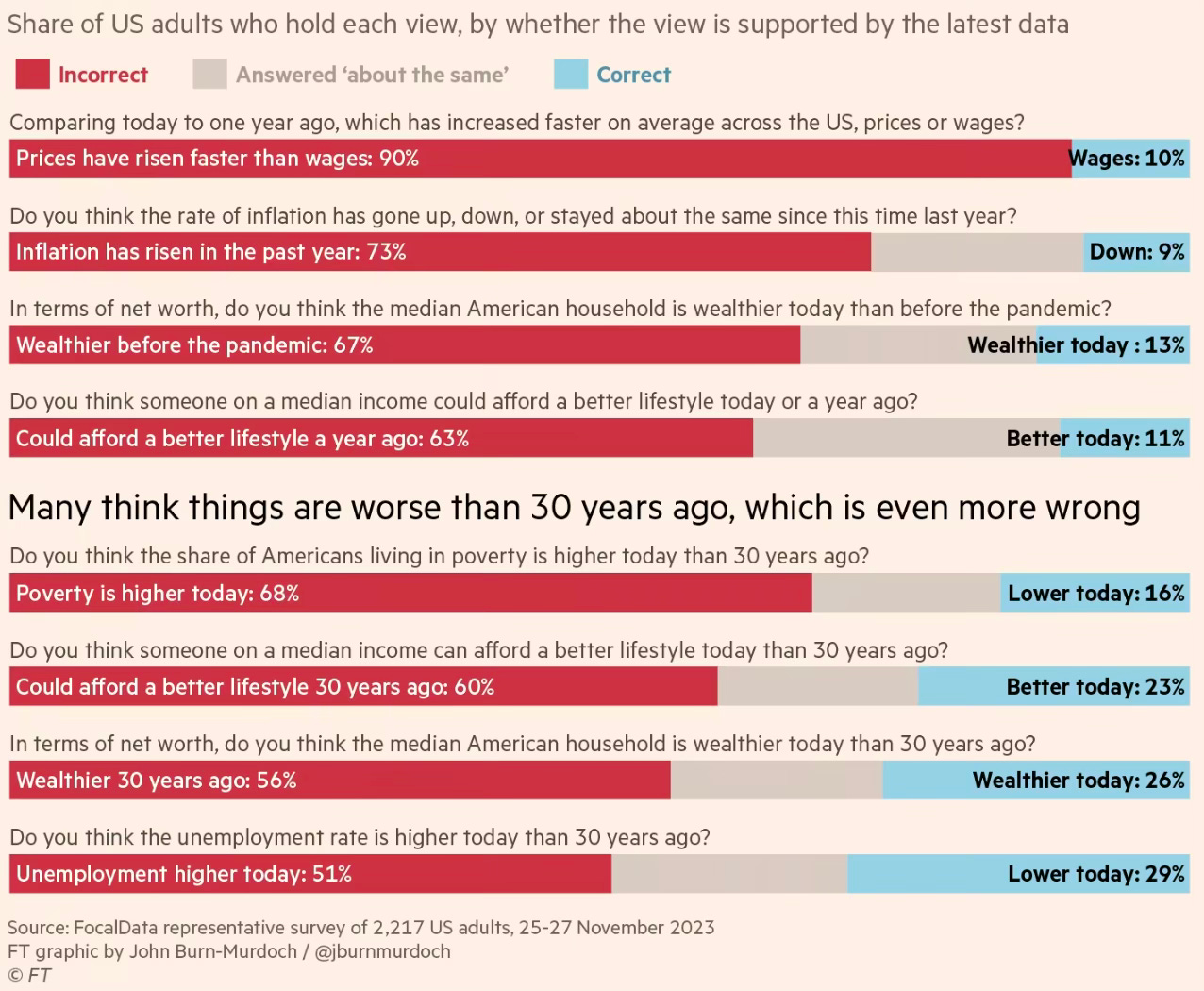

Or sample this from John Burn-Murdoch in FT,

Large majorities of Americans think the median income today pays for a worse lifestyle than 30 years ago (demonstrably false), and that poverty is higher than it was a generation ago (it has plummeted). One particularly revealing statistic is that Americans’ assessment of their own financial situation has barely budged over the past five years, but their rating of the national economy has worsened steeply. It seems they have decided that the vibes are bad, so things must be going badly for most other people, even if not for themselves… FocalData ran a poll asking a representative sample of 2,000 US adults whether they thought economic circumstances had improved or deteriorated over recent years. The results were startling: Americans are consistently wrong in the negative direction on almost every measure we polled. By huge margins, they believe inflation is still rising (it’s falling), that it has outstripped wage growth (wages have outpaced prices), and that they have become less wealthy (they’ve become much wealthier).

Americans are so wrong when they say that their economic circumstances are getting worse.

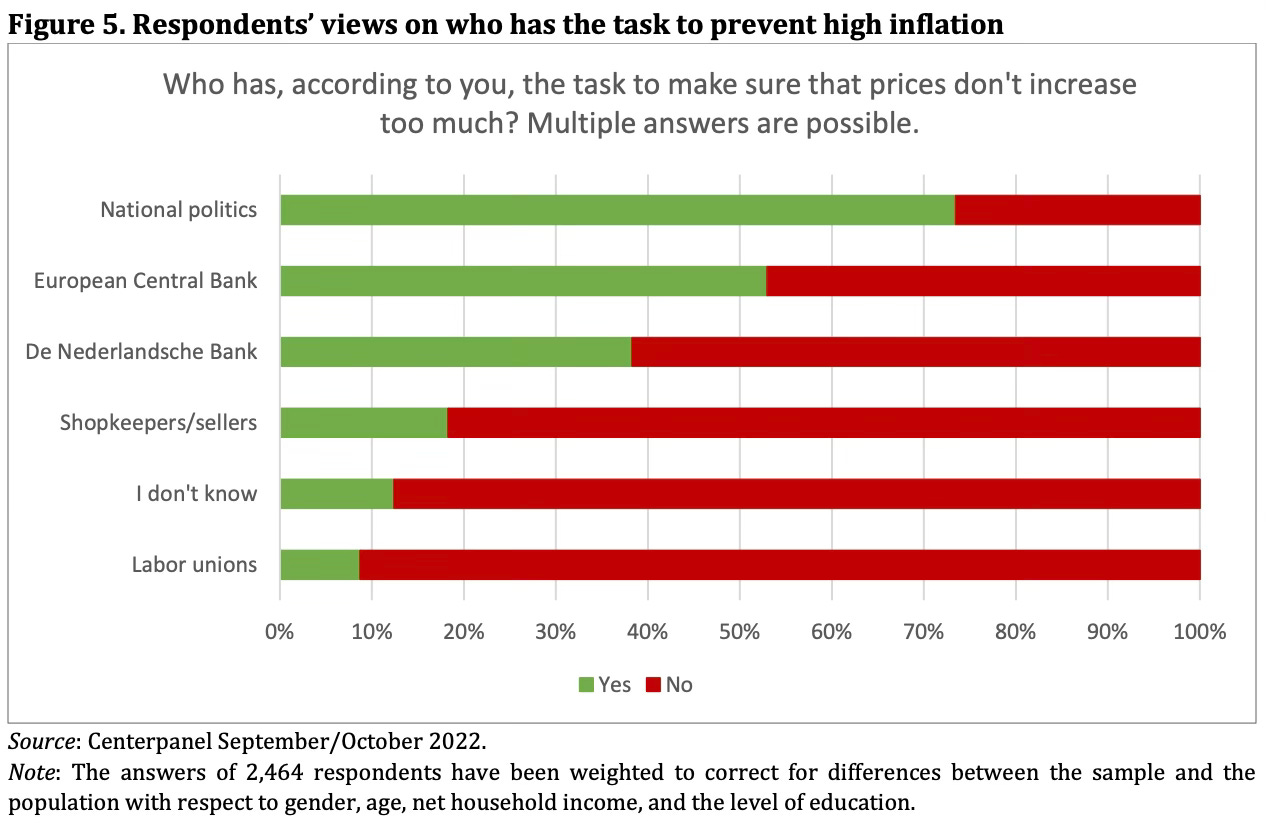

In this context, two recent papers offer some insights. The first paper by researchers at the Dutch central bank (HT: Gillian Tett) based on a survey of 2400 households point to inflation having impacts that go beyond the market to influencing people’s trust on institutions and politics.

Using a survey in the Netherlands, we find that the recent increase in inflation is associated with a decline in trust in the Dutch central bank and Dutch politics. The higher individuals’ perceived inflation is and the harder it is for them to make ends meet, the lower their trust in the European Central Bank, the Dutch central bank, and Dutch politics. We also find that people trust authorities considered responsible for bringing inflation down less. Quite remarkably, most people think government is responsible for maintaining price stability

The second paper by Joel P Flynn and Karthik Sastry point to narratives having serious real macroeconomic impacts. They examine the impact of narratives among US firms.

We study the macroeconomic implications of narratives, defined as beliefs about the economy that spread contagiously. In an otherwise standard business-cycle model, narratives generate persistent and belief-driven fluctuations. We develop a conceptual framework in which narratives form building blocks of agents’ beliefs, affect agents’ decisions, and spread contagiously and associatively between agents. We develop a narrative business-cycle model and find that narratives can generate non-fundamentally driven boom-bust cycles and hysteresis… Empirically, we use natural-language-processing methods to measure firms' narratives. Consistent with the theory, narratives spread contagiously and firms expand after adopting optimistic narratives, even though these narratives have no predictive power for future firm fundamentals. Quantitatively, narratives explain 32% and 18% of the output reductions over the early 2000s recession and Great Recession, respectively, and 19% of output variance.

Some observations:

1. Well-articulated narratives have enormous power. Such articulation requires both the packaging of the issues and also its targeting.

Sample this from Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right Rassemblement National (RN).

Le Pen depicts a France that’s in “generalised collapse”. It’s a place where acts of violence are “exploding in villages”, driven largely, she implies, by unassimilable non-white men. She warns that the country could soon descend into civil war. In a poll in 2021, 45 per cent of respondents agreed. Economically, she calls France “the world champion” of debt, unemployment and poverty. It’s a neoliberal wasteland, in which Macron has shut the factories and cruelly raised the pension age to an inhuman 64.

Since taking over RN in 2011, Le Pen has completed several image makeovers to distance the Party from its fascist roots, including the latest involving the annoinment of the 28-year old social-media darling Jordan Bardella as the RN’s prime ministerial candidate.

The project to “detoxify” the party became Le Pen’s mission. She changed its name in 2018 (from Front National), a classic marketing strategy to make voters forget the past. She had already ousted her father from the party in 2015, and expunged other radical elements, although critics say traces of its antisemitic, racist past remain. Gradually she shifted the RN’s platform to emphasise cost of living issues and play off the supposed contempt that Parisian elites have for rural areas… Le Pen and her team helped craft a narrative around Bardella, emphasising his childhood in social housing with a divorced mother who struggled to make ends meet. He has said his views were shaped by seeing the ravages of drug dealing and crime in his local area and riots that erupted in 2005 after two adolescents died during a police chase. The actual story was slightly different. Bardella’s father was a small-business owner who sent him to private Catholic schools and gave him a more bourgeois upbringing, according to a biography by Pierre-Stéphane Fort. He did not complete his studies in geography at university and has not held a private-sector job.

I think the liberal media overlooks the brilliance of Donald Trump’s packaging of himself and his ideas, and its emulation by the likes of Le Pen and Bardella. Just as large groups of the electorate identify personally with what Donald Trump says and represents, Bardella too commands similar appeal among the electorate. We may not like it, but this appeal cannot be wished away.

2. The widening of political polarisation also means that people have become boxed into insular groups where group-think prevails. No matter what the numbers say, group think has come to prevail. I blogged here on the power exercised by extremist groups (Progressive Activists and Devoted Conservatives) on different sides is immense and all-encompassing. And their conversations set the social and political agenda for everyone. The hegemony of such narratives is impervious to logical thinking and analytical reasoning. As Upton Sinclair said, “It’s difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

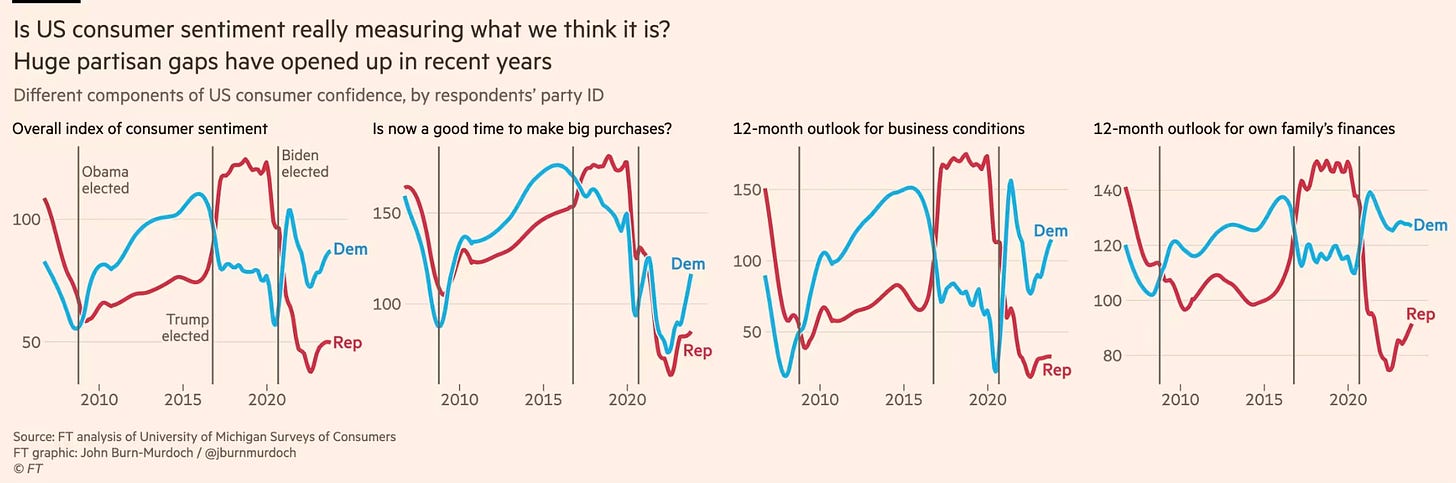

Burn-Murdoch writes in the context of the perception-reality gap in the US.

It seems US consumer sentiment is becoming the latest victim of expressive responding, where people give incorrect answers to questions to signal wider tribal political or social affiliations.

This applies across countries. Consider this

A Harvard-Harris poll shows that while 59 per cent of Democrats think that the economy is on the right track, only 13 per cent of Republicans agree. Yet they largely face the same economy.

3. Finally, there’s the issue of ideology. Or the increasing lack of it among the mainstream liberal parties. Parties with right-wing populist ideologies have assumed the centre stage on both sides of the Atlantic. This has coincided with a period over which the liberal parties have shifted to the centre in pursuit of balance between the right and left, and conservatives and liberals. This was the essence of the Third Way movement that Tony Blair initiated with the UK’s Labour Party.

Centre-left political parties like the Democrats in the US under Bill Clinton, the Labour Party in the UK under Blair, and the Socialist Party in France under Emmanuel Macron (he split the traditional left and right parties and created a new Renaissance Party of the centre) have sought to widen their electoral base by moving to the centre. From being a counter-point to their economically rightwing (capital-favouring) opponents (Republicans in the US, Conservatives in the UK, and The Republicans in France), these centrist parties sought to embrace the market while also retaining their core working class (labour) bases.

From hindsight, this move to the centre appears to have been a fatal mistake. In the delicate reconciliation of the interests of labour and capital, the latter has become dominant. The leadership and the intellectual core of these parties have become captives to the interests of the capital. In the process, the new centrist avatars have alienated their core support base in the labour. The labour base has drifted to the populist camps.

This raises an important concern about the idea of moderation. Moderation has its relevance only with respect to some reference points (the right or the left, liberal or conservative). In itself, moderation cannot be an ideology. Centrist groupings like the Third Way or Rennaissance Party cannot be the basis for political parties with a coherent message and mass appeal.

More worryingly, centrists groups often end up being captured or at least perceived as being captive of the opposite ideological group. This is a greater risk to the liberals, whose courting of capital can end up with capture by the capitalists (and therefore alienation of its core working-class base). A good illustration of this phenomenon may be the Democratic Party in the US.

1 comment:

It is important to understand the narrative effects but the material reality act as gravitational force. Interest of capital always take precedence in out society, the extent keeps varying as move through cycles. The trajectory is clear though in which direction we move

Post a Comment