I have blogged on the need for developing countries like India to be prudent with the green transition. For these countries, unlike their advanced counterparts, poverty eradication competes with climate change as an existential challenge. For a large share of the populations of these countries, the daily and immediate challenge of subsistence far overrides the more distant and diffuse challenge of climate change.

It’s easy for academicians, commentators and opinion-makers to demand a rapid green transition with ambitious decarbonisation goals. They advocate coal-based electricity generation to be phased out with renewable generation, and internal combustion engines (ICE) to be phased out with electric vehicles. And they all advocate both these transitions to happen rapidly.

But all such transitions impose prohibitive costs and there’s very little understanding of who and how these costs will be borne across different sectors. It’s important to recognise these realities and design policies accordingly.

Consider the current policy in India that pushes aggressively for the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) among four-wheelers.

Amidst the frenzied commentary and euphoria around electric vehicles and batteries, we overlook chastening emerging developments in the global EV markets. Outside of China, in the developed markets EV sales growth has been stuttering.

The Times has an article that provides a good summary of the plans of the big automobile manufacturers in the US.

In the last six months, sales of electric vehicles have slowed, and American car buyers looking to cut their fuel bill and tailpipe emissions have been flocking to hybrids. Now Toyota’s sales are booming, and the company is reporting huge profits... Toyota has introduced just two fully electric models in the United States so far, betting that its gas-electric hybrids and plug-in hybrid vehicles, which it has become known for, would remain popular and were sufficient to address climate change for now... Toyota has plans to significantly increase hybrid production and sales. A hybrid version of its Tacoma pickup is rolling out. A redesigned Camry sedan, due this spring, will be available only as a hybrid...

Mercedes-Benz, which had been hoping to phase out internal combustion models by 2030, said last month that it had pushed that goal back by at least five years. Ford has lowered production targets for electric vehicles and is slowing construction on plants that are supposed to produce batteries for electric vehicles. G.M., which had stopped selling hybrids in the United States to focus on electric vehicles, has delayed the introduction of a few battery-powered models. It is also now planning to reintroduce hybrid and plug-in hybrid models, which dealers had pushed for.

The article discusses the challenges faced by EVs.

Electric vehicles have so far failed to win over many car buyers because they are generally more expensive than combustion or hybrid models even after taking into account government incentives. The challenges of charging electric vehicles, worries about range and their performance in cold weather have also caused some people to hesitate. Hybrids don’t face many of those issues. Some hybrids cost only a few hundred dollars more than similar gasoline cars — a premium that owners can quickly recoup in fuel savings. In addition, regular hybrids never have to be plugged in.Plug-in hybrid models, some of which can travel on just electricity for more than 40 miles and have a gasoline engine for longer trips, have much smaller batteries than electric vehicles and can be recharged relatively quickly. But these vehicles, which make up a small part of the market, may not be as beneficial financially or environmentally when driven long distances on just gasoline.

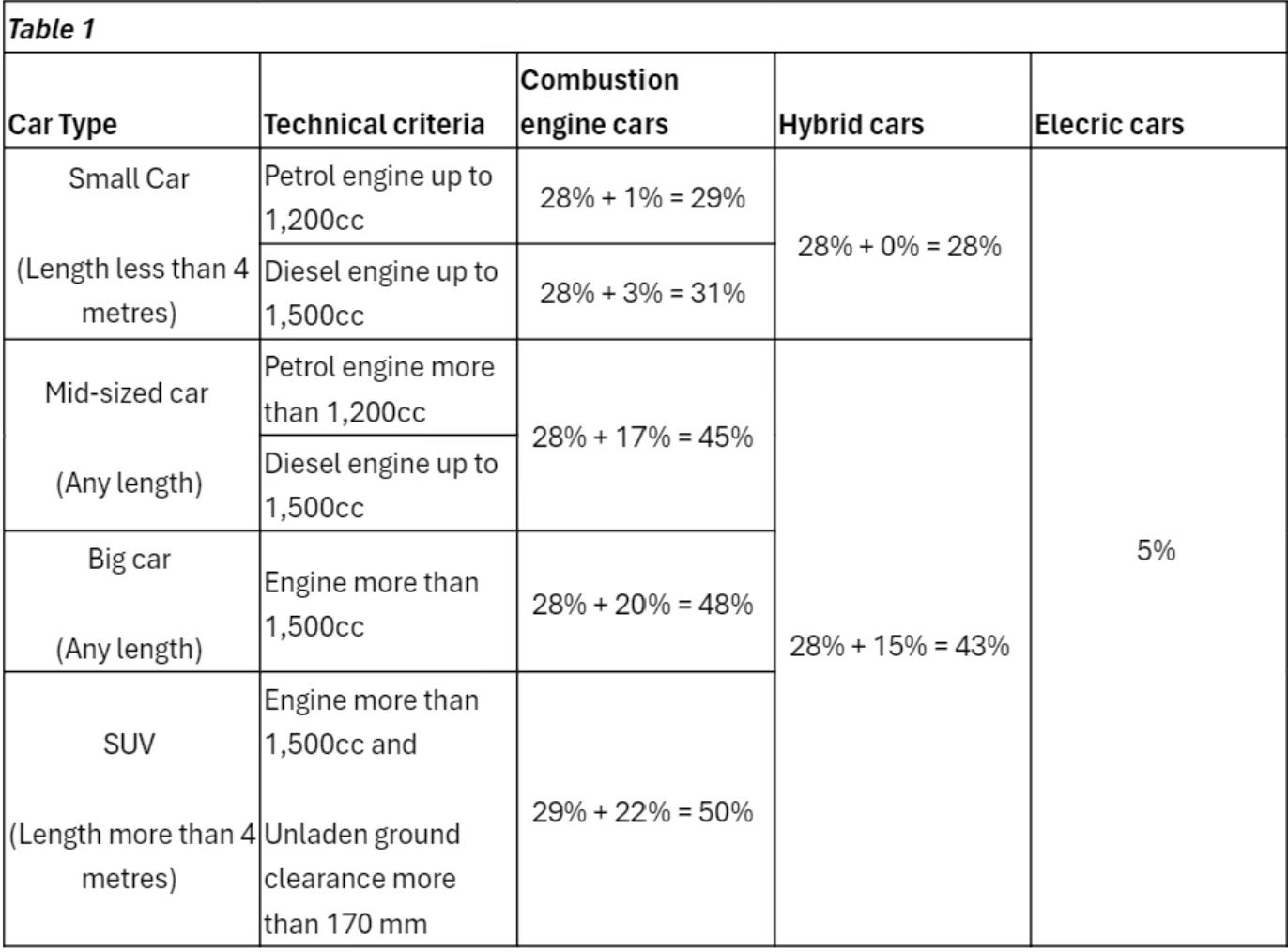

A recent Livemint article had this table on the taxes levied on various categories of four-wheelers in India.

Hybrid vehicles are taxed at the highest GST rate of 28%, the same as ICE vehicles. They are also taxed with a cess of 1-7 percentage points depending on the car type. In contrast, EVs attract a preferential GST rate of 5% with no additional cess.

The article points to the case for hybrid four-wheeler vehicles over EVs.

Pro-hybrid companies have argued that hybrid vehicles emit significantly lower emissions than combustion engine vehicles but continue to be taxed at nearly the same rate… These companies have further argued that even under best case scenario, electric cars will account for around 30% of new car sales by 2030, leaving a substantial portion of the market to combustion engines. In such a situation, tax cuts on hybrid vehicles could see higher adoption of hybrids in the non-electric car market, especially in the case of larger vehicles. Using the Maruti Suzuki Grand Vitara as an example again, the strong hybrid version boasts a fuel efficiency that is over 33% better than its mild hybrid variant. It’s claimed fuel economy is as much as 50% better than comparable rivals with conventional powertrains.

It’s clear that public policy in India has made the decisive choice in leapfrogging from ICE to EVs in four-wheelers. There’s no space for hybrids and plug-in hybrids in the government’s policy priorities.

Given that meaningful reductions in emissions are an immediate necessity, is the direct shift from ICE to EVs the most practical strategy for India? Is the direct transition even possible given the local demand conditions? What’s the opportunity cost of overlooking the phased transition from ICE to EVs through full hybrids and plug-in hybrids? Have we examined the strategic considerations involved in the choice made, especially important given the global dependence on China for battery inputs and batteries themselves? What could be an alternative EV strategy for India?

A few thoughts in this context:

1. I’m not sure whether the Indian market can support the demand for anything more than a few lakh EVs for the foreseeable future. The domestic production in 2022 was 49,800 out of 3.8 million four-wheelers and is currently about 7000-8000 per month. Imports are anyways more expensive. Even at the most optimistic growth forecasts, four-wheeler EVs are unlikely to take up more than 10% of the market share this decade. Therefore a policy that directly targets EVs while also discouraging hybrids runs the risk of foregoing the considerable immediate carbon emissions reductions possible from the far more affordable and competitive hybrids.

2. Then there’s the question of whether the urban Indian four-wheeler market needs EVs. Given the short urban commute requirements, hybrids and plug-in hybrids more than serve the purpose. When less is enough why do more, and that too at a prohibitive cost?

3. Given the universal trend of EVs co-existing with different kinds of hybrids and the near certainty of ICE vehicles retaining a major share of the market for four-wheelers, India will not only not miss out on any global trend but would, in fact, be going with the global norm.

4. Unlike EVs, hybrids of both kinds require smaller batteries. The battery chemistry too is less daunting. This means far less dependence on China for batteries and its inputs, with all the strategic and national security benefits. It also means a much greater likelihood of Indian battery manufacturers being able to acquire a foothold in the global battery value chain.

5. One of the important motivators for EV adoption in India is also the Chinese strategy of plunging headlong into EVs across market segments. Like with most other areas, the Chinese policies to encourage EV adoption are extremely wasteful and motivated by larger macroeconomic imperatives of the regime in Beijing to find new drivers of economic growth to replace weakening engines of growth. India would do well to avoid being sucked into following what China is doing.

6. On the EV side, instead of four-wheelers, India’s public policy should instead aggressively double down on two and three-wheelers. It’s far more likely that EVs will become the dominant part of these markets shortly. It’s more realistic to expect public policy to expedite that transition. Further, acquiring expertise in two and three-wheeler EVs will provide the manufacturing base and technology expertise to move more credibly into the affordable four-wheeler EV market.

7. On a prudent note too it makes sense for India to adopt a cautious wait-and-watch policy with EVs. The EV market is a rapidly changing landscape due to battery and car technology evolution. Then there’s the geo-political uncertainty of sourcing critical minerals for EV batteries. From all evidence, it appears that we are some time away from the arrival of the truly affordable EV that the Indian market requires.

Therefore, instead of expending scarce public finance and policy efforts on four-wheeler EVs, India should prioritise two- and three-wheeler EVs and hybrid variants of four-wheelers while also keeping its eye open to engage opportunistically on four-wheeler EVs. This would help the country acquire strong domestic manufacturing capabilities in EVs and batteries, apart from achieving significant immediate reductions in carbon emissions. It would be both sound environmental policy and sound economics.

8. Finally, the focus on EVs should not blind us to alternative transition fuels like natural gas. After all, one of the most successful examples of carbon emission reduction in the transportation sector in the country has been the adoption of CNG in public transport buses in the National Capital Region of Delhi.

Much the same logic of phasing transitions applies to the shift from thermal to renewable power generation. Instead of trying to abandon fossil-fuel power altogether, public policy should incentivise existing thermal plants to enhance their energy efficiencies and lower emissions by improving operations and retrofitting. Policy should also encourage the use of natural gas in the transition period.

No comments:

Post a Comment