The US Department of Justice’s suit against Google outlines with great clarity how Google has positioned itself across the full value chain of internet advertising and systematically abuses its market dominance.

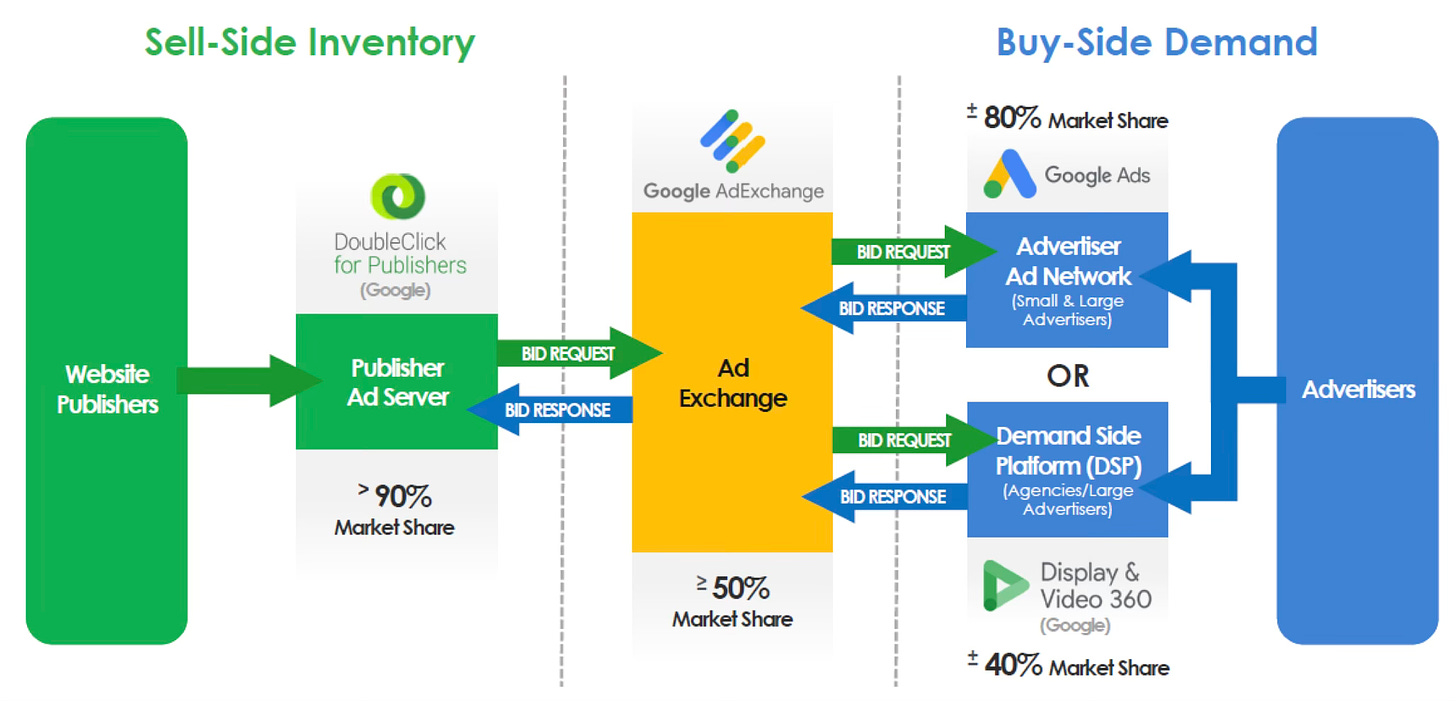

Every time an internet user opens a webpage with ad space to sell, ad tech tools almost instantly match that website publisher with an advertiser looking to promote its products or services to the website’s individual user. This process typically involves the use of an automated advertising exchange that runs a high-speed auction designed to identify the best match between a publisher selling internet ad space and the advertisers looking to buy it... One industry behemoth, Google, has corrupted legitimate competition in the ad tech industry by engaging in a systematic campaign to seize control of the wide swath of high-tech tools used by publishers, advertisers, and brokers, to facilitate digital advertising. Having inserted itself into all aspects of the digital advertising marketplace, Google has used anticompetitive, exclusionary, and unlawful means to eliminate or severely diminish any threat to its dominance over digital advertising technologies.

Google’s plan has been simple but effective: (1) neutralize or eliminate ad tech competitors, actual or potential, through a series of acquisitions; and (2) wield its dominance across digital advertising markets to force more publishers and advertisers to use its products while disrupting their ability to use competing products effectively... Google, a single company with pervasive conflicts of interest, now controls: (1) the technology used by nearly every major website publisher to offer advertising space for sale; (2) the leading tools used by advertisers to buy that advertising space; and (3) the largest ad exchange that matches publishers with advertisers each time that ad space is sold. Google’s pervasive power over the entire ad tech industry has been questioned by its own digital advertising executives, at least one of whom aptly begged the question: “[I]s there a deeper issue with us owning the platform, the exchange, and a huge network? The analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.”

By deploying opaque rules that benefit itself and harm rivals, Google has wielded its power across the ad tech industry to dictate how digital advertising is sold, and the very terms on which its rivals can compete. Google abuses its monopoly power to disadvantage website publishers and advertisers who dare to use competing ad tech products in a search for higher quality, or lower cost, matches. Google uses its dominion over digital advertising technology to funnel more transactions to its own ad tech products where it extracts inflated fees to line its own pockets at the expense of the advertisers and publishers it purportedly serves…

The harm is clear: website creators earn less, and advertisers pay more, than they would in a market where unfettered competitive pressure could discipline prices and lead to more innovative ad tech tools that would ultimately result in higher quality and lower cost transactions for market participants. And this conduct hurts all of us because, as publishers make less money from advertisements, fewer publishers are able to offer internet content without subscriptions, paywalls, or alternative forms of monetization. One troubling, but revealing, statistic demonstrates the point: on average, Google keeps at least thirty cents—and sometimes far more—of each advertising dollar flowing from advertisers to website publishers through Google’s ad tech tools. Google’s own internal documents concede that Google would earn far less in a competitive market.

This problem is not unique to digital technologies. Instead, it’s a common problem with all platforms or platform marketplaces. They are as old as markets and most markets are platforms. Shops, malls, roads, railways, utilities etc are all platforms. Even a school or college, clinic or hospital is also a platform. Imagine a highway monopolist dominating the markets for toll-gate operations, highway rest areas, vehicle manufacturing, ride-sharing, and so on.

All these are universally used markets, enjoy monopoly features, and benefit from network effects (more users result in greater value from its use). Besides, most often they are privately owned, thereby have monopolistic exploitation incentives. They are classic market failures. Therefore the case for their regulation.

As illustrations, consider the following. Walmart charges exorbitant fees from retail brands to display their wares on its shelves. A railway or road concessionaire charges high fees for railway lines or vehicles to use the infrastructure. A utility company charges high wheeling tariffs on electricity providers using its infrastructure. And so on. And to top it off, all these monopolists also have their proprietary products and services that can potentially get preferential treatment to use the market platform.

The fundamental issue here is that of the near monopoly or disproportionate market power that many platforms command. These platforms become gatekeepers to market access. It becomes a problem when the platform is privately owned and the platform owner starts to charge exorbitant platform access fees. This is considered a market failure. Therefore, given this pervasive problem with all privately owned platforms, such markets are regulated.

In the initial stages of the emergence of any innovation, it’s natural for the first movers to be incentivised with a high premium in their returns. For practical reasons, the regulations too take time to emerge. All the aforementioned historical platform markets too followed this trajectory of development. We know of the market abuse problems associated with railroad monopolies which made billionaires out of their owners in the US. We also know about the fierce opposition from entrenched monopolists to regulating these markets.

The evolution of internet-based platforms too is following the same path. Given their practices, profit margins, and piles of cash surpluses, it’s clear that the monopolists have been allowed to enjoy an extended period of unregulated over-exploitation. In any case, it’s hard to argue that e-commerce or social media or payment platforms are not mature enough and therefore need more innovation runway before they are regulated. They should have been regulated yesterday.

The elite capture of the intelligentsia and academia has meant that the commentary and thinking on this issue have been muted or confined to tinkering at the margins. The political capture of the rule-making process has been critical to perpetuating the unregulated over-exploitation of these markets. It’s a testament to the failure of the progressive movement that they have been co-opted by the Big Tech and Wall Street interests.

In the US, the courts are still beholden to the consumer welfare test for digital market regulation and thereby tend to overlook the market abuse and anti-competitive practices that Big Tech firms indulge in. In this context, the EU’s ongoing actions against the technology firms deserve to be strongly supported. The centrepiece of the EU’s anti-trust pursuit is the European Union's Digital Markets Act.

Its full implementation has opened the possibility of widespread anti-competitive actions by the EU. A major objective of the Act is to prevent large tech companies from abusing their market dominance to crush competition and build monopolies. The DMA Rules which came into effect in March 2022 had given time to the large systemic companies (defined appropriately as "gatekeepers") two years till March 7, 2024, for compliance.

The FT has a long read on the impact of the DMA Rules

There is little evidence yet to suggest that the law is having the desired effect. Industry groups representing travel apps such as Airbnb and Booking.com, and entertainment apps like Spotify and Deezer, complain the tech companies are focused on the letter of the law rather than the spirit of it, and it is having no meaningful impact on their businesses. Judging by the record stock market highs enjoyed by some of these companies, Wall Street doesn’t believe it will have much practical effect on profits or the level of competition either — particularly as the tech industry hurtles into the AI age, resetting the competitive dynamics in some of the core tech markets... The big companies have been adept in the past at redesigning their services to sidestep regulations, making it very difficult for under-resourced government agencies to keep up, this investor says. The law does grant European regulators extraordinary powers of enforcement, including fines of up to 20 per cent of total worldwide annual turnover for repeat infringements, or — as a “last resort option”, forced structural changes such as the break-up of businesses...A gatekeeper is defined by the law as a platform with an annual turnover of more than €7.5bn, a market cap above €75bn and active monthly users in the EU of 45mn. The commission has singled out 22 “core platform services” offered by the six, ranging from Google’s search engine and Meta’s Facebook and Instagram services to Apple’s App Store. The law forbids the tech companies giving favourable treatment to their in-house services at the expense of third parties — a practice known as self-preferencing — and obliges them to open up their platforms to more alternative services, presenting users with more choices. It also challenges their power to share data between their own services — between Facebook and WhatsApp, for example — without their users’ consent, and seeks to make it easier to switch by making it simpler for users to export their data. “The gatekeeper theory of industry domination is profound,” says Megan Gray, formerly a US Federal Trade Commission lawyer and general counsel at search company DuckDuckGo. At least in theory, it gives the regulators a powerful weapon, she says. On paper, the law could have a direct impact on the profitability of some important tech services, says Gallant. “The DMA poses some risk to Apple’s App Store commissions, which is the biggest part of their services business,” he says.

But the market participants feel that the technology companies will figure out ways to subvert the DMA Rules.

According to Gray, the entrenched nature of the dominant platforms, and in particular the tight linkages between their services that have turned them into powerful digital “ecosystems”, will make it hard to pick them apart by attacking individual products or services. The most drastic effects of the new regulations are also likely to be blunted by the manner in which the tech companies have said they will adapt their services to comply with the DMA... Tech companies are also implementing changes in ways that allow them to hold on to their competitive advantage. This year, Apple published a highly detailed set of technical changes that in effect open the way for rival app stores on the iPhone and iPad, while also allowing developers to stop using its payments service. But it also said that anyone choosing to take advantage of these new arrangements would have to pay a new fee of €0.50 cent for every app downloaded over 1 million installations — something that would hit companies that have large numbers of free app users on mobile platforms, making them less likely to take advantage of the new freedom to launch an app store of their own...

“Spotify, like so many other developers, now faces an untenable situation,” it said following Apple’s announcement. “Under the new terms, if we stay in the App Store and want to offer our own in-app payment, we will pay a 17 per cent commission and a €0.50 cent core technology fee per install and year. This equates for us to being the same or worse as under the old rules.” The changes were designed to give developers like Spotify choice, Apple said. “Every developer can choose to stay on the same terms in place today,” it said, “and under the new terms, more than 99 per cent of developers would pay the same or less to Apple.” The tech companies have also limited most of their technical changes to users in the EU, rather than extending them worldwide — limiting the likelihood of their wider adoption, and creating obstacles for developers.

In India, a Digital Competition Bill is under preparation. A news report says,

The proposed Digital Competition Bill is expected to put a self-reporting obligation on online entities to declare their dealings are fair and transparent, not restrictive towards third-party applications, according to sources in the know. The digital entities that qualify as gatekeeper platforms or systemically important digital intermediaries (SIDIs) would have to provide this declaration to the Competition Commission of India (CCI), according to the proposed Bill. The CCI will have the power to levy a fine of up to 1 per cent of the global turnover of the online entity in case it fails to make this declaration, sources said.

Such online firms would have six months to submit this declaration from the time they cross the threshold set for SIDIs, it is learnt. These thresholds, according to sources, are based on the India and global turnover of online platforms, their gross merchandise value in India, average global market capitalisation, and the number of end users. As part of the self-reporting obligation, SIDIs would have to declare that they are not inter-mixing or cross-mixing personal data of end users without their consent and have kept anti-steering provisions, which stop users from going out to other platforms, in check.

On the issue of digital market regulation, Rana Faroohar writes about the divergence between how consumers and regulators view dynamic pricing in physical and digital markets.

Surge pricing is something that anyone who takes a ride share on a regular basis has become used to. Try calling an Uber or Lyft on a rainy day during the dinner hour or around the school pick-up or drop-off time and you’ll be paying more than your usual rate — sometimes a lot more. Yet when consumers are confronted with common online business models like “dynamic pricing” in the bricks-and-mortar world, they may revolt… Platform technology firms developed or perfected techniques like dynamic pricing, real-time auctions, data tracking, preferential advertising and all the other tricks of surveillance capitalism. But the behaviour we take for granted online somehow becomes more problematic when these methods are deployed in the real world. People are outraged about the price of burgers or their rent surging but don’t think twice when it happens to the cost of their commute — particularly when they are booking it on an app…

I’d love to see the FTC, for example, use its rulemaking power to stipulate a “thou shalt not discriminate” statue that makes it illegal to charge people different prices for different goods, no matter how and where they are buying them. What’s illegal in the physical world should also be illegal in the online world. This would put the onus on companies to prove that they are not causing harm, rather than forcing regulators to create a distinct and more complex system for a particular industry. Online or offline, all businesses should be playing by the same rules.

I have blogged earlier about the unfair regulatory arbitrage that digital market firms exploit to their advantage. There’s no reason why such regulatory arbitrage should be allowed to continue in mature marketplaces.

Big Tech will respond to digital market regulation with denial, tinkering, obfuscation, and brazenness. Unless dealt with firmness, they will keep figuring out ways to limit conceding ground by getting around regulation. Fines are too small in relative terms and are already internalised as a cost of doing business. Aggressive enforcement will have to become the norm. This will require often exorbitant or disproportionate fines, even at the risk of judicial reversals. It will also require the “nuclear option” of even breaking up firms. The norms can be upended and new norms established only through such aggressive actions. When the pendulum has swung too far to one side, there’s a need for disproportionate force from the other side.

However such actions will require political will and popular support to force these changes in a meaningful manner on the entrenched technology firms.

For references on earlier posts, here is a compilation. I have compared the likes of Amazon to "a large vehicle manufacturer having the power to both prohibit someone from using the road and also make competing vehicle manufacturers unattractive (say, because of inadequate servicing options) for users". I have blogged earlier here(beginning of anti-trust actions in the US and Europe), here (Google and anti-trust challenge), here (anti-trust challenge in the US), here (market monopolisation), and here (Amazon's market abuse of startups) on the problems with market concentration and the need for regulation. This points to what Google founders themselves thought about data monetisation and digital advertising. I have blogged here, here, and here on the problems with regulatory arbitrage and here on the market service quality problems due to limited and poor regulation. And we are not even talking about the several other distortions arising from such market concentration, especially the valuation bubbles in the financial markets - see this and this. Finally, this is a summary examining the dynamics of digital markets and how it offer a different perspective on these markets, and this is a summary of how the big technology companies have become digital gatekeepers to large and critical markets.

No comments:

Post a Comment