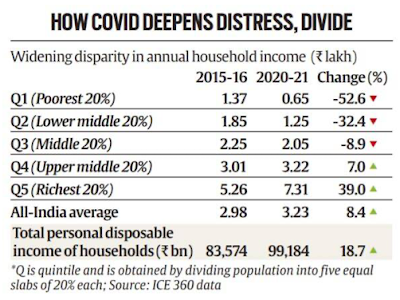

The annual income of the poorest 20% of Indian households, constantly rising since 1995, plunged 53% in the pandemic year 2020-21 from their levels in 2015-16. In the same five-year period, the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39%... The survey, between April and October 2021, covered 200,000 households in the first round and 42,000 households in the second round. It was spread over 120 towns and 800 villages across 100 districts... How disruptive this distress has been for those at the bottom of the pyramid is reinforced by the fact that in the previous 11-year period between 2005 and 2016, while the household income of the richest 20% grew by 34%, the poorest 20% saw their household income surge by 183% at an average annual growth rate of 9.9%...

The survey showed that while the richest 20% accounted for 50.2% of the total household income in 1995, their share has jumped to 56.3% in 2021. On the other hand, the share of the poorest 20% dropped from 5.9% to 3.3% in the same period... While 90 per cent of the poorest 20 per cent in 2016, lived in rural India, that number had dropped to 70 per cent in 2021. On the other hand the share of poorest 20 per cent in urban areas has gone up from around 10 per cent to 30 per cent now.

The share of poor belonging to urban areas increased, reflecting the likely greater impact of the pandemic on migrants and those living in slums.

3. More on slow recovery in private sector capex in India. A Business Standard analysis of the 500 most valuable companies by market capitalisation compared the performance of the top 5% and bottom 5% on a host of indicators. On gross block (all assets owned by the company)

On allocations going into investments

And on sales growth

4. The spectacular explosion in smart phone usage time in the US, which rose from 3% of waking hours to one-third over the last decade!

Will be pretty much the same elsewhere.

5. John Hussman points to the growing dissonance between the Federal Funds rate and objective functions of monetary policy like the Taylor Rule and various real economy variables.

The Fed lowered rates to the “zero bound” for the first time during the financial crisis of 2008. It was part of a great experiment, an effort to rescue the shaken financial system and the sinking economy when Ben S. Bernanke was chair. But the experiment never really ended. Because the economy remained weak, the Fed didn’t begin raising rates until December 2015, and it never got far. By 2019, when Mr. Powell was chair, the Fed funds rate had reached only 2.50 percent before signs of economic weakness made the Fed stop. In March 2020, it fell back to nearly zero. By contrast, the Fed funds rate was as high as 6.60 percent as recently as July 2000...The amounts involved in the Fed’s quantitative easing have been staggering. Back in 2008, the Fed’s balance sheet had assets of $820 billion. They reached $4.5 trillion — yes, trillion — in 2015 and dropped only as low as $3.76 trillion in the summer of 2019. With the coronavirus financial crisis, they have ballooned again, to $8.9 trillion, and may swell a bit more before the spigot shuts. Assets held by the Fed are already more than 10 times their size in 2008, and bigger, as a proportion of gross domestic product, than at any time since World War II. The Fed’s monetary stimulus accompanied a total of roughly $5 trillion in pandemic fiscal relief by the federal government.

This is the challenge with monetary policy adjustment,

Calibrating the combined effects of quantitative tightening and interest rate increases in real time is exceedingly difficult. Cut off stimulus too rapidly and the Fed could further unnerve financial markets. It could conceivably cause a spike in unemployment and a sharp slowdown in growth, plunging the United States into a recession. Move too gingerly, on the other hand, and the Fed could allow elevated inflation expectations to become embedded, making high inflation even more damaging.

7. A good NYT piece on the dilemma facing consumer brands in associating with China and the forthcoming Winter Olympics.

“The space to please both sides has evaporated,” said Jude Blanchette, a scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “When choosing who to upset, it’s either a bad week or two of press in the U.S. versus a very real and justified fear that you’ll lose market access in China.”... the issue of human rights violations in China has not generated enough protests to threaten the profits of multinational companies, while the angry Chinese consumers have fueled painful boycotts... “If any other government in the world did what the Chinese are doing in Xinjiang or even in Hong Kong, a lot of companies would just pull up stakes,” said Michael Posner, a former State Department official who is now at New York University’s Stern School of Business. He cited decisions by companies to divest in places like Myanmar and Ethiopia, as well as the campaigns to boycott South Africa when its apartheid government sent all-white teams to the Olympics. “China is an exception,” he said. “It’s just so big, both as a market and a manufacturing juggernaut, that companies feel they can’t afford to get in the cross hairs of the government, so they just keep their mouths shut.”

8. Interesting graphic about economic recovery in the US

Inflation-adjusted output last quarter was just 1 percent below where it would have been if the pandemic had never happened. Here’s another one: Ignoring inflation, output is 1.7 percent above where it would have been absent the coronavirus.

9. The Kerala government is planning a semi-high speed railway corridor, Silverline, planned across the length of Kerala. The Rs 63,940 Cr project to be financed through external loans would cut the travel time for the 530 km commute from Trivandrum to Kasargode from 12 to 4 hours. Indian Express has an article that points to the public opposition being faced by the project.

I had blogged earlier here about the value of such a project given the urban continuum nature of the state's demography and topography. However, it remains to be seen from the financials about how sustainable it will be.

10. The bad bank is finally off the ground with the decision to transfer Rs 50,335 Cr from 15 accounts to the National Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd (NARCL) by March 31, 2022. Its private sector owned twin, India Debt Resolution Company Ltd (IDRCL) will be responsible for the resolution of the debts. NARCL will be majority owned by public sector banks and IDRCL majority owned by private sector banks. This is a good primer.

The NARCL will purchase these bad loans through a 15:85 structure, where it will pay 15 per cent of the sale consideration in cash and issue security receipts (SRs) for the remaining 85 per cent. The SRs will be guaranteed by the government. The government guarantee will essentially cover the gap between the face value of the security receipts and realised value of the assets when eventually sold to the prospective buyers. The government approved a 5-year guarantee of up to Rs 30,600 crore for security receipts to be issued by NARCL as non-cash consideration on the transfer of NPAs. This will address banks/RBI concerns about incremental provisioning. Government guarantee, valid for five years, helps in improving the value of security receipts, their liquidity and tradability. A form of contingent liability, the guarantee does not involve any immediate cash outgo for the central government.

No comments:

Post a Comment