Substack

Monday, January 31, 2022

Market failures and political economy distortions in infrastructure sector

Sunday, January 30, 2022

Weekend reading links

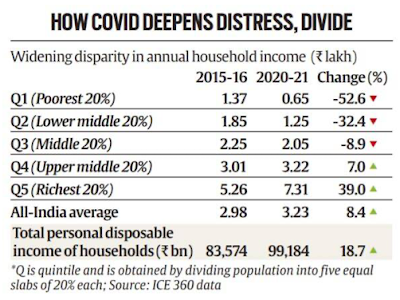

The annual income of the poorest 20% of Indian households, constantly rising since 1995, plunged 53% in the pandemic year 2020-21 from their levels in 2015-16. In the same five-year period, the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39%... The survey, between April and October 2021, covered 200,000 households in the first round and 42,000 households in the second round. It was spread over 120 towns and 800 villages across 100 districts... How disruptive this distress has been for those at the bottom of the pyramid is reinforced by the fact that in the previous 11-year period between 2005 and 2016, while the household income of the richest 20% grew by 34%, the poorest 20% saw their household income surge by 183% at an average annual growth rate of 9.9%...

The survey showed that while the richest 20% accounted for 50.2% of the total household income in 1995, their share has jumped to 56.3% in 2021. On the other hand, the share of the poorest 20% dropped from 5.9% to 3.3% in the same period... While 90 per cent of the poorest 20 per cent in 2016, lived in rural India, that number had dropped to 70 per cent in 2021. On the other hand the share of poorest 20 per cent in urban areas has gone up from around 10 per cent to 30 per cent now.

The share of poor belonging to urban areas increased, reflecting the likely greater impact of the pandemic on migrants and those living in slums.

3. More on slow recovery in private sector capex in India. A Business Standard analysis of the 500 most valuable companies by market capitalisation compared the performance of the top 5% and bottom 5% on a host of indicators. On gross block (all assets owned by the company)

On allocations going into investments

And on sales growth

4. The spectacular explosion in smart phone usage time in the US, which rose from 3% of waking hours to one-third over the last decade!

Will be pretty much the same elsewhere.

5. John Hussman points to the growing dissonance between the Federal Funds rate and objective functions of monetary policy like the Taylor Rule and various real economy variables.

The Fed lowered rates to the “zero bound” for the first time during the financial crisis of 2008. It was part of a great experiment, an effort to rescue the shaken financial system and the sinking economy when Ben S. Bernanke was chair. But the experiment never really ended. Because the economy remained weak, the Fed didn’t begin raising rates until December 2015, and it never got far. By 2019, when Mr. Powell was chair, the Fed funds rate had reached only 2.50 percent before signs of economic weakness made the Fed stop. In March 2020, it fell back to nearly zero. By contrast, the Fed funds rate was as high as 6.60 percent as recently as July 2000...The amounts involved in the Fed’s quantitative easing have been staggering. Back in 2008, the Fed’s balance sheet had assets of $820 billion. They reached $4.5 trillion — yes, trillion — in 2015 and dropped only as low as $3.76 trillion in the summer of 2019. With the coronavirus financial crisis, they have ballooned again, to $8.9 trillion, and may swell a bit more before the spigot shuts. Assets held by the Fed are already more than 10 times their size in 2008, and bigger, as a proportion of gross domestic product, than at any time since World War II. The Fed’s monetary stimulus accompanied a total of roughly $5 trillion in pandemic fiscal relief by the federal government.

This is the challenge with monetary policy adjustment,

Calibrating the combined effects of quantitative tightening and interest rate increases in real time is exceedingly difficult. Cut off stimulus too rapidly and the Fed could further unnerve financial markets. It could conceivably cause a spike in unemployment and a sharp slowdown in growth, plunging the United States into a recession. Move too gingerly, on the other hand, and the Fed could allow elevated inflation expectations to become embedded, making high inflation even more damaging.

7. A good NYT piece on the dilemma facing consumer brands in associating with China and the forthcoming Winter Olympics.

“The space to please both sides has evaporated,” said Jude Blanchette, a scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “When choosing who to upset, it’s either a bad week or two of press in the U.S. versus a very real and justified fear that you’ll lose market access in China.”... the issue of human rights violations in China has not generated enough protests to threaten the profits of multinational companies, while the angry Chinese consumers have fueled painful boycotts... “If any other government in the world did what the Chinese are doing in Xinjiang or even in Hong Kong, a lot of companies would just pull up stakes,” said Michael Posner, a former State Department official who is now at New York University’s Stern School of Business. He cited decisions by companies to divest in places like Myanmar and Ethiopia, as well as the campaigns to boycott South Africa when its apartheid government sent all-white teams to the Olympics. “China is an exception,” he said. “It’s just so big, both as a market and a manufacturing juggernaut, that companies feel they can’t afford to get in the cross hairs of the government, so they just keep their mouths shut.”

8. Interesting graphic about economic recovery in the US

Inflation-adjusted output last quarter was just 1 percent below where it would have been if the pandemic had never happened. Here’s another one: Ignoring inflation, output is 1.7 percent above where it would have been absent the coronavirus.

9. The Kerala government is planning a semi-high speed railway corridor, Silverline, planned across the length of Kerala. The Rs 63,940 Cr project to be financed through external loans would cut the travel time for the 530 km commute from Trivandrum to Kasargode from 12 to 4 hours. Indian Express has an article that points to the public opposition being faced by the project.

I had blogged earlier here about the value of such a project given the urban continuum nature of the state's demography and topography. However, it remains to be seen from the financials about how sustainable it will be.

10. The bad bank is finally off the ground with the decision to transfer Rs 50,335 Cr from 15 accounts to the National Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd (NARCL) by March 31, 2022. Its private sector owned twin, India Debt Resolution Company Ltd (IDRCL) will be responsible for the resolution of the debts. NARCL will be majority owned by public sector banks and IDRCL majority owned by private sector banks. This is a good primer.

The NARCL will purchase these bad loans through a 15:85 structure, where it will pay 15 per cent of the sale consideration in cash and issue security receipts (SRs) for the remaining 85 per cent. The SRs will be guaranteed by the government. The government guarantee will essentially cover the gap between the face value of the security receipts and realised value of the assets when eventually sold to the prospective buyers. The government approved a 5-year guarantee of up to Rs 30,600 crore for security receipts to be issued by NARCL as non-cash consideration on the transfer of NPAs. This will address banks/RBI concerns about incremental provisioning. Government guarantee, valid for five years, helps in improving the value of security receipts, their liquidity and tradability. A form of contingent liability, the guarantee does not involve any immediate cash outgo for the central government.

Friday, January 28, 2022

Some observations on the Chinese government policies

The troubled property giant China Evergrande may yet melt down and take out the remainder of the sector with it, but I have to admire Beijing for doing exactly what the US did not do in the run-up to the subprime crisis, by identifying problematic companies in advance of a crash, and attempting to let the air out of a bubble before it brings down the rest of the economy... sending executives who have broken the law to jail after a fair trial, and checking corporate excesses in advance of crisis, is a good thing. China has recently made some improvements in investor protection schemes and securities law. In November, Kangmei Pharmaceutical, formerly one of China’s largest publicly traded drugmakers, was found guilty of fraud and had to pay out $387m to investors. Chair Ma Xingtian and his wife, along with four former executives, were held personally financially liable, and Ma himself was jailed. Would that any number of American executives had received the same treatment amid the countless financial crises and corporate scandals of recent years.

4. The implementation of these policies have required the centralisation of the policy making in the Presidency, which in turn has ended up marginalising the traditional institutional structures even including the separations between the government and the Party, and the Party and the leadership.

Thursday, January 27, 2022

Return of the government - The Economist Survey

I blogged here on the upending of orthodoxy in economics and finance since the global financial crisis, which in turn has been hastened by the pandemic. Another related pandemic induced development has been the return of the state or government into several areas of the economy and our lives from where it had been ideologically banished.

The Economist has a survey on what it describes the "new interventionism". More than any financial share terms, it defines this trend more in terms of rising influence of government, especially in terms of four aspects - industrial policy, trust-busting, enhanced regulation, and taxation.

First is a renewed enthusiasm for industrial policy, defined as state support for favoured industries, technologies or specific firms, and guided by a desire to promote jobs or secure inputs needed for national security (computer chips) or the energy transition (batteries). Next is the expanding ambition of trustbusters that, tentatively in America, slowly in Europe and almost overnight in China, are moving from a focus on prices to a broader assault on corporate power to defend anything from small businesses to government itself. Third is the growth of regulation, particularly over the environment, labour standards and corporate governance, which cut across sectors and affect all large firms. And fourth is an inflection point in what had seemed an irreversible trend to lower business taxes, as politicians have followed voters in seeing unloved big business as a convenient source of revenue.

This is the crux of the argument for more government,

“Markets are good at allocating resources efficiently on a narrow understanding of efficient…What delivers highest returns to an individual investor is not necessarily in the economic interest of a nation,” says Oren Cass of American Compass, a right-leaning think-tank in Washington... Mr Cass blames the innovation drought on governments abandoning their role as midwife to technological breakthroughs, as they were for the internet and biotechnology.

There is another strategic dimension to the call for greater government, the emergence of China as a competitor. This sums up the market failure in this area,

Pat Gelsinger, boss of Intel, dislikes the flipside of being part of a sensitive industry—being barred by his government from selling products to China. “If Chinese customers want more chips from the us, we should say yes,” he suggests.

Profits trump all else, national security not even being a concern.

Nowhere has this return been felt more than in taking a leaf out of the Chinese playbook and pursuing active industrial policy,

In Japan 57 Japanese companies will get around $500m in subsidies to invest at home... The EU has doubled down on a consortium to make batteries, earmarked some €160bn ($180bn) of its covid-19 recovery fund for digital innovations, especially chips, and... launched five “missions”... In October President Emmanuel Macron unveiled the “France 2030” programme, which will spend €30bn over five years on ten areas from the specific (small nuclear reactors, medicines) to the vague (cultural and creative content production)... Tax relief for research and development, nearly half of which firms claimed for work done outside Britain in 2019, will be “refocus[ed]…towards innovation in the UK”... In one of his first acts as president, Joe Biden issued an executive order instructing government agencies to review supply chains, stretched to breaking point by the pandemic, to make them more “resilient”—which is to say more American... When a $25bn handout for semiconductor firms to make more advanced chips in America came up for a vote in the Senate in July 2020, 96 of the chamber’s 100 members voted in favour. The chip provision has since grown into $52bn and been folded into the $250bn Innovation and Competition Act, which includes $80bn for research on artificial intelligence (AI), robotics and biotechnology, $23bn on space exploration and $10bn for tech hubs outside Silicon Valley.

This is a powerful insight about practicing industrial policy,

“You don’t need the ability to pick winners. You need the ability to let losers go,” says Dani Rodrik of Harvard, whose paper in 2004, “Industrial Policy for the 21st Century”, helped to seed new interest in the notion.

The challenge is less to pick winners, but have mechanisms in place to screen out or withdraw support to losers or failures. The North East Asian success stories, as Joe Studwell demonstrates in his classic book, were successful in doing this.

Industrial policy today may be harder than in earlier times, being largely co-ordination problems.

With the Biden administration, competition policy in the US appears to be coming the full-circle,

... the antitrust philosophy that has dominated regulatory thinking and judicial decisions in the past half-century. Associated with Robert Bork, an American judge from the late 1970s, it held that consumer welfare and the protection of competition, rather than of particular competitors, should be the only goals of antitrust law. Business practices were deemed fine so long as they did not result in harm to consumers from excessive prices. Most mergers were either competitively neutral or enhanced efficiency, even if they led to oligopoly; only those creating a dominant firm or monopoly were likely to be bad for consumers. Bork’s work was itself a reaction to an earlier approach linked to Louis Brandeis, a former us Supreme Court justice. Brandeis believed that size was nefarious in itself. Curbing market power was a tool to fight other ills, such as mistreatment of workers, the stiffing of suppliers or even threats to democracy. This may have led to some perverse outcomes. In one notorious example in 1966, the Supreme Court blocked a merger between two grocers in Los Angeles with a combined market share of 8%... Mr Biden has installed “neo-Brandeisians” in senior trustbusting roles. Lina Khan, a 32-year-old academic, chairs the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Jonathan Kanter, a long-time Google-basher, heads the Department of Justice (DoJ)’s antitrust division. Tim Wu, a law professor whose books include “The Curse of Bigness”, is the White House adviser on technology and competition. “The speed of the takeover by the neo-Brandeisians of the regulatory apparatus has been extraordinary,” says one big asset manager.

Business concentration is a major problem,

According to The Economist’s calculations, two-thirds of 900-odd sectors covered by America’s economic census became more concentrated between 1997 and 2012. In half of these concentration has edged up further in the subsequent five years. In the two decades to 2017 the weighted average market share of the top four firms in each industry increased from 26% to 32%. The four biggest British firms accounted for a larger share of revenue in 2018 than a decade earlier in 58% of 600-odd subsectors. Concentration in the EU has been going in the same direction, albeit more slowly.

This is how the anti-trust movement is responding,

This new competition doctrine... expands the goals of antitrust policy in two main areas: merger control and business-model regulation. For most mergers and acquisitions (M&A), regulators used to restrict scrutiny to a small number of “horizontal” deals between firms active in the same market that, if combined, could reduce competition and allow incumbents to raise prices. Today all these tenets are going out of the window. Trustbusters now investigate “vertical” integrations between companies with separate lines of business, as well as horizontal ones with combined revenues that would not historically have warranted attention. A new procedure allows EU regulators to ask national authorities to submit deals that are potential killer acquisitions, particularly in the digital, pharma and biotech industries... In America the FTC and DoJ are making merger guidelines more stringent. M&A lawyers say the agencies are asking more questions, including about the impact of deals on the labour market. They already look beyond direct pecuniary harm to consumers. The FTC is backing a suit that seeks to break up Meta into Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, even though earlier regulators waved these takeovers through...The second avenue of antitrust expansion—dictating what dominant businesses can and can’t do—is more inchoate than tougher merger control. But it could prove more consequential... Several proposals would outlaw practices deemed anticompetitive. One would treat Amazon’s marketplace or Google’s search engine as essential to commerce, rather like a dominant railway operator, prohibiting them from favouring their own products over others. Another would force Apple and Google to open up their app stores to alternative in-app payment methods and search results. A third would shift the burden of proof from regulators to dominant companies, which would need to show that any merger or acquisition does not hurt competition, rather than the other way around. All three have Democratic and Republican co-sponsors. Other places are further along the regulatory route. The EU is preparing to adopt two laws, the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act. South Korea has enacted one that eliminates app stores’ monopoly on payments.

This on greater regulation of businesses in a host of areas,

“Tenets of ESG are becoming hard law,” says Mr Rodrik of Harvard. A draft EU directive would require firms to monitor, identify, prevent and remedy risks to human rights, the environment and governance in their operations and business relations. France’s “Duty of Vigilance Act” of 2017 already requires French companies with over 5,000 employees in France or over 10,000 worldwide to monitor their firms, contractors and suppliers for potential abuses. By mid-2023 a Dutch law aimed at stopping child labour will take effect, after a three-year grace period. A similar supply-chain act has been passed in Germany. America’s Build Back Better bill is dotted with requirements for companies to employ unionised workers. The House of Representatives has passed a bill that would reverse many constraints on union power, some dating from 1947... Governments everywhere seem suddenly to have become much keener on labour protection... The European Commission wants common rules on minimum pay and “platform workers” who ferry passengers for Uber or meals for Deliveroo... Financial regulators are also becoming more intrusive. The Bank of England is conducting climate-risk stress tests. The European Central Bank is considering requiring firms to disclose exposure to climate-related risks, including assets that may become stranded by tougher climate legislation... A final set of rules encumbering business reflects strained Sino-Western relations.

On the final area of rising government influence, corporate taxation, the last four decades has a seen a sharp decline in tax rates.

Between 1985 and 2018 the average corporate-tax rate fell from 49% to 24%. Many tax havens charge zero... Companies have also learned to pay less tax by shifting reported earnings, which is easier with the rise of intangible assets such as brands. Although only 5% of American multinationals’ foreign staff work in tax havens, they book nearly two-thirds of foreign profits there, twice as much as in 2000. In 2016 around $1trn of global profits were booked in “investment hubs” such as the Cayman Islands, Ireland and Singapore, whose average effective tax rate on profits is 5%. According to an oecd study in 2015, this robbed public coffers of $100bn-240bn a year, equivalent to 4-10% of global corporate-tax revenues.

Monday, January 24, 2022

Market failure in financial markets - the case of plentiful venture capital

The Valley’s “always tell the truth” sermon is reductionist and hypocritical. It ignores the fact that many of our nation’s most valuable companies are priced on promises of technologies that don’t exist. The entire venture capital industry, in fact, is predicated on promising things that don’t exist. Microsoft, perhaps the most successful tech company in history, got its break when Bill Gates sold IBM an operating system he didn’t have... Allegedly, an engineer at the company coined the term “vaporware” a year later. Promising something that doesn’t exist is as central to the Valley ethos as late-night coding sessions, hoodies, and the hallucination that the public has asked you to solve the world’s problems vs. just do less damage...The line between vision and fraud is only drawn in hindsight. We set arbitrary deadlines for entrepreneurs to deliver on their vision, and their vision only becomes fraud when we say time’s up. What if Holmes, with five more years and another billion dollars, shipped a working product? Or pivoted to a home-testing machine for an acute respiratory syndrome?... When valuations are overwhelmingly driven by stories, things can get ugly. Investors will do whatever it takes to defend their narrative — their investment depends on their flocks screaming “heretic!” at anybody who questions the scripture, as the foundation doesn’t hold up to more modern orthodoxies (i.e. math)... Swarming anyone who questions the narrative is a built-in feature of stocks and sectors that have gotten too far out over their skis.

This is a real hard one. There is no way to distinguish and police fraud. The line between vision and fraud is blurred, and it's inevitable that entrepreneurs take advantage and push agendas.

It's almost become second nature for entrepreneurs to knowingly exaggerate the claims about their innovations and ideas. From there, it's a tiny step to present those claims as facts. This is all seen as acceptable within the broad boundaries of marketing one's ideas. In a different world, not too long back, several of Elon Musk's claims and forecasts would have been seen as being atleast deliberately misleading.

Logic is a beautiful servant. It can be deployed to justify almost anything. Even if Trevor Milton did indeed push the truck down the slope, Nikola's promise was enough to condone this indiscretion as an enterprising action to attract capital to very promising idea. If Nikola becomes successful, this fraud would become sanctified and become an important part of VC folklore.

The attitudes and behaviours of a generation of youngsters watching starry-eyed at the venture capital industry, either as aspirants or as junior professionals, are likely shaped by this environment and its prevailing culture.

Venture capital's value proposition is its ability to identify and finance promising ideas and entrepreneurs. Investing in new ideas have always demanded risk appetite. This was a three-way trust game between investors, venture funds, and entrepreneurs. Financiers were generally careful and discerning enough to screen out the frauds. When capital was scarce and competing demands too many, entrepreneurs were chasing finance. This imposed a natural discipline to financing and investment decisions. It also shaped the expectations and behaviours of entrepreneurs.

But things changed when capital became plentiful enough to start chasing entrepreneurs. Investors searching for yields had limited opportunities. Venture capital was packaged by consultants and other industry boosters as the most promising opportunity. Capital flooded into venture and other alternative finance vehicles, so much so that deploying them productively with reasonable due-diligence became a problem. Compounding matters, as analysts and opinion makers sang its praises, fund managers could not afford to miss out on the next big idea. And there were so many such big ideas. Almost anything could pass off as a great idea.

Worse still, once invested, the sunk cost fallacy meant that fund managers are loath to cut losses. Their incentives are aligned to overlook the emerging evidence about the innovation and maintain the pretence to keep capital coming. And more the investment made, greater this incentive alignment. Finance loses its disciplining powers.

In more general terms, the plentiful cheap capital has distorted incentives all round, and financial discipline has become a casualty at all levels.

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Weekend reading links

1. From a few months back, Andy Mukherjee peers ahead into the future of banking in the Indian context,

Google Pay wants to push time-deposit products of small Indian banks that don’t have much of a retail liability franchise of their own. According to a press release, Equitas Small Finance Bank will offer Google Pay customers up to 6.85% interest on one-year funds as part of a “branded commercial experience” on the platform... The move has global significance. It shows the tenuous nature of the hold financial institutions have on a core operation like deposit-taking, and their vulnerability to an assault from online search, social media and e-commerce behemoths. Alphabet, Facebook Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. may pose a far bigger challenge to brick-and-mortar lenders than fintech startups that don’t have the scale of platform businesses. Just like in India, deposit-strapped challenger banks might throw the keys to tech intermediaries with hundreds of millions of active users. When the giants storm the fortress, even larger banks will lose control of banking..China’s homegrown tech titans have already shown how easy it is to dislodge traditional lenders from lending... India’s deposit-taking institutions don't have any special advantage left in moving retail money. Yes, they still hold the accounts for sending or receiving funds. But rather than transacting on their bank apps or cards, customers prefer to use Google Pay or Walmart Inc.’s PhonePe to pay one another and merchants... Since it won’t even take two minutes for a platform to book deposits from scratch, if another lender offers a better deal, idle funds might go there next. Customer loyalty, which is often just plain inertia, will no longer ensure stickiness... For a fee, platforms can easily extend their insights into consumer behavior and payment flows to influence deposit mobilization. The higher the commission, the lower the banks’ profit... Regulated institutions may be left holding a license to take deposits--and a thick rule book accompanying that privilege--but platforms will decide if a bank’s promotional offer is to be displayed prominently or buried in an obscure corner. The same slow, painful decline that gutted the print media after readers and advertisers moved online and publishers lost their sway over them may be waiting in the wings for banking, too.

2. FT has an interesting report on Dominic Cummings, former chief of staff to Boris Johnson and one of the leading forces behind his Brexit campaign. Cummings who courted numerous controversies during his tenure with Johnson at 10 Downing Street had a very bitter break-up with his boss, and is now leading a concerted campaign of leaks and media attacks to bring down Johnson.

When he was at 10 Downing, Cummings, with his views on technocracy and scorn for the bureaucracy, had become a sort of poster child for tech-enthusiasts and supporters of bureaucratic reform. But as events since have shown, his hypocrisy and duplicity in trying to unseat Johnson reveals a dangerous and petty mind, one who is best kept as far away from the public realm as possible.

3. Business Standard reports on the near extinction of Indian mobile phone makers and the rise and rise of Chinese ones.

5. India's formal sector too may not be out of the woods,

Since the onset of the pandemic, the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) has allowed members to avail of an advance to deal with expenses arising from Covid-19. Data from EPFO shows that between April 2020 to September 2021, 1.5 crore such claims were received. This implies that 23 per cent of India’s formal labour force (an upper limit, based on those contributing to EPFO) has availed of this facility. (Members were allowed to do so twice from June 2021). Of these 1.5 crore claims, 87.2 lakh were received in 2020-21. This works out to an average of 7.26 lakh claims per month. In comparison, in just the first six months of 2021-22 (April-September), 63.4 lakh such claims were received, at an average of 10.5 lakh per month. This suggests that not only has the formal labour force continued to face economic hardship, but also that it has been of a similar if not higher magnitude in the ongoing financial year.

It would be useful to compare these trends with the pre-pandemic share of EPFO members availing advances.

6. Ganesan Karthikeyan has an interesting article where he argues that the endgame for Covid 19 has began. He claims that unlike till now, when the dominant mutants seek to maximise transmissibility, once large proportion of population are either immunised or infected the mutations that provide the virus with an evolutionary advantage are ones that help it evade immunity. Such mutants are more likely to produce milder illnesses so that its transmissibility is less reduced.

He also makes an interesting point about what happens when the pandemic ends,

As has already become evident, we aren’t going to have lifelong protection after infection or vaccination. It is reasonable to expect that the virus will continue to mutate to evade immunity. Of the several unsavoury scenarios, one optimistic (and perhaps also likely) possibility is that the virus continues to circulate but infects only people without immunity — children born after the pandemic, older adults, or others with waning immunity. These vulnerable individuals will continue to require vaccination. This is presumably what happened after the 1918 pandemic. That virus now causes seasonal influenza.

Excellent primer on Omicron with links to latest research.

7. The Economist makes an important point about China's AI ambitions

Despite leading America in the overall number of AI-related publications, China produces fewer peer-reviewed papers that have academic and corporate co-authors or are presented at conferences, both of which are typically held to a higher standard. It ranks below India, and well below America, in the number of skilled AI coders relative to its population. These shortcomings are likely to persist, for three reasons.First, capital may not be being allocated efficiently... Beijing has created a system for rewarding local officials that favours debt-fuelled spending and seldom punishes wastefulness. Many state AI investments have been “reckless and redundant”... Jeffrey Ding of Stanford University. Zeng Jinghan of Lancaster University has documented the rise of firms that falsely claim to be developing AI in order to suck up subsidies. One analysis by Deloitte, a consultancy, estimated that 99% of self-styled AI startups in 2018 were fake... China’s second problem is its inability to recruit the world’s best AI minds, especially those working on high-level research... Though about a third of the world’s top AI talent is from China, only a tenth actually works there. A shortage of non-Chinese researchers further handicaps China’s capabilities... Even more problematic for the party, its master plan ignored the cutting-edge semiconductors that power AI. Since its publication Chinese companies have found it ever more difficult to get their hands on advanced computer chips. That is because virtually all such microprocessors are either American or made with American equipment. As such, they are subject to restrictions on exports to China put in place by Donald Trump and extended by his successor as president, Joe Biden. It will take years for Chinese companies to catch up with the global cutting-edge, if they can do it at all.

8. Scott Galloway points to the graphic that shows more than half US corporate profits are booked in tax havens, compared to roughly 5% in 1966.

Considering that so many doubts about the “robots kill jobs” narrative have arisen, it is not surprising that a different thesis is emerging. In a recent paper Philippe Aghion, Céline Antonin, Simon Bunel and Xavier Jaravel, economists at a range of French and British institutions, put forward a “new view” of robots, saying that “the direct effect of automation may be to increase employment at the firm level, not to reduce it.” This opinion, heretical as it may sound, does have a solid microeconomic foundation. Automation might help a firm become more profitable and thus expand, leading to a hiring spree. Technology might also allow firms to move into new areas, or to focus on products and services that are more labour-intensive.A growing body of research backs up the argument. Daisuke Adachi of Yale University and colleagues look at Japanese manufacturing between 1978 and 2017. They find that an increase of one robot unit per 1,000 workers boosts firms’ employment by 2.2%. Another study, by Joonas Tuhkuri of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (mit) and colleagues, looks at Finnish firms and concludes that their adoption of advanced technologies led to increases in hiring. Unpublished work by Michael Webb of Stanford University and Daniel Chandler of the London School of Economics examines machine tools in British industry and finds that automation had “a strong positive association with firm survival, and that greater initial automation was associated with increases in employment”... The methodology used by Mr Adachi and his co-authors is particularly clever. One problem is untangling causality: firms on a hiring spree may also happen to buy robots, rather than the other way round. But the paper shows that firms buy robots when their prices fall. This helps establish a causal chain from cheaper robots, to more automation, to more jobs.

Friday, January 21, 2022

On the inflation debate - a note of caution

Arguably the most important macroeconomic debate of present times is whether inflation is transitory or persistent. Emerging signals and the commentary around it appear to be making opinion makers gradually veer around to the view that it may be persistent. We are at a critical moment in this debate since it's the time when the opinion flips definitively and actions follow suit.

In case of something like inflation, where expectations are perhaps more important than even the dynamics of the substantive underlying forces, it's important to not let our guard down and allow the decision to be made purely on momentum. Persistent inflation is now a momentum trade on a strong upswing. In such times, it's important to keep track of the rear-view mirror and transitory inflation proponents.

Consider the following. For inflation to become persistent, the following has to happen

- The underlying inflationary contributors have to play out

- These forces have to leave permanent effects

- The price pressures have to become broad-based enough

- They have to persist for long-enough

- Enough opinion makers will have to be convinced of a definitive turn

- And these opinion makers end up shaping expectations among the public at large

Given the failure of (all?) models, I think it’s important to recognize that any explanation for why inflation has surged over the last year is improvised – it has no track record of being right or wrong. We’re all Bayesians now! But some are more convincing than others.

On whether inflation is transitory or persistent, Adam Tooze makes the case that there is not enough evidence of broad-based and longish enough nature of the inflation trend to argue that it's persistent in either Europe or US.

There are some important signatures which cannot be ignored. For one, as this graph on the US inflation conveys, almost two-thirds of the deviation in US retail inflation from pre-covid trend is contributed by motor vehicles and energy prices.

Then there is the services sector dog that did not bark. Services, which forms the bulk of CPI weights, remains largely unaffected by any new inflation trend.

Martin Sandbu parses the latest US inflation data and is not convinced. He has a compelling case.

It's acknowledged that the supply-chain disruptions due to the pandemic have been the most important immediate trigger. The supply-chain disruptions likely became amplified when the pent-up demand got released and boosted aggregate demand at the extensive and intensive margins. The increased disposable incomes and pent-up demand (extensive margin) was coupled with the re-allocation of consumption (intensive margin) away from services to goods due to the pandemic enforced closures and work from homes. How long will these trends last is anybody's guess.

Adding more uncertainty to the calculations is the future of Covid 19. Is Omicron the end-game for elevated Covid? If it's the case that Omicron is the end-game then several assumptions made by the persistent-camp becomes questionable.

We need to be cognisant that "this time is no different" explanations may have only limited relevance given the unique nature of the shock - sudden supply and demand shocks, followed by equally sudden release of pent-up demand but very slow release of supply constraints (or even persistence of certain supply constraints), and all of this happening in a world awash with liquidity.

In conclusion, this is an important observation from Adam Tooze,

All things considered, the main reason to worry about inflation may be precisely that people are talking about it. Whatever its effects in the markets, in the political arena inflation talk is not neutral. Inflation tends to hurt the Democrats... If one takes this argument seriously, then what the Biden administration needs is for the Fed to do the bare minimum necessary to anchor inflation expectations, calm public fears and the markets. Unfortunately, the calm in the markets is now based on pricing in four interest rate hikes. Let us hope that this is not more than the economy can bear.

Update 1 (23.01.2022)

NYT has this good summary of the demand for goods in the US,

Virus outbreaks shut down factories, ports faced backlogs and a dearth of truckers roiled transit routes. Americans still managed to buy more goods than ever before in 2021, and foreign factories sent a record sum of products to U.S. shops and doorsteps. But all that shopping wasn’t enough to satisfy consumer demand. The Port of Los Angeles is a window into the mismatch. The port had its busiest calendar year on record last year, processing 16 percent more containers than in 2020. Even so, it still has a huge backlog of ships waiting to dock, several of which, as of Friday, have been waiting a month or more...Giving households more money to buy camping equipment or a new kitchen table widened the gap between what consumers wanted and what companies could actually supply. As goods came into short supply and began to cost more to transport, businesses raised their prices. Government checks haven’t been alone in driving strong U.S. demand. As virus fears prevent consumers from planning a trip to Paris or a fancy restaurant dinner, many have turned to refurbishing the living room instead, making goods an unusually hot commodity. Lockdowns that forced families to abruptly stop spending at the start of the pandemic helped to swell savings stockpiles. And the Federal Reserve’s interest rates are at rock bottom, which has bolstered demand for big purchases made on credit, from houses and cars to business investments like machinery and computers. Families have been taking on more housing and auto debt, data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows, helping to pump up those sectors.

Update 2 (30.01.2021)

Philipe Hildebrand makes the case that the inflation is being driven not by any demand but by supply-side shocks. He points to this BlackRock research paper which highlights the unprecedented nature of the supply disruptions.

It also points to the Covid induced shifts away from services to goods.Thursday, January 20, 2022

PPP fact of the day

From Patrick Jenkins in FT

Data from Britain’s National Audit Office show volumes peaked in 2007 at £8.6bn, when more than 60 deals were struck, dwindling to virtually nothing in recent years. German enthusiasm for PPP has shown a similar pattern of decline, although the numbers are much smaller — at the 2007 peak, 38 deals worth a combined €1.5bn were done, according to Partnerschaft Deutschland, an advisory group. In 2019, the last year for which data are available, only three deals were done, worth just €66m. Those patterns reflect a mixed verdict on the effectiveness of PPP. The UK NAO has been critical of the value for money achieved on an array of projects since the 1990s.

As I have blogged on several occasions, in the case of developed country governments which have strong state capacity, public procurement should prevail over PPPs unless there are clear efficiency improvements possible. The negatives of PPPs - higher cost of capital, incentive distortions that lead to the likes of asset stripping and dividend recapitalisations - are likely to far outweigh any benefits in case of developed economies. The UK is the best exhibit for this case.

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Expert knowledge, public policy and the pandemic response

Then there is the sheer complexity of the challenge at hand. To understand it, consider the following set of questions that Howard Marks posed in the context of the emerging SARS Cov 2 pandemic in May 2020.

Who can respond to this many questions, come up with valid answers, consider their interaction, appropriately weight the various considerations on the basis of their importance, and process them for a useful conclusion regarding the virus’s impact? It would take an exceptional mind to deal with all these factors simultaneously and reach a better conclusion than most other people.

He writes about the challenge of making forecasts in the face of uncertainty, and the skills required to be able to make good judgements. This is not about some rote application of technical knowledge. When faced with decision that need to balance several strands of considerations and requirements, it's more an exercise in trying to make practical judgements. That's the realm of public policy and not technical expertise.

As a physician, I was trained first and foremost to think of the individual in front of me… Physicians tend to be conservative in their practice of medicine. We fear a bad outcome disproportionately and will do almost anything to prevent it… But blown to the scale of a whole country, that kind of focus on individuals has often led us in the wrong direction during the pandemic. Much of my frustration at the response to Covid is that too many officials in senior positions at the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention seem to be thinking this way — if something isn’t close to perfect or doesn’t maximize the safety of each individual person, it’s not worth it at all.

For example, a focus on doing the “best” for the individual leads to a belief that if you’re going to test people for the coronavirus, the tests used must be of the highest quality, and that’s a professionally collected PCR, even if those tests are harder to perform and supplies are limited. Focusing on the individual can also lead to excessive fears of bad outcomes, even if they’re rare. Leaders can come to think that any risk of infections is unacceptable, leading to policies that close schools even though the danger that schools appear to pose is low.

A population-level view, on the other hand, often focuses on reaching as many people as possible rather than perfection. This view argues that repeated and regular testing is preferable, and that’s more easily done with tests taken at home even if they’re less sensitive than P.C.R.s in some ways. That the F.D.A. and the C.D.C. have trouble recognizing the utility of at-home tests as a public health tool, as opposed to purely a clinically diagnostic one, shows the shortfalls of always seeking the best. More frequent imperfect testing may pick up more cases, even if we miss a few we might have caught with perfect tests. Getting many people to be somewhat safer might achieve more than getting fewer people to be really safe.

Just this week, my own state, Indiana, made a decision through an individual lens and not a population one. We are running short on rapid antigen tests at state-run sites. The state therefore chose not to use them at all for adults ages 19 to 49. Instead, they’re prioritized for those 50 and above as well as children, and patients have to be symptomatic to get a test.From a clinical lens, this makes sense. You want to save the tests for those at highest risk. Most younger adults will be fine, while older, sicker people might need more attention. But from a population lens, this is the absolutely wrong choice. A test does not prevent you from getting Covid; it gives you the information you need to avoid spreading it. Young people may be at low risk individually, but they’re a big risk to others because they often go out and interact with people. Rapid tests are ideal for them.

The third one is about masks,

If you can have only the best, you’ll focus on N95 masks, see they are in short supply at the start of the crisis and tell most people they shouldn’t wear masks at all because only certain ones provide the best protection, and we have to save them for those at highest risk. A population-level view argues that cloth or surgical masks — which aren’t anywhere near as good as N95s but were easier to get — would lower the risk for everyone when the pandemic was beginning, and therefore would be helpful. It took until April 2020 — many weeks into the pandemic — for the C.D.C. to recommend mask wearing for the general public.

The point of all these is to provide the perspective on expert knowledge and public policy.

This blog came to the view very early on in the pandemic that much of the debates and narratives around Covid are consciously or unwittingly being framed around the works of narrow expertise and powerful interest groups. And they are deceptive or plain wrong or dangerously misleading. Worse still, the veneer of respectability around these opinions and advisories means that they crowd-out even common-sense. Any practical suggestion, based on exercise of judgement, is decried and stigmatised.

Given all the above, a simple response to the pandemic going forward could be - enforce masking, prioritise vaccination (including boosters), continue normal testing, maintain surveillance and limit large gatherings based on any increase in case trends, and get back to normalcy in life. And especially important is to not close down schools since the one lasting legacy of the pandemic is most likely to be the irretrievable loss of learning years with its consequences on economic output for a cohort of learners. Note that this blog had said much the same as early as March 30, 2020. While elements of this response are grounded on firm evidence, the response as a whole is an exercise of practical judgement.

On closely related notes, I have blogged earlier on the "smartness" dominance in development debates, the distinction between being smart and wise, the twin tyrannies of quantitative methods and expert wisdom, challenge of marrying experiential and evidentiary knowledge, the ideology of evidence-based policy making, marginalisation of priors and elevation of evidence generation in policy making, and the trend of ahistoricism and data analytics in economics.

Monday, January 17, 2022

The sayer-doer dissonance on public policy issues

This is a post on the glaring dissonance between the roles of those who advise and those who implement public policy.

Roger Federer or Virat Kohli lean on their coaches to improve their games. Traders and fund managers apply the research supplied by their institution's research divisions and finance professors. Chief Executives seek the opinions of management gurus (and consultants). Politicians seek the advise of pollsters and campaign managers. And so on.

In all these cases, there is a clear distinction between those who advise and those who actually do. The sayer and doer are different.

The advisors are informed by their knowledge of the why and what ought to be done, the concepts and theoretical frameworks of the issue. The doers are informed by their judgement of what is possible and doable given the circumstances.

Each side understand their role and acknowledge it. The sayers draw on their concepts and analytical frameworks to supply the inputs which the doers can apply in their decision making. The doers screen the inputs from the sayers by drawing on countless insights and data points from their practical experience, and thereby exercise good judgement in their decisions.

The sayers acknowledge the limitations and narrowness of their knowledge, the absence of insights and data points gathered from the experience of a lived life. This gives them an epistemic humility. Accordingly, neither coaches, nor scientists, nor researchers claim greater wisdom in the application of their outputs than their respective practitioner counterparts. Functional transgressions are rare and not favourably looked on by all concerned.

The acknowledgement of role distinction comes from their respective expertises and perspectives. The sayer's expertise is largely theoretical. The doer's is experiential, the lived experience of doing things. The sayer has the comfort and luxury of working in sanitised environments - contemplating, theorising, designing and experimenting. The doer has to respond to the issue in real-time and based on a multitude of emerging contexts and scenarios.

It's accepted that the doers will apply their judgement to the outputs of sayers and tailor their responses accordingly. It's therefore also accepted that these responses will sometimes incorporate the inputs from the sayers, sometimes modify them, and sometimes reject them. It's considered the normal course of things in their respective areas. Flawed judgements by the doers are assumed to be part of the deal.

Similarly, in the case of economy and public policy too there are advisors - economists, public policy analysts, commentators etc - and doers - policy makers and implementors within governments.

But in stark contrast to the other domains, the lines of role separation blurs disappears in the case of public policy issues. While sports coaches, finance researchers, management gurus, and consultants acknowledge the limitations of their knowledge in its real-time application by players, fund managers and chief executives, the same does not apply with respect to economics and public policy researchers and opinion makers in their engagement with bureaucrats and politicians. The sayers believe they can also be the doers and refuse to cede space to the judgement of doers (with all its inevitable risks of failure etc). The space allowed for doers to make their judgement is scarce, often even unavailable. In their view, expertise has to prevail.

This is surprising since, if anything, given their innate complexity the space for judgement should be much higher in policy making. Accordingly, policy makers and implementors face an objective function whose variables are the technical merits of the proposal, its political acceptability, its bureaucratic feasibility, and the present state of the system. In other words, policy making is the application of judgement to historical legacy, context (read society, state capability, political economy etc), and expertise. Decision-making using this objective function is invariably an exercise in judgement. It's a different matter that the judgement may occasionally be flawed.

There are a few reasons for this dissonance in the field of public policy. One, unlike other domains, which are ring-fenced and distant, policy making and implementation, being proximate and universal in their impacts, provide a much greater space and incentive for perceptions and opinions formation and advisories. Two, there is an entrenched narrative that governments are untrustworthy and inefficient, and politicians and bureaucrats are generally corrupt and incompetent, coupled with the perception of experts being competent and objective. Three, the entrenched narrative also fuels the belief that the solutions to public policy challenges are primarily about the application of technical knowledge and expertise. Finally, the public nature of the issues involved makes dissonance more salient, triggers public discussions, and attracts disproportionate media attention compared to the private nature of the dissonance between, say, a fund manager and his/her research team.

The underlying assumptions are deeply questionable. Unfortunately, they form part of the dominant narrative of our times. It'll no doubt change with time. But will come at a prohibitive cost. Changing the narrative requires counter-narratives and stories that are strong enough to dismount the prevailing narrative.

Instead of helping policy makers improve the quality of their judgement, so as to be able to exercise good judgement, the debate is focused on elbowing out non-expert judgement and applying narrow technical expertise on important public policy issues. The pandemic response and issues related to climate change and energy transition are good examples of this struggle.