The Covid 19 pandemic has underscored the perils with efficiency maximisation at all costs and the importance of resilience. The excessive concentration of manufacturing, especially of critical Pharma products, in China and the supply chain disruptions have provided the most salient reminders. This post discusses the problems of pursuing efficiency at all costs and to the exclusion of all else in case of global manufacturing supply chains.

I have blogged extensively on the topic of prioritisation of efficiency at the cost of all else here (push for renewables and spot market purchases in energy markets), here (efficiency-resilience trade-off), here (efficiency-resilience in supply chains), here (Just-in-time SCM), here (natural gas), here (Pharma/vaccine manufacturing), and here (Amazon HR practices).

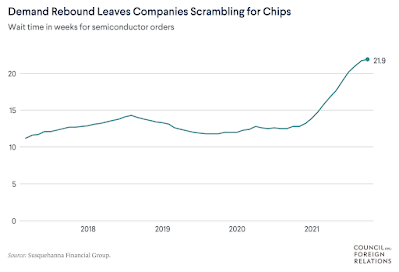

FT has a long read about this market failure in the case of supply chain management (SCM), All over the world, companies have encountered snags in their supply chains during the pandemic and the shipping bottlenecks that have followed as economies restarted. Car production lines have been halted by a lack of semiconductors, liquor distillers have run out of bottles and department stores are short of Christmas stock. Such troubles are forcing a rethink of corporate strategy. For decades, companies prioritised costs above all else when selecting suppliers, building factories and deciding how much stock to keep on hand. This philosophy was often dubbed “just in time” because it emphasised keeping inventory to a minimum and using short-term, flexible contracts that could be adjusted quickly to changes in demand. But the drive for efficiency encompassed far more than that. Companies also moved production to low-wage locations, consolidated orders to maximise economies of scale, and tried to minimise their physical presence in high-tax jurisdictions... Companies that had consolidated their production into one or a few low-cost locations got a nasty shock last year as pandemic-related shutdowns and shipping bottlenecks left them without key parts or even merchandise to sell.

Businesses are responding to the pandemic induced problems,,

Some businesses are increasing the inventory they keep on hand and entering into longer term contracts with key suppliers. Others are diversifying their manufacturing to create regional hubs with local suppliers and investing in technology to give them greater advance warning of potential bottlenecks. Some companies are also investigating ways of working with their rivals to share information to develop emergency back up facilities without falling foul of competition regulators. “What companies love to do is to optimise working capital. So many manufacturers went to just-in-time inventory, and, pre-pandemic, that worked pretty well,” Carol Tomé, chief executive of UPS, said at a recent industry event. “But when the pandemic hit and everything was shut down, including manufacturing, and then the economy started to open and the demand . . . jumped, well, that just-in-time inventory didn’t work any more. Companies are now thinking about, I need ‘just in case’ inventory,” she added...

One big German industrial group caught flat-footed by the semiconductor shortage has shifted from three-month non-binding arrangements with suppliers to 24-month commitments that require it to pay in advance of receiving its chips. “We had to give the supply chain more stability,” a top executive says. “It’s a change from a buyer’s to a seller’s market.” It is not alone. US carmakers Ford and GM are setting up partnerships, rather than just supplier contracts, with semiconductor manufacturers to improve their access to chips. Their German rival Volkswagen is looking at extending the length of its contracts with key suppliers, and Chinese energy groups have been rushing to sign liquefied natural gas contracts that extend as long as 20 years, more than double the old normal length.

Its impact is being felt across the economy,

As a result, warehouse costs are rising sharply in many markets, as manufacturers and retailers boost inventory levels. US industrial vacancy rates — a measure of available warehouse space — hit a historic low of 3.6 per cent nationally in the third quarter, according to CBRE. In California’s Inland Empire, a key bottleneck near the ports of Los Angeles, vacancy rates scraped 0.7 per cent. And property agent Cushman & Wakefield predicts the UK could run out of warehouse space within a year... Multinational companies are now talking about “local for local” supply chains. That’s partly because logistics problems have eaten away the advantages of shipping products from low-cost factories half a world away. It now takes anywhere from 28 to 52 days to ship a pair of shoes produced in China from Shanghai to Los Angeles, up from between 17 and 28 days before the pandemic. And the total cost has gone up by $1.77 per pair, according to research by consultancy AlixPartners — an additional cost which smaller industry members with slimmer profit margins will struggle to absorb... Manufacturers and retailers of everything from cars and footwear to vaccines are rediscovering the advantages of having suppliers closer to consumers. In strategically important sectors such as healthcare, they are also receiving government support. This is reviving interest in manufacturing in North America.

A survey of senior executives from global supply chain leaders by the consultancy McKinsey highlight some of the aforementioned trends.

It highlights an important point about how digitisation and analytics focus on the operational performance and efficiency improvements and gloss over issues of risk management,

Today’s ongoing and planned digitization efforts are most likely to focus on visibility, as companies strive for a better picture of their supply chains’ real-time performance. For example, since May 2020, 30 percent of respondents had implemented new digital performance-management systems—an important enabler of supply-chain visibility. Improved planning tools, either for specific aspects of the supply chain (such as logistics management) or broader end-to-end planning systems, come a close second among the companies in our survey, with more than three-quarters saying they were a priority. Just under half of all respondents also say they are looking at network-modeling tools to help them improve supply-chain design in the longer term. Nevertheless, despite the prevalence and impact of supply-chain shocks over the past two years, only 39 percent of companies are investing in tools to monitor risks and disruptions.

While some of the responses are perhaps exaggerated and likely to taper off once the pandemic subsides, it's reasonable to claim an overall shift away from efficiency maximisation above all else and towards resilience. A host of other factors - increased protectionism, climate change related actions, automation, increased labour costs in China and elsewhere, global tax harmonisation initiatives etc - are tailwinds to support this shift.

So what's the broader takeaway?

Thanks to business schools and management gurus, it had become articles of faith that businesses should outsource, focus on comparative advantage, specialise functionally, concentrate suppliers and production facilities, minimise inventories, tighten supply chains, contract labour services, minimise tax payout through tax avoidance, and so on. For sure, when done in proportion, all of them have merits and are desirable. But when taken beyond reasonable proportions, they generate distortions.

A common underlying factor behind all these concepts is efficiency. Conventional wisdom has it that their pursuit leads to greater efficiency in some form or other (mainly cost reduction), all of which generally lead to greater profitability, the primary objective of businesses. Therefore efficiency maximisation by pursuing these concepts to their extremes becomes an innate and inexorable dynamic of the market. It does not help that globalisation and advances in information and communications technology and transportation end up furthering these trends.

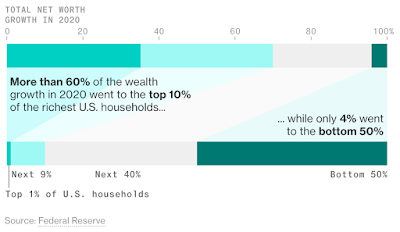

Businesses and consumers doubtless benefited from these trends. It led to cost reductions which got distributed between higher profits (for businesses) and lower prices (for consumers). A virtuous cycle of consumption, production, and trade led to expansion of aggregate output.

Then the pandemic struck. Lockdowns and quarantines ensued. Supply chains were disrupted. Outsourced suppliers and producers were cut-off or failed to keep their commitments. The lack of diversification at country and company levels among suppliers and producers became painfully evident. Businesses realised that their pursuit of efficiency maximisation and cost reduction had gone too far.

This was largely unfettered free-markets at play. Businesses faced competition and had access to producers, suppliers, and labour in a global market. And environment was created where maximising efficiency and cutting costs, above all else, became the overwhelming objective of businesses. This dynamic was creating faultlines every where. It was a teachable exhibit on the failure of unfettered markets.

This post highlights the problems with the efficiency maximising supply chain integration complement to the dominant shareholder capitalism of today. Just as the former marginalised resilience for efficiency maximisation, the latter marginalised stakeholder welfare for profit maximisation. There, as here, markets failed to not only prevent the emergence of distortionary trends but actually ended up amplifying those trends.

Update 1 (24.12.20210

FT has an article on the supply chain for an electronic bicycle, Pedego.

Here is the story of factory to customer story of Pedego's Element e-bike,

Pedego uses eight factories located across Asia. Once an Element bike order is placed, its more than 50 components are assembled at a plant in Shanghai. After factory inspection of the product, the assembled bikes are transferred to be shipped from Shanghai, where it can take up to two weeks to find a shipping container. Depending on the size of the container, each shipped container holds 150-224 bikes. After two weeks on the ocean, the shipment arrives at the Port of Long Beach, only to then wait up to six weeks at the port due to severe delays in docking ships and unloading containers. Once the shipments have been unloaded at the port, they are loaded onto trucks to be transferred to Pedego's nearby warehouse in Orange County. Finally, the bikes take one to two weeks to ship from the California warehouse to one of 200 Pedego dealerships across the US, including the store in Winnetka, Illinois.