I have blogged extensively on the water privatisation in the UK. This is about the ongoing crisis at Thames Water, this and this are about the balance sheet of UK water privatisation, this is about regulatory failure/capture and returns maximisation incentives of investors, and this is about the UK’s infrastructure privatisation in general.

After teetering on the brink of default, Thames Water has managed to get a proposal from a bunch of creditors for a £3bn emergency loan, enough to cover operations till at least next October or even May 2026. The loan has received government approval. But the emergency loan comes with a headline interest rate of 9.75 per cent, and the company spent over £50mn on advisers in raising the debt. It’s also in the process of finding new equity investors, and restructuring its complex capital structure.

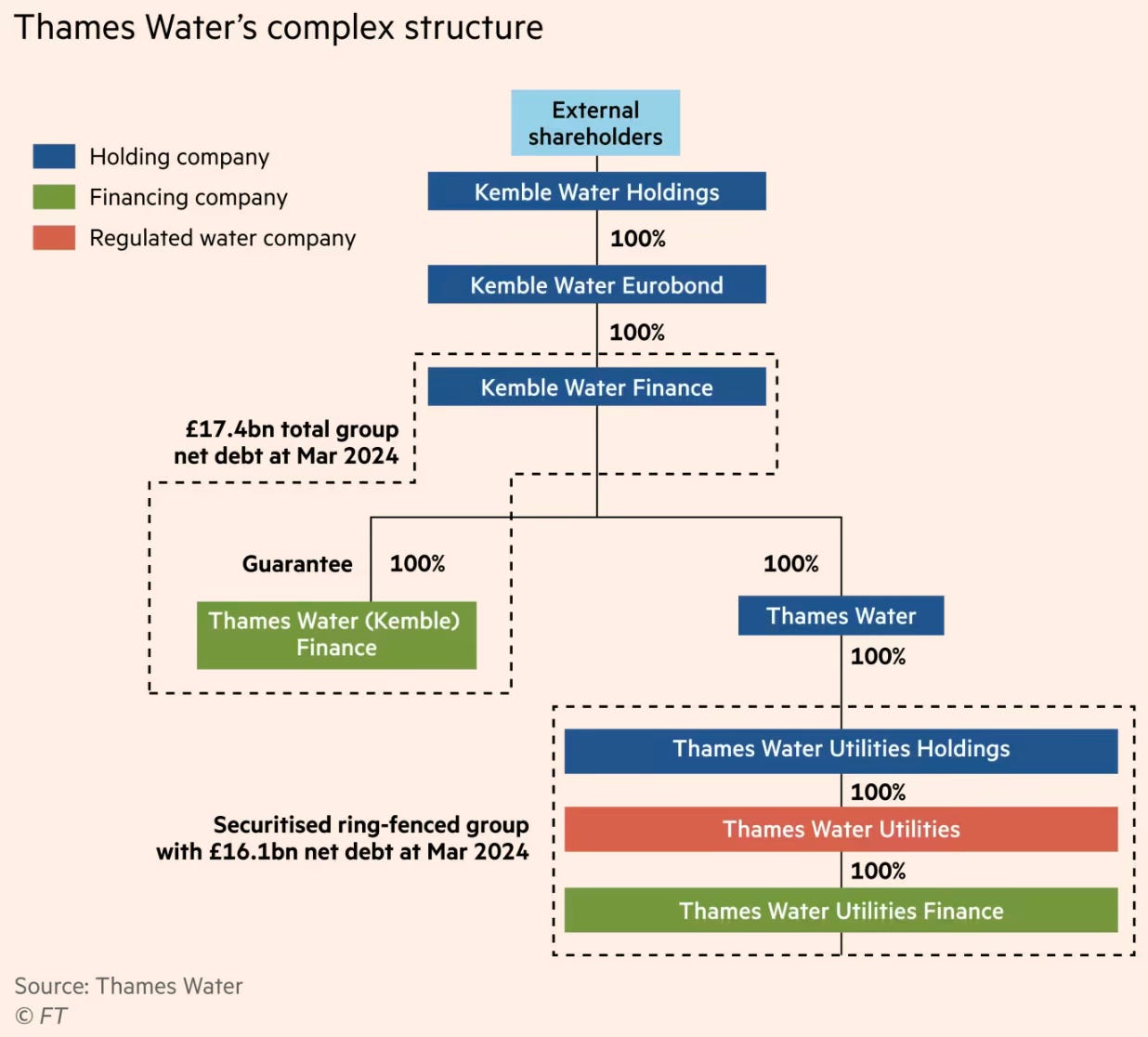

This is the latest update on the Kemble Water Holdings structure.

However, the government approval for the emergency loan proposal has been criticised by Sir Dieter Helm, who believes it’s a case of endless sticking of plasters. He has instead proposed that Thames Water be placed under a Special Administrator to allow a proper restructuring and enable the management to focus on operations instead of financing negotiations.

In a paper explaining his views, Helm makes some very important points that are of relevance not only to the present case but to infrastructure and public-private partnerships in general. He has argued that the emergency loan is not only not going to fix Thames’s problems but also risks spreading the contagion across the rest of the water industry. He writes

Thames will probably get sold at a very steep discount in a process controlled by its A-class bondholders, and will probably get broken up. Yet even if this turns out to be a potentially very profitable opportunity to purchase the business for a deeply discounted value, it does not bode well for Thames’s future. The private interests of the sellers in the short term should not be confused with the public interest that a Special Administrator would pursue… it is important to understand why Thames is not a self-righting ship; why it is unlikely to emerge as an efficient water and sewerage company over the next decade; and why the sticky plasters may serve to gradually undermine it further.

He has blamed the crisis at the Thames on a combination of bad management, bad regulation, and the failings of successive governments. He points to fundamental incentive distortions and perversions that detracted the management from working to realise the objectives of privatisation.

Like all the water companies, Thames was privatised with zero debt (indeed a small cash injection was provided upon privatisation). It (and the other water companies) were privatised in order to run their networks and infrastructures better (bringing private sector cost disciplines) and to raise finance to pay for capital investments on the basis of borrowing so that current customers (and current voters) would not have to pay. The Thames model, like that of the other companies, was pay-when-delivered, not pay-as-you-go.

This gave two tasks to the management of all the companies: run the business more efficiently; and raise finance for capital investment. Thames has turned out not to have done the former very well; and it has used the balance sheet to securitise the business, rather than for the objective at privatisation, which was to borrow solely to invest. In both, it has been at the outer edge of water company performance and gearing… it is worth examining what the incentives have been and why cost-cutting has had priority over capital maintenance. RPI-X as a regulatory rule had the advantage of simplicity at the outset. The regulator would set the (fixed) prices ex ante every five years (originally it was supposed to be every ten), and the companies would maximise profits by minimising costs.

As was witnessed across the privatised utilities, this deceptively simple rule required regulators to be very clear about the outputs that had to be delivered as part of the fixed-price contract, and to make sure that they were actually delivered. In practice, this meant approving the business plan for the period, and having clear, measurable and enforceable environmental and social outcomes. Thames (and others) ran rings around the regulators, and provoked a process of regulatory creep with ever-more complex and detailed interventions by the regulators, which even ended up regulating Thames’s dividends. As a rough rule of thumb, regulators added at least two new mechanisms at each periodic review. The added complexity did not result in greater performance improvements…

The governments, OFWAT, the NRA/EA and the companies all implicitly worked on the basis of an approach that started with what they thought customers could afford and then agreed what could be done for these amounts, rather than starting with the environmental and other outcomes required, and then setting charges at whatever it costs to achieve them efficiently. This is the origin of a context in which a blind eye was turned to environmental failures, and the fines were so low as to be part of the cost of doing business. This affordability criterion has undoubtedly curtailed environmental improvements. All this went under the guise of the quadripartite process in the early periodic reviews… As ever, there is a mismatch between, on the one hand, the demands for higher river and water quality, and, on the other hand, the opposition to bills being raised to pay for these. The belated and relatively sudden imposition of large fines reflects this change of tone. Thames and others could have reasonably assumed that the “implicit deal” around affordability would let them off the hook. What their successive boards failed to realise is that the licence gave them the obligations, and relying on politicians and regulators being objective, rather than following public opinion and media coverage, was always a dangerous strategy to pursue.

He also writes about the egregious operational failings of Thames Water, resulting in the normalisation of untreated sewerage spillages into rivers, asset mapping of its networks, and lagging behind in the adoption of digital technologies to improve maintenance. The biggest failing was its financial engineering and asset stripping, second only to the regulatory failure to spot and prevent it.

What makes Thames more of a basket case than the others is that, in addition to failing on the capital maintenance, it was profit-maximising by gearing up its balance sheet at the outer limits of what was sustainable. This turned out to be the most profitable activity of the company. Whereas the balance sheet had been set up at privatisation to move from pay-as-you-go to pay-when-delivered, Thames (and others) used the balance sheet to mortgage the assets and pay out the proceeds in special dividends and other benefits to the shareholders. All the companies were doing this, but Thames pushed it further (though not as far as, for example, Heathrow Airport, at 95% gearing).

The reason that this model was so profitable was the combination of very poor regulation and extremely low interest rates. OFWAT is the stand-out case of the failure to protect the balance sheets for the purposes they were intended (although OFGEM has neglected balance sheets too). Indeed, OFWAT stressed the importance of leaving matters pertaining to the capital structure and the balance sheets to the companies. OFWAT sets the cost of capital using the CAPM (capital asset pricing model) and then applies a WACC (weighted average cost of capital) to set the allowed returns. The WACC is an average of the costs of debt and the costs of equity. By definition, it will over-reward debt and under-reward equity – before any other consideration is applied to the tax and other impacts. Hence the simple opportunity: replace equity with debt by mortgaging the assets.

Thames took this to a whole new scale, engaging in whole-company securitisation and creating an offshore set of companies to facilitate this, going under the label of various Kemble entities. It was brilliantly executed, building on a strategy that had its origins back in the mid-1990s when OFWAT (and OFGEM’s predecessors: OFFER and OFGAS) decided not to act to protect the balance sheets… the owners… were simply exploiting the opportunities placed in front of them. OFWAT belatedly recognised the mistake of ignoring gearing and balance sheets, and went so far as to give indications about the sorts of gearing it might like, yet at no point did it run proper pro-forma balance sheets from privatisation setting the gearing against investments not paid for by current customers.

The upshot of this combination of failures – failure by Thames to run itself efficiently; failure by Thames to do the necessary capital maintenance; failure by Thames to understand its assets; failure by OFWAT to get a grip on the balance sheets and prevent the huge scale of financial engineering; failure by the NRA and then the EA to properly enforce environmental standards and performance; failure by governments, OFWAT and Thames to ensure that the periodic reviews provided sufficient revenues through customers’ bills; and failure by Thames to appeal against the OFWAT periodic review determinations – is the sorry mess that Thames now finds itself in.

Further, an investigation by the Office for Environmental Protection has revealed regulatory failure and excessive leniency on sewage spillage by the water companies during normal times by three authorities in the UK - the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; the Environment Agency; and the Water Services Regulation Authority, which is known as Ofwat.

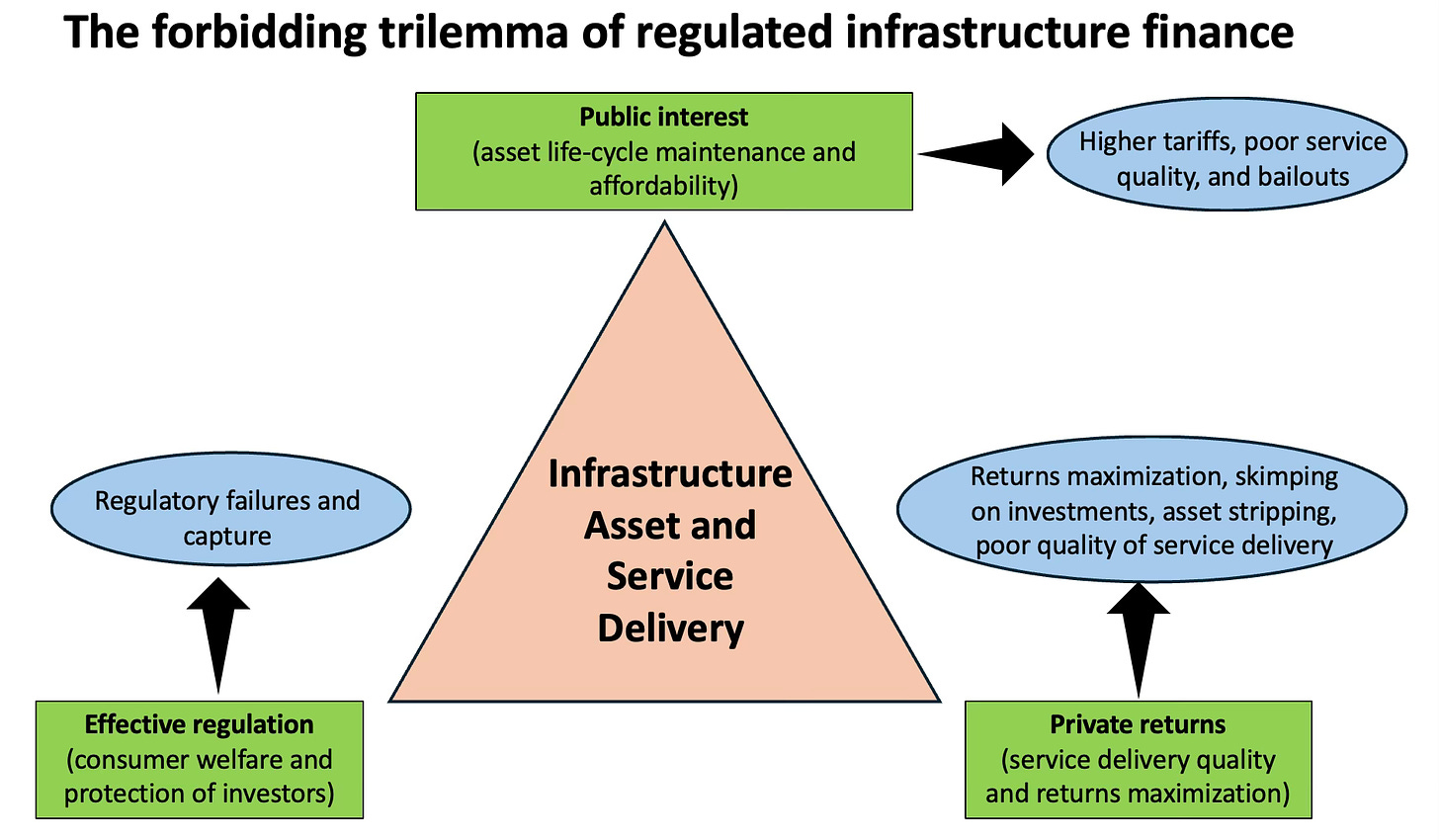

The Thames Water example is an illustration of three forbidding challenges with private investments in infrastructure - the political economy of ensuring the affordability of service delivery; the incentive compatibility of investors in balancing life-cycle asset management and quality of service delivery (public interest) with maximising their financial returns (private interest); and the capability of regulators in reconciling the interests of consumers and investors.

In the real world, politicians always face the pressure of keeping a lid on prices/tariffs and generally succumb to it; investors cannot but not subordinate all else to returns maximisation; and regulators fail to keep their eye on their primary objectives, struggle to keep up with the changing practices/trends of the industry, and end up being captured by the regulated.

Taken together, there’s a forbidding trilemma in infrastructure privatisation and PPPs. Private investments in infrastructure struggle when faced with managing public interest, private returns, and effective regulation! It’s very hard to meet all three challenges simultaneously.

In fact, it boils down to the fundamental and unbridgeable tension between affordability of service delivery and returns maximisation. This challenge becomes daunting with investors like private equity whose returns maximisation objectives fundamentally conflict with infrastructure assets' risk and returns profile.

None of this should be taken to mean that we should avoid private investments in infrastructure. Instead, it’s a note of caution on the daunting challenges of making private investments work in real-world contexts.

Given the political economy, private incentives, and weak and/or vulnerable regulatory capabilities, private investments in infrastructure must be intermediated by simple financing structures, contracts with simple and easily observed outcomes, and an acknowledgement of the real costs of capital maintenance and service delivery. Among investors, it must also be incentivised by lower return expectations (or stability and portfolio diversification objectives).

No comments:

Post a Comment