I have blogged on several occasions on the topic of affordable housing. They all have a common theme: the role of urban planning in promoting or inhibiting the supply of affordable housing units. In this series, I have blogged about some examples globally where upzoning reforms have increased the supply of affordable housing. They include widespread upzoning in Zurich, Sao Paulo, and Auckland, which have substantially impacted housing supply.

In this context, Matthew Maltman and Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy have a paper that discusses zoning reforms enacted in Lower Hutt, a small municipality in the Wellington metropolitan region of New Zealand, since the late 2010s, to enable medium- and high-density housing in residential areas.

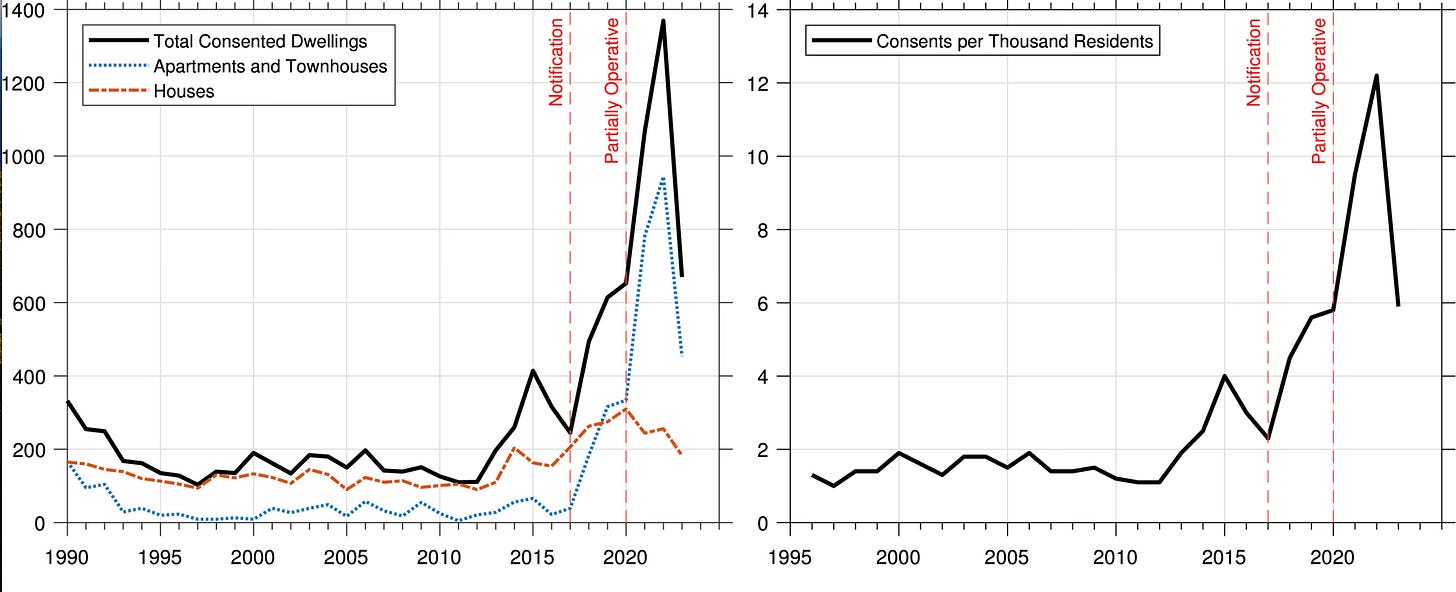

Beginning in the late 2010s, Lower Hutt began a sequence of widespread zoning changes to encourage housing supply that culminated in approximately 80% of residential land being upzoned to support high or medium density housing… Using a synthetic control to specify the policy counterfactual, we find that these zoning changes generated a three-fold increase in consents per capita and nearly tripled the number of housing starts over the six years subsequent to the onset of the reforms. Depending on how potential displacement effects are accounted for, the Lower Hutt reforms increased housing starts across the wider metropolitan region by approximately 10 to 18%. We also present evidence that the upzonings reduced rents by around 21% relative to the counterfactual outcome six years after reform…

Despite being home to approximately one-in-four residents, Lower Hutt accounted for only 13% of all new dwelling consents across the region over the ten years prior to the first medium density zoning change. Subsequent to that upzoning becoming operational, the city accounts for 36% (the plurality) of all starts… Our findings add to the growing body of evidence that zoning regulations can significantly restrict housing supply, and that easing those restrictions to allow for medium- and high- density housing can have a substantial positive impact on housing construction, and ultimately affordability… Widespread zoning reform can be a powerful policy tool to stimulate housing supply.

The upzoning reforms were remarkable since it was initiated by the Hutt City Council (and not part of any top-down mandate), were widespread (impacting 80% of residential zoned land), and eased restrictions on both dwelling density (like minimum lot size) and floor space (site coverage and height maximums).

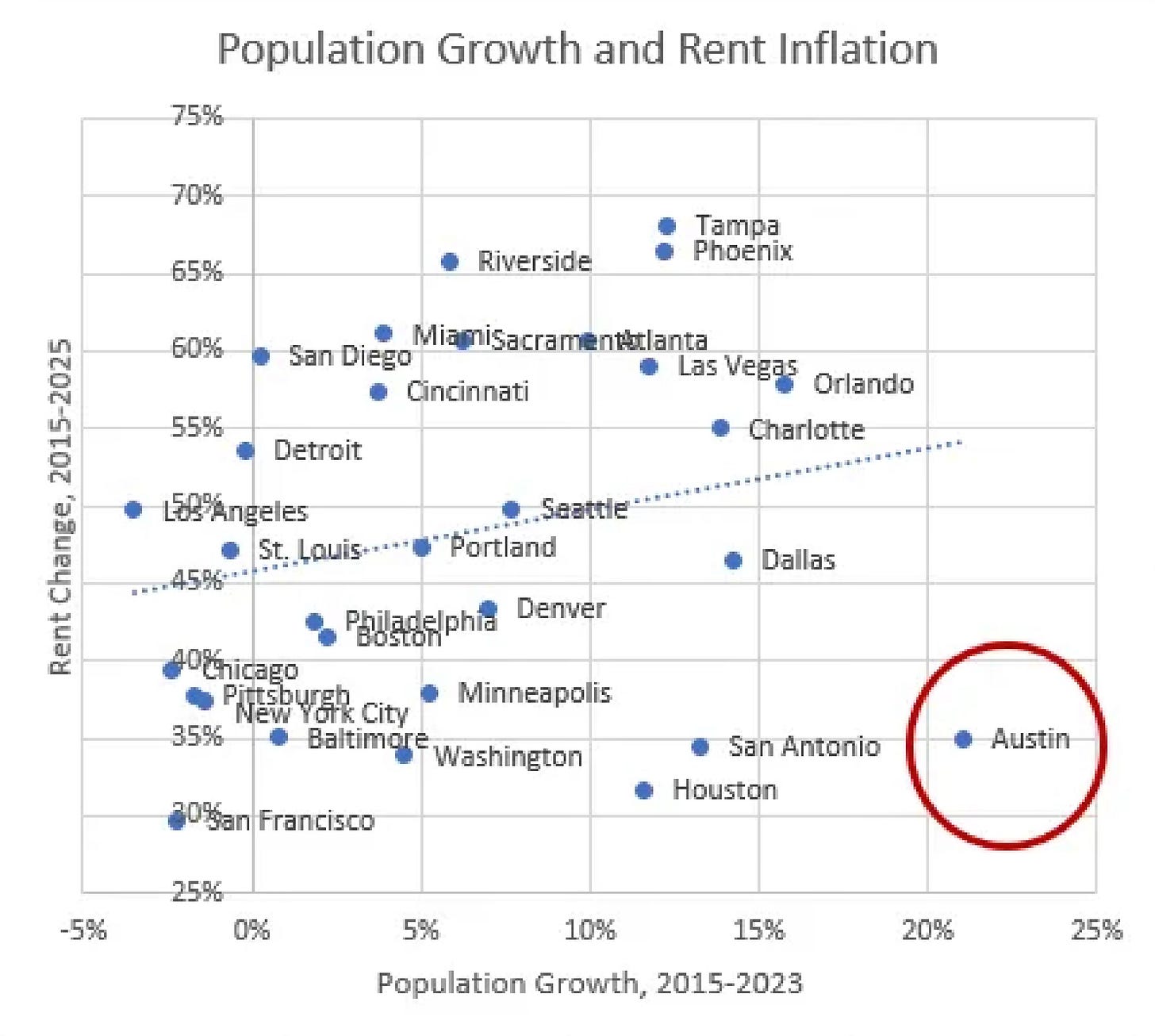

Perhaps the most famous example from the US of the positive impact of liberalised zoning regulations is Texas. Four of its cities have had the highest population growth among US cities, but have also managed to keep rent changes low.

A major contributor is the state’s policy on financing and governance of greenfield developments. Its special-purpose Municipal Utility District (MUD) allow developers to create greenfield communities by funding infrastructure with “future” residents’ taxes. It builds on a history of independent local districts (since 1890s) that have been used to address water, irrigation, and flood control needs. Since the mid-20th century, MUDs were first adopted by developers in Houston to develop new communities fuelled by the oil boom, and have since spread across Texas. This is a good description of MUDs.

At its core, a Municipal Utility District is a small government entity created to fund and provide basic infrastructure in an area where city services don’t exist. The genius of the model is how these services are financed: developers front the costs, and *future* homeowners repay those costs over time via property taxes and utility fees… the MUD model aligns the timing of costs and benefits: developers build first, get paid later; homeowners buy homes, pay later for the infrastructure through taxes; and cities get growth without upfront expense or risk… A developer or landowner with a large parcel (often empty land) petitions the state to create a new MUD for that area. This petition either goes through a special law passed by the Texas Legislature or to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). If a MUD is within an ETJ, they have to agree to let the MUD take it, and usually do so with some standards to which the infrastructure should be built, expecting to annex the MUD in the future… founding your MUD… can be done with as few as two people as residents to form the board… This establishes the MUD as a legitimate elected body over the area…

Now that the MUD is founded, the developer builds out the infrastructure. They build water lines and sewer systems (often drilling wells and erecting treatment plants if not connecting to a city), drainage ponds, streets and sidewalks, fire stations, street lights, and sometimes parks and playgrounds. All of this is done with the developer’s own capital or private financing. Essentially, the developer is acting like the “city,” constructing the backbone that homeowners need… the MUD will reimburse the developer by issuing tax-exempt bonds after enough homes are built. Now that they’ve spent big on the infrastructure, the developer is in a race to build and sell as many homes as they can in as short of a time period as possible… The MUD helps the developer sell these homes with a low sticker price, because the cost of the infrastructure supporting them is not included in the home price, but rather will be collected by the MUD via it’s authority to tax residents.

TCEQ has guidelines that say that a MUD can’t issue any bonds until 25% of the value of planned homes has been built and assessed. They also have to show that the tax burden on future residents is reasonable, which usually is achieved at around the 40% occupancy rate. After meeting the requirements and getting approval from TCEQ and the Texas Attorney General, the MUD will issue municipal bonds on the public market to raise funds. These bonds are backed by the MUDs right to tax residents and are therefore quite a safe investment, they are also tax-free! So lots of people buy these bonds, and the money goes to reimburse the developer for fronting the capital in the first place. By paying out on the bonds, new homeowners gradually pay off the infrastructure over 20–30 years instead of having those costs loaded into the upfront price of the home. Once the bonds are paid out, the tax rate generally drops to cover maintenance costs… A MUD will continue to exist until and unless the city annexes the area and takes over services and the MUD is dissolved.

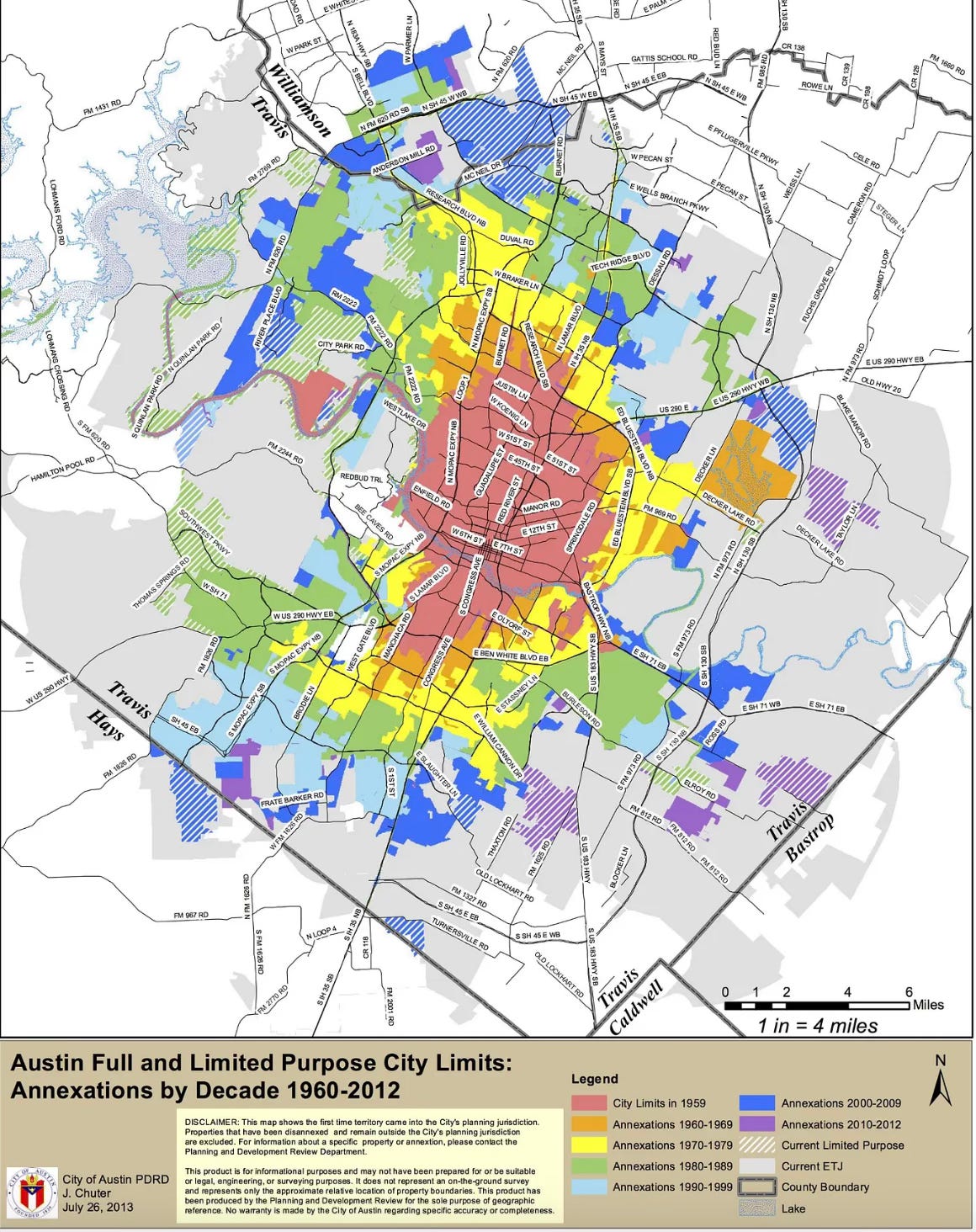

The growth of MUDs was facilitated by local conditions - weak Texas county governments with limited authority and revenues in unincorporated suburban areas, the reluctance of cities to extend utilities into their extraterritorial jurisdictions (ETJs) due to cost or risk, and the presence of large tracts of undeveloped lands just outside city limits. Texas currently have over 950 MUDs, and over time they join or are annexed by the local municipalities. This is important.

Texas cities frequently annex developed MUD areas decades after growth occurs (Houston annexed Kingwood, Clear Lake, etc.), but notably MUDs enabled the growth to happen in the first place – growth might never have occurred if it had waited on city financing or approval.

MUDs are essentially an institutional mechanism to mobilise upfront finance to build housing. In order to address the emergence of sprawls, it should be considered to maximise densified developments in these new developments. They should also be encouraged to become mixed-use facilities. Finally, MUDs should be integrated with the regional master plans.

The governance of MUDs is critical and has the potential to tar the idea itself. In a context of weak governance, the MUDs can become an outlet for fly-by-night developers to create MUDs, develop layouts, sell houses, raise debt, siphon funds, recover their investments and also make a handsome profit. This possibility must be kept in mind while allowing for MUDs.

While all the examples in this blog have been about liberalisation of zoning regulations in terms of densification, The Times has a long read that makes a counter-intuitive case for a return to sprawl, or edge-city development, in the US to increase supply.

The sprawl had become a lightning road for urban growth in the US since the mid-20th century, with critics blaming it for consuming farmland, eating up commute times and spewing pollution, and creating vast tracts of ghastly and isolated monocultures. It provoked anti-sprawl policies across the US on land-use and environmental protection. The article argues that these laws have increased the cost of construction and reduced supply, creating an affordable housing crisis across the country. It’s estimated that there’s a shortage of 4-8 million housing units.

The article points to a 1979 book, ‘The Environmental Protection Hustle’, by a MIT Professor of Urban Planning, Bernard Frieden, to highlight a major problem created by these anti-sprawl laws.

Because most of today’s suburbs were built after zoning and land-use laws became more widespread and stringent, it has been harder to fill in the closest suburbs with density the way older cities did. This has increased the pressure to grow outward. Since 1950, big American cities have added very little new housing in established neighborhoods, according to an analysis by Issi Romem, an economist at MetroSight, an economic research and consulting firm. It might not seem that way when you look out on the glass-tower apartments and condominiums that have risen in the downtowns of big and even midsize U.S. cities. But those projects are frequently part of an industrial redevelopment, like Mission Bay in San Francisco or Hudson Yards in New York. They rarely disrupt neighborhoods zoned for single-family homes, which account for a majority of the land mass in many U.S. metro areas. California and other states have spent much of the past decade trying to get out of this predicament by undoing single-family zoning laws and streamlining permitting for apartments, backyard cottages and other higher-density housing.

The impact of liberalised zoning regulations is felt in the aggregate and over time, and it’s very large. Sample this about how the state of Texas has become the primary driver of housing supply in the US.

Much of the nation’s housing growth has moved to states in the South and Southwest, where a surplus of open land and willingness to sprawl has turned the Sun Belt into a kind of national sponge that sops up housing demand from higher-cost cities. The largest metro areas there have about 20 percent of the nation’s population, but over the past five years they have built 42 percent of the nation’s new single-family homes, according to a recent report by Cullum Clark, an economist at the George W. Bush Institute, a research center in Dallas… In the past five years, the Dallas metro area has led the nation in both population and housing growth. Last year alone, Dallas permitted the construction of 72,000 new homes, or about three-quarters as many as the entire state of California, according to Moody’s Analytics.

Texas is also a great illustration of how markets respond to incentives in terms of liberalised regulations in an acutely supply-constrained market.

Celina, Tex., was recently declared the fastest-growing city in the country. The area had 8,000 residents a decade ago. Now it has 54,000, and the population is projected to hit 110,000 by 2030. Nearby, Hillwood is building a community called Ramble, which is scheduled to offer 4,000 new homes starting next year.

But such rapid growth also brings its set of problems

There were just two stoplights in Princeton, Tex., when Eugene Escobar Jr. moved there. That was a dozen years ago, back when Princeton was a town of fewer than 10,000 that sat beyond Dallas but wasn’t yet part of it. The subdivisions had started arriving, but a good amount of the housing still consisted of faded homes with clapboard siding and chain-link fences. Escobar, a 33-year-old from Harlem… recently became the city’s first Black mayor, in an election dominated by debates over runaway growth. Since Escobar arrived, the population of Princeton has quintupled to just under 50,000 residents, according to city estimates, overwhelming the roads, the sewers and the local Police Department. Now the nation’s third-fastest-growing city, Princeton has become a case study in what happens when development outpaces planning…

Despite the boom in residents, Princeton still has just a handful of restaurants and few places to take children beyond private backyards. There are not many local jobs, so most of Princeton’s residents commute out of town for work. The largest employer is the local government. “We went from a farm town to a city of 47,000, and in the next three years it will be 80,000,” Escobar said. “The city allowed a lot of developers to come in and was looking at the tax money but didn’t realize, ‘Hey, the water is behind, the police are behind.’” Last year, the City Council voted to impose a moratorium on all new housing projects in hopes of giving infrastructure time to catch up… Residents, having bought into what they thought was a bright future, are now worried about where the city is headed.

But such messy problems should not constrain cities from growth. This is a very apt description of the messy process of urban growth

Princeton’s godawful traffic and its views of pastures being consumed by tract homes are exactly the sorts of scenes opponents of sprawl have in their heads. But this is how cities are built: through a chaotic and uneven process in which the mix of homes, jobs and infrastructure is constantly shifting and never quite in balance. Instead of endless sprawl, it’s better to think of boomtowns like Princeton as economic nodes in a broader region. Their relationship to Dallas proper is akin to Newark’s relationship to New York or Oakland’s to San Francisco: They begin as satellites of the core city but, over time, become their own cores.

That process is well underway in Texas: As the population of Dallas’s northern region has exploded, jobs have followed. Plano and Frisco, two Dallas suburbs that have each surpassed 200,000 residents, are rapidly adding offices and apartment buildings and have daytime populations that roughly equal or exceed their nighttime populations, becoming cities in their own right. Modern, car-centric cities will probably never become as dense as places whose streets were designed for pedestrians, but the basic process of expanding outward with housing, then jobs, is unchanged. Over the decades, places like Plano and Frisco will come to look and feel more like central Dallas. “Sprawl is a way of thinking that is centered on the core city, that imagines somehow that people, however far out their homes are, they’re going to commute to the core,” says Clark, of the George W. Bush Institute. “That’s increasingly unmoored from the reality of how people are living.”

This article illustrates the importance of outward greenfield growth to complement densified growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment