This blog has long argued that India has an aggregate demand problem (see this), and this requires creating more productive jobs and broad-basing economic growth to achieve sustained high growth rates.

Paraphrasing Paul Krugman on productivity, it can just as easily be said that while economic growth is not everything, in the long run, it’s almost everything. See also this. As developing countries face onslaughts on multiple fronts to their comparative advantages, it’s an appropriate time to reflect on economic growth.

Even since economic development became a topic of interest, it has been accepted that developing countries have a comparative advantage in their lower cost of production, arising from not just cheap labour, but also weaker regulations of economic actors, their activities, and their contexts. The eighty years since the war may be regarded as the high noon of development, as it lifted billions out of poverty and brought unprecedented economic, social, and political progress. An important contributor was trade liberalisation and globalisation, which allowed lower-income countries to leverage their comparative advantages to pursue export-led growth strategies.

Thanks to the China problem, climate change, and now Donald Trump, all these comparative advantages have not only become liabilities but have become targets of punitive actions. For example, given his single-minded focus on trade deficit and the reflex to conduct trade policy in public glare with the single instrument of tariffs, it can be safely argued that as long as Donald Trump is the President, he’s unlikely to allow India’s trade surplus with the US to grow significantly. With external markets becoming increasingly hostile, in varying degrees, and the trend likely to become a new norm, developing countries are being forced to look inward for their new growth drivers.

In this context, it may now be time for countries like India to focus on their domestic markets, specifically in terms of creating productive jobs and the rising tide of economic growth lifting all boats, if they are to achieve and sustain high growth rates for long periods. Trade, while useful, is likely to be a secondary contributor, unlike during the period of the East Asian economic miracle, which included China and, more recently, Vietnam.

A well-known feature of the trajectory of economic development is structural transformation, where economies shift resources (land, labour, and capital) from agriculture to manufacturing and services, and from less productive to more productive activities. I shall not dwell on this here.

Instead, I’ll focus in this post on another, less-discussed feature of the trajectory of economic development, the role of cost arbitrage in its various forms. This involves firms paying lower wages, having fewer regulations and lower compliance costs (or weaker enforcement), and minimising taxes (by keeping at least some activities informal), while serving highly differentiated and price-sensitive markets. It’s complemented by good-quality public goods provided by governments at no or marginal cost. In general, development is characterised by an increasing cost of production.

In econspeak, firms can externalise a significant share of their costs to be borne by society and the government. All this allows them to sell at low enough prices that are affordable to the predominantly low-income consumers in these countries. Not only does this dynamic create jobs and sustain growth, but over time, productivity increases, wages rise, and consumption expands at the extensive (more quantity of products) and intensive (greater quality and differentiation of products) margins. It ought to create a rising share of consumers who are less price sensitive and inclined to quality and premium goods and services.

Firms benefit from the emergence of this growing share of higher-income consumption class that can afford differentiated and premium products that generate higher margins. This provides them with the resources and incentives to invest in productivity improvements and innovations, and generally assume more risks. It also allows them to keep margins and prices low for their mass market products and solutions.

While I don’t know of studies on this, there are compelling reasons to argue that in the Indian context, this growth dynamic is seriously impeded.

The country may be going too fast and too far on the formalisation pathway. It may be trying to move faster on climate change than its economic foundations would allow. The country’s high consumption class may be too small (see also this) to allow firms to innovate and/or offer premium quality products.

I have written here arguing that formalisation imposes costs that cascade across the economy (lowering profits, wages, investments, and job creation), and that formalisation happens less by converting the informal sector but by expanding the formal sector (new activities start as informal). I have written here arguing that climate change adaptation and mitigation also impose prohibitive costs that will be serious impediments to economic growth. I have also written here, highlighting that India’s overwhelming majority of low-income consumers are deeply price sensitive and have very low baseline incomes, and its higher-income consumption class is too small to be able to allow firms to generate the resources required to innovate and take risks.

Factor costs, too, may be inflated compared to, say, the East Asian economies, at their similar stages of growth. Land values across urban centres are prohibitive and pose a major barrier to business formation and expansion. Outside of the big firms, Indian enterprises face a very high cost of capital. India’s bank credit to the private sector as a share of GDP is among the lowest for any major economy. While labour is plentiful, the problems are with quality and location. Since good jobs are located in the larger urban agglomerations where the cost of living (especially housing) has become exorbitant, skilled labour demands more for relocation than what the firms can afford. Echoing this, some have written that we may be having a wages crisis.

The combination of indirect and direct taxes, coupled with fees at the state and local government levels, means that firms across many sectors face a high net tax burden. The revenue bias of taxation policies and their enforcement does not help. Input costs are higher compared to their EM peers. For example, electricity distribution companies find firms and commercial services a convenient channel to cross-subsidise their lower-tariff household consumers.

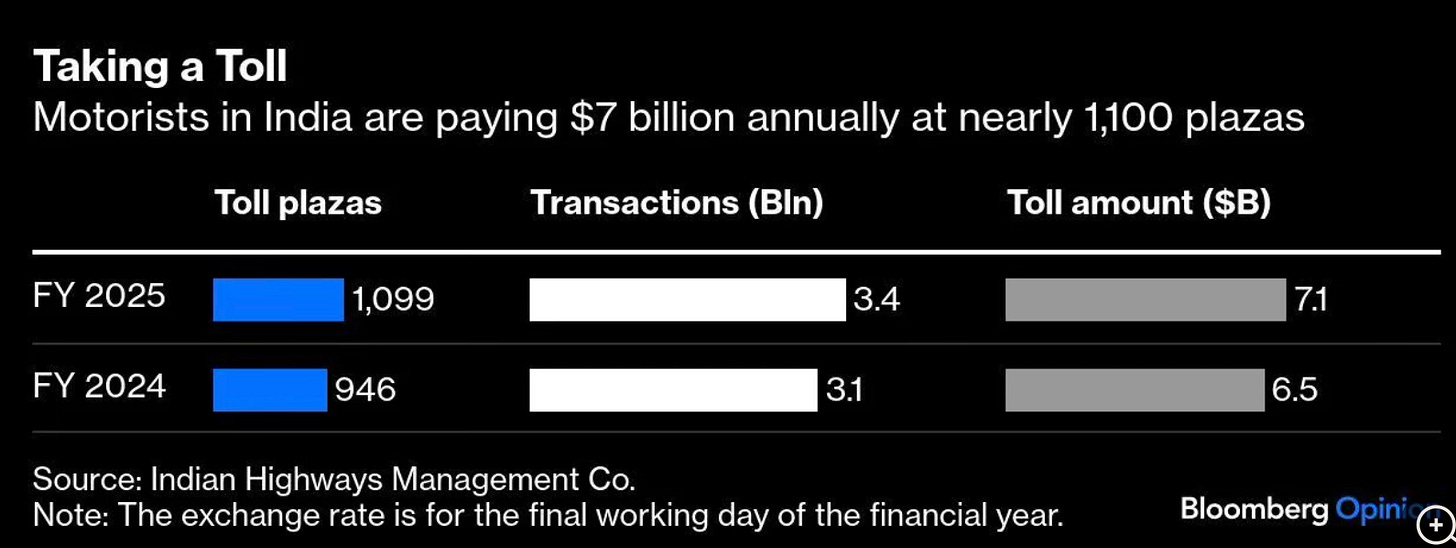

The extensive use of private finance for the delivery of public goods may have raised costs more than the economy can bear. Andy Mukherjee points to the problems with burdening India’s small, car-owning middle class with tolls that add a prohibitive cost to car users.

A still-small, car-owning middle class (fewer than one in 10 households) is feeling squeezed by the $7 billion it pays in tolls every year. The National Highway Authority, which racked up more than $40 billion in debt, is deleveraging. It’s selling assets to private operators and investment trusts; it’s also securitizing a part of its portfolio. But no matter who owns them, debt financing means roads still have to generate revenue. The burden on motorists will only swell as new highways get constructed.

The US confronted the debt-financing problem well before President Dwight Eisenhower started the interstate highway program in 1956. Toll Roads and Free Roads, a 1939 report prepared for Congress, rejected the usage-fee option as revenue from traffic in many places wouldn’t be enough to retire the bonds needed to back them. So the funding came from the government, which taxes motorists on gasoline and diesel… However, Indian motorists are paying 30% more for fuel than the average American. Then there is the vehicle itself. The auto industry complains that hefty taxes have put cars in the same category as drugs or alcohol. Half the cost of a new SUV is tax. It isn’t hard to see why consumers are unhappy.

It’s useful to bear in mind that the $7 billion is an additional cost paid by consumers and businesses just for their logistics. This is in addition to the already high fuel prices that are heavily taxed by the central and state governments.

There’s a compelling case that all these factors combine to significantly increase the costs faced by firms in India and erode their competitiveness. In other words, given the small high-consumption class, the Indian economy may have a cost structure comparable to that of a developed economy with the aggregate demand of a low-income country. This squeezes businesses from both the supply and demand sides and limits their flexibility to pursue standard business models.

This aspect must be explored and discussed to figure out the extent to which it’s a binding constraint on growth. It has important implications for public policy and business decisions.

None of the above should be construed as an argument against formalisation, digitalisation, PPPs, etc. Instead, it’s only a note of caution to be cognisant of a real problem in terms of the cost structures coupled with the aggregate demand constraint that may be binding on the Indian economy.

India’s automobile market offers useful insights in this regard. A feature of this market, highlighted in several news reports in recent times, has been the stagnation in the two-wheeler and small car markets on the one side and the relative growth in the market for Sport Utility Vehicles (SUVs). The problems are nicely captured in a Business Standard article

While the middle class is increasingly unable to transition from two-wheelers to entry-level cars, the sport utility vehicle (SUV) segment is recording a rising share of first-time buyers… Regulatory changes — including tighter safety and emission norms —have pushed up car prices, while salaries have largely stagnated. A Maruti Celerio that sold for ₹2.8-4.4 lakh in 2016 now costs between ₹5.6 lakh and ₹6.7 lakh. Unsurprisingly, many buyers are turning to the used car market, which has been growing at a double-digit pace over the past two-three years…with small cars and sedans accounting for the bulk of the sales… India’s used car market, growing at 10–12 per cent annually, is projected to hit $40 billion by FY26… Shantanu Rooj, founder and CEO of TeamLease Edtech, said fresher salaries have been stagnant for 5–7 years, mostly hovering between ₹2 lakh and ₹4 lakh annually. With annual pay hikes of just 5–7 per cent, many young earners are struggling to keep pace with inflation. Furthermore, jobs are concentrated in a few major cities, meaning those who relocate often have less disposable income, Rooj said.

The article points to the observations of Mr RC Bhargava, the Chairman of Maruti Suzuki, the country’s largest automaker, who has argued that only 12% of the households that earn over Rs 12 lakh per year can afford a car priced above Rs 10 lakh.

For Bhargava, the solution lies in making small cars more affordable. “That requires lower taxes and a reduction in the cost of regulations,” he had said… the rising regulatory cost — such as the mandate to include six airbags in cars — and high taxes as a reason for small cars being priced out of the market… tax them at 29-31 per cent (including surcharge)… Indeed, today, there is no small car priced below ₹3 lakh, with on-road starting prices touching ₹4 lakh… The link between GDP growth and PV sales is weakening. From 1999-2000 to 2009-2010, GDP grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.3 per cent, while PV sales grew at 10.3 per cent. Between 2010-2011 and 2019-2020, GDP CAGR rose slightly to 6.6 per cent, but PV sales slowed to 3.6 per cent. In FY25, PV sales grew just 2 per cent, even as GDP expanded by 6.5 per cent.

A senior industry executive noted a troubling trend. India has 213 million two-wheelers on the road, of which 100 million were sold in the past 5–7 years. “There are at least 113 million two-wheelers which are older than that and the owner can consider an upgrade. However, we don’t see these buyers in the market. The first buy for a two-wheeler upgrader is almost always a small car,” the executive explained. He cited data from People Research on India’s Consumer Economy, which showed that in households earning up to ₹7 lakh annually, car penetration fell from 13.9 per cent in FY16 to 9.4 per cent in FY20, while two-wheeler ownership rose from 57 per cent to 66.3 per cent. The composition of the PV market has shifted accordingly, with SUVs and multi-purpose vehicles now accounting for 65 per cent of sales… A senior company executive attributed the shift to changing aspirations and easier access to vehicle finance.

As this editorial in Business Standard writes, businesses have responded to India’s market structure with various jugaad.

The airline industry, which operates on wafer-thin margins, mastered the art of low-cost fares and dynamic pricing to expand a market that was traditionally considered premium. Makers of consumer goods learnt that smaller packs (such as shampoo sachets) or additional value (iodised salt) could bring in lower-income consumers, who would otherwise avoid such products. Per-second billing and bundled handsets changed the dynamics of mobile telephony.

I’m not sure such jugaad can surmount the constraints arising from a predominantly low-income consumption market with a small share of higher-income consumers, the low margins faced by Indian companies, and the relatively high-cost structure of the Indian market.

In summary, four big takeaways are especially relevant to India. One, the potential of exports as a driver of economic growth has shrunk significantly in recent months compared to what was available to the East Asian economies. Two, countries like India must primarily rely on their internal markets to drive economic growth. Three, such growth can be sustained at high rates only if it creates good, productive jobs and is broad-based, such that it creates the critical mass of higher-income consumers to support a growth cascade. Four, apart from the other factors, such growth may be constrained by the high cost structure of the Indian economy and the low baseline of higher-margin sales.

No comments:

Post a Comment