I had been thinking of posting on this for some time. There’s now enough evidence to suggest that the middle class globally is feeling squeezed.

Tej Parikh has an excellent graphics-filled article on the problems being faced by the middle class in developed countries. Middle-class incomes have stagnated, their numbers have reduced, and inflation has worsened matters.

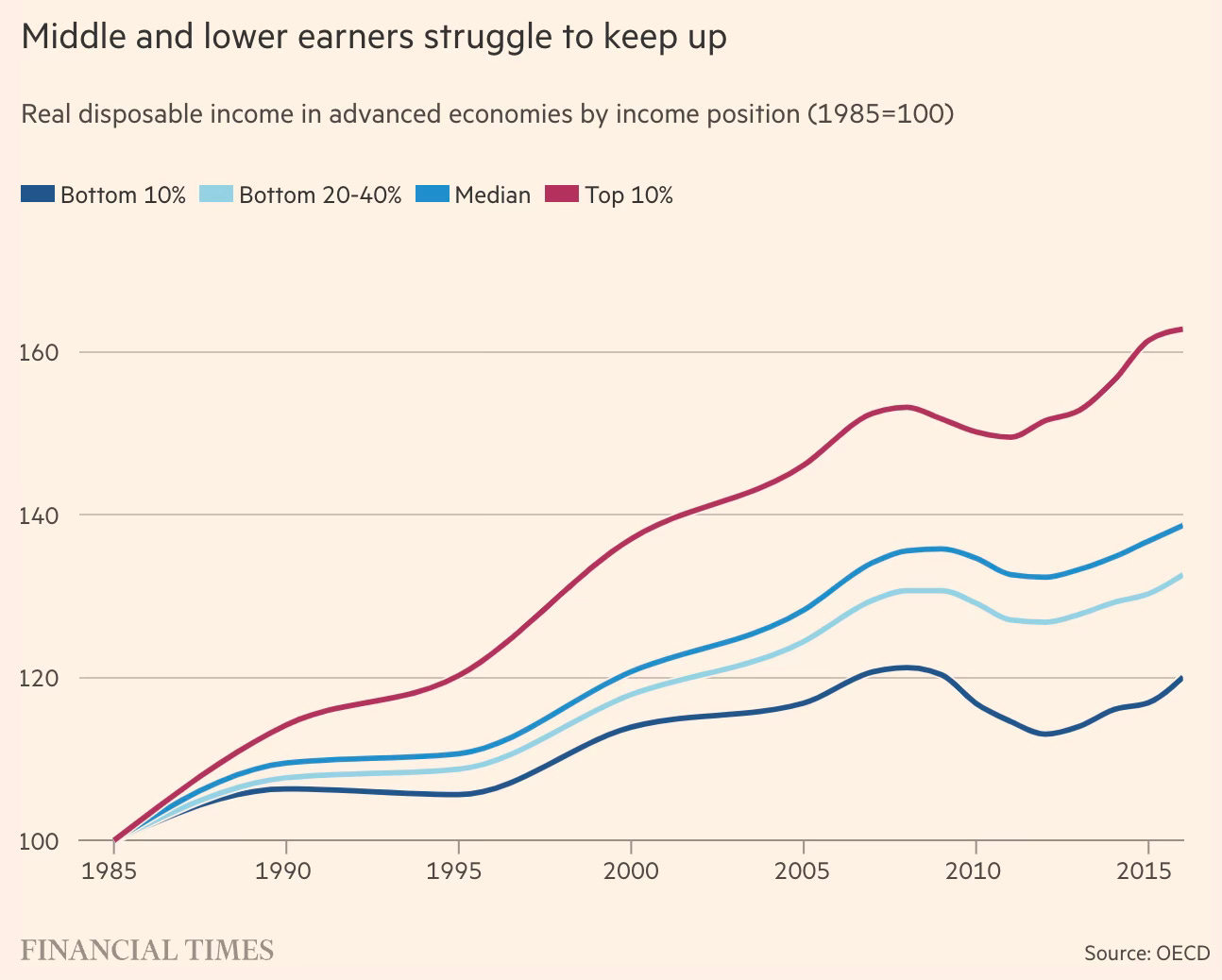

While real incomes at the top have risen, those at the middle and lower ends have stagnated since the financial crisis.

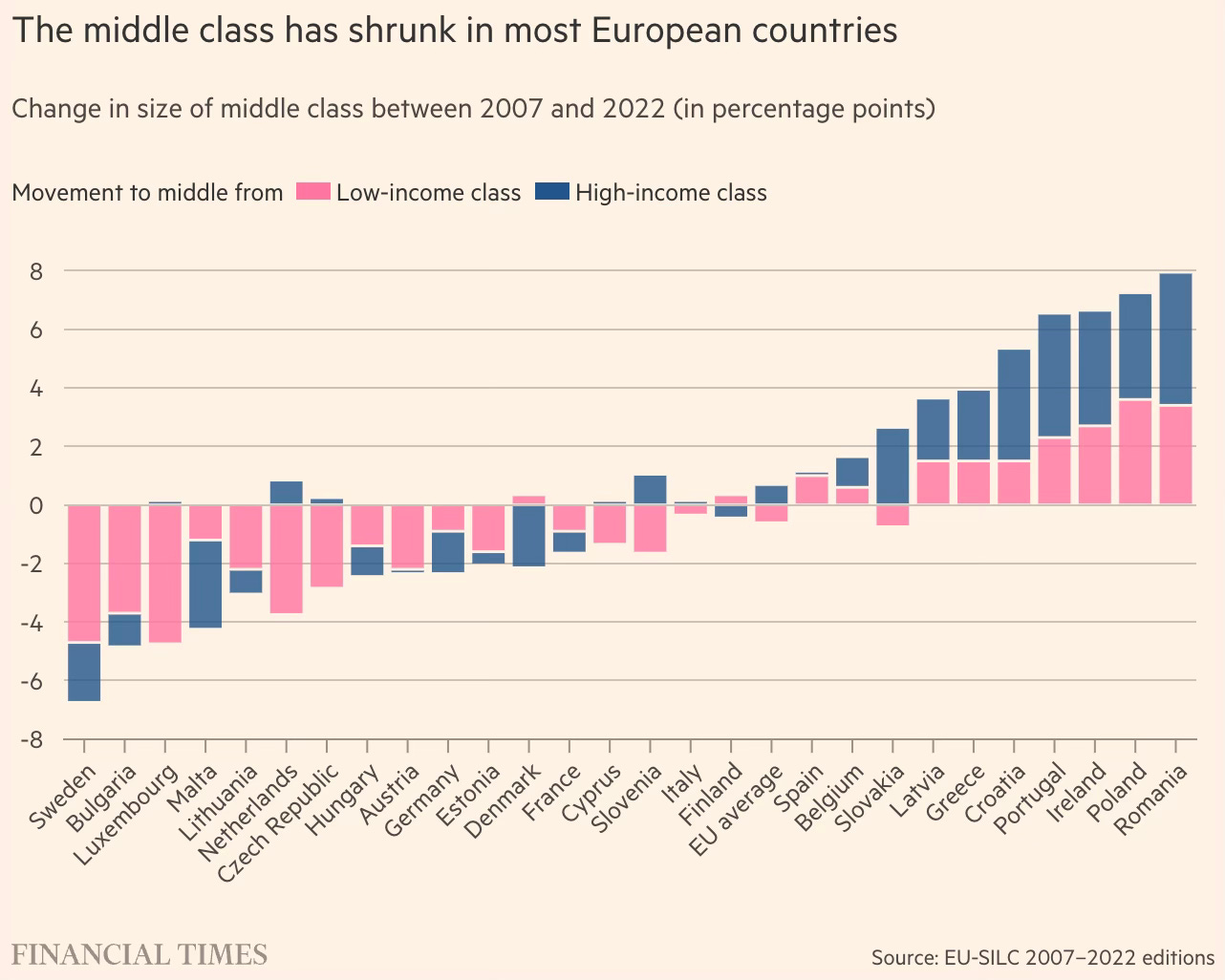

The result is that the middle class has shrunk in many countries.

Inflation has been a major contributor. Here’s from the UK on how wage growth has lagged behind inflation.

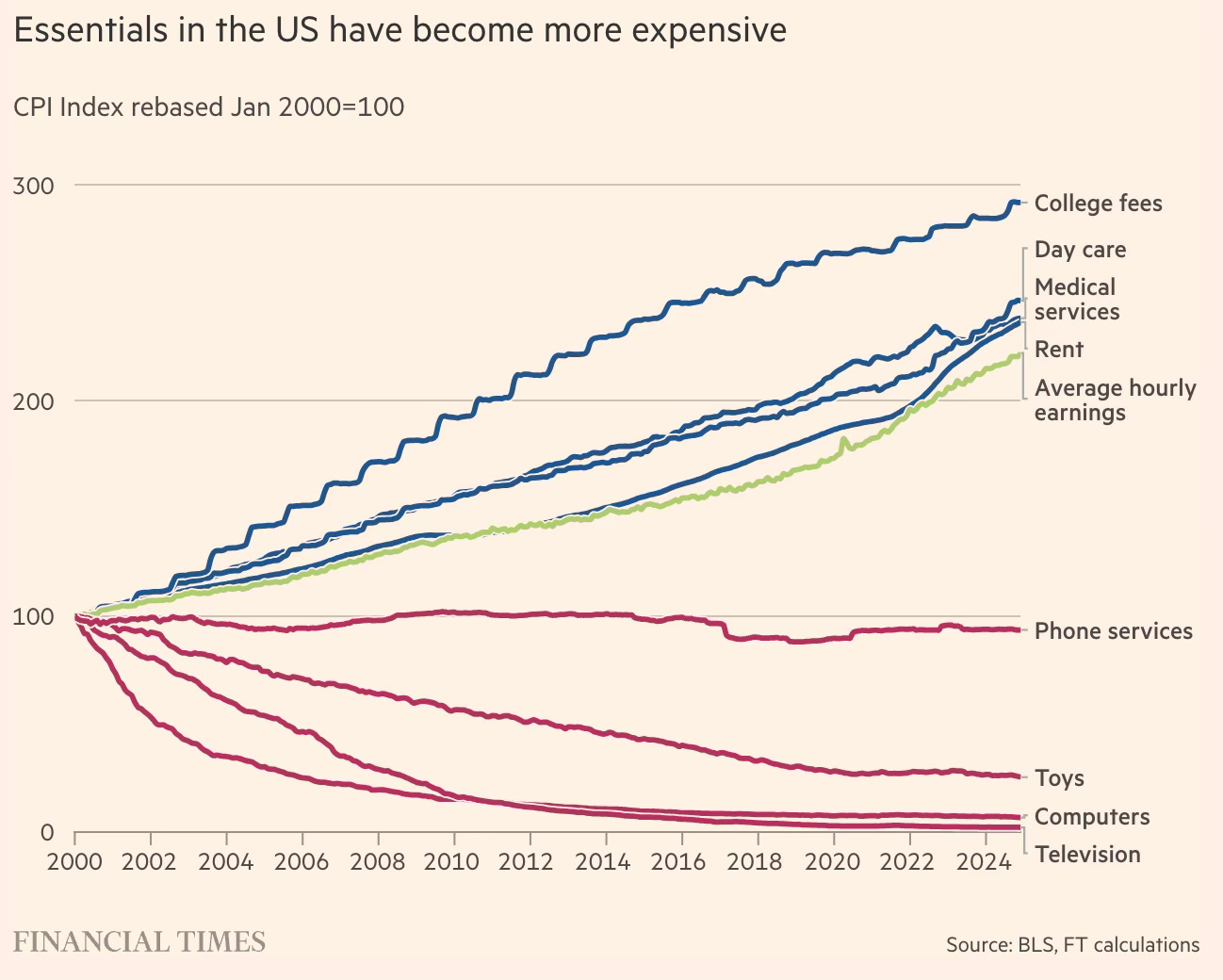

And below from the US, points out that while lower prices of tradeable products have held back inflation, rising costs of non-tradeable essential services have more than offset them.

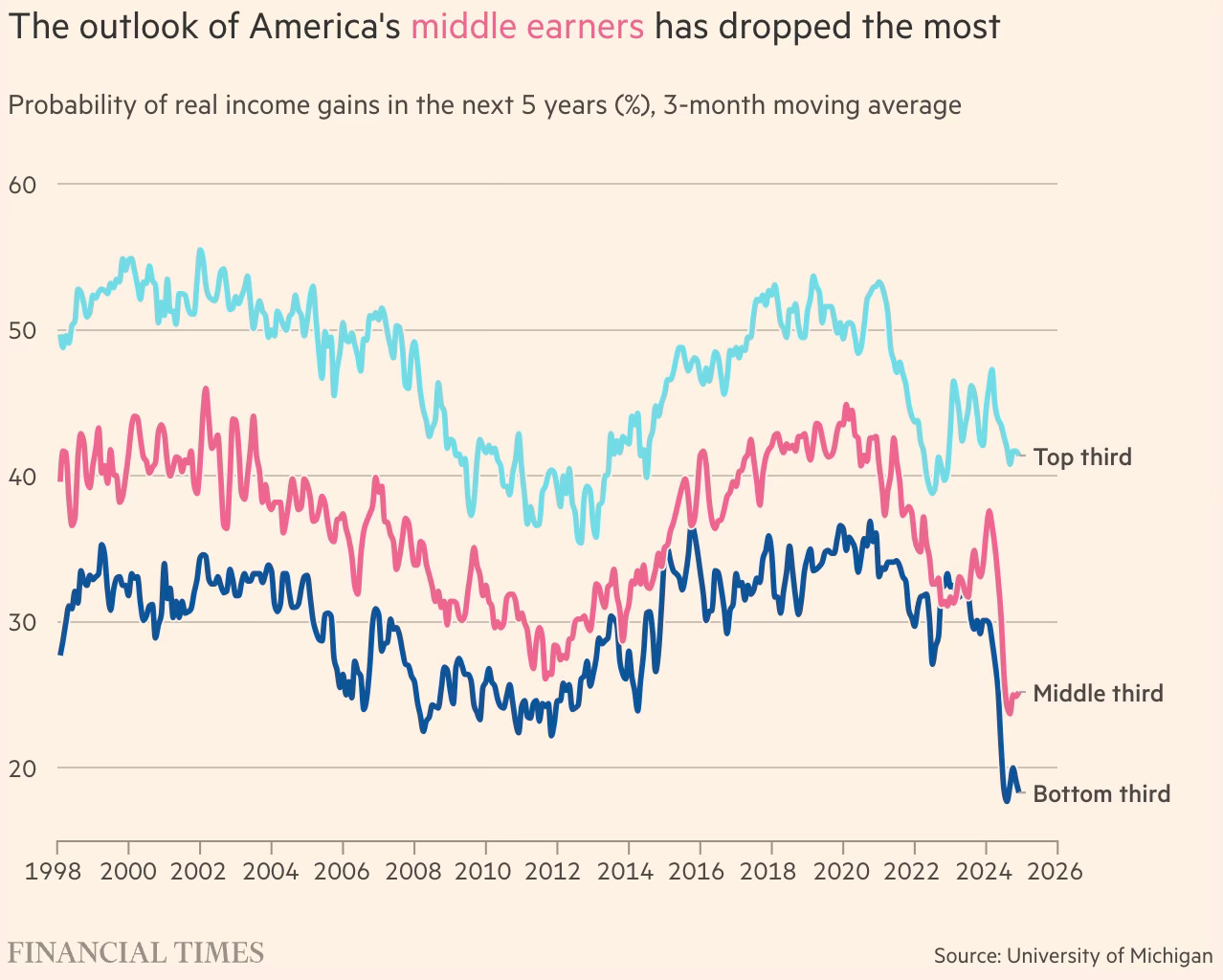

And all this is translating to a middle-class pessimism.

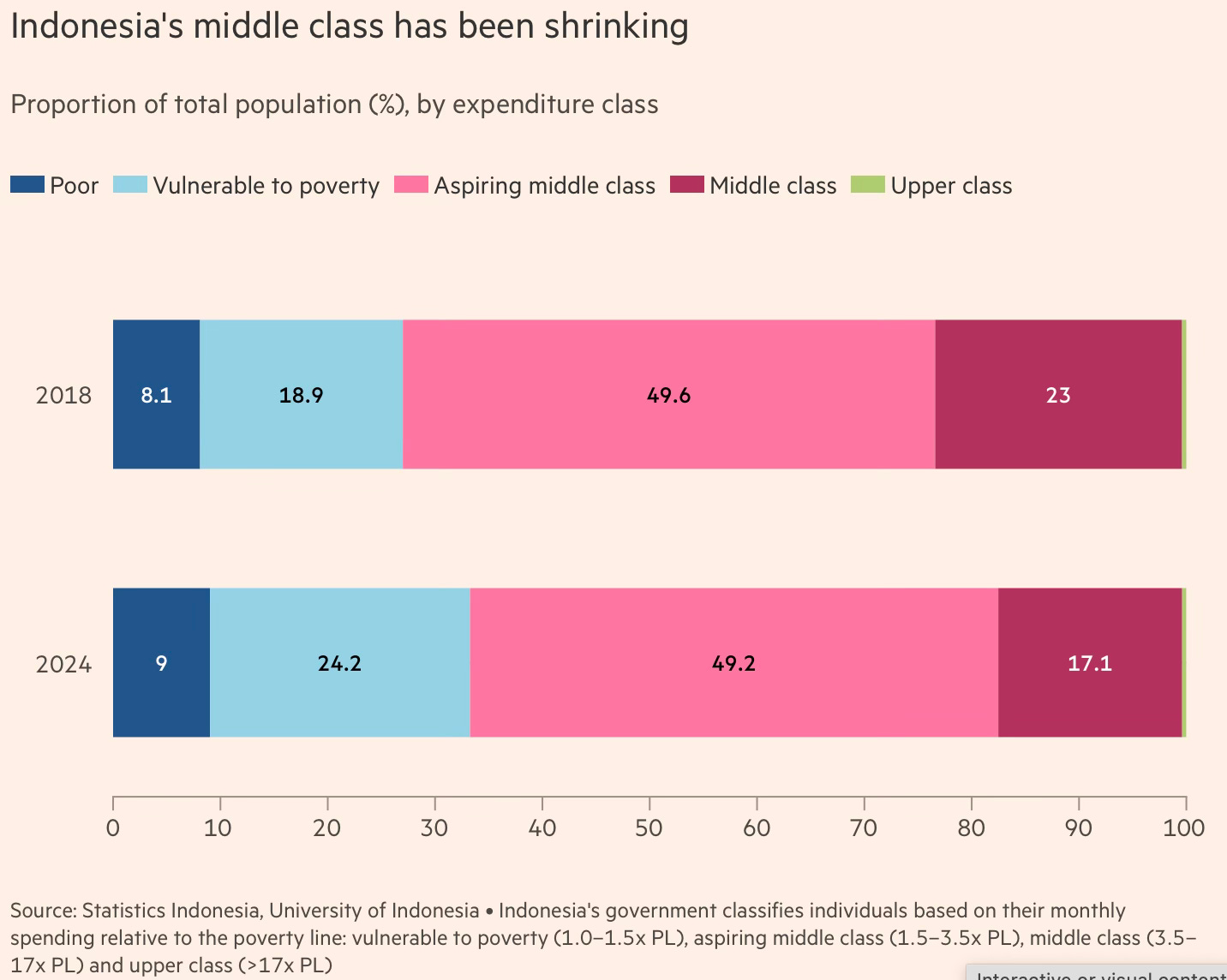

The trend of middle class woes goes beyond developed countries. Another article pointed to the case of Indonesia where middle class (monthly income of $122-605) fell from 47.9 m in March 2024 from 60 m in 2018, down from 23% of the population to 17%.

See also this on Indonesia’s stock market which fell sharply early this week on the back of fears weakening purchasing power, consumer confidence, and economic growth.

The middle-class squeeze is being felt in India too. India’s fundamental economic problem of a narrow consumption baseis compounded by an economy which is not creating the number of good jobs required to quickly expand the middle-class base to support sustained high growth rates. As I blogged here, the vast majority of job creation is in gig work and the likes of construction, security guards, and housemaids, all of which generate monthly incomes in the range of Rs 15000-20000 and have limited productivity improvement opportunities and occupational mobility.

See this about the shrinkage of the Indian middle class during the pandemic and this about the small size of its middle class. The problem is amplified by the acutely deficient dynamism in India’s corporate sector, the low level of R&D investments, and rising business concentration.

A matter of great concern at the good jobs creation side is the growing share of non-regular workers. The ASI data tells us that in the 2001-02 to 2022-23 period, while the number of workers in formal manufacturing more than doubled from 5.96 m to 14.61 m, the share of contract workers rose from 21.8% to 40.7%. In Bihar, 68.6% of the industrial workforce is contractual, compared to 23.8% in Kerala. Capital-intensive industries have had a greater increase in the share of contractual workers. The Quarterly Employment Survey data tells us that the share of contract employees in nine major non-farm sectors doubled from 7.8% of total workers in April 2021 to 18.44% in July 2022. Even accounting for the cyclicality in certain industries which necessitate the hiring of contract labour, this level of increase is striking.

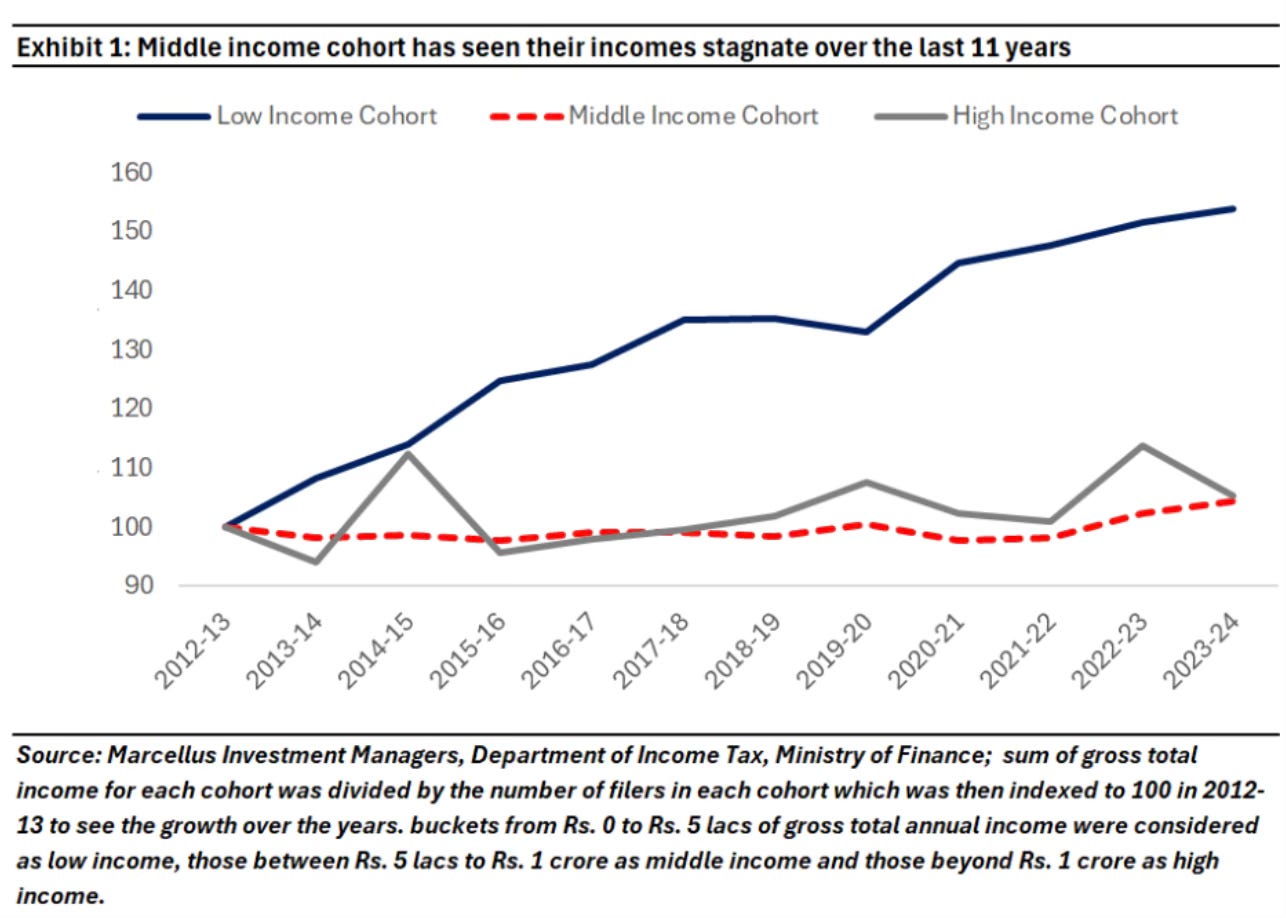

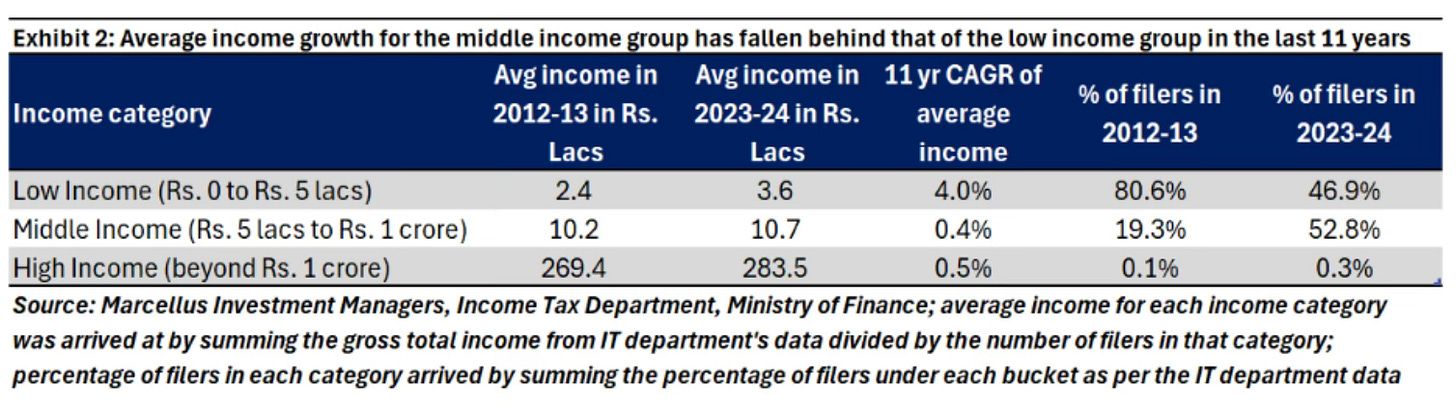

Marcellus Investment Managers provide data that points to stagnant middle-class incomes for more than a decade.

A striking fact presented by them is that the average annual income of the 53% of the taxpayers (2023-24) who filed non-negative tax returns and earns between Rs 5 lakh to Rs 1 Cr per annum have seen their incomes stagnate - average annual income barely moving from Rs 10.23 lakh in 2012-13 to Rs 10.69 lakh in 2023-24!

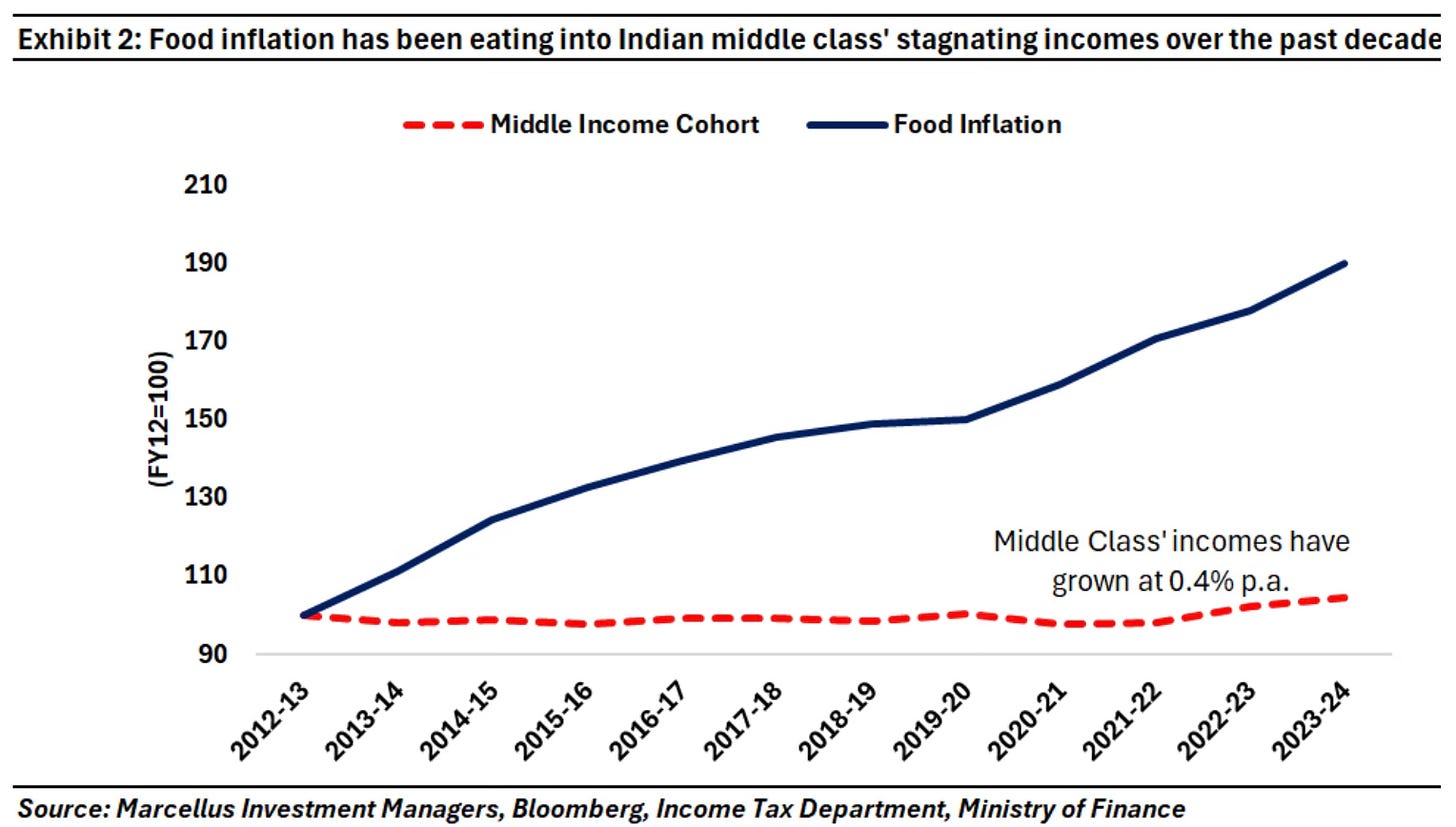

They also point to how inflation has eroded middle class incomes…

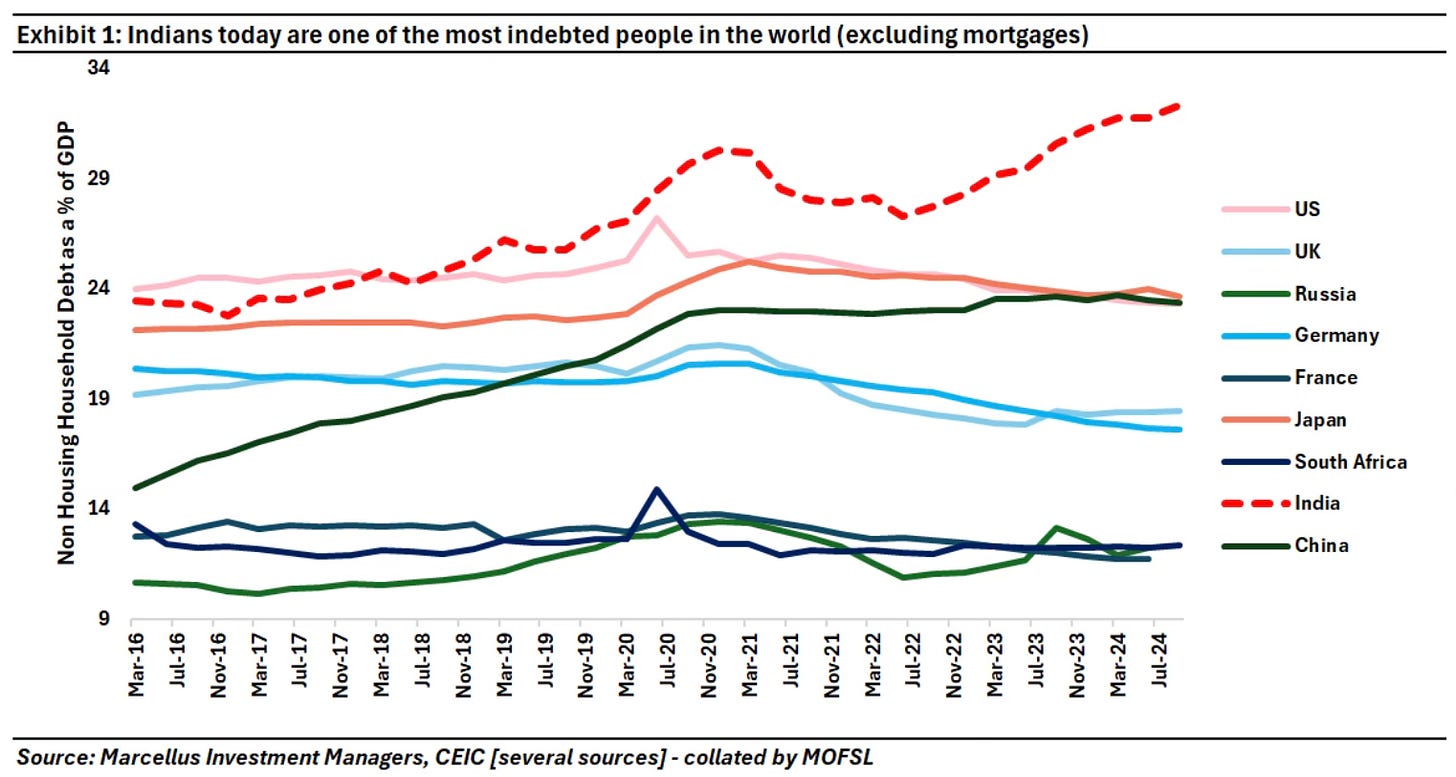

… leading to India having the highest level of household indebtedness if we exclude mortgages.

This is also reflected in the steep decline in the net household financial savings to 5.1% of GDP in 2022-23, the lowest level since 1976, even as gross household savings hold steady at 10-11% of GDP.

The middle-class squeeze is likely to be amplified in the days ahead as automation and AI take hold. One of the most disturbing possibilities is that AI models will virtually eliminate the basic coding jobs that have been an important source of middle-class entry for the Indian workforce. In this context, the new version of Agentic AI has the potential to be even more disruptive.

AI agents, often referred to as ‘Agentic AI’ systems, are models capable of making decisions and taking actions to achieve specific goals without human intervention, making them truly autonomous. Think of a driverless car that adapts to traffic conditions, a smart home assistant that learns your habits, or an AI-driven financial bot that analyses market trends and makes stock trades. Other examples include AI-powered automation in finance and healthcare, policy claims processing, and software development. The distinction between a non-agentic and an agentic system lies in the level of autonomy and decision-making capabilities. For instance, a non-agentic workflow will respond only to specific inputs or commands, follow pre-defined rules and procedures, and need constant human intervention for most decision-making.

A basic chatbot, for instance, will only respond with pre-programmed, scripted answers to specific questions. An agentic workflow, on the other hand, can initiate actions and take its own decisions… AI agents also learn continuously, refining responses and actions over time, as seen with Uniphore, which improves customer service by analysing call interactions. Unlike large language model-based chatbots, agentic AI integrates with business software such as customer relationship management (CRM) and enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems and handles multi-step workflows such as processing insurance claims or automating supply chains… This means that AI agentic systems go beyond chatbots by autonomously making decisions and executing tasks.

The trends in advanced economies, Indonesia, and India point to the same three aspects of middle-class discontent - scarcity in the creation of good jobs, stagnant wage growth, and erosion of purchasing power.

Globally, good jobs are being displaced by automation and lower-paying temporary jobs. In the US, David Autor and others have pointed to the role of automation and cheap imports from China contributing to job losses and a hollowing out of middle-class jobs. I have argued here that cheap Chinese imports should be a bigger source of concern for developing countries (than developed ones) in so far as China is their direct competitor at the lower and middle ends of the manufacturing sector. As Artificial Intelligence (AI) emerges as the general purpose technology (GPT) of our times, another trend unfolding is that of automation and job losses. In their search for efficiency and maximisation of profits, businesses will increasingly adopt AI solutions.

Second, greater returns to capital coupled with weaker bargaining power has led to stagnant labour incomes. High and rising business concentration and financialisation raise the returns to capital at the cost of labour. This, coupled with incentives facing them - stock market expectations, a never-ending cycle of rising executive compensation, and weak labour bargaining power - means that businesses are loath to share profits.

Finally, inflation is eroding incomes. Across the world, globalisation, trade liberalisation, and immigration integrated markets and lowered prices in the tradeable goods and non-tradeable services sectors. But the trend of rising protectionism and anti-immigration are strong headwinds that will start to bind with increasing intensity in future and raise prices. An additional inflationary factor is the compressed timelines on climate change policies. See the latest from Australia on a “cost of living crisis”.

There’s nothing on the horizon that’s likely to counteract these trends. Middle-class discontent will only grow. Any meaningful response must necessarily involve some (or all) of the following

1. In advanced economies, minimum wages must rise to levels that allow for some basic level of dignified life. Notwithstanding inflationary risks, such regulatory wage minimums can have knock-on upward pressures on wages.

2. In both developed and developing countries, the sharing of returns between capital and labour should become more equitable. This will require that labour’s bargaining power be increased through institutional (unions, workplace management councils, etc.) and regulatory measures. At some time in future, broad caps on the salary and compensation ratios across levels becoming a norm cannot be ruled out.

Measures in this regard are most effective when they emerge from internal deliberations and form part of an industry consensus. This requires serious debates in industry forums on this issue that both sensitise all stakeholders on its importance and lead to the emergence of constructive solutions to address it. As an example, benchmarks could be agreed upon, and businesses could be ranked on the equity of their recruitment modes and compensation structures.

3. Gig work is rapidly emerging as the major source of formal sector job creation. It is estimated that there are over 12 million workers employed in the gig economy, and this number is rising rapidly. It poses economy-wide risks to allow such a large workforce to remain without access to basic social safety protections. Since the sector is now de-risked and mature, there’s a case for closing the regulatory arbitrage opportunities essential for its emergence and early growth.

Further, such services cater to the top end of the income ladder, whose demand is unlikely to diminish significantly even with higher costs of service arising from closing the regulatory arbitrage opportunities. It also helps that these services are non-tradeable in nature.

4. The practice of increasing contractual and other non-regular modes of recruitment too should be discouraged. As with wages, it’s most appropriate if there’s an industry consensus on these that creates the right industry-wide incentives to ensure balance on the modes of recruitment. To start with, it might be useful to have some light-touch regulation that provides non-binding guidance on the share of non-regular employment. This information for each company should become public and salient. This could be supplemented with mild incentives to encourage firms.

In the East Asian economies, there are cultural and normative restraints that moderate the undesirable trends on issues like the sharing of profits, executive compensation structures, recruitment modes etc. There’s a danger that corporate India, with its weaker cultural restraints and closer affinities to the US capitalism, could end up imbibing practices arising from the single-minded pursuit of profit and efficiency maximisation. They must be consciously addressed. India could become a global leader in creating consensual industry benchmarks in these areas.

5. Finally, governments must proactively engage with policies that guide the direction of technology adoption and associated changes. Industrial policy should prioritise incentives linked to employment over capital expenditure and production. Labour-intensive sectors should become the focus of industrial policy. Scarce resources should not be wasted on low-labour-intensity sectors like semiconductor fabrication or data centres. The only exception should be as a strategic requirement.

A strategy would be to double down on employment-linked incentives in various forms - internships, apprentices, reduction in EPF and other costs, wage support for new entrants, industrial policy support through employment generation-linked incentives, etc. The PM Internship Program is a good start. The learnings from the apprenticeship scheme should be used to improve its effectiveness and uptake. Existing schemes like reimbursement of EPF contributions should be simplified to facilitate ease of uptake and continue for an extended period.

The implementation of all these is challenging, and its quality is critical, though the difficulties with eliminating leakages should not become an excuse for not doing these. After all, efficiency and effectiveness concerns have not deterred us from pursuing highly questionable schemes and projects with massive capital subsidies.

All these will be effective only if they are complemented with policies that strive to improve human resource quality, lower the cost of capital, and reduce regulatory burdens. A highly ambitious objective for the government would be to discuss, debate, negotiate and arrive at a consensus on a grand compact with the corporate sector on these issues.

As a final note, while bad choices by the government are certain to attract the ire of opinion makers and the electorate, allowing the market to create bad equilibriums in trade, immigration, inequality, and automation does not generate anywhere close to the same level of opprobrium. And counterfactuals of scenarios avoided by government intervention hardly get a mention.

No comments:

Post a Comment