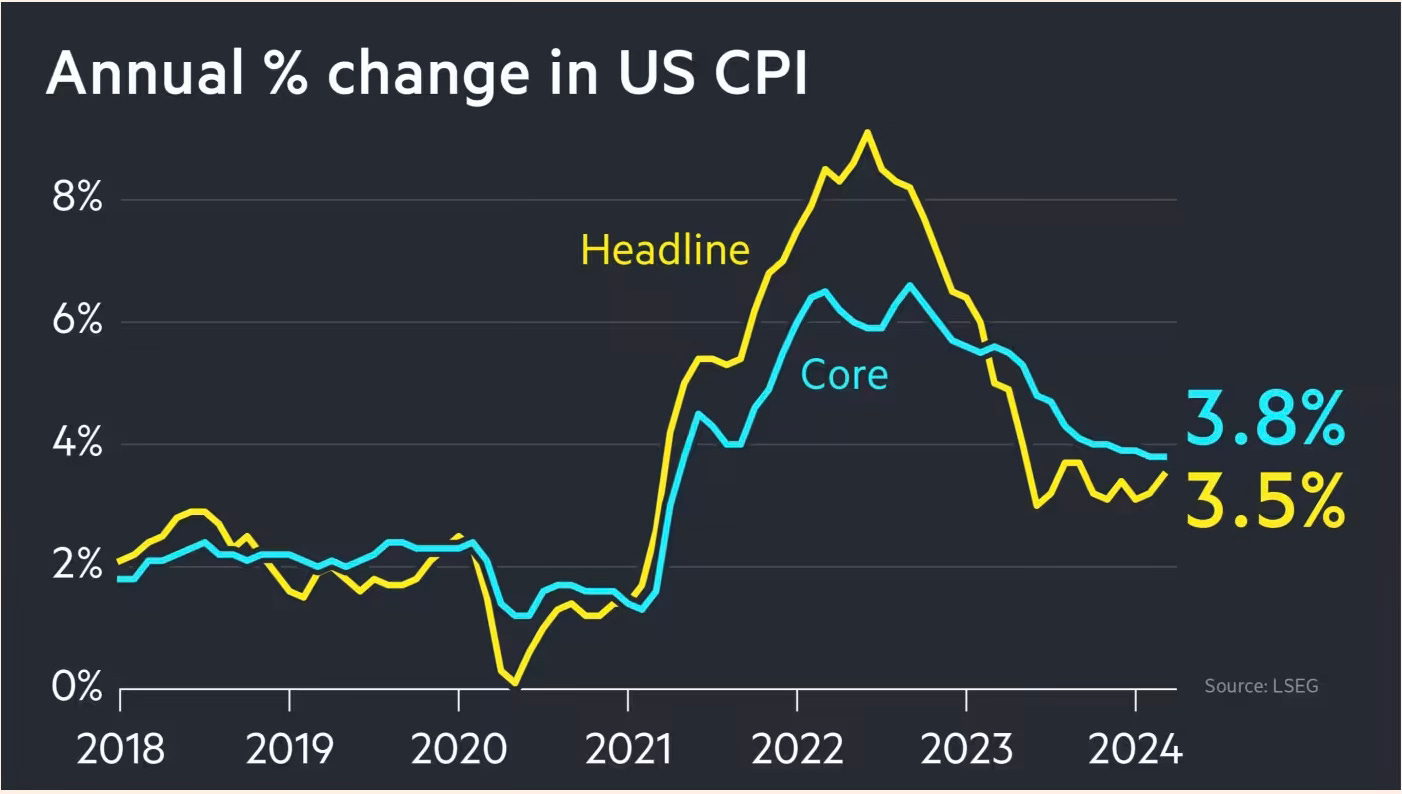

The US consumer price inflation for March came up at 3.5% year-on-year up from February and slightly higher than the forecast of 3.4%. On the same lines core inflation came up at 3.8%, up from the forecast of 3.7%. Bond yields rose and stocks fell as the likelihood of three rate cuts this year starting from June is now very unlikely.

Traders had also previously seen a July cut as a near certainty, but halved their bets on that timing from about 98 per cent to 50 per cent after Wednesday’s report was released. While the markets still give a very high probability to rate cuts by September, they have not fully priced in a cut until the Fed’s November 6-7 meeting... While Fed chair Jay Powell still believes in a “base case” that shows inflation drifting down towards the central bank’s 2 per cent goal, others on the FOMC are increasingly concerned that price pressures will prove stickier than expected. Chicago Fed president Austan Goolsbee has expressed concern that housing inflation will remain too strong, while Dallas chief Lorie Logan has warned of greater “upside risk” to the outlook.

It's to be noted that CPI inflation in the US fell from its peak of 9.06% in June 2022 to 2.97% in June 2023, a fall of 67% in one year. Since then it rose to 3.7% in September 2023 and has remained tightly range-bound between 3-3.5% for the last six months.

Some observations:

1. The impressive lowering of inflation by 67% in a year supports the views of the team transitionary who have argued that the spike in inflation was due to the supply shocks induced first by the pandemic and then by the Russian invasion of Ukraine (and the massive US fiscal stimulus) and once the shocks subside inflation would come down. It’s also true that the decisive action by the central bank helped shape expectations and helped in hastening the reduction of inflation.

2. The recent trends in inflation after June 2023 can be construed to resemble a dead cat bounce. Inflation fell rapidly and now looks like stabilising. The tightly range-bound nature of inflation in the last nine months in the 3-3.7% range testifies to this. It might also be a transition path before inflation again starts to decline to a slightly lower level, say 3%. It’s difficult to foretell the trajectory. However, the assumptions behind competing explanations and theories and the resultant monetary policy actions have critical implications for the economy’s future.

One perspective is to view this as the last mile of the fight to get inflation back to 2%. It can then be argued that the stickiness demands further monetary contraction. The continuing strength of the economy and tightness of the labour market lends credence to the view that the Fed may need to tighten further or at the least wait for the economy to cool further before starting to cut rates. In this perspective, the need of the hour is to either raise rates or wait for the economy to cool before cutting rates. The critical assumption here is the need to get inflation back to 2%.

Another perspective is that the critical assumption itself is wrong and the 2% inflation target, which is a recent invention, is both false precision and unrealistic. If the assumption is wrong, then the policy actions based on it can be very harmful. As I have blogged here, there are compelling reasons to argue that the period of 2% inflation was an aberration and we are now returning to the historic norm of inflation in the 2-4% band. In this view, we are already at the norm and monetary policy should now respond to trends going forward. The worst outcome would be to deploy monetary policy based on the false assumption of the need to get inflation back to 2%. That might end up choking and ushering in a recession due to the limitations of the policymakers (and experts) understanding of the economy.

There’s no way to know ex-ante who’s right and who’s wrong. I’m both inclined against the first and towards the second. Only time will tell who’s right.

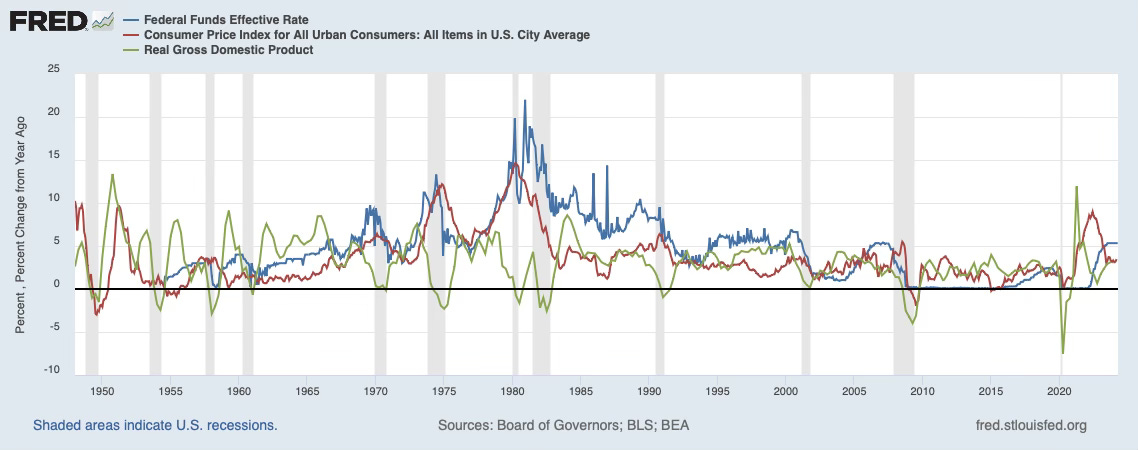

3. It can also be argued that monetary policy in developed countries never returned to normalcy after the global financial crisis. The GFC induced steep interest rate cuts to prop up the financial markets and the economy. Since early 2009, interest rates remained at zero-bound for over seven years. After a brief rise to 2.5%, it was again brought back to zero-bound as the pandemic struck. It was only in April 2022 that the rate hikes started.

From April 2008 to July 2022, or over 15 years at a stretch, interest rates in the US have been 2.5% or below, including at the zero bound for over 9 years. But for a brief spike for some months in 2011 and 2018, from November 2008 till March 2021 inflation too has remained in the 0-2% range. The US stock markets boomed. It was a decade and a half of remarkable economic stability and prosperity. Just compare the period with what preceded it.

The markets and a generation of investors got used to the Goldilocks of low interest rates and low inflation, resulting in a strong economy and labour market and booming equity markets. The myth behind inflation targeting and the 2% inflation target got entrenched during this period. This period also coincided with extraordinary monetary policy measures by the US Fed and other central banks. Quantitative easing, forward guidance, yield control and so on were names given to these policies. Economists and technocrats at central banks started to believe that it was their theories and actions that created this Goldilocks moment in global economic history.

In this context, I cannot but not resist quoting Richard Bernstein’s comparison of the Fed Chairman to a Maytag Repairman,

The Maytag Repairman was a fictional washing machine mechanic who was lonely because no one ever needed to repair a reliable Maytag appliance. Instead of tools, he carried a book of crossword puzzles and cards to play solitaire to combat his boredom. For many years, the US Federal Reserve played the role of the Maytag Repairman with respect to inflation. With the expansion of globalisation and the resulting secular disinflation, there wasn’t much for it to do to fight inflation. Rather, it could generously ease monetary policy during periods of financial market volatility without much concern that its efforts to save investors might spur inflation.

These claims overlook the contributions of peak globalisation, the spectacular long period of growth of China (and to a very limited extent India), the rise of renewable technologies, the spectacular advances in information technology (and the rise of Big Tech), the skill-biased nature of technologies, demographic shifts and global savings glut, geo-political stability, and the extraordinary period of ultra-low interest rates (which drove to the booms in venture capital and private equity models). The world economy experienced an extraordinary confluence of favourable conditions.

It was clear that these tailwinds could not be sustained. Many of them have tapered off and headwinds have arisen starting with the pandemic and now there’s the possibility of a long period of deep geopolitical uncertainties. We are returning to the historical normalcy in the world economy and politics.

It’s therefore reasonable to argue that the Goldilocks period is in the rear-view mirror and inflation will be higher than the 2% target. And the US economy is currently in that range. It will be in the normal inflation territory of 2-4%. Even a cursory look at this graphic will show that US inflation has been above 2% for most of the post-war era. The sub-2% inflation rate has been the exception, not the norm. Monetary policy must respond now based on the emerging inflation trends in the world where normalcy has been restored.

In fact, the IMF itself, as early as 2010, when Olivier Blanchard was the Chief Economist, endorsed a higher inflation target.

A four percent target would ease the constraints on monetary policy arising from the zero bound on interest rates, with the result that economic downturns would be less severe. This benefit would come at minimal cost, because four percent inflation does not harm an economy significantly.

This does not mean that the Fed start cutting rates (since given the new inflation band, the rates are evidently high). Since economic policy is strongly influenced by expectations, it’s also important to consider how the consumers, investors, and markets will react to policy changes given their immediate priors (which continue to be strongly anchored to the Goldilocks world). More importantly, monetary policy has become captive to the financial markets and Wall Street interests. It’s not easy for any Federal Reserve to break out of this capture.

It will take some time before the expectations get adjusted to the new norm and central bankers can free themselves from their masters, and policies can get made based purely on the new normal world. Policy-making must tread carefully in the interregnum. And we are not sure how long it’ll last.

Even if this perspective is wrong, it’s useful for influential policymakers and commentators to consider, introspect, and then make a decision of whether to accept or not. The unknown unknown is the biggest danger.

4. This new world will also mean that valuations in the equity markets will have to be revised downwards. It will upend the business models in areas like private equity. In fact, many parts of financial markets which had become excessively dependent on the ultra-low interest rate environment will face their reckoning when faced with the regime shift in interest rates.

Given how much the economy has become entangled with the fortunes of the financial markets, especially in the US, the revision in valuations will pose a great risk for the economy. More than the economy, this is the most important soft-landing event to look out for in the next couple of years. Will the financial markets be able to adjust to the new normal of interest rates with its attendant downward valuation revisions without too many convulsions? It’s a question on which fortunes of trillions of dollars are riding.

5. In the last four years, many reputed economists like Larry Summers have consistently got everything wrong on inflation and economic growth. One would imagine that they would have learnt some humility. It’s clear from his cheeky remarks quoted in the FT article linked above that the next Fed move might be to raise the rate (instead of any rate cut) that he’s only digging in his heels on his views on inflation.

This is one more reason to argue that the view of people with expertise in non-scientific fields (economics and social sciences) should be taken with caution by policymakers. They are captives of their long-held ideologies and theories, and it takes great courage to step back and break out of the captivity. Rare are those, especially among economists. Angus Deaton is an exception.

Inflation is a wicked problem and you need humility to not be beholden to any grand theory to explain emerging trends. Economists, especially those who have built their reputations defending the orthodoxy, are not well-placed to explain these trends.

6. Finally, putting all the above together, as an explanation of inflation over the last four-odd years, it’s reasonable to argue that the constraints from the consecutive supply shocks spiked prices and once normalcy returned inflation got back to its normal levels (not the pre-pandemic lows). The pandemic and the war provided the much-needed disruption to break out of the long period of low inflation which led to inflationary expectations getting anchored at unrealistically low levels.

Inflation is now back to the range where it has been for most of the post-war era. But given the expectations and the need to gradually reshape them, policymakers must tread cautiously for this and next year to stabilise the new inflation and interest rate regime. Regime shifts are periods of high uncertainty.

No comments:

Post a Comment