I have blogged here and here about the strong likelihood of a general trend of secular decline and stagnation of interest rates. This raises questions about the investment strategies of pension funds, which had taken a big hit from the long period of ultra-low interest rates.

A recent FT article points to multiple interesting links on the issue. A paper by academics from US universities looked at how a typical couple starting to save at 25 can hit three critical targets - amassing as much money as possible for retirement at 65, providing financial security through retirement, and leaving a bequest for the next generation. Their finding:

We challenge two central tenets of lifecycle investing: (i) investors should diversify across stocks and bonds and (ii) the young should hold more stocks than the old. An even mix of 50% domestic stocks and 50% international stocks held throughout one’s lifetime vastly outperforms age-based, stock-bond strategies in building wealth, supporting retirement consumption, preserving capital, and generating bequests. These findings are based on a lifecycle model that features dynamic processes for labor earnings, Social Security benefits, and mortality and captures the salient time-series and cross-sectional properties of long-horizon asset class returns. Given the sheer magnitude of US retirement savings, we estimate that Americans could realize trillions of dollars in welfare gains by adopting the all-equity strategy.

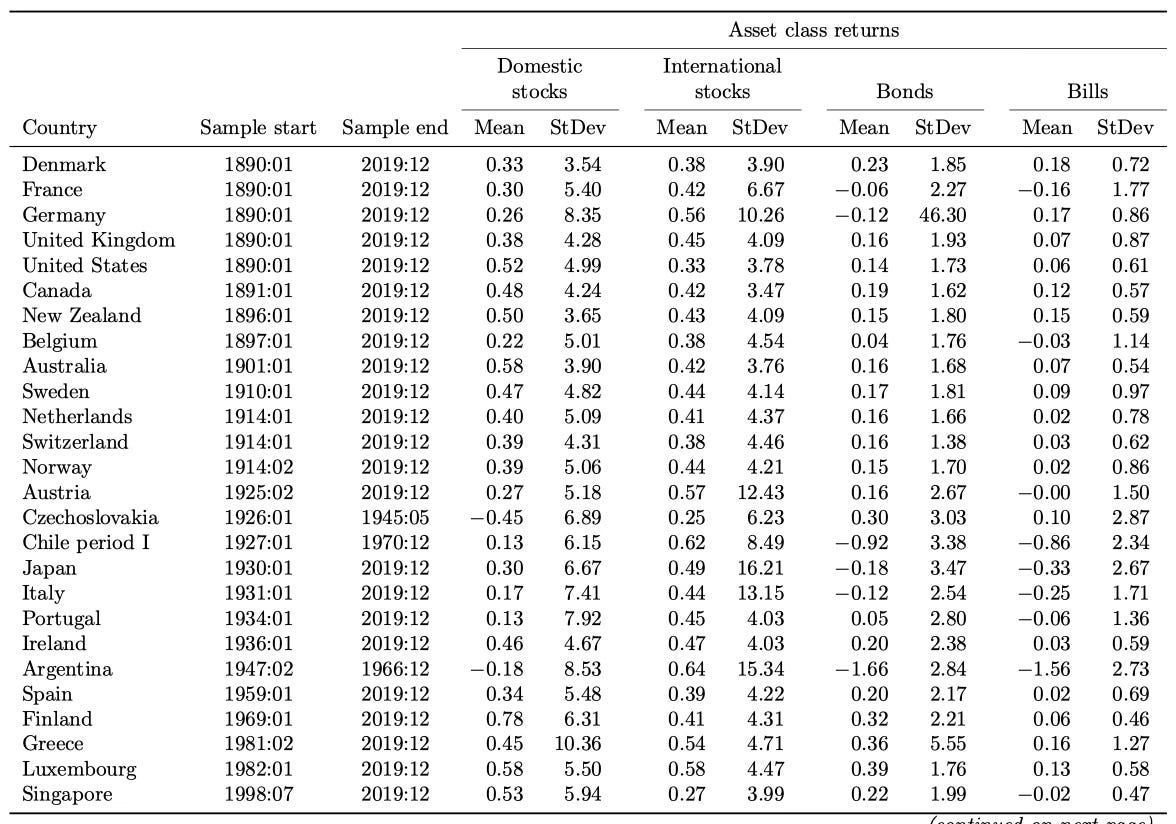

The graphics below capture the monthly real returns (geometric mean return and standard deviation of return) for domestic stocks, international stocks, bonds, and bills for some countries.

The FT article elaborates on the study findings, especially the counter-intuitive risk-return calculus.

The study assumes that the hypothetical couple saves 10 per cent of gross income, and then starts off draining 4 per cent of those funds a year at retirement. If the money runs out, they rely on social security, which is based on the US model, as is longevity. On average, parking entirely in stocks produces some 30 per cent more wealth at retirement than stocks and bonds combined. To get the same cash pile at retirement, someone blending into bonds would need to save 40 per cent more than an all-stocks saver. That is striking, but not so surprising — stocks have beaten bonds, and bills, everywhere since 1900, as UBS’s recent long-term markets study noted. But the really odd bit concerns the chance of so-called ruin, or running out of funds in retirement. A portfolio that bulks up in bonds as we get older comes with a 17 per cent chance of ruin. For domestic equities, the risk is about the same. But a half-and-half strategy of domestic and international stocks produces an 8 per cent chance of ruin.

The UBS long-term returns report mentioned above has some very interesting snippets. The UBS database, constructed by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh, and Mike Staunton (DMS for short), covers stocks, bonds, bills, inflation, and currencies for 35 economies (124-year histories for 23 of them, and over 50 years for the remaining 12). It’s complemented by 12 to 48-year histories for another 55 countries. The Indian database is since 1953, or 71 years. The report has several graphics capturing the evolution of equity market shares across countries, returns on various asset categories etc.

The report shows that in the long-run since 1900, equities have outperformed bonds and bills in every country. However, since the 1980s, bonds have been providing equity-like returns. It highlights that the majority of long-run asset returns are earned during easing cycles, a stage where central banks stand today.

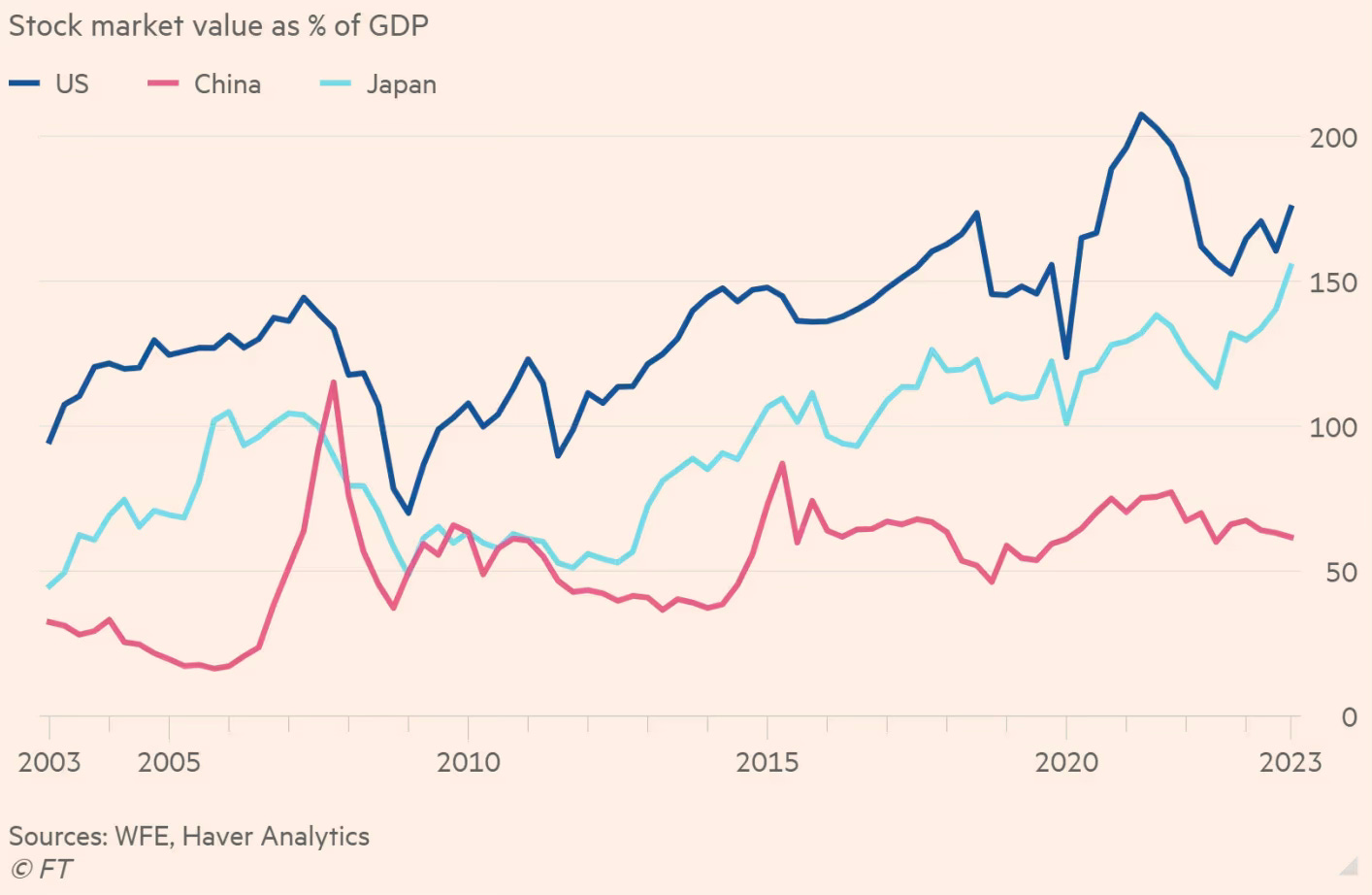

The report documents the geographical shares of equity markets. Compared to continental Europe (Amsterdam in 1608 and London in 1698), trading in marketable securities began in New York only in 1792. However, the US emerged as the biggest equity market at the turn of 1900 and took off in the 1920s. It’s interesting that in the second half of the eighties, the market capitalisation of Japanese equities surpassed the US, only for a very quick return to the norm by the end of the nineties. At its peak, start-1989, Japan accounted for 40% of global index, compared to 29% for the US. Today though the shares are 6% and 60.5% respectively.

The report notes an interesting paradox - the relative underperformance of high GDP growth markets compared to the lower-growth US market. The most striking illustration of this is China compared to the US.

As an endnote from the excellent UBS report, this is a striking snippet that captures how many of the salient aspects of today’s lives are such a recent phenomenon in the long-view of things.

At the start of 1900 – the start date of our global returns database – virtually no one had driven a car, made a phone call, used an electric light, heard recorded music, or seen a movie; no one had flown in an aircraft, listened to the radio, watched TV, used a computer, sent an e-mail, or used a smartphone. There were no x-rays, body scans, DNA tests or transplants, and no one had taken an antibiotic; many died young as a result. Mankind has enjoyed a wave of transformative innovation dating from the Industrial Revolution, continuing through the Golden Age of Invention in the late 19th century, through to today’s information revolution. This has given rise to entire new industries: electricity and power generation, automobiles, telecommunications, aerospace, airlines, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, oil, gas and alternative energy, computers, information technology, and media and entertainment…

Markets at the beginning of the 20th century were dominated by railroads, which accounted for 63% of US stock market value and almost 50% in the UK. 124 years later, railroads have declined almost to the point of stock-market extinction, representing less than 1% of the US market and close to zero in the UK. Of the US firms listed in 1900, some 80% of their value was in industries that are small or extinct today; the UK figure is 65%. Besides railroads, other industries that have declined precipitously are textiles, iron, coal and steel. These industries still exist but have largely moved to lower-cost locations in the emerging world. Yet similarities between 1900 and 2024 are also apparent. The banking and insurance industries continue to be important. Similarly, such industries as food, beverages (including alcohol), tobacco, and utilities were present in 1900 and continue to be represented today… within industrials, the 1900 list of companies includes the world’s then-largest candle maker and largest manufacturer of matches.

The report strikes a cautionary note on writing off traditional industries and their substitution with new and emerging technologies.

For example, we noted above that, in stock-market terms, railroads have been the ultimate declining industry in the US in the period since 1900. Yet, over the last 124 years, railroad stocks have beaten the US market, and outperformed both trucking stocks and airlines since these industries emerged in the 1920s and 1930s. Indeed, the research in the 2015 Yearbook indicated that, if anything, investors may have placed too high an initial value on new technologies, overvaluing the new and undervaluing the old.

The report is very good and has several interesting graphics. Unfortunately restrictions on reproduction without “explicit written permission” prevent me from posting more of the graphics.

No comments:

Post a Comment