The global financial markets are dominated by two institutions as never before - JP Morgan Chase in banking and BlackRock in asset management. The two institutions are bigger than too big to fail, and their Chief Executives Jamie Dimon and Larry Fink command extraordinary influence in policy making. They are the two individuals policymakers in the US turn to at times of financial market distress. In fact, it would not be a hyperbole to say that in some areas they are the market itself.

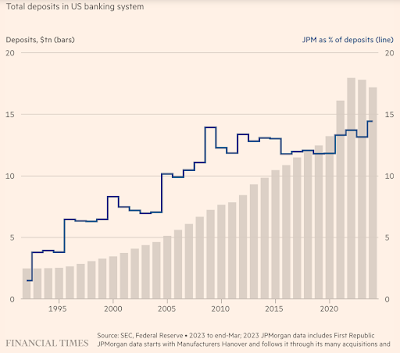

The recent decision by the US Government to sell the failing First Republic Bank to JP Morgan makes the latter even more systemically important. With this, in the space of 15 years, JP Morgan has been responsible for taking over Washington Mutual in 2008 and First Republic Bank, the largest two bank failures in US history.

This is a brief description of the First Republic deal

The First Republic deal was different from the structures agreed for Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, the two lenders that collapsed in early March, but similar in that it was another ad hoc solution to the sector’s problems. All deposits were taken over by JPMorgan, which meant the US government did not have to declare the bank a “systemic risk” to protect deposits over the $250,000 guarantee limit. At the same time, JPMorgan secured a loss-sharing agreement with federal regulators to avoid any hit from the most problematic loans on First Republic’s books, a crucial sweetener for the buyer.

The bank now holds slightly less than 15% of all US banking sector deposits. This further increases the too big to fail (TBTF) moral hazard. Its rise in recent years has been meteoric

JPMorgan today, with $3.7tn in assets and 250,000 employees, is the result of a centuries-long consolidation process. Its heritage includes a company started by the US founding father Alexander Hamilton, the investment bank run by legendary financier John Pierpont Morgan as well as lenders that financed the Erie Canal, the Brooklyn Bridge and the UK and French armed forces in the first world war. Even as recently as 1991, the retail bank that would eventually become a global banking juggernaut had only $37bn in deposits. The group now has almost $2.5tn and its market share has grown by 10 times, from 1.5 per cent to 14.4 per cent.

... it was under Dimon, who joined the bank in 2004 when it took over Chicago-based Bank One, that the group really pulled ahead. JPMorgan is now the largest bank in the US by assets, deposits and market capitalisation, with Chase bank branches in 48 states. It also earns more from investment banking fees than any other Wall Street bank, consistently outranking Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America.

Max Abelson and Hannah Levitt (HT: Adam Tooze) wrote this in Bloomberg about JP Morgan and Jamie Dimon,

If you’re tempted to compare it to BlackRock Inc., remember that the money manager’s $9 trillion of assets are in funds it oversees for clients. JPMorgan, by comparison, finances the world (and has an asset management operation that’s itself about a third the size of BlackRock). And it processes more than $5 trillion of payments a day. You can think of it as an empire all its own. Bloomberg Opinion columnist John Authers goes further, calling Jamie Dimon the sun around which the financial system revolves and describing JPMorgan as a kind of public utility, big enough for the government itself to depend on...

Dimon likes to say that the bank has a fortress balance sheet, an image that political economist Mark Blyth elaborates on. “If the only game in town is a medieval fortress, I want to be inside,” says Blyth, who runs the William R. Rhodes Center for International Economics and Finance at Brown University. “Hey, we have the castle. Don’t you want to be in the castle? It’s dangerous out there.” In the first three months of the year, as other banks saw savers depart, deposits at JPMorgan rose. But there’s a problem with everyone wanting to be in the castle. “What happens if the castle walls get breached?” Blyth asks. “We’re all screwed.” Economic power in the US runs in eras. As Blyth puts it, after World War II, when society more or less had to be rebuilt, the fiscal capacity of the US Treasury dominated. When inflation became the enemy and the Fed had the power to fight it, fiscal dominance gave way to monetary dominance. Now too-big-to-fail banks’ becoming bigger could usher in something new. “We may be in a world of financial dominance,” he says. “I don’t know, but it sure smells that way.”

JP Morgan took over First Republic in an auction that had three other smaller banks, PNC, Citizens Bank, and Fifth Third, whose combined assets were less than a third of JP Morgan's. The bid parameter was the least loss to the FDIC, and JP Morgan's was the cheapest at $13 bn of estimated loss. But as the FT article writes, the sheer size of JP Morgan put it at a clear advantage compared to the three competitors. Besides given its sheer size, the Treasury and regulators would have naturally thought that a takeover by JP Morgan would have had a greater confidence-building effect on the banking system. Patrick Jenkins highlights the problem with such thinking

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which manages US bank failures and administered the First Republic transaction, made clear JPMorgan had won the deal ahead of other bidders, essentially thanks to its heft. It could afford to offer a better value package to the FDIC — and the organisation has a legal duty to choose the “least-cost” solution. But this is a self-perpetuating argument, and with the banking turbulence of recent months turning into a full-blown regional banks crisis, JPMorgan could well become the natural buyer of other troubled banks. That feels neither healthy nor sustainable. Respecting the “least-cost” law, without considering the longer-term bigger picture, is myopic.

This is perhaps an example of an instance where the government and regulators in the US ought to have kept life-cycle cost (instead of current cost-benefits) as a factor in their decision. It's one thing to ask JP Morgan to take over when nobody was willing (and JP Morgan had declined to take over Silicon Valley Bank at the height of the current banking crisis), but an altogether different thing to hand over the failing bank to JP Morgan when there were others willing to do so. Even at a higher cost, the regulators could have avoided JP Morgan and sent out a message. But that's unlikely given the political capture of decision-making in the US by Wall Street and Big Tech interests.

It also highlights how deeply entrenched the moral hazard of bailouts has become in the US. As Ruchir Sharma and others have pointed out, it's become all too evident that the policymakers are too scared of letting anything fail that they'll anyways come up with a bailout at the end. And the market participants have internalised this belief.

All failures have costs. But such bailouts have even greater costs. The real issue is this - do you want to suffer the immediate pain of a bank failure, or invite much bigger long-term harm through distortion of incentives and encouragement for recklessness which erodes the disciplining powers of financial markets and irreparably weakens the foundations of capitalism?

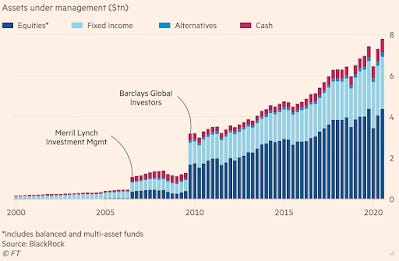

The rise of BlackRock in the asset management industry has been even more meteoric. Founded in 1988 as Blackstone Financial Management, it really took off after the global financial crisis. This is a good primer.

Its assets under management have risen spectacularly since the financial crisis, more than quintupling to briefly touch $10 trillion in early 2022.

This while a bit dated (from November 2020) is still relevant

The hit to the big banks from the 2008 financial crisis allowed it also to swoop on Barclays Global Investors, then the world’s largest fund manager, in time for the longest bull market in equities since the second world war. That acquisition included iShares, the exchange traded fund unit that has grown seven-fold on the back of a massive shift to passive investing and now accounts for a third of BlackRock’s assets. The iShares unit now accounts for 40 per cent of global ETF assets...

BlackRock amounts to a perpetual reinvention machine that has continually added new sources of growth, most recently from technology services to investors, including chunky contracts for its Aladdin risk management platform. Its $1.3bn acquisition last year of eFront, a risk analysis company, was the biggest deal for BlackRock since the Barclays purchase. The combination of economies of scale from client inflows and these new tech revenues allowed BlackRock to set a new record for operating margin in the third quarter, which at 47 per cent would draw the envy of the tech companies that have led the market this year

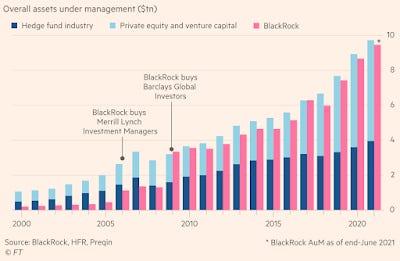

The most stunning graphic is this below - BlackRock on its own is about the size of all of the hedge fund and private equity and venture capital industries combined.

Its AUM has recovered to $9.1 trillion after a decline of $1.4 trillion in 2022, and the Fund is actively engaging on the alternatives side, an area dominated by the likes of Blackstone and KKR. It recently tried and failed to buy Credit Suisse.

Like with JP Morgan, BlackRock's large size gives it enormous advantages. It's amplified by its presence across the spectrum - asset management, ETF wealth management platform, risk management platform, advisory services, etc. As an illustration, its advisory arm was selected by the FDIC to help sell $114 bn portfolio of securities (mortgage-backed securities, collateralised mortgage obligations, and commercial mortgage-backed securities) inherited after the government takeover of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

BlackRock’s Financial Markets Advisory arm has long been the go-to team for central banks and governments when they need to deal with messy assets acquired during financial rescues. The financial powerhouse helped the US sell off assets from the 2008 collapses of Bear Stearns and AIG, evaluated troubled banks for the Irish and Greek governments, and advised both the Fed and the European Central Bank on asset purchase programmes.

Business transactions involving the Advisory arm and Aladdin feed into BlackRock's asset management business in many direct and indirect ways, and confer it an unfair advantage. In the circumstances, it's again not clear as to why BlackRock should have been selected for such sales, when the same could have just as well been done by others, perhaps at a slightly higher cost.

BlackRock is also one among the Big Three that dominate the global asset management industry, the others being Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors. A paper by Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst found

We document that the Big Three have almost quadrupled their collective ownership stake in S&P 500 companies over the past two decades; that they have captured the overwhelming majority of the inflows into the asset management industry over the past decade; that each of them now manages 5% or more of the shares in a vast number of public companies; and that they collectively cast an average of about 25% of the votes at S&P 500 companies... We estimate that the Big Three could well cast as much as 40% of the votes in S&P 500 companies within two decades. Policymakers and others must recognize — and must take seriously — the prospect of a Giant Three scenario.

As an update

As of the end of 2021, the Big Three collectively held a median stake of 21.9% in S&P 500 companies, which represented a proportion of 24.9% of the votes cast at the annual meetings of those companies.

In their latest paper, Bebchuk and Hirst refute with great detail the arguments against systemic risk creation and market concentration by the Big Three officials, and caution at the rising power of the Big Three. They argue that the diffused ownership in public companies and the prevailing market structure present the Big Three with the ideal conditions to influence major corporate decisions.

Even among the Big Three, BlackRock tops in its market influence,

Given that many shareholders don’t actually bother to vote at annual meetings, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street now account for about a quarter of all votes cast on average, which will rise to 41 per cent over the next two decades, the academics estimated... In reality, calling it the Big Three is a misnomer. State Street’s inclusion is the legacy of its invention of the ETF, and its size and growth rate is far more modest than BlackRock or Vanguard’s. In practice, there is an emerging duopoly, and BlackRock’s pole position — and Fink’s willingness to throw its heft around more than Vanguard — has made it a target across the political spectrum... A host of former government officials work at BlackRock, and others have departed for plum jobs in the Biden administration. To some critics, BlackRock is the new Goldman Sachs.

The Big Three's power is amplified by the rise of ETFs. BlackRock is the world's largest ETF fund manager. ETFs, like other index funds, have a unique issue - the underlying stocks of an index fund are not owned by the retail (and other) investors who buy the index fund, but by the fund manager, who there also owns the vote. This makes the fund managers of passive funds massively influential in so far as becoming a large voting shareholders in many companies. A US Senate working paper has documented several instances of strategic voting by the Big Three in the name of "investment stewardship". The paper makes several recommendations, mostly to enhance transparency and disclosure by the Big Three.

I can think of at least three problems with size on its own, each of which in itself is sufficiently strong enough to discourage corporate bigness, especially but not only in financial and technology markets. One, apart from the economies of scale, the magnitude of their size confers on these institutions several implicit advantages, including the cheaper cost of capital, preferential access to talent and market resources, leverage over the market ecosystem, additional margins for risk assumption, preferential treatment by regulators, and a carte-blanche backstop arising from too big to fail.

Two, given the complex and deeply interconnected nature of financial markets, institutions of the size of JP Morgan and BlackRock are too big to manage. These are bigger than all but a couple of countries. Three, a size of such magnitude is invariably accompanied by a seat at the top of the decision-making table. Given the stakes involved and the inexorable dynamic of market incentives, such access invariably translates into being able to decide the rules of the game. Such political capture corrodes capitalism and democracy.

The behemoths among Wall Street and Big Tech companies are the most egregious exhibits. It's time that regulatory scope expands beyond present and future consumer welfare and looks at these far more dangerous factors.

No comments:

Post a Comment