Substack

Monday, November 28, 2022

A proposal for unlocking bank finance in infrastructure projects

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Weekend reading links

Today’s two dominant organisational forms are practically the same: the one-man autocratic state and the one-man autocratic company. Both have the same vulnerability: the idiosyncrasy of an overpraised loner... One-man states and one-man companies have similar cycles. At first, even if the autocrat’s aim is self-enrichment, he wants approval, so he avoids self-sabotage. Being unbound by rules, he seems more agile than his collectively ruled rivals. With success, he acquires an aura. He stabilised Russia/invented Facebook/built electric cars. Why, he’s a genius! If he wants to become president for life or assign himself stock with 10 times the voting rights of other shares, well, what could possibly go wrong? Having defied gloomsters the first time around, the autocrat ignores them the second time But the initial success was generally due to a unique confluence of luck, person and moment. Few humans are two-trick ponies. Worse, hubris takes hold. Having defied gloomsters the first time around, the autocrat ignores them the second time...The investor Chris Sacca tweeted last week: “One of the biggest risks of wealth/power is no longer having anyone around you who can push back . . . A shrinking worldview combined with intellectual isolation leads to out-of-touch shit . . . I’ve recently watched those around him become increasingly sycophantic and opportunistic . . . agreeing with him is easier, and there is more financial & social upside.” Sacca was talking about Musk but he might as well have meant Putin.

3. The UK government has announced windfall taxes on oil companies who have raked in multi-billion dollar profits from the high oil and gas prices even as governments struggle to subsidise consumers,

The logic seems straightforward. Energy suppliers are benefiting from an unexpected bonanza because of Europe’s sudden move away from Russia’s gas and oil after its invasion of Ukraine, as opposed to any savvy strategy by the companies themselves. Shell, based in London, recently reported that it had earned $20 billion in just six months, its biggest haul on record, while BP earned $16.6 billion. TotalEnergies, based in Paris, reported profits of nearly $29 billion over the same period. American energy companies are also taking in gobs of profit. Net income for the world’s oil and gas suppliers will reach $4 trillion, the International Energy Agency estimated, double last year’s total...

On Thursday, Jeremy Hunt, Britain’s chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that he would raise $16.5 billion next year by increasing the windfall tax on oil and gas companies to 35 percent from 25 percent and introducing a temporary 45 percent levy on electricity producers. Many of these producers — including those that use solar, wind and nuclear power — have enjoyed enormous profits even though their costs haven’t increased. The European Union last month announced a temporary tax — euphemistically labeled a “solidarity contribution” — on some fossil fuel producers. An additional 33 percent levy will apply to “surplus” profits and is expected to raise $145 billion. There is also a cap on electricity profits. Individual nations have gone further. Last week the Czech Parliament approved a measure to impose a 60 percent tax on energy companies’ and banks’ windfall profits. Germany is considering taxing by 90 percent profits that electricity companies generated above the cost of production...

Yet as several economists have pointed out, whatever the drawbacks, a windfall profit tax makes the most sense when energy companies are making gargantuan profits and families and businesses are facing financial ruin from staggering energy costs. Concerns about crimping investment may also be overstated, they noted, when so many of the oil and gas companies are using the newfound revenue to increase payouts to shareholders and buy more of their own stock to nudge up its price... In a survey of more than 30 European economists conducted in June by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, half agreed that a windfall tax on excessive oil and gas profits should be used to help households afford high energy costs. Seventeen percent were opposed, while a third were undecided.

Spain followed suit with its lawmakers approving imposition of windfall taxes on banks and energy companies.

Spain wants to raise a total of €3bn from big banks over the next two years via a 4.8 per cent tax on their income from interest and commissions. From utilities, it is aiming to raise €4bn over the same period with a 1.2 per cent tax on their sales.

4. The hypocrisy surrounding calls to boycott the Qatar World Cup because its stadium construction involved exploited migrant labour is staggering. For countries which have a history of colonial exploitation of the worst kind, and that too not many decades back, and which have supported much worse Chinese genocide in Xinjiang, this concern is very rich. Gianni Infantino was right to call this out.

Worst of all, the arguments about LGBT rights etc can rightfully be construed by Qataris as an attempt to impose emerging western cultural norms on the Conservative Qatari society.

5. FT has a long read which highlights Apple's dependency on China,

Apple’s reliance on the country as its manufacturing base — with responsibility for 95 per cent of iPhone production, according to Counterpoint, a market intelligence group — leaves the business vulnerable to supply chain shocks... Operating profits in greater China — which includes Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and mainland China — have shot up 104 per cent over 24 months to $31.2bn in the financial year to September, eclipsing the $15.2bn earned by Tencent and the $13.5bn from Alibaba in their most recent 12-month period, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence... As Huawei’s share of the Chinese market plummeted from a high of 29 per cent in mid-2020 to just 7 per cent two years later, Apple’s share jumped from 9 per cent to 17 per cent, according to Counterpoint. Virtually all of the US group’s sales were in the premium segment, where its dominance climbed from 51 per cent to 72 per cent in three years.

6. Fascinating twitter thread on how Peru has in less than 10 years risen to become the world's second largest blueberry grower and largest exporter (HT:Adam Tooze).

Carlos Gereda was the spark that lit Peru's blueberry boom of the past decade. He asked a simple question: "can blueberries grow in Peru?" In 2006, he brought 14 varieties from Chile to see which ones adapted well to the Peruvian climate. He narrowed it down to four and, in 2009, founded Inka's Berries. The company's service consisted of assisting the development of plantations that adhered to the growing standards Carlos had conceived. The blueberry revolution ensued. In a very short time, Peru became the world's number two producer of blueberries and the world's number one in exports and per capita production. Seriously, the growth resembles that of bitcoin's value. In 2010, Peru produced 30 tons of blueberries; in 2020, 180K. This new industry ($1B in 2020) that was born seemingly out of nowhere is being led by corporations that can afford the high cost of entry. Most notably, Camposol and Hortifrut hold a combined 34% of the market. Peru's climate allows for year-round production, giving the country a competitive edge over seasonal agriculture. The productivity of Peruvian land is 13 tons per hectare. The world's top player, the USA, produces 8 tons per hectare.

7. Housing tenure ownership patterns across advanced economies

Visa last month reported annual net income of $15bn, up 21 per cent year on year. Both it and Mastercard are trading close to record highs. They have a combined market cap of $765bn, unchanged over the past year, even as the broader market has declined sharply. Ironically, it is the challengers, big and small, that are suffering more. The core explanation is simple: even the smartest fintechs are not fundamentally disrupting the market; they are merely slotting themselves into the existing payments architecture. Yes, they may make life easier for the consumer or the merchant with faster back-end processing or slicker point of sale interfaces. But this is not at the expense of Visa and Mastercard, whose electronic “rails” they nearly all rely on. The big old card companies might look ripe for disruption, facilitating as they do high “interchange” fees levied via merchants (averaging 2 per cent in the US). But thanks to the spread of their operations into every corner of the world, it has been either impossible or economically unappealing for potential competitors to build new kinds of networks.

9. Agricultural crop yields in India remains much lower than elsewhere

Soy yields in India are three-four times lower compared to the US and Argentina, while mustard yields are almost half compared to canola grown in Canada (mustard and canola belong to the same Brassica genus). India imports both varieties of edible oils to meet its large domestic shortfall. India is among the top producers of cotton in the world but yields are less than a fourth when compared to China. Average rice yields in India are 57% of China and lower than even Bangladesh and Vietnam. India is the largest producer of milk in the world but cattle milk yields (per animal per year) are 60% of China and less than a fifth of the US.

Amazon’s earnings report showed that its revenue from advertising was higher than fees from its Amazon Prime membership scheme, audiobooks and digital music combined, as well as more than twice the sales from its physical stores, including the Whole Foods grocery chain.

11. Bradford De Long makes an important point about the inflation target,

I think that [former Federal Reserve chair] Paul Volcker, who’d stopped [tightening monetary policy] when inflation was down to 4 per cent, was right. And Alan Greenspan [his successor], who said we should be happy that it has fallen to 2 per cent and stick there, was wrong. You really do, given the difficulties and getting your fiscal policy ducks in a row, want to have the ability to deliver a major stimulus to the economy when it falls into recession, to be able to cut interest rates by five percentage points or so. It really does require that the average inflation rate be something significantly higher than two, for interest rates to be in a configuration so that you can respond, rather than finding yourself once again at the zero lower-bound and you’re unable to convince people to spend to get the economy back to full employment. That reversing the shift from Volcker’s 4 per cent to Greenspan’s 2 per cent is something that really needs to be done.

He admits that the Russian invasion may have had the effect of raising inflationary pressures, but also feels that some inflation post-pandemic may be useful,

Right now, we have succeeded in reopening the economy after a plague, in a different, much more delivery-and-goods-production orientation, relative to in-person sales. More people driving delivery trucks, making goods and programming websites than before. And as always, when you wheel the economy into a new configuration — 1947 and 1951 are my stock examples — you need a little bit of a burst of inflation to grease things. If things go well, you just get a short transitory burst, after which things return to normal because everyone understands that this isn’t that monetary policy has lost its anchor. It’s more that the market economy is doing its thing by putting high prices on things that are [stuck in] bottlenecks. And offering higher wages to workers who will move into expanding industries.

12. Finally, Hal Brands has a series of articles on the importance of a US-led Indo-Pacific alliance involving Japan, India, Australia, and UK in deterring any Chinese invasion of Taiwan. He quotes US officials in pointing to the possibility of a war in 3-5 years. He writes,

A war that the US fights in the Western Pacific without allies is a war it runs a very high risk of losing. A war that it fights at the head of a large democratic coalition is one China probably cannot win. The more Beijing fears the latter scenario, the better deterred it may be from using force in the first place. The Chinese-American rivalry is a contest for Indo-Pacific hegemony. But in what they do and don’t do, an array of middle powers will have their say in who wins.

So how might India react if China attacked Taiwan? Although India can’t project much military power east of the Malacca Strait, it could still, in theory, do a lot. US officials quietly hope that India might grant access to its Andaman and Nicobar Islands, in the eastern Bay of Bengal, to facilitate a blockade of China’s oil supplies. The Indian Navy could help keep Chinese ships out of the Indian Ocean; perhaps the Indian Army could distract China by turning up the heat in the Himalayas. Even short of military assistance, India could rally diplomatic condemnation of a Taiwan assault in the developing world...New Delhi has a real stake in the survival of a free Taiwan. China has a punishing strategic geography, in that it faces security challenges on land and at sea. If taking Taiwan gave China preeminence in maritime Asia, though, Beijing could then pivot to settle affairs with India on land... a world in which China is emboldened — and the US and its democratic allies are badly bloodied — by a Taiwan conflict would be very nasty for India... What India would do in a Taiwan conflict is really anyone’s guess. The most nuanced assessment I heard came from a longtime Indian diplomat. A decade ago, he said, India would definitely have sat on the sidelines. Today, support for Taiwan and the democratic coalition is conceivable, but not likely. After another five years of tension with China and cooperation with the Quad, though, who knows?

The Economist has an article which describes India's foreign policy as "reliably unreliable"

Ever since India won independence in 1947 its foreign policy has prioritised developing its economy, defending its territory and maintaining influence and stability in its neighbourhood. And it has done so imbued with a profound fear of being dominated by a more powerful country as it was for so long.

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

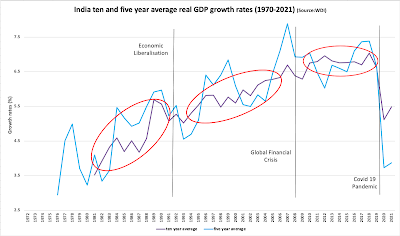

Thoughts on the emerging trends on the quality of India's economic growth

This is the second part of posts on my evolving thoughts on the Indian economic prospects. In the first part early this week on India's economic prospects, I had blogged about the expectations about the future trajectory of economic growth. In the spirit of being cautious and perhaps undertaking a pre-mortem, this post will focus on some emerging trends in the quality of economic growth.

While I believe that India appears best positioned among all major economies to ride out the impending recession in the developed economies, question marks hang over the quality of its longer-term growth trajectory. Fundamentally, even with a 6% growth, what is the likelihood that it would be broad-based than skewed? Will the rising tide lift all the boats?

Let me illustrate the point with one data point. The trends on two and four-wheeler sales in India over the 2010-22 period reveal some interesting insights, especially in the sharp divergence post-pandemic.

Monday, November 21, 2022

Indian economy - thoughts on the growth trajectory

This is the latest post on my evolving thoughts on the Indian economy. I'll have two posts on this. The first will focus on the expectations about the trajectory of economic growth going forward and the second on some emerging trends in the quality of economic growth.

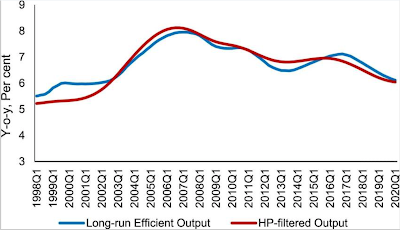

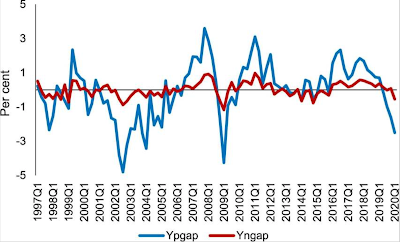

The results suggest that a combined deceleration in neutral and investment-specific technology growth post 2016, brought down the potential growth to around 6 per cent in 2020Q1. The output gap also witnessed a persistent decline since 2018Q1, primarily due to weak demand and a rise in investment adjustment costs reflecting heightened stress in the investment and financial sectors... We find that the long-run efficient output is a better estimate of potential output... According to this estimate, potential growth in India witnessed a sustained increase from 2002 to 2007, and remained subdued thereafter... We also find that the sudden uptick (2002 onwards) in potential growth is mainly driven by neutral growth.

Thursday, November 17, 2022

The challenge of sustaining DB pension funds

The shock in the UK market for liability driven instruments (LDI) has drawn attention to the issue of hedging for gaps in the existing defined benefit (DB) pension schemes, and the larger issue of returns for pension funds. Along side the declining returns on investments, at least for sometime, pension funds (DB ones) face the problem of rising inflation and therefore higher inflation adjusted pension liabilities.

John Mauldin points to how the traditional 60:40 stocks to debt portfolio, the workhorse portfolio of investment, is being whacked this year, as bonds are having one of their worst years ever.

Government bonds are having the fourth worst year in 2022 after 1721, 1865, and 1920.Years of falling interest rates raised pension liabilities—a big problem for plan sponsors and managers. Lower interest rates reduced the return on the bond portion of a pension fund. In a world of zero and negative interest rates, pension funds simply couldn’t make their target returns (typically 7% and sometimes more) when 40%+ of the portfolio was making 2‒3% (at best!). Consultants then pushed them toward something called “Liability-Driven Investment” or LDI, basically a leveraged hedge fund strategy betting interest rates would keep dropping. They showed data that for the last 30 years the trade ALWAYS won. Except the last 30 years was a period of falling rates and inflation, which everyone assumed would continue. It worked well until rates went higher.

In the US, the problem is not with LDIs but the high exposure to equities and alternative assets, which could have an extended period of downturn.

Asset allocation by the UK’s 5200 odd DB schemes has shifted dramatically over the past 15 years. These funds collectively have more than 10mn members and £1.5tn assets under management. At the end of 2021, they were 72 per cent allocated to bonds, 19 per cent to equities and the rest to other investments such as property and hedge funds, according to the Pension Protection Fund, the lifeboat scheme for the sector. This contrasts with 2006, when they were 62 per cent invested in equities and 28 per cent in bonds. This trend reflects how regulation and politics have pushed DB pension funds out of equities to invest more heavily in bonds, which are considered “safe” assets that reduce the risk to the portfolio and sponsoring employer.

On the issue of pension systems, Mauldin points to a Mercer report that evaluates different pension systems.

Economic sandpiles that have many small avalanches never have large fingers of instability and massive avalanches. The more small, economically unpleasant events you allow, the fewer large and, eventually, massive fingers of instability will build up.Efforts by regulators and central bankers to prevent small losses actually create the large fingers of instability that bring down whole systems and spark global recessions. And, increasingly, the unfunded liability of government promises will be the most massively unstable finger.In that crisis, things that should be totally unrelated will suddenly become intertwined. The correlations of formerly unrelated asset classes will all go to one at the absolute worst time. Panic and losses will follow. Governments will try to stem the tide, perhaps appropriately so, but, eventually, the markets have to clear.There is a surprising but critically powerful thought in that computer model from 35 years ago: We cannot accurately predict when the avalanche will happen. You can miss out on all sorts of opportunities because you see lots of fingers of instability and ignore the base of stability. And then you can lose it all at once because you ignored the fingers of instability.

The point about the risks with DB plans is of relevance to India too. The high returns earned by the New Pension Scheme (NPS) trust till date should not blind us to the strong likelihood (I would go so far as to say near inevitability) of far lower returns in the decades ahead. As the OECD Pensions Survey indicate, India's annual average returns are much higher than in any other country.

This is perhaps validated by the much higher 10 year government bond yields in India compared to the standards of emerging economies, a trend which cannot be sustained as the country undergoes more global financial market integration.

I had blogged earlier drawing attention to the role of demographics and other factors in contributing to a secular decline in global interest rates. There is nothing to suggest that the same should not apply to India. Taking all together, the days of near double-digit pension growth rates clearly appear on the rear-view mirror.

All this makes the trend on reversion to defined benefit pension schemes in some Indian states even more disturbing.

Monday, November 7, 2022

PE asset stripping - Albertsons and Kroger edition

The announcement that grocery chain Kroger would be buying Albertsons for $24 bn has raised a controversy. For one, the combined entity would be the second largest supermarket chain in US after Walmart, with 15% of national grocery business, employ over 700,000 people, have over $200 bn in revenue, and more than 40,000 private label brands.

This is the major source of controversy,

The merger announcement said that, as part of the transaction, Albertsons Companies will pay a special cash dividend of up to $4 billion to its shareholders of record on October 24, 2022... This dividend equals about a third of the supermarket chain’s market value. Almost 70 percent of this special dividend will go to its former private equity owners plus Apollo Global Management, which purchased a minority share in Albertsons last year. This will be a spectacular windfall for Cerberus, enriching the PE firm and its owners while putting the future of the Albertsons chain and its workers at risk... While the general view of financial markets is that the FTC and the courts will not let the merger go through, the payment of this special dividend sets Albertsons up for failure and provides Kroger with a powerful “failing firm” defense of its merger proposal. Kroger can argue that Albertsons will face bankruptcy if the merger is not approved.

Matt Stoller points to the problems with the $4 bn special dividend,

The problem is that in this case, that cash is pretty much all the liquidity that Albertsons has. According to the firm’s latest 10Q, Albertsons has $3.213 billion of cash and $565 million of receivables, which can be quickly sold to raise cash. There’s your special dividend right there.

He also writes that the merger is the latest in a trend over the last thirty years whereby supermarket chains have consolidated the nearly $1 trillion grocery industry, which provides the source for what Americans eat. The consolidation in the industry has been steep.

There has been tremendous concentration on both a national and local level already. As Errol Schweizer at Forbes noted in an excellent piece published immediately after the deal came out, “There are already 30% fewer grocery stores than a few decades ago and most major metropolitan areas (with the exception of New York City) are heavily concentrated among just a handful of grocery chains.” That means large chains not only secure better prices for goods than their smaller counterparts, but can also increase prices faster than costs, contributing to inflation. Suppliers, consumers, and workers will all feel the pressure from Kroger/Albertsons, and since suppliers buy from farmers, farmers will feel it too, at least indirectly...There will be layoffs in white collar jobs such as “office-based marketing, procurement, analytics, digital sales and category management roles,” which the firm calls ‘synergies.’ Kroger will have more bargaining power over suppliers, as it will have 5,000 stores and can “more easily set payment terms, negotiate shelf space and assortment, and extract better costs and greater trade allowances for promotions, couponing, ad placement and slotting fees.” In addition, deals like this concentrate grocery shelves with the goods of certain dominant firms in packaged foods categories, such as “Pepsico, Kraft Heinz, Nestle and Kelloggs, as well as meat and poultry barons such as Tyson, JBS and Smithfield, centralizing industrial agricultural supply chains.” This will further centralize the food supply overall and could potentially prevent the stocking of more seasonal and local food. Finally, Kroger and Albertsons are combining their data hoards and advertising network, which could be quite significant.

Sunday, November 6, 2022

Weekend reading links

1. Tamal Bandopadhyay draws attention to the workforce decline in the banking industry,

In 2005, clerks and subordinates combined had at least 63 per cent share of employees in scheduled commercial banks. By 2021, this figure has more than halved — 30 per cent. A large part of the shrinkage happened in the past decade. Till 2010, clerks and subordinates formed at least 55 per cent of total banking employees. Blame it on technology. As digitisation progresses, more and more jobs of the clerical cadre are turning redundant... As a result of the core banking solution (CBS), customers no longer bank with a branch; they bank with a bank (at any branch across the nation)... The number of branches has gone up by more than one-fourth in the past decade but the number of employees has fallen.

2. FT has a long read which highlights how Taiwan's strategic interests may be coming in the way of America's desire for TSMC to diversify quickly by building facilities in US.

TSMC has grown into a giant with an effective stranglehold on the global chip supply chain. Taiwan sees this dominance as a crucial security guarantee — sometimes referred to as its “silicon shield”. The government believes that the concentration of global semiconductor production in the country ensures the US would come to the rescue if China were to attack. “Everyone needs more advanced [ . . . ] semiconductors,” economy minister Wang Mei-hua said during a visit to Washington this month. Being a key global player in this way will “make Taiwan [ . . . ] safer and [secure] peace”, she added. But Taiwan’s determination to keep as much of the industry as it can on the island is clashing with US strategic goals and its fears of China... As competition between the US and China heats up and the risk of a military conflict over Taiwan increases, Washington is seeking to both cut Beijing off from supplies of key advanced semiconductors and reduce its own dependency on Taiwan for chip supplies. Both of those objectives potentially undermine TSMC, whose success is built on serving customers in all markets and on doing so from a cost-efficient cluster of plants almost entirely in Taiwan.

Its dominance of the market is complete

Taiwan now accounts for 20 per cent of global wafer fabrication capacity, the single largest concentration in one country, and a staggering 92 per cent of capacity for the most advanced chips. The US share in global chip manufacturing has dwindled from 37 per cent in 1990 to 10 per cent in 2020.

3. Another aspect of Japanification is the hollowing out villages and empty houses

Next year, according to a recent estimate, Japan will have roughly 11mn unoccupied residences — slightly more than the entire residential stock of Australia. By 2038, under one scenario in the same forecast, just under a third of Japan’s dwelling units could lie empty. A gloomy prognosis for Japan, where spooky, semi-abandoned rural villages already abound, but a portent of much bigger trouble, potentially, for China. For many economies, Japanification may be a vague worry; where bubbles are concerned there is danger. And there’s a warning klaxon that Japan may now be sounding for China relating to the effect of demographics.

4. Arvind Subramanian makes one of the strongest yet cases on restricting capital flows.

... cross-border flows of private financial capital do not foster sustained economic growth. The substantive benefits from financial globalisation, if any, are too few to offset the costs of sudden shocks, capital flight, and loss of policy control... Developing and emerging-market countries must impose constraints on the cross-border flow of certain forms of capital, particularly volatile portfolio flows. Only “good capital”— for example, foreign direct investment that has a long-term stake in the recipient country and brings technology, skills, and ideas to it — should enjoy the right to move across borders.

Instead of panic-driven capital controls when capital flows reverse, developing countries should eschew the temptation to further liberalise capital flows, especially for short-term gains.

5. After the struggles with overcoming its gas dependency on Russia, Germany grapples with the challenge of derisking its economic fortunes away from China. But Chancellor Olaf Scholz appears as yet not ready to take harsh decisions with the country's China relationship.

The FT writes about the controversy around and tensions created within Germany about the recent purchase of a minority stake in a Hamburg container terminal by a Chinese shipping company Cosco,

Rarely has a deal encountered such strong government opposition. Six German ministries came out last month against Chinese shipping company Cosco’s planned acquisition of a stake in a Hamburg container terminal. But it went through anyway. The man who ensured its safe passage through the German cabinet was Chancellor Olaf Scholz. He insisted on a compromise — Cosco would have to make do with a 25 per cent stake, rather than the 35 per cent that was initially proposed. But the German foreign ministry remained opposed, even after Scholz pushed it through. State secretary Susanne Baumann wrote an angry letter to Scholz’s chief of staff, Wolfgang Schmidt, saying the transaction “disproportionately increases China’s strategic influence over German and European transport infrastructure and Germany’s dependence on China”. Scholz, however, clearly could not afford to see the deal collapse. On Friday he will become the first G7 leader to hold talks in Beijing with Chinese president Xi Jinping since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Nixing the Cosco transaction would have cast a long shadow over a trip with huge symbolic importance to both Beijing and Berlin...

The coalition agreement negotiated last year by Scholz’s Social Democrats, the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats was notable for its critical tone on China and its focus on human rights. But the Hamburg deal shows deep divisions persist between the Greens and parts of the SPD about the future of the relationship. Green scepticism about China has only grown since last month’s Communist party congress, during which President Xi stacked the Politburo Standing Committee with loyalists and cemented his position as the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong... The Ukraine war exposed the folly of Germany’s decades-long reliance on Russian gas. Now, the pessimists fear, it may be about to pick up the tab for its even deeper dependence on China, a country that has long been one of the biggest markets for German machinery, chemicals and cars. Thomas Haldenwang, head of German domestic intelligence, summed up the concern at a hearing in the Bundestag last month. China, he said, presented a much greater threat to German security in the long term than Russia. “Russia is the storm,” he said. “China is climate change.”

Interestingly, even as the smaller companies are tapering down their China operations, it's the bigger ones that appear reluctant, with some like BMW and BASF even expanding operations despite the obvious risks. A clear example of the divergence between national interests and those of multinational corporations.

Scholz's reluctance to bite the bullet with China is surprising since China may be needing Germany more than the other way round given China's deepening rift with the US. The Times writes,

China now makes a very wide range of factory equipment that it used to buy from Germany. Covid lockdowns and a wave of nationalism have also hurt consumer spending on imports in China. At the same time, Germany has gone on buying ever more goods from there. The result is that Germany’s longtime trade surplus with China vanished late last year and has been replaced by a steadily widening deficit. Many German companies now see China as a competitor at home instead of an opportunity abroad. “People always talk about how China is a big market — no, China is a huge economy with a small accessible market,” said Jörg Wuttke, the president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. Overall, E.U. exports to China are only slightly larger than those to Switzerland... President Emmanuel Macron of France had urged Mr. Scholz not to travel to Beijing on his own but as part of a joint delegation. The head of Germany’s foreign intelligence agency warned that the country was “painfully dependent” on China.

6. Even as Germany prevaricates on China, there are signs that Europe may be succeeding faster than expected in weaning itself away from Russian gas. The price at Dutch-based virtual natural gas trading point, TTF, has declined.

Prices remain eye-wateringly high, particularly for early next year, and when the cold weather finally hits there remain concerns Europe could quickly burn through its gas reserves, potentially still leading to extreme tightness in supplies after Christmas. Gas at around €115 per megawatt hour is still equivalent to almost $180 a barrel in oil terms. Contracts in December and January are above $230 a barrel equivalent...But weather’s dominance over the gas market means Henning Gloystein at Eurasia Group is not quite prepared to say the worst is definitely over. If the winter is mild, then Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, could end the season with its storage facilities almost half full. But if it is just slightly colder than normal, then “German gas inventories would be virtually depleted by end-March, possibly requiring late winter rationing or supply cuts”, Gloystein said.

Whatever the final outcome in the months ahead, the European collective resolve to wean away from Russia is succeeding. Germany led this effort. It now needs to lead a similar effort to de-risk from China.

7. Martin Wolf writes about deglobalisation.

Interestingly, rich countries with greater trade integration are associated with lower inequality, pointing to possible gains from trade which benefits the entire economy.