1. Harish Damodaran has an excellent oped about the real number of farmers in India, questioning the conventional wisdom of 100-150 million farming households,

The 2016-17 Input Survey report shows that out of the total 157.21 million hectares (mh) of farmland with 146.19 million holdings, only 140 mh was cultivated. And even out of this net sown area, a mere 50.48 mh was cropped two times or more, which includes 40.76 mh of irrigated and 9.72 mh of un-irrigated land. Taking the average holding size of 1.08 hectares for 2016-17, the number of “serious full-time farmers” cultivating a minimum of two crops a year — typically one in the post-monsoon kharif and the other in the winter-spring rabi seasons — would be hardly 47 million. Or, say, 50 million.The above figure — less than half or even a third of what is usually quoted — is also consistent with other data from the Input Survey. These pertain to the number of cultivators planting certified/high yielding seeds (59.01 million), using own or hired tractors (72.29 million) and electric/diesel engine pumpsets (45.96 million), and availing institutional credit (57.08 million). Whichever metric one considers, the farmer population significantly engaged and dependent on agriculture as a primary source of income is well within 50-75 million.

This point about the farmer's worsened terms of trade is instructive,

In 1970-71, when the minimum support price (MSP) of wheat was Rs 76 per quintal, 10 grams of 24-carat gold cost about Rs 185 and the monthly starting pay for a government schoolteacher was roughly Rs 150. Today, the wheat MSP is at Rs 1,975/quintal, gold prices are Rs 45,000/10g and the minimum salary of government schoolteachers is Rs 40,000/month. Thus, if 2-2.5 quintals of wheat could purchase 10g gold and pay a government primary schoolteacher’s salary in 1970-71, the farmer has to now sell 20-23 quintals for the same. Fifty years ago, one kg of wheat could buy one litre of diesel at MSP. Today, that ratio is upwards of 4:1.

The real motivations and political economy in demanding MSPs,

The demand for making MSP a legal right is basically a demand for price parity that gives agricultural commodities sufficient purchasing power with respect to things bought by farmers. It is coming mainly from the 50-75 million “serious full-time farmers” who have surplus to sell and with real stakes in agriculture. They are the ones whom “agriculture policy” should target. Most government welfare schemes are aimed at poverty alleviation and uplifting those at the bottom of the pyramid. But there’s no policy for those in the “middle” and in danger of slipping to the bottom.An annual transfer of Rs 6,000 under PM-Kisan may not be small for the part-time farmer who earns more from non-agricultural activities. It is a pittance, though, for the full-time agriculturist who spends Rs 14,000-15,000 on cultivating just one acre of wheat and, likewise, Rs 24,000-25,000 on paddy, Rs 39,000-40,000 on onion and Rs 75,000-76,000 on sugarcane. When crop prices fail to keep pace with escalating costs — of not only inputs, but everything the farmer buys — the impact is on the 50-75 million surplus producers. They have seen better times, when yields were on the rise and the terms of trade weren’t as much against agriculture.

2. Mariana Mazzucato writes,

Consider the $40 billion the US government invests every year in the National Institutes of Health. The NIH (along with the US Department of Veterans Affairs) backed the Hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir with over 10 years of taxpayer-funded research. But when the private biotech company Gilead Sciences acquired the drug, it priced a 12-week course of pills at $84,000. Similarly, one of the first antiviral treatments for Covid-19, Remdesivir, received an estimated $70.5 million in public funding between 2002 and 2020. Now, Gilead charges $3,120 for a five-day course of it.This speaks to a parasitic, rather than a symbiotic, partnership. The NIH must do more to ensure fair pricing and access to the innovations it funds, rather than chipping away at its own power, as it did in 1995 when it scrapped the Fair Pricing Clause from its cooperative research and development agreements.

3. Fascinating FT long read that describes the distortions engendered by the entry of private equity into the market for veterinary care, traditionally offered as small, locally owned enterprises. It narrates the example of UK veterinary care company IVC Evidensia which was bought over by Swedish PE firm EQT in 2016, and has since been on an acquisition spree snapping up local independent and small chains of vet care practices across Europe. It now is Europe's largest vet care provider with 1500 sites.

The IVC deal stands to be lucrative for its owners. It had been preparing to float in London this year until a last-minute change of course. Instead, in a February deal, Nestlé and California-based private equity group Silver Lake agreed to lead a €3.5bn investment at a valuation of €12.3bn. At the same time, the original EQT fund that bought the company sold most of its stake and a newer EQT fund bought in. The valuation is four times higher than just two years ago, and more than 32 times IVC’s earnings in the year to March — far higher than the levels at which buyout groups typically buy businesses, with the 2020 average in Europe being 12.6 times earnings according to a Bain & Co report. It is a “stratospheric valuation compared with those typically seen in leveraged finance”, according to a report published in April by data provider 9Fin. Such a valuation stands to make a big contribution to the pool of so-called “carried interest” bonus payments available to EQT executives, under standard private equity pay structures. On buying a practice, IVC centralises procurement and finance, and appoints business support managers to oversee practices. IVC sets financial targets for practices that several vets described as challenging. It recommends drug prices centrally, but says local practice management ultimately decides what to charge. However, the effort to meet targets can lead to steep price increases. One vet in southern England says the price of Metacam, a widely dispensed anti-inflammatory painkiller, rose at their practice by 28 per cent to £82.79 for a 100ml bottle after IVC took over. The price of ProZinc, an insulin for diabetic cats, rose 39 per cent to £99.34, the vet says, and Fortekor, a heart medication, rose more than 78 per cent to £76.85.

This is a good summary of the standard PE operating model,

IVC’s race for growth is the latest large example of a model used widely by the private equity industry. Known as a “roll-up”, it involves buying large numbers of smaller or independent businesses using debt, and merging them into a large group that can cut costs with economies of scale. Rival buyout groups have snapped up dental surgeries and petrol stations in a similar way. The model rests, in part, on a piece of financial engineering known as “multiple arbitrage”, in which buyout groups calculate that the price they pay for a small business, per dollar of its earnings, is lower than the price they can later receive for it as part of a bigger group. In the process, the companies typically amass large debts. IVC’s junk-rated net debts and leases total £2bn, or 6.2 times the £322m it earned before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation in the year to March, according to figures that the company shared with lenders.

4. I find it inexcusable that IIFCL and NIIF, whose collective contribution to crowding in private capital (which would otherwise have not come) to infrastructure financing is negligible, are so miserly with sharing information about their projects in their website as well as their annual accounts. The starting point for good governance is information disclosure. Its absence is there to see in both institutions. See this blog post on NIIF.

5. The case for a "single price to be paid to vaccine makers for all the doses that they supply". This is a strong case against the just announced vaccine policy of the government of India.

I am not sure about the single price argument. But the case for canalising vaccines through public systems and even having it delivered only through government system is very strong.

It is being reported on SII's price,

Even the Rs 400 procurement price — applicable to both State and new Central procurement orders — is higher than the price at which governments in countries such as the US, UK and in the European Union are sourcing directly from AstraZeneca. It is also higher than the price agreed by countries such as Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and South Africa for supplies of the vaccine from SII. In most of these countries, the shots are being administered for free, with the governments absorbing the costs... In terms of per dose pricing, the 27-nation EU is paying $2.15-$3.50 for a shot of the vaccine across locations in Europe, a high-cost manufacturing destination. The EU had, incidentally, invested $399 million “at risk” in AstraZeneca way back in August 2020, in return for 400 million doses of its vaccine. The UK, which had a smaller investment commitment to AZ, is paying about $3 per dose and the US has been offered the vaccine at $4 per dose, according to data compiled by British Medical Journal. Both the US and the UK are paying the amount directly to AstraZeneca. Meanwhile, Brazil is reported to be paying $3.15 per dose for the AZ vaccine through state-owned Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), another licenced producer.

Bangladesh, according to Reuters, is paying an average of $4 per dose supplied by SII, with the BBC having quoted a health ministry official in Dhaka citing that it entails a total cost at $5 per dose, incorporating the margin charged by Beximco, the vaccine’s Bangladesh distributor. Both South Africa and Saudi Arabia had paid over $5.25 per dose from SII, according to UNICEF’s Covid Vaccine Market Dashboard, which collects publicly reported price information. This is higher than the price at which Indians will get vaccinated at state government hospitals, without subsidy.

This is unlikely to have a nice ending for SII.

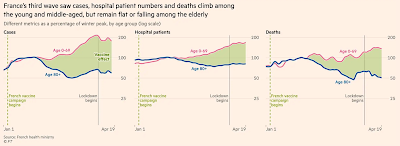

6. FT has a good article on the impact of vaccines. From UK

From France.From Chile.

It appears to be working.

It is also reported from a new UK study from more than 350,000 people between December 2020 and April 2021 that a single dose of either Oxford/AstraZeneca or Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines cut the rate of infections by around 65%, a second dose reduced by 70-77%, protected older and more vulnerable people almost as well as younger and healthier individuals, it took around 21 days after the first jab for the immune system to mount a decent response, and that vaccinated people could still re-infect and spread asymptomatic spread of the virus.

7. The conventional wisdom is that generous unemployment benefits discourage work and distorts the labour market. The Economist points to the contrast of Denmark which has the most generous unemployment benefits program and the best functioning labour market.

Danish benefits are worth more than 80% of previous earnings after six months out of work, compared with 60% across the rich world and less than 50% in Britain (America is even stingier). For Danish parents who lose their jobs, replacement rates can approach 100%. The generosity of Denmark’s unemployment system is the flipside of its liberal regulation of employment contracts—a combination called “flexicurity”. Danish employers can hire and fire workers pretty much as they please. Jobs therefore come and go, but people’s incomes are stable. Yet the state’s munificence has not produced a class of feckless drifters. Denmark’s unemployment rate is lower than the rich-world average and its working-age employment rate is higher. Long-term unemployment is low. When Danish people lose a job, they find a new one faster than almost anyone else in the world, according to the OECD.

This generosity comes with tough love

Denmark makes it hard for people to live off welfare. Recipients must submit a CV to a coach within two weeks of becoming unemployed. They can be struck off for not trying hard enough to search for work or to keep up with adult-education programmes. As a share of GDP Denmark spends four times as much as the average OECD country, and more than any single one, on “active labour-market policies” to make people more employable.

8. The work of the newest John Bates Clark medal winner, Isaiah Andrews, points to a much needed methodological correction to social sciences research.

In work with Maximilian Kasy, now of Oxford University, Mr Andrews cast light on the fact that economists are too eager to pursue striking results, and journal editors too prone to approve them. Studies that find that minimum wages have no significant effect on employment, for example, are only a third as likely to be published as those finding a stronger negative effect. The researchers developed a way to adjust reported results for this publication bias—and found that the average effect of a higher minimum wage on employment fell by half.Mr Andrews, with others, also explored what is called the winner’s curse when it comes to choosing between policies: the policy that performs best in a trial may owe its top rank to chance, and will later be doomed to disappoint. To illustrate this the researchers turn to a trial that assesses the most effective ways of encouraging people to donate to charity, by combining requests for specific donations with promises to match the initial contribution. The researchers find that if the charity chooses the method that does best in a trial, it will always overestimate its donations. They suggest ways to make a more realistic estimate that takes account of the role of chance.

Andrews' work reveals the deficiencies in the methods of economists and provides tools to correct them.

9. Finally, very informative interviews on the impact of the farm laws on agriculture processing.

There is a huge asymmetry in information, when you invisibilise transactions and players, businesses will have more information on the farmers through credit scores, data stats, but the farmers won’t have that much information on these businesses and that puts them at a disadvantage

1 comment:

Thanks for sharing that Harish Damodaran piece (https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/nabard-farmers-india-protest-agriculture-sector-7279331/). It is an analysis well done.

The diagnosis bears similarity (even many years later) to B R Ambedkar's. Here's an excerpt from his collected works (Source: pg 496/520 https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/attach/amb/Volume_01.pdf ) -

Does our agriculture—the main stay of our population—give us any

surplus ? We agree with the answer which is unanimously in the negative.

We also approve of the remedies that are advocated for turning the deficit

economy into a surplus economy, namely by enlarging and consolidating

the holdings. What we demur to is the method of realizing this object.

For we most strongly hold that the evil of small holdings in India is not

fundamental but is derived from the parent evil of the mal-adjustment in

her social economy. Consequently if we wish to effect a permanent cure

we must go to the parent malady.

But before doing that we will show how we suffer by a bad social

economy. It has become a tried statement that India is largely an

agicultural country. But what is scarcely known is that notwithstanding

the vastness of land under tillage, so little land is cultivated in proportion to her population.

Post a Comment