Gentrification is a uniquely housing market problem. It describes the phenomenon of lower-income inhabitants of an area being displaced directly or indirectly by higher-income residents during the process of regeneration or redevelopment of the locality. The desired development happens (and property prices go up), but at the cost of the existing inhabitants.

In the latest edition of Works in Progress, Anya Martin explores the issue of gentrification and writes about the surprisingly counter-intuitive evidence.

There is an apparent mystery in gentrification studies: many of them show very little displacement impact. One reason for this may be that poorer residents often exert huge effort to stay in place when rich new residents move in, because they too want to benefit from the additional amenities that come with this. Some studies show lower rates of evictions in neighborhoods considered to be gentrifying.

Moving is more often driven by personal conditions than neighborhood trends. Most people move a number of times throughout their lives because of changes to what they can afford, where they work, or how much space they need. Poorer people move at especially high rates, regardless of whether or not their neighborhood is gentrifying. Even in neighborhoods that are a long way from being gentrified, the most disadvantaged people are frequently forced to move away from their communities by unfortunate circumstances and the demands of their landlords. This high background churn helps explain why existing residents do not seem to move much more out of neighborhoods seeing rising numbers of college-educated residents and increasing house prices – that is, places that are gentrifying – than others. The base rate of people moving out is already high. For example, according to a 2019 study in the USA 60 percent of lower-educated renters move out of non-gentrifying areas in any ten year period, while 66 percent move out of gentrifying areas.In other words, the vast majority of these movers are moving because of their own personal circumstances, not because of gentrification per se. The study also finds that the people who do move tend to move to neighborhoods with similar characteristics to their old one – there isn’t a clear pattern of people downgrading to less desirable neighborhoods.

But the displacement while generally small across the US, is likely to be significant in cities with limited supply and large demand, and large differential between prices and construction costs. In these cities, invariably some of the biggest metropolises, the renters tend to get pushed out of gentrifying areas and to neighbourhoods with lower school quality and higher crime rates. However, low-income homeowners tend to remain and benefit from the higher prices.

The nature of the demand across market segments in the housing market in large cities (where supply is generally scarce) is such that any marginal supply will invariably get absorbed by the most well-off in those respective market segments. In fact, given the exorbitant housing costs (property prices and rents) in most global cities, it’s perhaps not incorrect to say that any marginal supply in any market segment will be unaffordable for all but the well-off.

Even with well-meaning redevelopment programs that try to keep the incumbents in the area, it’s almost impossible to prevent the existing inhabitants from selling out and relocating to a less expensive area or suburb. In other words, regeneration and gentrification tend to go together. While I cannot point to studies, I’m inclined to believe this is the likely trend in most cities across the developing world.

But this does not make the case against redevelopment, for the absence of regeneration creates a vicious spiral of immiseration. The neighbourhood remains entrapped in its poor quality of infrastructure, services, retail traders, jobs, and quality of life. Some level of gentrification (and associated displacement) is therefore desirable to create the conditions that can trigger improvements in these areas. But controlling gentrification to limit displacement can be daunting.

Housing colonies in the better-off (or central parts of cities) areas will always struggle to retain the original allottees. Certain conditions and safeguards only delay the inevitable displacement.

In theory, increased supply due to redevelopment, even with displacement, should set in motion a cascade of demand-supply dynamics across the entire housing market. But in practice, as I have blogged here, there’s a strong possibility that the shifts in the housing market are confined to the top end. It’s likely that on the net, like with free-trade, regeneration and gentrification end up leaving the incumbents worse-off.

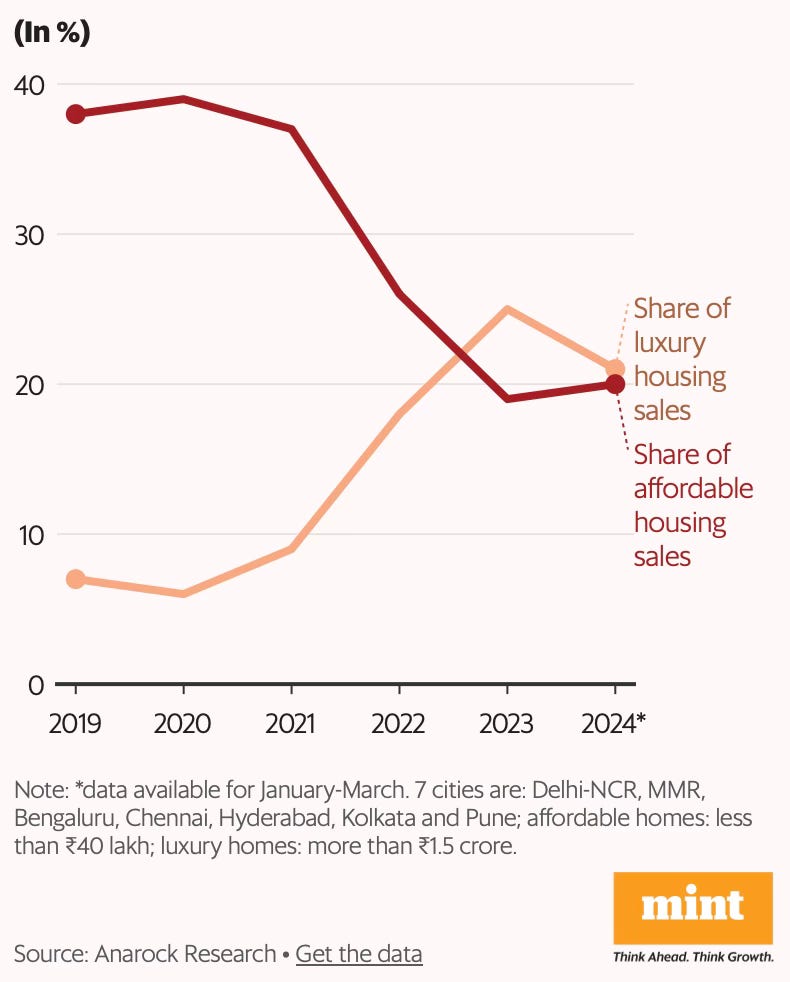

Consider the latest data point from India, where even as the property market enjoys a boom, the sales of affordable housing units (below Rs 40 lakh) have been declining over the past five years in top cities.

While home sales climbed sharply from 2019 to 2023, the share of affordable housing dropped from 38% to 19% during the period. In January-March of 2024, the sales share stayed flattish, at 20%. Not just sales, budget housing supply or new launches too shrank from 40% to 18% in the same period. The decline of affordable housing became increasingly apparent after the pandemic, as larger, premium homes gained favour... the sales share of luxury homes jumped from 7% in 2019 to 25% in 2023. In January-March 2024, this was at 21%, but it is expected to pick up during the year. Of all the cities, Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) has seen the most traction in this segment.

The biggest Indian cities do not have a market-driven supply problem for upper middle-income and high-income housing. The market supply problem is confined to the affordable housing and lower-income housing. And that has been the case for years. For the lower income housing segment, given the exorbitant land prices in cities, some form of subsidised housing can be the only solution.

Ultimately the only strategy to mitigate gentrification is to ensure any regeneration comes with a sharply increased supply.

If supply is elastic enough, new housing can alleviate or even prevent the forces that push existing residents out of an area. The more new homes you have, the more rising demand from higher-income movers can be absorbed, and the more low-income households are able to trade up into better housing. This can feel counterintuitive to many, because nothing looks more like gentrification than new-build housing, which is typically built to higher standards than existing stock. But if new higher-income residents want to move to an area – for work, education, family, or simply because they themselves have been priced out of somewhere else – and they aren’t moving into new builds, then they outbid others for existing stock.

Further, gentrification can have fascinating longer term consequences.

Using the Finnish whole population register, Cristina Bratu, Oskari Harjunen, and Tuukka Saarimaatracked who moved into newly built units and, crucially, who took the homes they left. They found that while newly built homes were initially occupied by higher-income households, this triggered moving chains where middle- and lower-income families eventually moved into the higher-quality homes that had been freed up by the higher-income ones. Even more interestingly, while the first residents of newly built homes were often higher income, after those first inhabitants moved out, the newer homes were then occupied by those on lower incomes. Ultimately the study finds that for every 100 new centrally located market units that are built within a neighborhood, 66 become available for below-average-income households through vacancies within just two years. Far from pushing lower-income households out, the new homes make space for more of them.

Since 2018 London has been experimenting with a scheme for the regeneration of social housing estates (owned by local government or housing associations) where residents can vote to go for redevelopment.

These estate ballots give current social housing tenants and owners of homes on the estate a choice of whether they would prefer things to stay as is, or whether they would prefer a brand-new – and usually larger – apartment or house on a new estate. The quid pro quo is potentially years of disruption while it is built, as well as hundreds or thousands of new private renters or homeowners moving in next door – the cost of the regeneration is funded through the development of new homes which are sold or let privately. Estates can increase enormously in density: in Tower Hamlets, affordable housing provider One Housing is redeveloping 24 homes into 202, of which 50 percent will be rented at below-market rates. All 24 existing households will get new, higher-quality homes, and 84 percent of residents approved the proposals with 100 percent turnout. In Lambeth, 135 homes are being redeveloped by Riverside Group into 441 larger and higher-quality homes, of which almost half are submarket. This was approved by existing residents at 67 percent with an 87 percent turnout. The development comes with not only new homes, but new amenities like a gym, a community center, cycle parking spaces, and a new communal outdoor space.

Such regeneration schemes of slum redevelopment (and squatters on public lands) have been widely attempted in Indian cities but with limited success. Their failures have to do with difficulties in distinguishing between house owners and tenants, lack of agreement among residents resulting in litigations, poor or inadequate temporary accommodation facilities, exploitation by local builders and developers in cahoots with politicians and officials, delays in construction and handing over, poor credibility of governments, and so on.

A big challenge in adopting the UK’s social housing redevelopment model is the high density of slums in countries like India. For a start, given the low prevailing per capita space, accommodating all the residents and also finding enough units for commercial sale becomes difficult. This is further exacerbated by the large number of tenants. Indian slums, especially in the largest cities, are characterised by heavily overcrowded housing units with multiple tenants in one room itself. Further, once a proposal is floated to redevelop the slum, several new tenant claimants emerge.

Though governments typically try to address the problem by mandating that only those residing before a cut-off date and for more than a certain number of years are eligible, its validation runs into several practical difficulties. The claims and counter-claims invariably get entangled in the local politics, thereby making it difficult to move ahead.

My earlier posts in this series are here, here, here, here, here, and here. This is an earlier post on the issue of slum redevelopment in the context of Vijayawada.

No comments:

Post a Comment