1. For all practical purposes Apple appears to be a Chinese company. Tim Cook has ensured the near complete surrender of the company to the Communist Party. Jay Newman writes in FT Alphaville that the biggest driver of its share price may be the close relationship Cook has cultivated with China.

Entente cordiale with the Chinese Communist party affords Apple a charmed existence when it comes to manufacturing and selling products in China... Cook has embedded Apple ever deeper in China over the past 20 years. After inking a secretive 2016 agreement to invest $275bn in China’s economy, workforce, and technological capabilities, the iPhone became a best-seller. In reality, Apple is now as much a Chinese company as it is American. Almost a fifth of its revenue comes from sales in China, and operating profits in greater China — Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and the mainland — topped $31.2bn in 2022. That’s a hefty chunk of Apple’s earnings (though given the near impossibility of getting large sums out of China, those profits may not even be money good). Apple provides more than cash and intellectual property. Relations are enhanced by the credibility Apple’s brand bestows on a repressive, autocratic state, and the (cough) flexibility it demonstrates in supporting CCP objectives. When it comes right down to it, Apple just can’t say no...Apple is tiptoeing — frantically — towards the exit: moving production of iPhones to India, AirPods to Vietnam, Macs to Malaysia and Ireland... But these efforts seem futile: Apple likely will never be able to completely exit China. Even small shifts risk retaliation by Chinese overlords who might retaliate by turning Chinese consumers against Apple products. Will China — which has contributed hugely to Apple’s success — allow it to slink away? Why would they? These are problems Apple made: for the foreseeable, Apple has no choice but to do what China wants.

I would not be surprised if Apple becomes an example of how corporate greed and lack of foresight brought about the downfall of the world's largest company and its most famous brand.

2. In another article Newman and others points to the problem of US companies in China not being able to repatriate their profits back.

As a practical matter, from the perspective of capital investment, that makes China a roach motel: you can get money in, but you can’t be sure of how, when, or at what value you’ll be able to get it out. The renminbi isn’t freely convertible. So, as a threshold matter, Chinese regulators not only control the price of the currency but, implicitly, the value of investments. More important: withdrawal of capital and the repatriation of profits through dividends are discretionary. Chinese law forbids anyone from sending more than $50,000 out of China in any given year without government approval, and the Chinese state controls an extensive bureaucracy that administers those rules. If the CPC is feeling anxious about hard currency reserves, the payment of dividends to foreign investors may not be its highest priority. And, if a sanctions regime against China or Chinese entities expands further, all bets are off... There is nevertheless an argument for Western companies’ Chinese cash to be viewed as a stranded asset — and accounted for as such. In the event of a hotter Cold War, foreign investments in China could be held hostage, and the ability to repatriate significant amounts of capital could devolve, without much warning, into coerced transfer of technology and a geopolitical quagmire.

Even without much evidence as to how much Chinese revenues actually contribute to the bottom line, financial markets appear to prize it. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest Western investors ascribe significant value to Chinese revenue on the books of Western companies — far more than the value ascribed to equivalent sales by their Chinese counterparts. A simple price-to-sales ratio points to Chinese revenues booked by Western companies being worth 50 per cent more than they would be on the books of Chinese entities...

Through the magic of arbitrage, international capital markets can be used to transform Chinese revenue from indistinct income statement entries into opportunities for Western executives and shareholders to sell their shares on American and European stock exchanges. Stranded revenue from sales within China has been a boon to the share values of Western companies: illusory Chinese renminbi have become dollars and euros.

It's only a matter of time before the high valuations of US companies investing in China would revert to their true valuations. Apple may be the biggest loser.

3. In a definitive break from the past, the US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan made it clear that it's not the US Government's responsibility to protect US business interests in China, thereby signalling a clear discouraging of US business investments in that country.

“Our priority is not to get access for Goldman Sachs in China,” Sullivan said at the White House. “Our priority is to make sure that we are dealing with China’s trade abuses that are harming American jobs and American workers in the United States.”

4. Europeans tighten scrutiny of Chinese investments in Europe

Chinese investment into Europe fell to its lowest point in almost a decade last year as European countries tightened rules to stymie a slew of Chinese acquisitions. The 22 per cent decline in investment in 2022... reflects Europe’s recent moves to police the sale of assets to China after years of enthusiastically courting investment from Beijing. The researchers found that at least 10 out of 16 investment deals pursued in 2022 by Chinese entities could not be completed in the technology and infrastructure sectors, principally because of objections raised by authorities in the UK, Germany, Italy and Denmark. Several of the aborted deals, such as proposed semiconductor acquisitions in Germany and the UK, were blocked following reviews into the specific technology targeted by the Chinese investor... The overall level of Chinese investment into the EU and UK declined 22 per cent to €7.9bn in 2022, the report said. The level of investment was a fraction of the €47.4bn recorded in 2016 and the lowest total recorded since 2013. The totals include investment into new operations as well as mergers and acquisitions.

5. The Chinese government has made it an art to say one thing in public and pursue another thing in private. The latest is the efforts to woo back private investments being accompanied by restricting access to information and raids on foreign companies. Sample this about raids on the expert network group Capvision which was shown primetime on national television,

Capvision specialises in connecting international investors and management consultants, such as those from Bain and McKinsey, with its network of 450,000 subject specialists. More than 500 of the 700 employees of the company, which was founded in 2006, are based in the mainland, according to public records... Billed by state media as part of a nationally co-ordinated campaign to clean up the consulting industry in the world’s second-largest economy, it follows other raids in recent weeks on blue-chip US firm Bain & Company and due diligence group Mintz. The campaign is making it more difficult than ever for foreign investors to glean even basic information on potential acquisitions, Chinese partners or suppliers. That is at least partly by design as Beijing also methodically curtails foreign access to once openly accessible public data such as academic theses and business ownership records. The clampdown comes despite a charm offensive by Li Qiang, China’s second-ranked leader after President Xi Jinping, to woo foreign and private investors back to the country after coronavirus pandemic controls crushed growth last year...The clampdown on expert networks comes as China has cut off foreign access to data, ranging from shipping transponders that relay global supply chain information in real time, to public databases. Last month, the country’s largest academic database CNKI, home to university theses, dissertations and other academic papers, began blocking foreign access. Private and government-run databases with Chinese corporate information, patent information, court records and procurement tenders have also snapped shut.

These raids and their public screening have been sought to be rationalised as over-kills by the lower level bureaucrats on directions from the top. To an extent lower level bureaucrats tend to overdo stuff. But in a tightly run ship as China is, if the over-kills end up hurting the purpose of the leadership to attract back foreign investors then it's difficult to believe that they would not rein in such overkills. Besides, the airing of the raids on primetime television should leave us in no doubt about the intentions of the Chinese authorities to send out a strong message to its own citizens against sharing any information with foreigners.

Beijing believes that it can pull off the contradictory actions of wooing investors on the one side while undertaking raids and clamping down on ease of doing business for foreigners, because it feels foreign investors are greedy and short-sighted and will collectively overlook such actions when wooed individually by the Chinese government.

See also this long read on how restrictions on travels and information access is making it difficult for Americans to understand the latest trends and issues in China.

6. Rana Faroohar has some numbers on China's concentrated market power in important sectors,

According to a 2022 US-China Economic and Security Commission review, 41.6 per cent of US penicillin imports came from the country, which also has 76 per cent of global battery cell manufacturing capacity within its borders, 73.6 per cent of permanent magnets (a critical component of electric vehicles), and from 2017 to 2020, supplied 78 per cent of US imports of rare earth compounds.

Given the pervasive concentration in markets, Faroohar writes

I’m beginning to think that we should institute a new market principle that Barry Lynn, the head of the Open Markets Institute, an antimonopoly think-tank in Washington DC, calls “a rule of four”. In crucial areas, from food to fuel to consumer electronics, critical minerals, pharmaceutical products and so on, no country or individual company should make up more than 25 per cent of the market. What’s more, countries should apply this rule both locally and globally.

7. Quiet transformation in the Business Process Outsourcing sector in Philippines.

Before the pandemic, 75% of the Philippines’ IT professionals worked in Metro Manila—the centre of BPO companies since the early 1990s. Now, it’s down to 50%, according to real-estate services provider KMC Savills... In 2022 alone, it generated a revenue of US$32.5 billion, more than 8% of the national GDP... The exodus is spreading BPO facilities across the nation as prospects for growth emerge in other regions... The migration from Manila started in 2020. However, the homecoming of workers has accelerated only recently... In 2022, 31% of BPO jobs were located outside Manila, 17 percentage points higher than in 2021... BPO companies are relocating because of a basket of reasons. One main motivator is that their staff have stronger spending power outside of Manila, and costs for those operators are lower in other major cities. It’s an equitable situation for everyone involved. Meanwhile, a new breed of companies—knowledge outsourcing process services like animators, game developers, and telehealth providers—is slowly filling in the physical void left behind by BPOs that have departed Manila... KPO service providers handle tasks that cannot be automated and require more specific skill sets, such as animation, game development, and telehealth.

8. More signals of worsening trends in American health care industry. This time NYT reports that large corporations and health insurers are gobbling up small primary health care practices.

CVS Health, with its sprawling pharmacy business and ownership of the major insurer Aetna, paid roughly $11 billion to buy Oak Street Health, a fast-growing chain of primary care centers that employs doctors in 21 states. And Amazon’s bold purchase of One Medical, another large doctors’ group, for nearly $4 billion, is another such move. The appeal is simple: Despite their lowly status, primary care doctors oversee vast numbers of patients, who bring business and profits to a hospital system, a health insurer or a pharmacy outfit eyeing expansion... The growing privatization of Medicare, the federal health insurance program for older Americans, means that more than half its 60 million beneficiaries have signed up for policies with private insurers under the Medicare Advantage program. The federal government is now paying those insurers $400 billion a year... It’s a one-stop shop for all your health care dollars...The absorption of doctor practices is part of a vast, accelerating consolidation of medical care, leaving patients in the hands of a shrinking number of giant companies or hospital groups. Many already were the patients’ insurers and controlled the distribution of medicines through ownership of drugstore chains or pharmacy benefit managers. But now, nearly seven of 10 of all doctors are either employed by a hospital or a corporation, according to a recent analysis from the Physicians Advocacy Institute. The companies say these new arrangements will bring better, more coordinated care for patients, but some experts warn the consolidation will lead to higher prices and systems driven by the quest for profits, not patients’ welfare.Insurers say their purchase of medical practices is a step toward what is called value-based care, with the insurer and doctor paid a flat fee to care for an individual patient. The fixed payment acts as a financial incentive to keep patients healthy, provide more access to early care and reduce hospital admissions and expensive visits to specialists. The companies say they favor the fixed fees over the existing system that pays doctors and hospitals for every test and treatment, encouraging doctors to order too many procedures.Under Medicare Advantage, doctors often share profits with insurers if the doctors take on the financial risk of a patient’s care, earning more if they can save on treatment. Instead of receiving a few hundred dollars for an office visit, primary care doctors can be paid as much as $14,000 a year to manage a single patient.

More evidence of the corrosive effects of private equity in health care. Envision, a hospital staffing company owned by KKR is lurching towards bankruptcy after "crumbling under the weight of a $7 billion debt load it accumulated as part of its 2018 buyout".

10. TT Ram Mohan examines the US Federal Reserve's report on the Silicon Valley Bank failure and draws lessons for India

The RBI's... intrusive approach is a better safeguard for banking stability than the light touch elsewhere. However, supervision can only be a third layer of defence against bank instability. Regulations are the primary layer, followed by the board. The RBI must find ways to get bank boards to do a far better job. A radical change would be to alter the way independent directors are appointed at banks. At present, the promoter or CEO has the dominant say in the appointment of independent directors (at both private and public sector banks). The RBI may want to insist that, for instance, one independent director be chosen by institutional investors and another by retail shareholders (from a list of names proposed by the Financial Services Institutions Bureau). Until we have independent directors who are distanced from the promoter and management, it’s unrealistic to expect board oversight to improve.

The RBI is hosting a conference for bank directors later this month. Here are two suggestions. One, in the interests of transparency and accountability, the RBI may want to commission a review of the failures at IL&FS and Yes Bank. Two, it may prescribe the FRB’s review of SVB’s failure as one of the “readings” for the conference. It may also include the report of the UK’s Financial Services Authority on the failure of Royal Bank of Scotland during the GFC. At least, bank directors can’t say they weren’t warned.

11. Latest data from the implementation of the IBC

According to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI), 611 insolvencies that yielded a resolution plan by the end of December 2022 took, on average, 482 days. Similarly, about 1,900 cases that went for liquidation took, on average, 445 days. There is clearly a need to reduce the amount of time taken to resolve insolvencies.

12. India warehousing market facts of the day

India’s warehousing stock of grade A and B facilities has grown to 330 million sq ft today, from 140 million sq ft in 2017, according to estimates by JLL, a property advisory... The US added 333.8 million sq ft of new warehousing space in 2022 alone—that’s higher than India’s overall warehousing stock as of now... ... while 51.8 million sq ft of warehousing space was leased in 2021-22 in the eight primary markets, through grade A and B warehousing, another 15 million sq ft was leased across India’s 13-15 secondary markets.13. Vivek Kaul points to the latest data set on India's small consumption class,

As the Indus Valley Report 2023published recently pointed out, 1% of Indians take 45% of flights, 2.6% of Indians invest in mutual funds, 6.5% of users are responsible for 44% of UPI transactions, and 5% of users account for a third of the orders placed on Zomato. As Zomato recently reported: “Customers with annual order frequency >50 as a % of annual transacting customers have increased from 1.4% in 2018 to 4.7% in 2022." Basically, this means around 5% of Zomato’s customers order from it at least once a week. So, as the Indus Valley Report points out: “Much of the consumption is driven by a tiny super-user set… [The] broad user base narrows sharply when it comes to paying users."

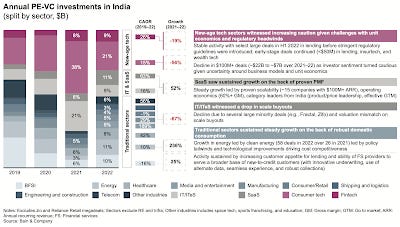

This is the Indus Valley Report 2023 mentioned. This graphic is interesting and highlights the point about the small consumption class.