I had blogged here with some early thoughts on Trump 2.0 and had said that I’ll revisit them as the administration progresses. This is a six-month stock taking.

It’s now clear that Donald Trump is single-handedly redrawing the economic and political map of the world. The former (economic) is already done, and the latter (political) must follow in due course. While there’s some clarity on the contours of the former, though its long-term consequences may still be uncertain, the impact on the latter may be slower in emerging and likely more profound.

Whatever its merits and however vague the trade deals, he has managed to bully and arm-twist almost the entire world to unilaterally open up their economies; accept an unthinkable level of high tariffs on their exports to the US; commit to purchase vast quantities of US goods like oil, gas, and arms; and commit hundreds of billions of dollars in manufacturing and other investments in the US. The abject surrender by the EU’s 27 members after holding out initially for zero-for-zero tariffs, exemplified by Ursula Von Der Leyen’s virtual prostration before Trump at Turnberry, Scotland, will remain as the totemic moment in this regard.

He forced America’s NATO allies to voluntarily commit to raising their low shares of total defence expenditures to 5% of GDP, including 3.5% of GDP for core defence requirements, by 2035. And the European allies have already started taking action in their budgets.

Not even the most imperial and colonial of powers and kings/rulers could have wrested such commitments. And all this has been done without a bullet being fired or a bomb being dropped. It would have been unimaginable for anyone to think that a single man’s bully diplomacy could have brought the entire world to its knees without even a fight. Countries have reluctantly acquiesced into these egregiously one-sided trade deals on the simple belief that it’s better to strike these deals than suffer greater damage from tit-for-tat tariffs. Such has been the fear generated by one man that leaders globally have refrained from publicly criticising or contradicting him.

In this respect, the first six months of Trump 2.0 are enough to be described as the most imperial moment in world history. Previous imperial kingdoms held sway over small parts of the world, but this one rules over the world as a whole.

The FT’s Robert Armstrong coined the delicious phrase, Trump Always Chickens Out (TACO), to describe the US stock market’s surprising calmness in the face of Donald Trump’s capricious policies. This needs to be qualified. TACO applies only when there’s a match on the other side. The bond markets and China are two standout examples. Even those like Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum and Canada’s Mark Carney, who have kept their card close and refused to play the Trump-pleasing game, have managed to keep Trump guessing. But in all those cases (except perhaps the UK) where countries have gone overboard in trying to please him, he has slapped tariffs and wrested other commitments. All this only confirms the adage that a bully always wins against those who do not stand up to him. Sadly, world leaders, at least for now, have sought to acquiesce rather than fight.

While the immediate economic impact of these policies in the US is most likely a recession and higher prices sometime next year, their medium-term consequences for the US economy could, on balance, even be beneficial. This is perhaps the most optimistic scenario for the US economy. For a start, even after Donald Trump leaves and even if a Democratic administration emerges, some of these tariffs will likely stay. The regime that emerges will surely rebalance the currently lop-sided nature of the Trump trade deals. But even after the most optimistic (for the US’s trade partners) revisions, it is likely to remain in favour of the US. In other words, Trump 2.0 may have conferred a big long-term advantage to the US in its international trade relations.

The reshoring of manufacturing, in some form or other, is a train that has started. Multinational corporations have been forced into shedding their exclusively efficiency-maximising business models and adopting strategies that build resilience through supply chain diversification, ideally by reshoring to their home bases. The US economy will collect three to five times more revenue from tariffs (from the current monthly collection of about $8 billion, it’s already over $30 billion), and it’s likely to play an important role in financing the country’s burgeoning fiscal deficit. Unfortunately, these significant revenues once tasted by the US fiscal system will create incentives to perpetuate even after Trump leaves.

A high-level perspective is that the world economy has enjoyed windfall gains since the 1990s from trade liberalisation and the WTO. Tariffs have fallen spectacularly to historic and, perhaps, undesirable lows. After all the sectoral and country-specific carve-outs and dispensations, and general renegotiations that will happen in the coming months, the Trump tariffs may calibrate tariffs to more realistic levels. That may be a good economic outcome.

But there are many aspects of the other side of the ledger that are unmitigatedly bad for the US and its allies. For a start, the commitments given by countries on the purchase of US goods and investments in the US are most unlikely certain to not materialise in any meaningful manner. It’s most likely that all countries will drag their feet on these commitments, preferring to wait out the Donald Trump regime by allowing for some cosmetic and politically expedient wins for him.

All the deals are filled with fantastical investment commitments, all of which are too impossible to comply with. Investment decisions are with corporates and are done purely on commercial considerations. No government (except perhaps the Chinese) can force its corporations to make investment commitments just to meet some national foreign policy obligations. And given the commercial viability challenges associated with reshoring manufacturing to the US, coupled with Trump’s whimsical nature, very few companies would be willing to bite the bullet. Besides, given that investment decisions can take years to materialise, countries and companies will wager that it’s a smart thing to make some vaguely worded “commitment” and get the tariffs out of the way. One can always renegotiate, if needed, or, more likely, Trump will move on to other things, and domestic political and geopolitical trends will dissipate the commitments.

Ironically, the vagueness of the trade deals may have been the convenient escape clause that made it alright for countries to agree to deals with the US and present Trump with ego-boosting wins. The deal with EU is filled with feel-good triumphs with little substance. This article illustrates how the EU conceded on the (politically and substantively unimportant) imports of lobsters and bison meat but refused to concede on the more substantive issue of imports of hormone-raised beef and acid-washed chicken.

Several of the incentives the European Union used to clinch the agreement may look like gifts, but if so, they are gifts unearthed from the back of the closet, dressed up in nice wrapping paper and topped with a fancy bow. They look good, but they did not cost Europe much. Take Europe’s promise to buy $750 billion in energy. That number is spread across three years, and it includes Europe’s existing purchases of American gas and oil, expected future additional purchases and anticipated investments in things like nuclear infrastructure by American companies in Europe. But while the European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, can estimate how much European companies might spend, those decisions are up to the private sector. The European Union cannot force businesses to buy American energy if the math does not make sense. Likewise, the bloc’s promise to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in the United States is a tally of expected spending from European companies. It is simply an expectation of how much money could flow toward America, not even a commitment of how much will.

With time, they might get exposed as mere Pyrrhic victories that stoked the President’s vanity without achieving much in substance.

The geopolitical consequences of these policies will be felt in the months ahead. Credibility and trust, built over decades of painstaking work, can erode spectacularly in a few months of flippancy, capricity, and unreason. Thanks to just six months of Trump 2.0, America may have significantly and irreversibly eroded its soft power in diplomacy and in shaping global institutions. The example of India-US strategic relationships (more later) is a case in point.

Further, it has surely brought together other like-minded blocs and countries like the EU, non-US G7 economies, India, Japan, East Asian economies, Brazil, Mexico, and others in shaping global institutions in a manner that derisks them from not only China and Russia, but also the US. In areas like acceptance of the dollar as the reserve currency and reliance on the US-controlled SWIFT payments system, Trump 2.0 has surely set afoot efforts even among allies to diversify away from the control of the US. Similarly, efforts to create harmonised global regimes on areas like data localisation, AI, taxation of multinational corporations, green transition, and so on, are likely to further isolate the US from its allies. In simple terms, for the vast majority of countries, Trump 2.0 may have pushed the US into the group of antagonists currently populated by China and Russia.

This mistrust of the US will get amplified as Trump expands his agenda beyond reshoring jobs and cutting trade deficits, to interfering in the domestic political issues of countries, like those happening with South Africa (supporting white settlers), Brazil (opposing the judicial process against Jair Bolsonaro), and Canada (opposing its moves to recognise Palestinian statehood). He has shown an increasing appetite to use the instrument of tariffs to meet not only economic goals but geopolitical and diplomative interests.

A test case will be the outcome of the scheduled Trump talks with Putin in Alaska later this week, which threatens to divide Ukraine without its consent. In his vanity to claim credit for stopping the war, Trump may well agree to Putin’s demands that the US recognise the cession of Crimea and the Eastern Donbas region, and freeze the current battle lines as permanent boundaries. If something like this happens, Ukraine is unlikely to agree, and it may well be a defining moment in the US-EU relations. Indeed, the European Commission, France, Italy, the UK, Poland, and Finland have already issued a strongly worded statement that opposed any backroom deal done without Ukrainian representation that compromised Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

The joint statement from the European Commission, France, Italy, the UK, Poland and Finland also said “the path to peace in Ukraine cannot be decided without Ukraine” ahead of a meeting next week between Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin… Late on Saturday, the European leaders released a joint statement calling for “robust and credible security guarantees that enable Ukraine to effectively defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity”. It added that “we remain committed to the principle that international borders must not be changed by force”… There is particular anxiety that Trump could seek a quick resolution to the war by offering Putin territorial concessions, legitimising its illegal annexation of Crimea and occupation of huge parts of four mainland regions of Ukraine: Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.

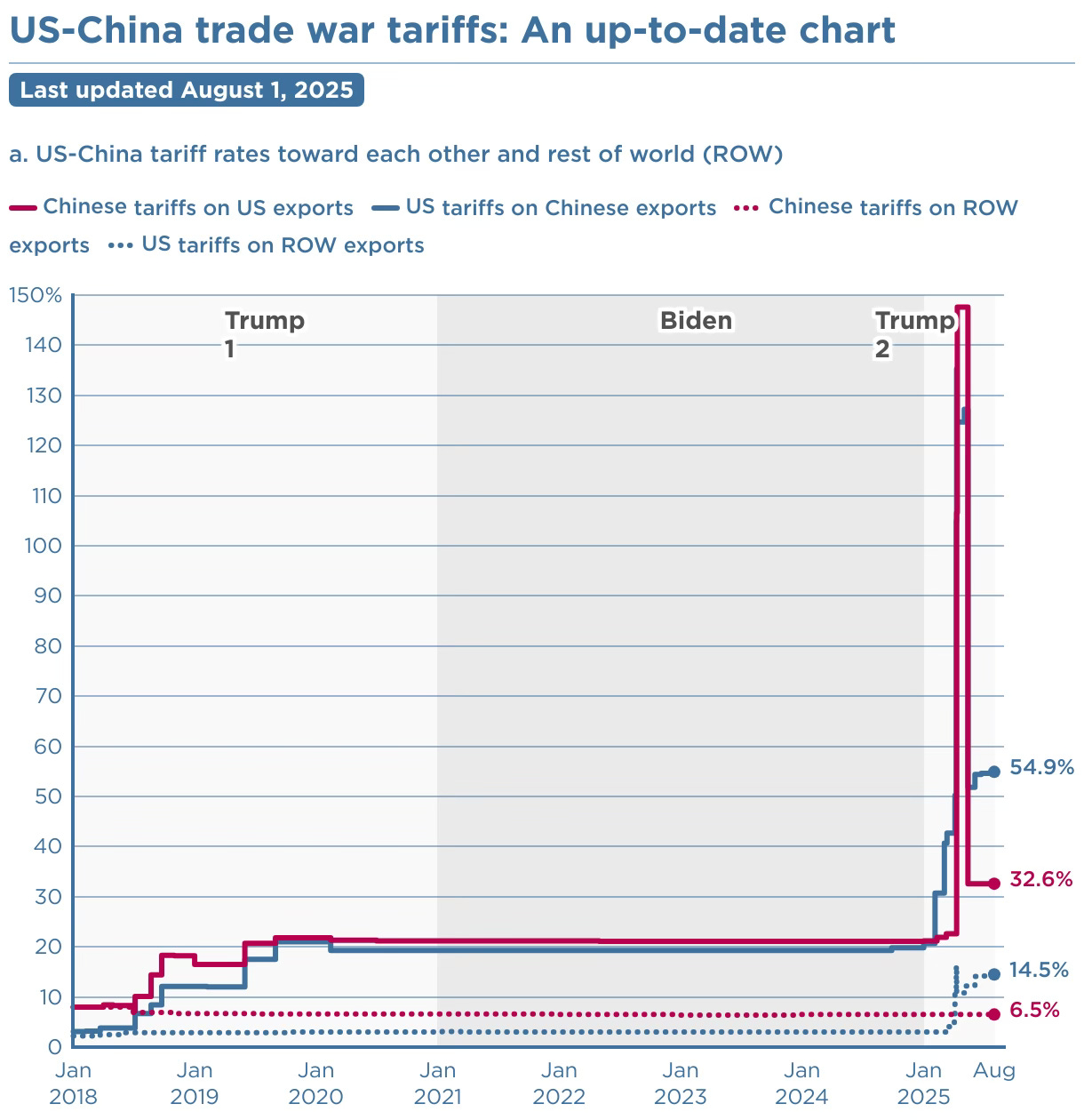

The biggest surprise in Trump 2.0 to date has been his actions on China. What started with the big bang tariffs on China(amounting to the highest reciprocal tariffs) is now giving way to perplexing about-turns. For a person prone to instant provocation, he has been inexplicably considerate with the Chinese. He condoned China’s tit-for-tat retaliation on his tariffs and agreed to an interim deal that marked a sharp climb down in lowering the tariffs on China from 145% to 55% and allowing China to retain a 33% tariff on US exports. It’s almost like Xi Jinping is doing to Trump what he’s doing to all others!

It says something about the reversal of Trump’s initial aggression on China that the Trump administration has imposed higher tariffs on close allies like Canada, India, Taiwan and Switzerland than on China.

More importantly, the interim trade deal ended up allowing the Chinese to link the relaxation of their newly introduced export restrictions on rare earth elements with those on Biden-era US export restrictions on Nvidia chips, instead of being confined to negotiating on lowering the succession of prohibitive tariffs. In simple terms, the Chinese got both lower tariffs and, more importantly, relaxation of export of Nvidia chips. Trump 2.0 and its scattershot tariff policies have taken the foot off the pedal in the Biden administration's strategy of progressively tightening access to strategically important technologies for China.

There’s now the real danger that, in his desperation to clinch a high-profile trade deal with China, Trump may relax Biden’s 2024 ban on exports of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips. The Chinese appear to consider this more important than even the H20 chips since they seriously constrain the ability of their companies, like Huawei, to develop their own chips. Memory chips are a critical part of AI chips which package together memory and logic chip components. In order to avoid hurting trade talks, the Commerce Department has already been directed to freeze further technology export controls to China. He now appears to be veering towards allowing the sales of Nvidia’s advanced Blackwell chips, and all that for a 15% share of the revenue from their sales.

The refusal to allow Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te to transit through New York en route to Latin America to pre-empt the issue from becoming an impediment to any trade deal is a massive strategic concession that undermines deterrence in the Taiwan Straits and signals a desperation that would have pleasantly surprised and gladdened the Chinese. What does it say about Trump’s strategic priorities when he extends the tariff deadline for China, apparently America’s primary geopolitical rival, even as he slaps India, one of America’s main ally in Asia, with two successive 25% tariffs, which take the total tariffs on India to nearly double that on China (30%)?

Now, even as Trump has harshly penalised India for buying Russian oil, he seems to be turning a blind eye to China, despite it being the single largest buyer of Russian oil since the Ukraine invasion and the second largest current buyer. More inexplicably, if punishing Russia is his objective, Trump appears not to be even concerned about the fact that China does far, far more to prop up the Putin regime than anything anybody else may be doing.

For all these reasons and more, I agree with Edward Luce, who has described Trump as the “last China dove in Washington”.

In the final analysis, I think there are only two bulwarks against Trump 2.0. The strongest bulwark is still the financial markets, especially the bond markets. The bond vigilantes can pile pressure on the dollar and, more importantly, drive up borrowing costs for the US government, and its corporates and households. As we have already seen, a poor response to a Treasury Bond auction can spook the markets as a whole and force hard choices on even Donald Trump. As an example, the bond market reaction to Treasury auctions was an important contributor to Trump pausing his exorbitant reciprocal tariffs in April 2025. The equity markets don’t have a similar restraining effect on Trump.

The other restraining force is that of the elites in corporate America. It’s no surprise that even amidst all the tariff increases, the likes of Apple and Nvidia have managed to obtain carve-outs, sparing them not only from the worst of the tariffs but even carry out business as usual. This is a good description of how lobbying to protect Nvidia’s commercial interests trumped even strong opposition on concerns about compromising national interests.

The H20 has become the focus of a debate between security officials who say allowing China to buy the H20 will help its military. But Nvidia argues that blocking US technology exports forces China to accelerate innovation. The Financial Times reported last week that 20 security experts, including Matt Pottinger, deputy national security adviser in the first Trump administration, and David Feith, who served at the National Security Council earlier this year, wrote to commerce secretary Howard Lutnick to urge him not to allow H20 sales to China. In the letter, the security officials said the move would be a “strategic mis-step that endangers the United States’ economic and military edge in artificial intelligence”.

Nvidia countered that the criticism was “misguided” and rejected the argument that China could use the H20 to enhance its military capabilities. Nvidia took a $4.5bn hit in the July quarter, as well as an additional $2.5bn in missed sales, after the White House introduced the original licence requirement… It was viewed as a ban that would kill the legal sale of Nvidia’s AI chips in China, cutting the company off from a market that Huang has said will hit $50bn in the next two to three years. The company had forecast an $8bn loss in China revenue for the July quarter.

Trump policies on deregulation, taxation, and economic diplomacy have promoted the interests of Big Tech and Big Finance. All talk of draining the swamp and clearing powerful entrenched interests in Washington has gone out of the window. While they may be willing to concede on secondary issues, when their core interests are threatened, it’s most likely that elite corporate interests will lock arms and resist. Besides, Trump himself, being a member of the elite corporate interests, would not go beyond a certain line in draining the swamp.

Among all countries, the difference between the expectations (at least in India) and reality from Trump 2.0 to date may well be the greatest for India. It was expected that Trump 2.0 would help cement the anti-China alliance between India and the US, and India would enjoy the collateral benefits from the US squeeze on China. Besides, it was believed that the natural affinities and other factors would help forge a tight relationship between the two countries. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, things have gone astray.

While the tariffs are very high and doubtless economically damaging for India, I’m inclined to feel that it is likely that their effects are being overestimated. For a start, there are several carve-outs, and they will most likely only increase over time as interest groups emerge in the US and start lobbying, and the tariffs themselves will most likely get renegotiated downwards. For example, a Trump-Putin deal later this week can eliminate the 25% punitive tariff. As to the other 25%, the supply chains will recalibrate to absorb some of the tariffs, reroute exports to the US through other countries, and figure out alternative markets. At worst, the Indian economy will slow down by about a percentage point for a year or two. But it may also be the much-needed kick up the butt to double down on domestic manufacturing.

Instead, the more damaging problem for India from Trump tariffs is likely to be its impact on the foreign investment climate. At a time when the trend of decoupling from China is at its peak, multinational corporations are evaluating choices to diversify their supply chains. Given its large economy and potential for scale manufacturing, India would be among the frontrunners for most corporations looking to relocate from China. But the very high tariffs will undoubtedly be a significant dampener on the preference for India.

For example, if the uncertainty persists, would Apple go full hog (as it appears inclined now) with making India its alternative to China as the preferred manufacturing base? It is more likely that it’ll forego a share of its unreasonably high profits and reshore significant parts of the iPhone supply chain to the US and neighbouring countries like Mexico. Further, at higher tariffs, countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, Mexico, and Indonesia become more attractive for companies relocating out of China.

An even bigger threat for India will be if Trump turns his gaze on the services sector. One of the original grievances of the MAGA base is that of foreign migrants and services outsourcing taking away Americans’ jobs in the IT industry. India is especially vulnerable on this issue and to any punitive actions in these directions.

Already, Republican Congresswoman and Trump supporter, Marjorie Taylor Greene has called for ending H1B visas to Indians to punish India for buying Russian oil. The MAGA originals, led by Steve Bannon, have already made their opposition to H1B visas very clear, and they have also opposed US technology firms offshoring services to countries like India. In fact, this view may even have bipartisan consensus among populists on the right and the left. Given how far Trump has shown willingness to go with his protect American jobs agenda, it’s most likely that at some time during the next few months, there will be something that will trigger a backlash against not only H1B visas but the outsourcing of IT services sector jobs to India in the form of Global Capability Centres (GCCs).

Any actions on this front by Trump will have a strong adverse impact on India. India must work the backdoors quietly with the US Big Tech firms, whose interests would be hurt by these measures, to avoid these scenarios. Like Tim Cookand Jensen Huang, it must create the conditions for quiet lobbying by the technology firms to prevent any such eventuality. In the early days of the Trump 2.0 administration, a public dog-fight on this issue was staved off because influential voices on the elite corporate side in the US stepped in to counter the MAGA originalists. This issue can erupt anytime, and a Trump who’s antagonised with India may well flip to the other side this time.

In this backdrop, India would do well to adopt Deng Xiaoping’s famous aphorism that China follow the principle of “bide your time, hide your strength” (tāo guāng yǎng huì) during its growth phase. While always a prudent thing to do for a rising power, this approach assumes even greater relevance in times of Donald Trump and rising trade protectionism. National interests, especially when involving populist concerns, are best protected quietly. In any case, foreign policy is best conducted discreetly and away from the glare of media attention, much less the hyper-sensationalising modern social media.

Instead of being caught up excessively with speculations centering exclusively around ego slights, India would also do well to pay close attention to the purely transactional nature of Trump’s foreign policy actions.

For example, as David Woo has argued, there’s a compelling argument that the punitive tariff on India for importing Russian oil is part of the larger effort to force Russia to the negotiating table on Ukraine. Though Trump had prioritised the ending of “Biden’s war” in Ukraine, Putin’s intransigence had made the deal elusive. Woo argues that the EU may have agreed to the 15% trade deal also in return for the US pressuring Putin to end the war, and accordingly, in its aftermath, Trump shortened the deadline for Russia from 50 days to 10 days (August 8). Knowing that squeezing oil revenues is the “cheapest and easiest way to weaken Russia”, and that pressuring China was off the table, India (its Russian oil imports) may have become an easy soft target to pressure Russia into ending the war. India may well be collateral damage in Trump’s illusion of stitching together a grand bargain and claiming credit for ending the Ukraine war. Woo also says that given the certainty of a significant knock-on effect on global oil prices from India even looking to replace the 1.6-1.8 million barrels it imports from Russia, there’s a strong likelihood of a TACO round the corner.

The same transactional approach may be behind his sudden warming up to Pakistan. The trigger may well have been Iran, where Pakistan appears to have positioned itself as a partner to advance America’s interests. It has also offered the prospect of being a bitcoin mining hub, a source of rare earths, opening to US oil companies for oil exploration, and perhaps even being an intermediary between the US and China. All these, coupled with the support for a Nobel Peace Prize for Donald Trump and smart tactical positioning, appear to have swung Trump to strike a deal that lowered its tariffs from the interim rate of 29% to 19%.

The worrying thing for allies like India is the extent to which Trump is willing to take his transactionality approach in foreign policy. Despite being strategic allies, India and the US have had disagreements on one another’s relationships with third countries. Just as the US is displeased with India’s closeness to Russia, India has even greater reasons to be worried about America’s engagements with China and Pakistan. But both, including during Trump 1.0, have consciously agreed to live with these disagreements and avoid letting their serious differences come in the way of the deepening strategic relationship. As Evan Feigenbaum has said, Trump’s recent actions may have definitively destroyed that trust.

It’s a universal truth that with bullies, one must stand the ground or be bullied. Conceding to Trump’s demands and actions will certainly be seen as a sign of weakness and risks further entrenching the already existing belief in him that, in his games involving the big powers, India, being the softest target, can be compromised. This does not mean standing up to him loudly and aggressively through public posturing and tit-for-tat responses, as appears to be the strategy adopted by both Brazil and China, but being quietly firm in its actions and diplomatic communications. It should be supplemented with subtly delivered signals on policies and decisions on procurements and investments that are a reminder of the economic levers available to India.

The, by now, self-evident flippancy and whimsical nature of Trump’s policies should be a reminder to all those who thought that Trump would be favourable to India’s interests. A late 2024 poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations found that 84% of Indians believed Trump was beneficial for India, the highest percentage among 24 countries. This expectation was formed by narratives that had little evidence base.

In fact, even a cursory reading of the totality of his actions should have been proof enough that Trump has no ideology, and nobody can count Donald Trump as a friend. Trump’s America First and trade deficit focus, the transactional nature of his actions, and his preference to conduct foreign policy through Truth Social and media briefings must have been sufficient to point to the strong possibility of difficulties surfacing in the relationship. In conclusion, Trump is purely transactional, and it’s only one news story or ego bruise for Trump to reverse course from seeing a country as a friend to making it a villain.

Robert Zoellick, the former USTR and World Bank President, says it best;

“Trump is not fundamentally about policy. He’s about dealmaking and transactionalism and he has recognised that the United States has tremendous economic power and that tariffs are leverage and a way of showing dominance.”

Even worse, he does not mind the selective application of tariffs to certain countries on the same thing (punish Canada with 35% tariffs for moving to recognise Palestine, while ignoring France and UK; or punish India with 25% tariffs for purchasing Russian oil, while ignoring China’s greater purchases). Or, he may not be bound by any of his own deals and appears willing to tear them down if some new rationale or expediency emerges! The Tariff Man is the Transaction Man!

1 comment:

Sir, I feel this is one of your best posts, which is saying something.

Post a Comment