1. Profile of Wang Chuangfu, founder of BYD

Born in 1966 in the eastern province of Anhui, Wang is part of a generation of Chinese entrepreneurs who escaped poverty to join the nation’s newly minted billionaire class... Wang’s obsession with batteries led to a pivot to vehicles in the early 2000s. Cracking the five-minute charge this week builds on his pioneering “cell-to-body” technology — sandwiching a battery cell inside a vehicle’s structure... The company’s stock rally has also taken Wang’s personal net worth, according to Bloomberg data, to just shy of $30bn, making him one of China’s richest men. Despite that he remains a workaholic who lives humbly. His house is walking distance from BYD’s main factories and he dispatches lieutenants to public-facing events unless his attendance is absolutely necessary. Underlings have long described Wang as a restrained, highly detail-orientated micromanager. His approval was once sought for a business unit to distribute fruit to team members. But his passion for batteries has revealed a performative flare. To demonstrate to an investor just how safe his battery cells are, he has drunk battery electrolyte fluid. He has reused cells after trucks drove over them and frequently shows visitors batteries being penetrated by nails.

BYD plans to manufacture in India with a JV partner.

2. Interesting insights from a survey of over 30,000 GenZ professionals and 700 HR leaders.

Unstop, the community engagement and hiring platform for students and graduates, said that 83% of engineering school (E-school) graduates and 46% of business school (B-school) graduates remain without a job or internship offer in its report ‘Unstop Talent Report 2025’. A significant 51% of GenZ professionals seek multiple income streams through freelancing and side hustle, with the number rising to 59% among B-school students. The report also delves into the glaring gender pay gaps. Two in three female arts & science graduates earn below ₹6 LPA, while their male counterparts largely surpass this mark. However, B-schools and E-schools demonstrate pay parity, ensuring fair compensation irrespective of gender.

3. Borders and proximity is what matters on defence spending in Europe.

There is an inverse relationship between the two, with the well-protected south of Europe skimping, and the exposed north-east spending well above the Nato mark of 2 per cent of GDP. What compounds this problem are the respective populations. Portugal, one of the lowest spenders, has more people than all three Baltic states combined. Spain is bigger than Poland.

China has built more than 120,000 wind turbines, nearly a third of the world total, and 1.5 million acres of utility-scale solar.

For millennia, people thought differently about words, actions and liberty. Instead of valuing liberty of expression, their main preoccupation was to limit it. Because they were acutely aware of the power of words and the danger of lies, slanders and other kinds of harmful speech, the public policing of such things was a central feature of every premodern society across the globe. “Free” speech, by contrast, was an exceptional mode, which took different forms — divine prophecy, frank advice to a ruler, religious disputation or the exchange of ideas within the scholarly Republic of Letters. Only around 1700 did our modern notion of it, as a general right to speak out on matters of public concern, begin to emerge...In 1695, amid political and religious disagreements, the English parliament failed to renew a law mandating the pre-publication licensing of books. The result was an explosion of novel kinds of print, and a growing international fascination with “liberty of the press” as an engine of enlightenment. The two competing models of free speech that we’ve inherited were created in this new media world. The first approach contrasted press “liberty” (which was beneficial) with “licentiousness” (which was harmful) — responsible vs irresponsible speech, rights vs duties. That balancing attitude remains, globally, the norm... The alternative, absolutist model of free speech was invented in London in 1721 by two partisan journalists, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon. As I discovered, they were mainly writing to defend their own corrupt practices, and their theory was full of holes. Nonetheless, the slogans of their hit column, “Cato’s Letters”, which proclaimed that free speech was the foundation of all liberty and should never be curtailed, were soon taken up across the world, including by the rebel colonists of North America, who enshrined its clumsy formulations in their First Amendment — “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”. No ifs, buts or qualifications.In no other country have speech laws ever taken that absolutist form. The subsequent history of American attitudes is full of unappreciated ironies. Even before the First Amendment was ratified in 1791, Americans abandoned its approach in favour of the balancing model popularised by the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man. Until the 1910s the First Amendment remained a dead letter; it was only the radical, now forgotten arguments of US socialists and communists that subsequently resurrected it. Early theorists of free speech mainly conceived of it in terms of public opinion, assuming that liberty of expression would eventually lead to consensus about everything...But from the 1960s, as part of the cold war backlash against collectivist ideologies, interpretation of the First Amendment swung instead towards its current, libertarian outlook. This produced an American jurisprudence obsessed with clear and abstract rules — which was gradually achieved by ignoring libel, falsehood, civic harm, the responsibilities of the media and all the most difficult problems of how communication actually works in the world. Its simple, anti-governmental interpretation has also been increasingly hijacked to invalidate laws regulating businesses, restricting money in politics or otherwise attempting to uphold the common good. Legally, corporations are persons, and the First Amendment trumps everything.

The author makes an important distinction between free speech and its amplification.

It is a mistake, when grappling with freedom of expression, to focus too much on speakers. Especially in our age of 24/7 viral media, the critical issue is not speech per se but the responsibility for its amplification. It’s entirely reasonable to require the private media (whether printed, broadcast or online) through which most “public” speech is actually circulated and consumed to be transparent in their practices, and accountable to the society in which they operate. That means at a safe distance from direct governmental control, but more than just the fig leaf of “self-regulation”.

Zambia and Tanzania are negotiating with a consortium led by the state-owned China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation for a $1bn concession to rehabilitate and run the iconic... Tazara railway that links copper-rich, landlocked Zambia to Tanzania on Africa’s east coast... reviving the strategic export route to Beijing... Tazara showcases an attempt to use more equity investment by Chinese state companies after Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative was marred by defaults in borrower countries, including Zambia... Started in 1970, the Tazara railway was designed to help copper-rich Zambia access overseas markets after white-controlled neighbouring Rhodesia, today Zimbabwe, shut its borders in opposition to the country gaining independence from Britain...

Under Mao, Beijing forked out Rmb1bn in interest-free loans to build the Tazara, with thousands of Chinese labourers working alongside locals. At its peak, it ferried more than 1mn tonnes of copper, consumer goods and passengers annually. “The Tazara to this day is still the biggest Chinese aid project implemented in Africa,” said Tim Zajontz, a lecturer at the University of Freiburg. “It continues to be a symbol of the Chinese-African all-weather friendship, as many officials on both sides often refer to it”...A rival US-backed project is under way to upgrade the colonial-era Lobito Corridor and ferry Zambia’s resources westward through Angola instead. Agreed under former president Joe Biden through the US International Development Finance Corporation, Washington is lending $553mn to the railway in a model that brought in private investors such as Trafigura and Mota-Engil.

8. While the tech stocks and US stock markets appear to be in a bubble, there are historical precedents. The US has been the leader throughout most of the last century, except a brief interregnum when Japan took over.

Big Tech's 37.4% of the market capitalisation in 2025 pales before the 62.8% capitalisation of Railways in 1900.

Roughly half of Musk’s $314bn net worth is now tied to SpaceX — which was valued at $350bn in a recent private tender offer — while his 20 per cent stake in Tesla has dwindled to $100bn. Morgan Stanley estimates Starlink will generate $16.3bn in revenue this year, up 74 per cent from an estimated $9.3bn in 2024, with subscribers almost doubling to 7.8mn from 4.65mn, according to a January report. By comparison, SpaceX’s rocket launch business is forecast to make $5.8bn in 2025 revenue, up 20 per cent from $4.9bn last year... Starlink has said its more than 7,000 low-orbit satellites provide service to 118 countries and territories, with Niger the latest to be connected last week... It has won contracts with major airlines including state-backed carriers Qatar Airways and Air France, shipping groups including MSC and Maersk, and cruise operators Cunard and Carnival. About a quarter of the company’s revenues come from government contracts, however. According to US filings, SpaceX has already secured 39 different Starlink contracts across the US government worth around $3.5bn, including multiple military contracts with the Department of Defense.

10. Even as he takes the chainsaw to the US federal government, it emerges that Elon Musk's companies have received $38 bn in government contracts, loans, subsidies, and tax credits in the US over 20 years, with nearly two-thirds coming in the last five years.

“Not every entrepreneur at this scale has been this dependent on federal money — certainly not Nvidia, not Microsoft, nor Amazon, nor Meta,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, professor at the Yale School of Management, who noted that much of the funding has come during Democratic administrations. “With DOGE, there does seem to be a paradox there. He has been a big beneficiary of national industrial policy, especially Democrat industrial policy, through government funding.” Government funding also provided key early infusions to Musk’s ventures. NASA and the Defense Department nurtured SpaceX in its earliest years with contracts that helped it build infrastructure, while the agency tolerated the company’s failure to meet required milestones on time, according to congressional investigators. The $465 million Energy Department loan, which arrived in 2010, helped fuel Tesla’s meteoric rise: With that money, the company engineered and assembled its luxury electric sedan — the Model S — and bought a factory in Fremont, California, according to the agency. Tesla went public six months later... Since its 2003 Silicon Valley founding, Tesla has benefited from billions in rebates and tax credits from California. The state’s governor, Gavin Newsom (D), has claimed that “there was no Tesla without California’s regulatory bodies, and regulation.”... About a third of Tesla’s $35 billion in profits since 2014 has come from selling federal and state regulatory credits to other automakers... Tesla is the largest seller of these credits to automakers that don’t meet the standards and want to avoid paying a fine.And that of Space X11. Big Tech and job creation graphic of the day, Nvidia edition. (HT: Adam Tooze).

The number of duty-free shipments to the United States has risen more than tenfold since 2016, to four million parcels per day last year. Similar shipments to the European Union have climbed even faster, reaching 12 million parcels a day last year. Duty-free shipments to developing countries like Thailand and South Africa have also surged… Last summer, South Africa imposed 45 percent tariffs on even the smallest imports of clothing. Thailand ended its exemption of low-value imported parcels from sales taxes, although it continues to allow tariff-free entry of parcels up to 1,500 Thai baht ($44). And the European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union, proposed this month to end the 27-nation bloc’s duty-free treatment of packages worth up to 150 euros ($156)…

Guangzhou has emerged as the global hub of de minimis shipments… Shein and Temu, competing Chinese e-commerce giants that together hold at least a third of the de minimis industry, coordinate much of their supply chains from large offices in Guangzhou… Yiwu, a city 600 miles northeast of Guangzhou with a vast wholesale market, has become another hub. It coordinates de minimis exports of toys, hats and other small items from towns scattered across the Yangtze River delta.

13. Mihir Sharma hits the nail on its head in his diagnosis of the ongoing trade wars

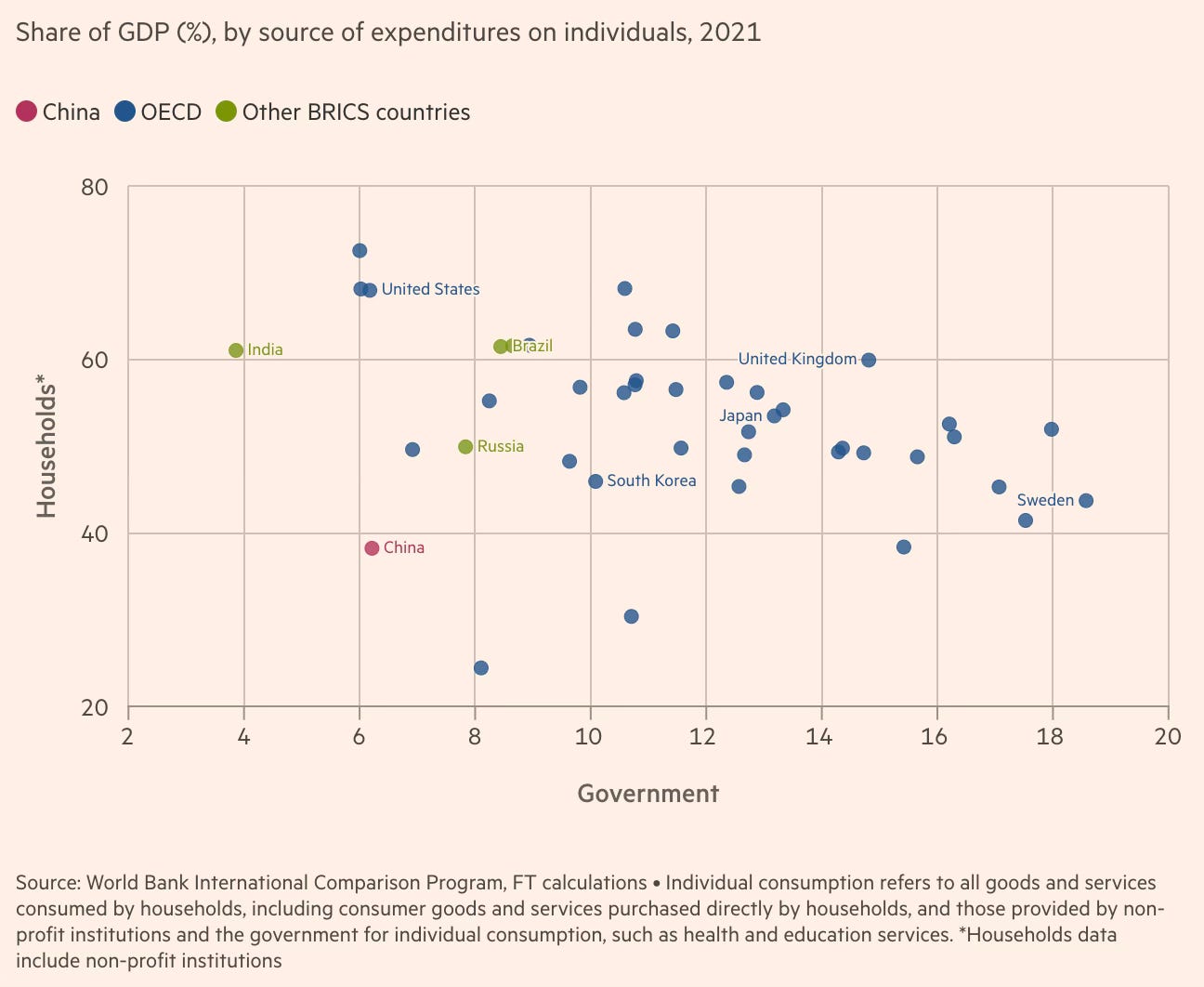

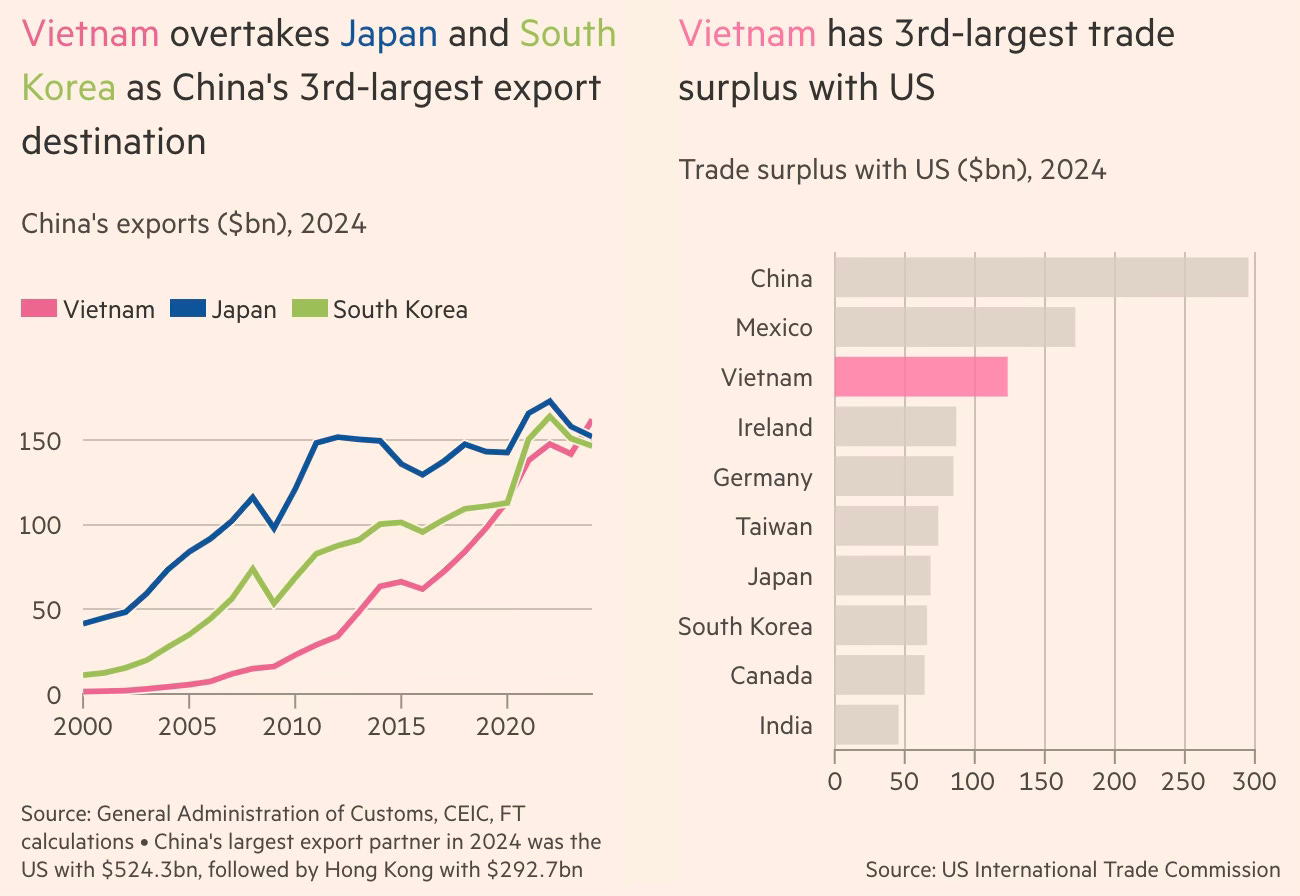

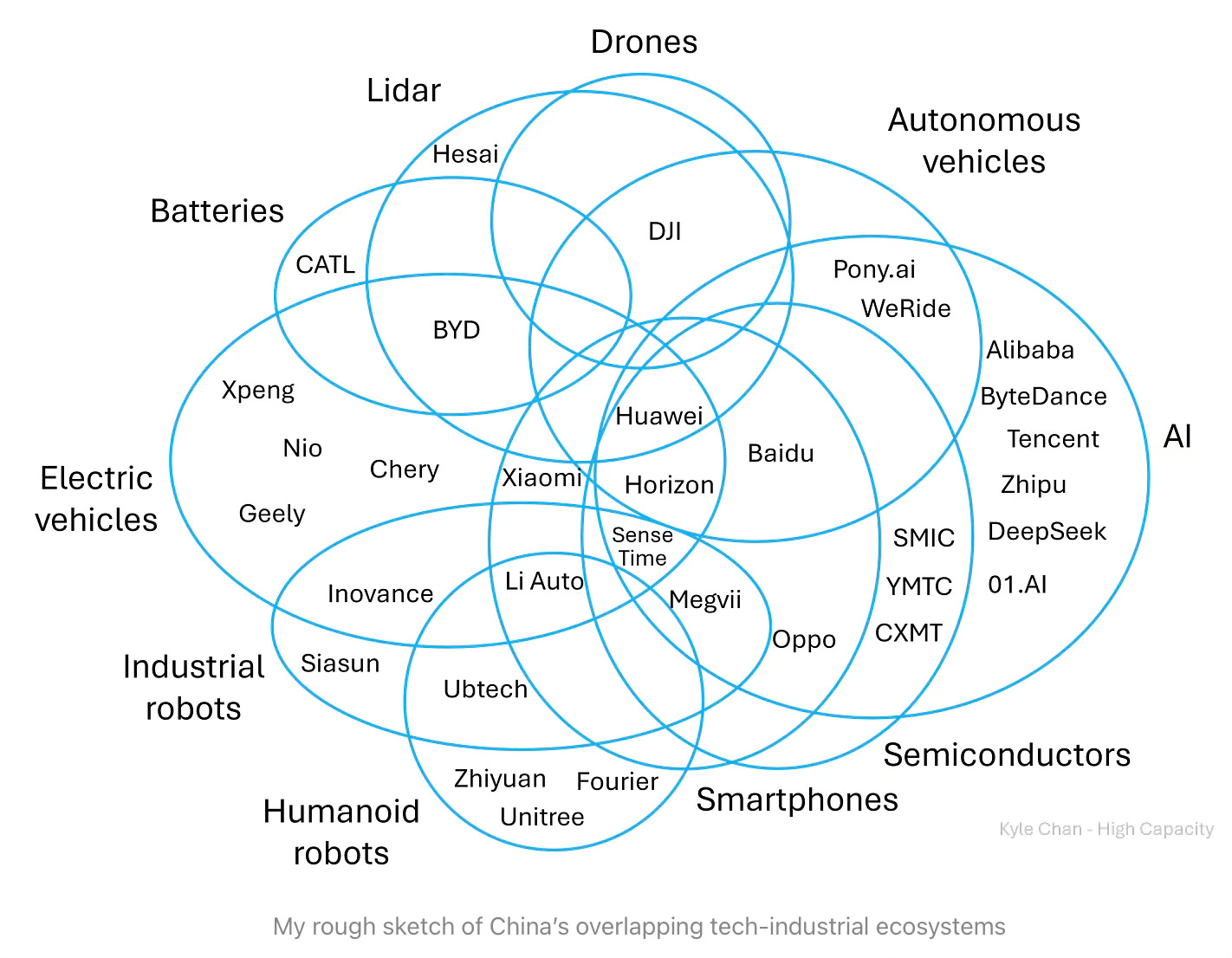

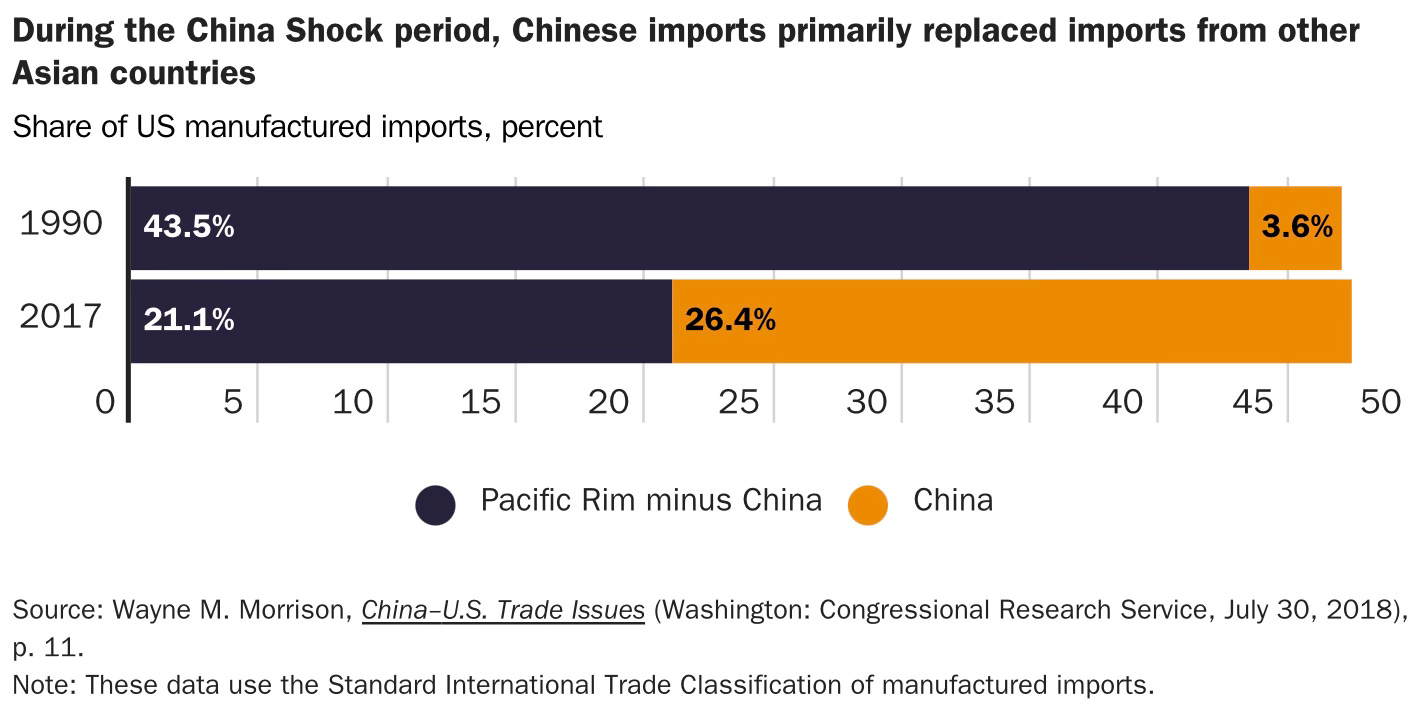

The fundamental flaw at the heart of how international trade in the era of the World Trade Organization (WTO) functions is the polite assumption that all economies are similarly structured. In other words, that costs, subsidies, and protections are transparent. Unfortunately, the biggest trading power in the world does not meet these criteria. If the People’s Republic of China violates this assumption, then the entire trading system is built on a lie. It is to this baseline problem that US actions, and those of others from the European Union to India, are responding. China’s accession to the WTO was premised on the assumption that its economy was, or eventually would be, comparable to the market economies that designed the system. The fact that it was not then; nor has it tried hard enough since to become one. As a consequence, it has built up imbalances domestically — and, thanks to its sheer size, those imbalances have expanded and mutated till they cover the entire world...Hidden subsidies to power, land, and capital mean that competing with Chinese manufacturing has become very difficult for more transparently-run economies. By some estimates, China has the lowest average electricity price for industrial users among major economies. It is about 60 per cent of the equivalent in India, and about a quarter that of Germany’s. Meanwhile, it has increased and is still increasing the use of targeted tax subsidies in export-oriented sectors such as electric cars, batteries, and solar panels. There is no recourse within the WTO system for China’s trading partners if they want to correct this issue. It is not entirely surprising that both parties in the US have lost faith in WTO dispute settlement.

14. Africa's India rice dependency

Africa is typically a large market for broken rice — accounting for more than 80 per cent of India’s exports over 2018-20, according to data from the International Food Policy Research Institute. In 2022, Indian rice accounted for more than 60 per cent of rice imports for 17 African countries and more than 80 per cent in nine, including Somalia.

15. Trump bump has raised the flagging prospects of political leaders in many allied countries.

Over the next few months, he will have to find a way to balance the interests of both the fiscal hawks and billionaire allies, who want to radically downsize the federal government, and his working-class Maga base, which has become heavily reliant on government support... a growing section of voters has come to rely on government transfers, the result of an ageing society and rising inequality. These include Medicaid for poorer families and Medicare and Social Security for retirees. In 2000, according to the Economic Innovation Group, a think-tank, just 10.4 per cent of counties in the US derived a quarter or more of their total personal income from transfers. But by 2022, that had risen to 53 per cent of counties in the US. Many of those counties are in the sort of rural areas where Trump is hugely popular.

“As much as Republicans like to rail against big government, [their voters are] often its biggest beneficiaries,” says John Mark Hansen, professor of political science at the University of Chicago. Or as Steve Bannon, one of the architects of Trump’s initial rise to power, put it in a recent podcast: “Medicaid’s going to be a complicated one . . . a lot of Maga’s on Medicaid.”... Income from government transfers was the fastest-growing major component of Americans’ personal income, according to the EIG report last year. It said they made up 18 per cent of all personal income in the US in 2022 — a total of $3.8tn — with the share more than doubling since 1970. Transfers, which include state pensions and state health insurance, as well as veterans’ benefits, food stamps, unemployment insurance and other benefits, were now the third largest source of Americans’ personal income, after income from work and investments, EIG said. The main driver of this trend, EIG said, was the ageing of the US population. Because the largest transfer programmes — Social Security and Medicare — are aimed at people of retirement age, transfer payments expand as the elderly population grows...

The trend is not confined to a few poor pockets of the country. The report says that “most US counties depend on a level of government transfer income that was once reserved only for the most distressed places”. It said the transfer share runs highest in parts of the country that are “rural, old and poor”. Some of these, Appalachia and the rural South, are firmly Republican... A report by the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University in January found that there are 15 states where at least one-fifth or more of non-elderly adults in small towns and rural areas are covered by Medicaid. Of these, eight voted for Trump in November.