Deregulation is making a comeback. The return of Donald Trump as the President of the US looks likely to usher in a period of unprecedented deregulation in the US. Unlike the first term, the composition of his Cabinet appointments and their clear political mandate means that the government bureaucracy may not be much of a bulwark against deregulation. The Department of Government Efficiency has been established to shrink the government and deregulate.

Before Trump, Javier Milei in Argentina has been loudly taking the chainsaw to regulations. New Zealand has set up a Ministry for Regulation, Vietnam plans to abolish a quarter of government agencies, and the French government promises de-bureaucratisation. In the UK, the Labour government established a Regulatory Innovation Office to cut regulation to unlock growth.

In India, there are calls for a second wave of deregulation to follow up on the economic liberalisation of the early nineties. In her recent Union Budget Speech, India’s Finance Minister announced several measures that pointed to deregulation becoming a priority for the government.

In the last ten years in several aspects, including financial and non-financial, our Government has demonstrated a steadfast commitment to ‘Ease of Doing Business’. We are determined to ensure that our regulations must keep up with technological innovations and global policy developments. A light-touch regulatory framework based on principles and trust will unleash productivity and employment. Through this framework, we will update regulations that were made under old laws… A High-Level Committee for Regulatory Reforms will be set up for a review of all non-financial sector regulations, certifications, licenses, and permissions… The objective is to strengthen trust-based economic governance and take transformational measures to enhance ‘ease of doing business’, especially in matters of inspections and compliances. States will be encouraged to join in this endeavour… An Investment Friendliness Index of States will be launched in 2025 to further the spirit of competitive cooperative federalism… In the Jan Vishwas Act 2023, more than 180 legal provisions were decriminalized. Our Government will now bring up the Jan Vishwas Bill 2.0 to decriminalize more than 100 provisions in various laws.

Recently, The Economist had a leader on the subject. It points to the pervasive spread of regulation.

Americans spend a total of 12bn hours a year complying with federal rules, including those on marketing and selling honey, and following standards on the flammability of children’s pyjamas… In the past five years the European Parliament has enacted more than twice as many laws as America. Businesses are required to make painstaking sustainability disclosures, filling in more than a thousand fields on an online form—an undertaking that is estimated to cost a typical firm in Denmark €300,000 ($310,000) every year. In Britain, well-meaning rules protecting bats, newts and rare fungi combine to obstruct, delay and raise the cost of new infrastructure.

And more here

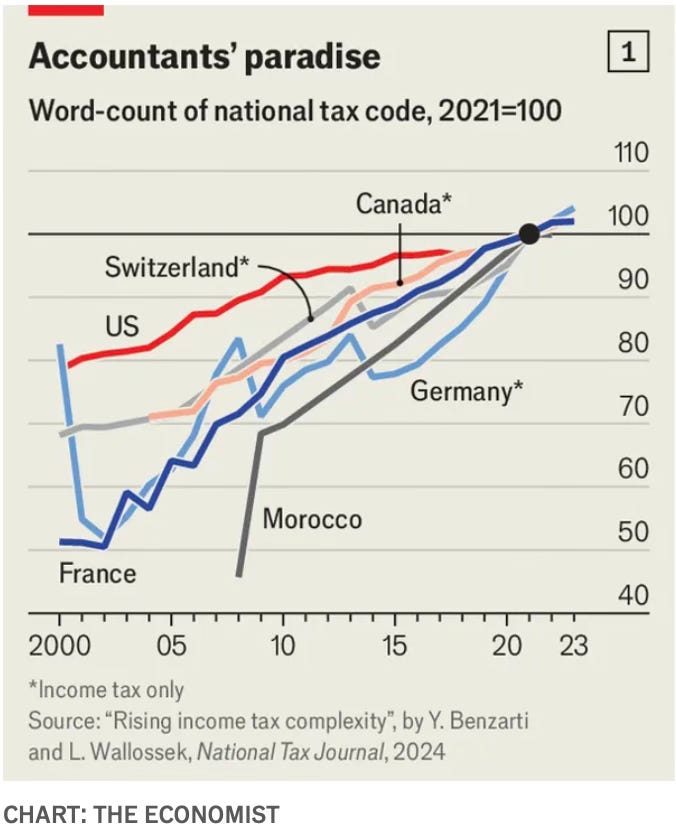

According to the Regulatory Studies Centre at George Washington University, federal regulations in America now exceed 180,000 pages, up from 20,000 in the early 1960s. Official figures suggest that the federal government imposes 12bn hours of paperwork on Americans each year, or about 35 hours per person, up from 27 hours per person in 2001. The complete text of all German laws has 60% more words than in the mid-1990s. Over the past 20 years tax codes from Canada to Morocco have swollen.

The Economist has examples of regulations whose cumulative costs are significant

Take estimates of the cost to American banks of filing the “currency transaction report” required by law every time someone withdraws or deposits $10,000 or more. The government says this costs about $3.50 a report; banks $10-80… Hundreds of thousands of firms in California must put up signs stating that their premises “contain chemicals known to the state of California to cause cancer”. Other firms must post signs in bathrooms telling staff to wash their hands. Hotels must have signs next to pools urging people with “active diarrhoea” not to bathe. In France a house cannot be sold unless a notary reads the contract aloud in the presence of the buyer and seller. Each of these bureaucratic follies is typically only a minor expense and inconvenience. Cumulatively, however, they stifle economic activity, like Gulliver tied down by lots of pieces of string… Across the rich world the share of employment in jobs with mandatory qualifications is rising. Bakers, hairdressers and painters often have to obtain licences before being allowed to work.

In this context, I have a few observations (both about regulatory thickening and deregulation):

1. Deregulation is back with a bang. Much of the revival of faith in deregulation owes to an unsaid realisation that all the conventional drivers of economic growth are struggling for one reason or another. In searching for economic growth drivers, governments have been led to believe that deregulation may be the answer, perhaps even a low-hanging fruit. Like privatisation, outsourcing, digitisation, cash transfers, and so on, deregulation is the latest in a series of trends that become the fad in efforts to foster growth and development.

2. I can think of two major well-intentioned but unintended contributors to the regulatory thicket - the desire to prevent manipulation of any new intervention or policy and to maximise objectives or goals.

The former arises from the bureaucratic instinct to control for abuses (in services like building permissions and statutory certificates), leakages (in taxation), safety (in food regulations), security (in telecom licenses), consumer protection (generally across private services), etc. There’s a trade-off between the benefits from controlling for these factors and their associated costs.

There’s also a self-fulfilling dynamic to such regulation. Periodically, there emerges some news of egregious manipulation by the customers (citizens, corporations, organisations, etc.), which generates a public backlash. Governments respond with more regulation to prevent such manipulation. This becomes a self-reinforcing spiral of regulatory thickening.

The latter is more political and about virtue signalling. The NYT commentator Ezra Klein has described this as “everything bagel liberalism”, where government adds laudable goals (on diversity, inclusion, and equality) to an intervention aimed at achieving some high-level objective that, in turn, ends up adding obstacles, delays, and expenses. Regulations on trade, industrial, procurement, labour, environmental, and building permissions tend to suffer from this.

3. Deregulation can run the risk of being reduced to a pro forma exercise of tweaking rules and procedures to meet some notional requirements. The Ease of Doing Business (EoDB) rankings are a good example of a reform where form trumped substance. Over time, state governments in India have sought to improve their rankings by notional tweaking of the laws and rules to meet the ranking requirement without substantively changing much on the real business environment. The system got ensnared in the ranking game.

This highlights the importance of also viewing deregulation in terms of changing cultures and mindsets. The EoDB is about embracing a collective mindset that eschews harassment and adopts an attitude of facilitation towards businesses, one that goes beyond mere procedural tweaks

4. Developing countries must guard against isomorphic mimicry of regulations imposed by developed countries in emerging areas like data safety and privacy, artificial intelligence, climate change, etc. It’s tempting to adopt state-of-the-art policies and laws from advanced countries to address emerging issues in these areas. But such regulations invariably add to costs and act as a drag on economic growth.

In the Indian context, the effort to formalise the economy in quick time has the unintended consequence of adding regulation and their associated costs to those activities.

5. Regulations emerge from the collective instincts and incentives facing bureaucracies. Their elimination (or meaningful deregulation) is unlikely to emerge from within bureaucracies unless the deregulation agenda is politically driven.

Deregulation must, therefore, be led and tightly monitored politically. Any deregulation mandate left to the bureaucracy and executed largely by itself is unlikely to be effective. Similarly, any deregulation mandate recklessly executed, as by the DOGE in the US, is certain to go down the route of cronyism, corruption, and abuse, besides irreversible weakening of state capability.

6. A few principles come to mind while considering deregulation. Deregulate where costs far outweigh the benefits; deregulate where the state capability to enforce effectively is negligible; deregulate where violation is the norm; where multiple objectives are being sought to be achieved, deregulate on the secondary objectives; deregulate where there are non-regulatory solutions to achieve the objective; if there are significant quantifiable costs from the regulation, allow for internalisation of those costs, etc.

A good starting point for meaningful deregulation would be to formulate a set of principles that should underpin any deregulation. This can be in the form of a checklist to scrutinise every provision in the regulation. It may be prudent to start with a few regulation-heavy departments that are proximate to private sector investments, identify those regulations that are first-order relevant, and then list out those provisions in each that can be construed as excessive regulation. The shortlist must be scrutinised against the checklist of principles and deliberated before a decision is taken.

No comments:

Post a Comment