The UK water utilities are a great case study on the problems of privatising public facilities. I have blogged on multiple occasions (here, here, here, and here), and this post updates the numbers based on a recent NYT article.

It has the latest balance sheet of water utilities privatisation in the UK

When the British government, under Margaret Thatcher, privatized water utilities, it went further than many other countries had. The water and sewage assets were transferred to companies with limited liability and cleared of debt. Shares were floated on the stock exchange, but most of the companies are now privately held, a relatively rare ownership model, though some countries or cities have contracts with private companies for the management of the water systems…

Across England and Wales, insufficient investment in the sewage infrastructure and the water supply has led to a crisis that has been brewing for years. Now, more people are putting the blame on the ownership of the water utilities, which are regional monopolies, predominantly owned by multinational conglomerates and asset managers, including sovereign wealth funds and pension funds. Critics argue that shareholders in the water companies have received billions of pounds in dividends since privatization but failed to put enough money back into the water system while piling up debt…

Thames Water, which has debt of about £15 billion, or $20 billion, said it would run out of cash by May if it was unable to raise more equity. Its shareholders, who own the company through Kemble Water Holdings, include a Canadian pension fund, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund and a British pension plan for university staff, and they have been reluctant to inject fresh cash amid clashes with regulators over how much to raise customers’ bills... The average utility bill in England and Wales is £441 a year, higher than some of their European neighbors, like France, but lower than others, such as Norway. Ofwat has proposed increasing consumers’ bills by more than a fifth on average over the next five years.

And the public reaction to this state of affairs has swung towards nationalisation.

The 10 water utilities in England and Wales, which were privatized in 1989 during a wave of deregulation and free-market liberalization, have become a target of public ire over polluted waterways and rising household bills. The number of people getting sick from the water is growing… In June, the Henley Town Council called for the nationalization of Thames Water, which serves about 16 million people, saying the company’s track record has been “beyond concerning.”.. More than 80 percent of Britons said water companies should be run in the public sector, according to a poll in July. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, the water companies are owned by their governments. In 2001, one of Wales’s water companies became a nonprofit organization.

The market is a good mechanism for efficiently allocating general goods and services. But when the goods and services are essentials for human survival and especially when monopolists provide them, the market has been consistently found to fail the allocation test. This is why utilities are tightly regulated and outright privatisation is rare in sectors like water, sewerage, mass transit, and electricity distribution. In fact, the water and sewerage sector is publicly owned in most of the world. There’s a comparator in the UK itself

The Scottish system has remained under public ownership and Scottish Water has invested nearly 35% more per household in the system since 2002 than counterparts south of the border, while it charges 14% less for water. It is reported that the highest paid director of Scottish Water took home less than £400 000 in pay and benefits in 2021—a fraction of what his English counterparts receive.

The UK water utilities are also a good case study on foreign investments in infrastructure sectors like water.

Famous investors in Thames Water included Australian Macquarie Capital Funds, until 2017 when they sold their share. Estimates at the time said the fund made between 15.5-19% in annual rate of returns, however, it also faced criminal fines of up to £20m in 2017 for leakages affecting the Thames. In September 2021 Macquarie re-entered the UK private water infrastructure market by investing £1.1bn in equity into Southwestern Water group committing to delivering reliable services and protecting and improving health of rivers and sea… Other well-known financial service companies include Blackrock, Lazard and Vanguard (Severn Trent, United Utilities and South West Water), Germany’s Deutsche Asset Management an US based Corsair Capital (Yorkshire Water). JP Morgan Asset Management owns 40% in Southern Water, and Australian Colonial First State Global Asset Management owns stakes in Anglian Water, Severn Trent, United Utilities and South West Water. Apart from these companies there are numerous other foreign investors from the Arab Emirates, Kuwait, China and Australia (Thames Water), a Malaysian company (Wessex Water), and Cheung Kong Group (Northumbrian Water), an in the Cayman Islands registered fund associated with Hong Kong’s richest person, involved.

The role and influence of foreign investors can be understood best when looking at the Thames Water external shareholders. Canada’s largest shareholder pension fund, Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), holds over 30% in the water and sewage systems company. The fund had net assets of $129bn at the end of 2023 and invested in Thames Water in 2017. The investment was made using several investment vehicles based in different locations, such as among others Singapore. Close to 10% in the company is held by Infinity Investments SA, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority who invested in 2011. The fund also has done an $800m investment into Statoil, a Norwegian natural gas transport company. In 2012, China Investment Corporation, one of the biggest sovereign wealth funds in the world has acquired a 9% share in Thames Water. Further foreign institutional investments include Queensland Investment Corporation, a government owned Australian investment firm (5.3%), and Stichting Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn, the second largest pension fund in the Netherlands… more than 70% of the privatised water industry in the UK is owned by foreign investment firms, private equity, pension funds and, in some cases, businesses based in tax havens, which raises concerns about the public utilities companies acting in the interest of shareholders rather than general population.

While foreign investments, in general, are not bad, as I shall discuss later, the nature of those investors might be a problem in essential public utilities. This is especially since their interests are unlikely to be aligned with the sustainability of the business and would be seeking to maximise their returns.

Apart from the general consumer welfare decreasing dynamics of monopoly markets, some important reasons for the market failure are the propensity of utility operators to skimp on investments and maximise returns. All these get amplified with private equity ownership, besides engendering other perverse trends like asset stripping by using leverage to pay dividends. Further, their relatively short investment horizons mean that their primary objective as owners is not to build enduring companies but to maximise the returns during their investment tenures and then pass the parcel to the next investors.

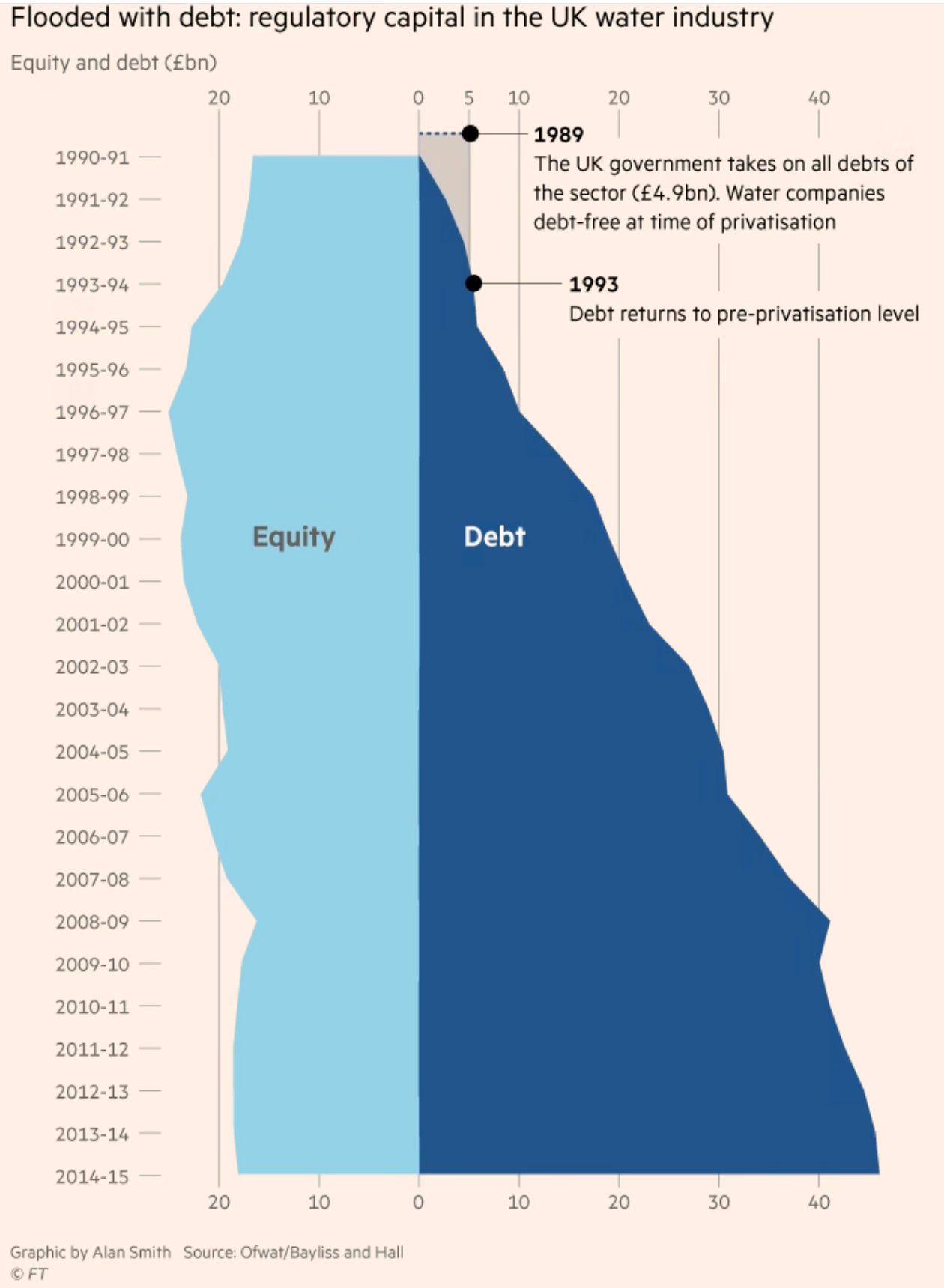

Consider the accounts of the water utilities. When the 16 water companies were privatised, the government wrote off all their debts of £4.9 bn and injected a green dowry of £1.5 bn to meet investment requirements. Since being handed over debt-free and till March 2023, they assumed £64 bn in debt, paid out £78 bn in dividends, and invested £190 bn.

In other words, in the 32 years since privatisation, the owners of the UK water companies took out or created obligations to the tune of £142 bn while investing only £190bn. Alternatively, for every pound invested from internal accruals, 62 pence was returned to owners, or nearly two-fifth of internal accurals was paid out as dividends.

A study in 2018 by Karol Yearwood of Greenwich University has this picture of Thames Water.

The company is now owned by a consortium of Private Equity and financial investors, having previously been in the hands of the infamous Macquarie Group since 2006. Shockingly, Macquarie borrowed more than £2.8bn to finance purchase, and later supposedly repaid £2bn of the debt through new loans raised by Thames Water through a subsidiary in Cayman Islands, effectively transferring the purchase costs to customers. Furthermore, in those 10 years, debt increased 2.3x times (from £4bn to £10bn), dividends averaged 270m per year, yet between 2011 and 2015 they paid no tax.

This article examines the Thames Water case in detail.

There are two defining graphics about how the UK water privatisation went wrong. The first shows how the utilities kept piling up debts even as their equity base remained the same (or even depleted).

The second shows that even as they were accumulating all the debt, the private companies were generating sufficient cash to meet their investment needs without taking on debt. In fact, they could have paid out an average of £1.5bn in annual dividends without taking any debt at all. Instead they raised debt and paid out more, thereby causing the current debt pile. It’s no coincidence that £1.5bn of customers’ money is spent yearly by paying interest on these loans.

The two graphs beg the question as to what was Ofwat doing all along. The trends were hard to miss. But Ofwat choose not to act. It is hard not to feel that Ofwat’s monitoring systems failed abjectly in raising red flags to rein in such practices. British water privatisation is as much a story of regulatory capture as it is of the avariciousness of private capital.

Ofwat’s role in the general failure of supervision and regulation has been a matter of debate for some time now. The British government has just constituted a commission to carry out a “root and branch” assessment of Ofwat and consider all options for the regulation of the industry. The Environment Secretary has blamed the regulator and lack of proper oversight for the failure of the water sector. The Commission, headed by former BoE Deputy Governor Jon Cunliffe, will “will look at strategic planning, protecting consumer interests, and how to come up with rules that hold companies to account without putting off potential investors.”

Ofwat is undertaking its latest five-year price reviews for the water utilities, on price determination for the period till 2030. The industry sought a 29% increase and got an interim direction for a 19% rise.

The graphs also draw attention to the point that I have repeatedly made in this blog on the importance of the nature of investors in regulated sectors like utilities. These are low but stable return sectors, appropriate for investors satisfied with low returns but seeking to diversify their returns.

It’s difficult to believe that private equity firms meet this requirement. PE firms are not known for their commitment to stakeholder responsibilities and for building enduring companies. They have a single-minded focus on maximising returns, which leads them into questionable practices like asset-stripping and loading up their portfolio companies with excessive debt. Their emerging track record across sectors point to a consistent practice of pass-the-parcel after squeezing out all possible returns from their investees. Monopoly public utilities like water and sewerage cannot be left exposed to such practices.

Instead of targeting specific categories of investors like PE or foreign funds in general, it may be useful for policy makers to put in place conditions that align the incentives of investors and also safeguards against asset stripping by private investors in regulated infrastructure sectors. This is an important requirement given the pass-the-parcel nature of dispersed private ownership associated with those like the kind of investors in UK water utilities.

The objective should be to ensure that investors be held accountable for the life-cycle of the infrastructure asset by mandating certain fiduciary responsibilities during their ownership of the asset. On the positive side, there should be adherence to clear investment responsibilities, service level standards, and maintenance of asset quality levels. On the negative side, there should be debt-equity ratio ceilings, caps on returns, and close watch on the finances of the asset holding company.

It’s also for this reason that private participation in public infrastructure like utilities, roads, mass transit etc., should be confined to simple concession contracts of services with tight caps on returns, including all kinds of payouts. It should be made explicit that the investors in such investments are fiduciaries and their value proposition is only stability of returns and not high returns.

No comments:

Post a Comment