I have blogged earlier on Guyana’s windfall from oil discoveries off its coast and how it conflicts with the climate change debate. This post will examine how it has perpetuated the age-old practice of large corporations entering into unfair exploitative contracts with resource-rich developing countries.

Guyana, one of the smallest South American countries and one without any hydrocarbon industry, has made one of the largest off-shore oil reserve discoveries in history. ExxonMobil, Hess, and Cnooc (a Chinese group), have discovered about 11 billion barrels of oil in Stabroek Block, about 120 miles off its coast, and have sanctioned investments of over $55 bn to extract just under half those reserves. Guyana’s economy grew by 33% in real terms last year and IMF predicts a similar rate this year too.

Such discoveries raise a standard set of concerns - reservoir boundary disputes with Venezuela, resource curse, corruption and exploitation by the oil companies (even the IMF agrees that the production sharing agreement signed by the government in 2016 is unduly generous to the oil companies) etc. In addition, there are now loud concerns by climate change activists who deem this discovery a “climate bomb”.

The resource curse has neighbourly precedents

Mobil, which Exxon later acquired, discovered oil off Equatorial Guinea in 1995; the three-decade boom that followed enriched the central African country’s ruling family but most of its population remained mired in poverty. Decades of oil production in Guyana’s western neighbour, Venezuela, gave way to economic mismanagement, corruption and authoritarianism. The country’s socialist leader, Nicolás Maduro, is reviving a historic claim to a Guyanese province that includes part of Stabroek.

The issue of exploitative contracting is never far away when three things come together - natural resource extraction, developing countries, and western mining corporations. Consider this from Guyana.

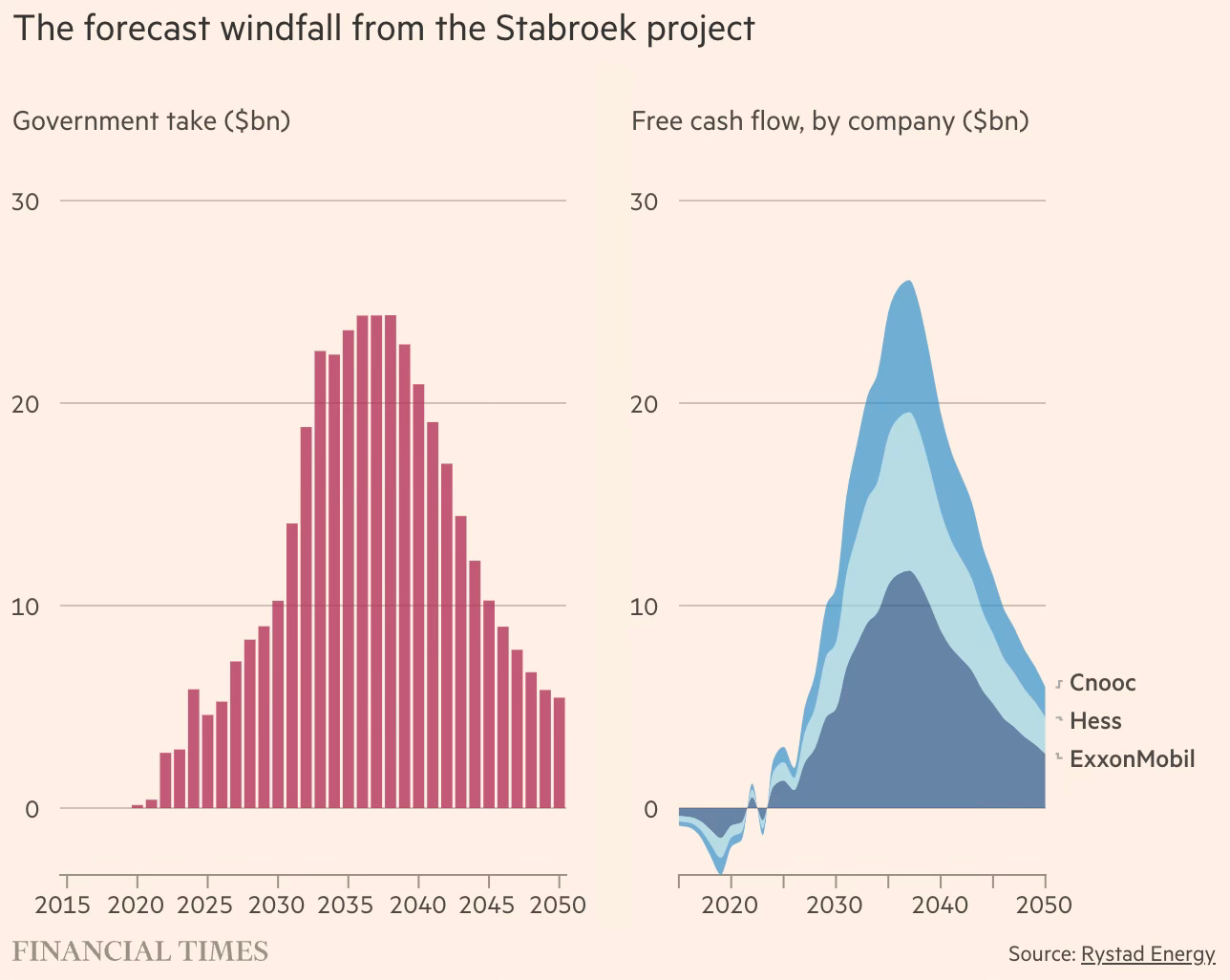

Consultants at Wood Mackenzie forecast Exxon and its partners will generate $135bn in profits between 2024 and 2040. Guyana will receive $150bn over the same period, a staggering amount for a country that had a national budget of $3.75bn last year. The consortium can collect up to three-quarters of revenue from the project until its costs are recouped. The remainder is split 50:50 with the government which also takes a 2 per cent royalty on production from the field — below the level in most offshore oil projects. It has also agreed to pay the companies’ income and corporation taxes from its share of the profits. The agreement is so lucrative that in March it sparked a corporate battle between Exxon and US rival Chevron, which wants to buy Hess in a $53bn deal. Exxon argues it has first refusal over any sale of Hess’s stake in the Guyana find and has initiated an arbitration process that could torpedo the Chevron deal.

The unfair nature of the contract is acknowledged by the Guyanese President himself

President Ifaan Ali acknowledges the deal is “skewed in favour” of Exxon but has not pursued a renegotiation. “The size of Exxon, in terms of the economy, tells you that you just couldn’t change the contract,” he tells the Financial Times. “It would have legal implications and the entire sector would have been held up.” Any new deals with oil companies would not be so “lopsided”, Ali says

I’m struck by the hypocrisy underlying this:

Critics say the production sharing agreement signed by the previous government in 2016 is unduly generous to the companies, a view shared by the IMF. There are also concerns Exxon is too close to the current administration, led by President Irfaan Ali, and riding roughshod over environmental laws… the government must negotiate with a corporation whose cash flow last year was more than three times Guyana’s GDP and which has huge experience of thrashing out complex contracts… More recently, US authorities imposed sanctions on a senior Guyanese official and several prominent businessmen allegedly involved in a $50mn tax scam in the gold sector. Mae Thomas, permanent secretary of Guyana’s Ministry for Labour, provided benefits to Nazar and Azruddin Mohamed in exchange for cash and gifts, according to the US Treasury.

Why didn’t the WB or IMF engage with Guyana and Exxon use its country leverage (over Guyana) and its ESG credential signalling (for Exxon) to support the country in negotiating fair contractual terms? Why doesn’t these institutions have a model production sharing contract that can be used as the template for countries as they negotiate with large multinational corporations? Why isn’t there a model code of conduct principles that serve as a moral suasion for western and other corporations engaging with countries on resource extraction?

After all, in value for money terms, supporting Guyana with technical assistance to negotiate a fair contract would be among the greatest investment the MDBs would have ever made. Instead of analysing, lamenting and blaming developing country governments of corruption in such contracts, IMF missed a great opportunity to demonstrate intent and illustrate with example. It could have engaged with both sides and helped seal the long-term future of the country by helping structure a fairer contract.

Why didn’t the US, which imposed sanctions to force out President David Granger in 2020 when he refused to stand down after losing elections, intervene and force Exxon to be more fair in the contract? Why does the US apply different standards to assess exploitative and abusive practices by its Corporations and nationals of developing countries? What moral right does the US and western opinion makers have when they question Chinese companies for exploitative resource contracting and lending when their own corporations are doing much the same or worse and have been doing so for so long and they do little to address it?

Why does Exxon itself not realise that any such unfair contract will be a lightning rod for opposition protests in a democracy (and the opposition has made this the main electoral issue in the 2025 elections)? Why does it not realise that such one-sided contracts invariably create the conditions for expropriation and other extreme reactions, not to mention the serious loss of credibility and domestic goodwill? Finally, where has all Exxonmobil’s ESG virtue signalling disappeared? If only corporations actually walked the talk with their ESG commitments when it came down to a trade-off involving the bottom-lines!

The takeaway from Guyana is that more things change, the more they remain the same!

No comments:

Post a Comment