Some thoughts about inflation in developed markets.

Here is some news about UK inflation prospects,

But with Europe’s gas crisis escalating in August, Citi predicted on Monday that inflation would reach 18.6 per cent in January. Continental European gas prices are more than 14 times their average of the past decade. The benchmark European gas price rallied almost 10 per cent on Monday to €278 per megawatt hour ($81 per million British thermal units), the highest closing price on record and taking the rise over August to 45 per cent. Examining the wholesale figures, Citi predicted that the UK’s retail energy price cap — which limits how much households pay for heating and electricity — would be raised to £4,567 in January and then £5,816 in April, compared with the current level of £1,971 a year. It added that the shifts would lead to inflation “entering the stratosphere”. The bank’s projected rate would be higher than the peak of inflation after the second Opec oil shock of 1979 when CPI reached 17.8 per cent, according to estimates from the Office for National Statistics.

An how sharply rising energy prices are feeding into this inflation

Natural gas, which is used to generate electricity and heat, now costs about 10 times more than it did a year ago. Electricity prices, tied to the price of gas, are also several times higher than what used to be considered normal... In Britain, the wholesale price of a megawatt-hour of electricity (enough to supply about 2,000 homes for an hour) hit a record daily average of about 500 pounds, or $590, early this week, roughly five times the level of last August.

Driving the prices is a fear that Europe will run out of gas this winter. Russia has slashed gas flows to Germany and other countries... Nord Stream 1, a key conduit of fuel to Germany, has been flowing at only 20 percent of capacity. These cutbacks are forcing gas providers to buy gas on the spot market at higher and volatile prices than under longer-term Gazprom contracts. In many countries, gas and electric power prices are closely intertwined, a relationship that has added to Europe’s woes. Although there are several ways to generate electricity — such as coal, nuclear, hydroelectric, wind and solar — the price of natural gas is hugely influential in setting electricity prices because gas-burning generators are most often paid to come into service when a power grid like Britain’s needs more electricity... Chris Matson of LCP estimated that in 2021 Britain’s power prices were determined by gas more than 90 percent of the time, even though the fuel only accounted for about 40 percent of total generation... But the pressure to fill gas storage facilities, backed by the government directives, has forced energy companies to buy — and keep buying — expensive gas, driving the price ever higher... But the urge to buy protection for the winter is driving up prices, and is doing some of the economic damage it was intended to prevent, analysts say.

Martin Sandbu placed the out-sized role of energy prices in inflation in perspective and the limits of pure monetary policy actions in containing inflation,

Suppose energy prices account for 10 per cent of the normal price index. (This is just to make the arithmetics easy. The actual share of energy in the US index is 9.2 per cent, and in the eurozone it is 9.5 per cent.) If they double, the rest of the index has to fall almost 9 per cent. If they triple, other prices have to fall 20 per cent in the aggregate. Central banks have a lot of power, but making most prices fall 20 per cent or more in a year or so may be beyond their ability even if they were determined to try. And considering that most of what we do and produce uses energy, this would require the costs of other inputs into production — in particular, profits and wages — to fall even more significantly. In the context of extreme price rises for some goods, to think today’s high year-on-year inflation rates prove that central banks erred 12 to 18 months ago is to say that central banks should have so firmly arrested the recovery and kept economies so long in recession as to bring about abysmal offsetting negative price changes elsewhere.

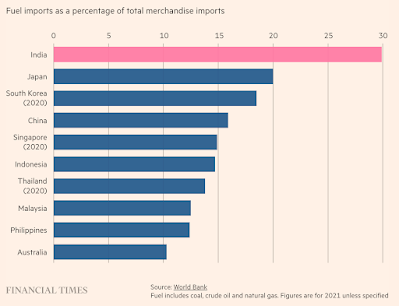

He links to David Sheppard

Sandbu also points to the confluence of factors,

... the bizarre confluence of bad luck: on top of the war and Putin’s energy extortion, we have had weak wind last year, drought-depleted hydropower reservoirs this year, low water transport levels hindering coal barges in Germany, outages in French nuclear plants and fire damage to US gas liquefaction capacity. It is as if it had all been planned to happen at the same time.

See also this on record drought wave sweeping Europe currently, with almost half the continent affected.

If energy prices have risen so much and are driving up inflation, it's difficult to see how monetary policy can be of much help. The supply constraints are unlikely to be significantly eased by any monetary policy tweaks. The highly inelastic nature of energy demand also means that demand response will be muted, howsoever much the price increases.

In the circumstances, the best that can possibly be done would be to cushion the price increases with some form of transfers. European governments have spent about $278 bn since September 2021 to support consumers against high energy prices.

Not just in terms of fiscal support, but in terms of managing the consequences of extreme volatility. Encouraging investment may require ample guarantees if prices hit zero more often than expected. An inevitable quid pro quo will be heavier taxation of energy price windfalls. Throw in the need for greater grid investment and co-ordination between countries and the public and private sector in preparing for a shift to a renewables-based energy system, and the contours of an energy system permanently shaped by politics — and the other way round — become clear.

I think it’s very important [to note] that the function of inflation is not necessarily that obvious. At the end of the day, the definition of inflation is an overall increase in the price level. That gives the impression that all prices are moving at the same time, at the same pace, and the reality is that that never happens. Usually, when you have a low-inflation regime, what you see mostly is relative price changes [some prices going up and others coming down], and these shape production and consumption decisions. These do not give you particular information about the overall pressures of inflation. But if, at some point, you start seeing that more prices are rising and that those rises tend to be more persistent, that means individual price changes carry more information. That starts a process where firms start revising their prices more often, and feeds back into different loops. Cost gets affected, labour markets start responding. And instead of stabilising, high inflation becomes self-reinforcing...

I think a very important sign would be, for example, if the percentage of different goods and services that are producing positive changes suddenly starts decreasing. Because then, you start seeing that the overall component of inflation is coming down, and relative price changes are starting to kick in back again... In your CPI, you can have the analysis to sectors. If you see that 90 per cent of the sectors have positive increase in prices, and now it’s 85 per cent and then it’s 70 per cent, and then you get back to normal, I think that starts giving you signals.

Some thoughts about the current inflationary episode

1. The world economy is entering this episode of inflation with reasonably strong economic fundamentals (corporate and household balance sheets, labour market etc) and strong financial markets. This means that there is considerable run way available to absorb the pain of a recession. This can help keep the recession itself short and shallow.

2. The inflationary signals, while now broad-based, is also primarily supply-shocks induced by the back-to-back triggers of pandemic closures and Ukraine invasion. Besides, energy prices have an out-sized role. It's inevitable that these shocks will dissipate as supply recovers.

The future trajectory of inflation will be critically dependent on whether workers and firms believe that the supply shock will dissipate soon enough without having them to raise wages and prices, thereby triggering a wage-price spiral.

3. In the current inflation episode, the central banks have been behind the curve. But once they realised that inflation was getting baked in, they've responded swiftly, forcefully, and in unison (across developed countries). This means that the intent is being communicated in clear terms. Is this sufficient to convince firms and workers?